Levels of Allocating Resources

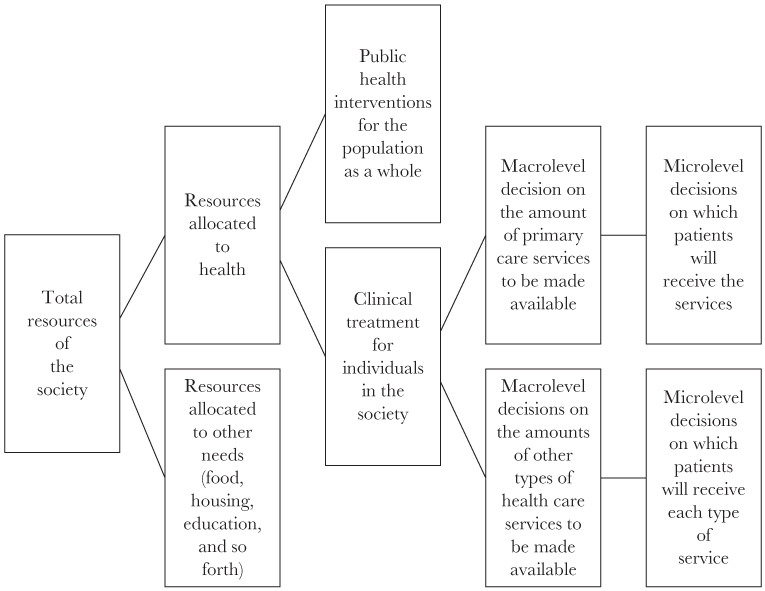

Most discussions about rationing and allocation of health resources focus on specific situations involving denial of care for patients with cancer or other terminal diseases. For example, when people in the United States think about rationing, they might think about a for-profit health maintenance organization (HMO) that refuses to pay for a bone marrow transplant or similar procedure for a patient with cancer, on the ground that the treatment is experimental or “not medically necessary.” Similarly, many people in the United Kingdom are concerned about guidelines for the National Health Service (NHS) that declare certain new drugs for cancer to be not sufficiently “cost effective” for use in the NHS. These types of decisions not to provide or pay for specific drugs or treatments are really part of a much broader set of issues about how to allocate the resources of a society. These broader issues, as set forth in the remainder of the chapter and in Figure 8.1, present a series of decisions that proceed from the most general to the most specific, and these decisions have important ethical implications.

First, a society must decide how much of its resources it wants to devote to health as opposed to other societal needs. Money, personnel, and other resources that are devoted to health will not be available for other needs of the population, such as food, housing, or education, and resources that are devoted to those other purposes will not be available for health (Brock, 2004, p. 201). For example, if current trends in the United States continue, health care spending could use up 35 percent of the nation’s income by 2040, which would severely reduce the money available for other national priorities (Aaron and others, 2005, p. 1).

The second step in this process is to decide on the appropriate balance between public health interventions for the population as a whole and clinical treatment for individuals in the society. For a health system to use its available resources in a cost-effective manner, it needs to give priority to those interventions that have the most effect on population health for each dollar of spending, rather than to interventions that help only individuals and do not make a significant contribution to overall population health (World Health Organization, 2000, p. 52). Allocating resources in ways that best improve population health would be consistent with the utilitarian principle of doing the greatest good for the greatest number, and would also promote the ethical principles of justice and beneficence.

Once a society decides how much of its resources it will devote to the category of treatment for individual patients, the next step is to decide on the amount of each type of care that will be made available. Specific levels of resources can be devoted to primary care, secondary care, and tertiary care, as well as other types of health care services, such as mental health and long-term care. Resources can be allocated to specific types of care by making decisions in the process of government budgeting about the amounts of money that governmental entities will spend to provide various categories of health care facilities and services. In some places, governmental entities also have the authority to control the types of health care facilities and services that are available in the private sector. They can impose regulatory barriers to market entry by passing certificate of need laws, for example. In addition, public and private health insurance systems can allocate their resources to specific types of care by making decisions about covered and noncovered services in the process of insurance plan design.

At this level of decision making, ethical principles of utilitarianism, beneficence, and justice militate in favor of devoting as many resources as possible to primary care services. Primary care has more impact on health than other types of care (Starfield and others, 2005). In addition, primary care is less expensive than other services, because it employs lower technology and workers with less extensive training. So primary care is both more effective and less expensive. Therefore, it is not necessary in this situation to make a trade-off between cost and effectiveness. Moreover