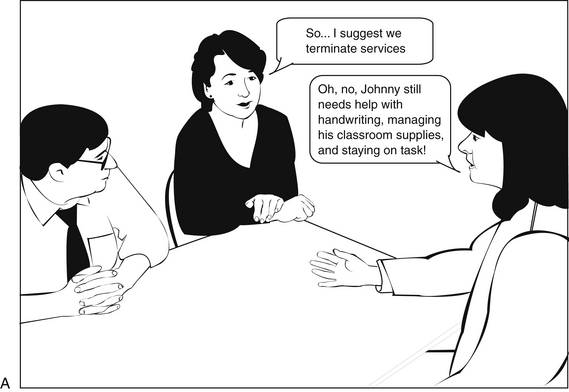

Chapter 13 1 Outline the steps to ethical decision making. 2 Identify the seven ethical principles as outlined in the American Occupational Therapy Association Code of Ethics. 3 Discuss ethical considerations that may occur specific to groups. 4 Describe the ethical principles found in ethical scenarios specific to occupational therapy practice. 5 Outline the resolution and enforcement process for the code of ethics. 6 Understand the importance of following a professional code of ethics. The American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) Code of Ethics is a “statement of principles used to promote and maintain high standards of conduct” in all occupational therapy (OT) practice. It serves as a “guide to professional conduct when ethical issues arise.”4 Inevitably, ethical issues and the need to establish the best outcome to a dilemma arise in practice, because OT practitioners have intimate contact with and a profound influence on the lives of the individuals, groups, and populations they serve. Although each OT practitioner has a personal set of values, he or she represents the profession as a whole when interacting with clients, caregivers, colleagues, authority figures, and subordinates. An understanding of the AOTA Code of Ethics4 is essential for carrying out one’s professional responsibilities. After providing a brief description of ethical theory, the chapter outlines the ethical decision-making process and clearly presents the principles of the AOTA Code of Ethics.4 Providing case scenarios specific to OT practice helps to reinforce the concepts. The chapter concludes with a discussion of the enforcement and resolution process. Morals are the personal values, principles, and beliefs that determine what is right and wrong for the individual.13 Many theories of moral development exist. Freud proposed that the child’s relationship with his or her parents affects moral development. Kohlberg, Piaget, and Gilligan link moral development to cognitive and physical development. They hypothesize that the child moves through stages of value acquisition as he or she develops. Gilligan theorizes that males and females differ in this respect.6 Massey attributes the development of morals to events that take place during childhood and adolescence that result in a group or generation that subscribes to a similar morality.6 Social learning theorists like Bandura view moral behavior as learned through modeling and reinforced by rewards and punishments.9 Ethics are a “system for decision making in the arena of moral values.”6 Both morals and ethics are culture based and influenced by factors such as age, ethnicity and race, religion, gender, gender identification, environment, social milieu, personality, emotional makeup, intelligence, physical health, economic status. The degree of control that an individual perceives himself or herself as having influences the ethical position.10 Ethical theories provide the framework for decision making and help define ways to solve professional dilemmas. These theories can be categorized as follows: Virtue ethics examine the characteristics of the individual and theorize that the individual with certain traits (such as compassion) behave in an appropriate way.8 Divine command ethics postulate that there is a set of rules created by a divine source for directing of moral behavior.13 Teleologic theories hold that an action is ethical or unethical depending on its consequence. In practice, teleologic theories look for a solution to a dilemma that will achieve the best outcome for the most number of people.8 Deontologic theories hold that an action itself is either ethical or unethical with no regard for its consequence. When applied, deontologic theories hold that there is a universal duty to obey rules and follow principles.8 Professional organizations such as AOTA provide its members with guidance in dealing with ethical dilemmas.3,4,13 The establishment and enforcement of the code of ethics ensure maintenance of the standards of the profession. Practitioners rely on professional ethics as opposed to moral beliefs. The ethical decision-making process involves a systematic reasoning structure to enable practitioners to make professional decisions. OT practitioners facing potential ethical dilemmas use a process to guide their analysis and subsequent actions. Purtilo11 lists six steps to assist OT practitioners to arrive at a “caring response” (Box 13-1). The “caring response” includes meeting client needs and performing professional responsibilities. These steps provide a method to thoughtfully act on ethical issues as they arise, staying in agreement with the AOTA Code of Ethics. Some situations cross legal boundaries. Thus, when gathering data and considering alternative courses of action, practitioners examine laws or regulations for practice.8 The OT practitioner should reflect on the outcome using the following questions as guides5,8,11: The AOTA Ethics Commission (EC) informs and educates OT personnel regarding ethical matters and ensures compliance with the ethical standards.2,3 The ethical standards of OT can be found in three documents: Occupational Therapy Code of Ethics4, Guidelines to the Occupational Therapy Code of Ethics2, and Core Values and Attitudes of Occupational Therapy Practice.1 The procedures to enforce the Code of Ethics are described in “Enforcement Procedures for the Occupational Therapy Code of Ethics and Ethics Standards.”3 The Code of Ethics is based on the core values of the OT profession (Box 13-2). Table 13-1 presents the principles of the AOTA Code of Ethics. TABLE 13-1 AOTA, American Occupational Therapy Association. Data from American Occupational Therapy Association (2010) Enforcement procedures for the Occupational Therapy Code of Ethics Standards. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 64(Suppl.), S4-S16 Ethical dilemmas occur when there is a struggle to decide what course of action to take in a difficult situation. The “Occupational Therapy Code of Ethics and Ethics Standard”4 provides standards to guide practitioners in making the right choice to protect the public and the profession. The following scenarios are based on real-life situations that we have encountered and serve to illustrate a range of ethical dilemmas presented in OT practice. OT practitioners rely on knowledge of ethical decision making and the Code of Ethics when deciding the best course of action. Principle 1: “Occupational therapy personnel shall demonstrate a concern for the well-being and safety of the recipients of their services.”4 The term beneficence refers to the act of producing good, as in an act of charity.10 Beneficence is consistent with the OT core value of altruism. AOTA interprets this principle as meaning that OT personnel need to take action to not only provide service that is for the good of their clients but to also protect their clients from harm.4 Working in a service profession such as OT does not automatically make a person altruistic. Being altruistic involves an attitude of doing good for every client. Beneficence requires OT personnel to put the needs of the client above personal needs or the needs of the facility. To carry out this principle, OT personnel must have an understanding of the scope of OT practice and remain competent. Thus, practitioners use current equipment and provide evidence-based intervention. Responses to referral, completion of evaluations, and periodic reassessment should be completed in a timely manner to ensure that the client is receiving the best possible care and that services are terminated when the client is no longer able to benefit from them. The OT practitioner must be able to determine when the client could benefit from the services of another discipline and make necessary referrals. Finally, OT personnel must report behavior that is unethical when it is observed.3,4 Principle 2: “Occupational therapy personnel shall intentionally refrain from actions that cause harm.”4 Nonmaleficence is an “ethical principle of doing no harm.”16 On the surface, this may seem like a simple principle because it seems obvious that an OT practitioner would not want to harm any client. However, there are inherent risks in some aspects of OT intervention that can cause harm regardless of the intent to do good. Before starting treatment, the OT practitioner must identify the risk of the intervention and proceed only if the benefits outweighs the potential risks.11 For example, the practitioner may consider taking a risk with a client to increase his or her independence, or the practitioner may decide to limit the client’s independence because of safety concerns. AOTA outlines circumstances that have the potential to cause harm and cautions OT practitioners to avoid any relationship or activity that could exploit the recipient of services; compromise the therapeutic relationship; or inhibit making clear, objective decisions.2,4 These activities include conflicts of interest, sexual relationships, personal problems, or anything that blurs the boundaries of the relationship between the client and OT practitioner. It is important to understand the differences between a friendship and a therapeutic relationship. Friendships are give-and-take relationships that are beneficial to both parties involved. A therapeutic relationship is intentional and the client is always the focus.14 Having a friendship with a client can cloud judgment and result in a violation of this principle. This concept suggests that practitioners resolve their own personal problems so they are equipped to work with a variety of clients. Personal problems can result in the practitioner being intolerant, mentally unavailable, or treating the client as a sounding board, all of which can be potentially harmful. Nonmaleficence includes the practitioner’s duty to avoid abandoning the client when the OT services can no longer be provided by helping the client transition to appropriate services.4 This may be especially difficult when working with a client who has limited financial or human resources available. The OT practitioner needs to be aware of resources offered in the community and work closely with other disciplines to arrange for the best possible outcome.

Ethical Practice

Ethical Theory

Ethical Decision Making

Aota Code of Ethics—Principles

Principle 1:

Beneficence

Occupational therapy personnel shall demonstrate a concern for the well being and safety of the recipients of their services.

Principle 2:

Nonmaleficence

Occupational therapy personnel shall intentionally refrain from actions that cause harm.

Principle 3:

Autonomy and Confidentiality

Occupational therapy personnel shall respect the right of the individual to self-determination.

Principle 4:

Social Justice

Occupational therapy personnel shall provide services in a fair and equitable manner.

Principle 5:

Procedural Justice

Occupational therapy personnel shall comply with institutional rules; local, state, federal, and international laws; and AOTA documents applicable to the profession of occupational therapy.

Principle 6:

Veracity

Occupational therapy personnel shall provide comprehensive, accurate, and objective information when representing the profession.

Principle 7:

Fidelity

Occupational therapy personnel shall treat colleagues and other professionals with respect, fairness, discretion, and integrity.

Beneficence

Nonmaleficence

Ethical Practice

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access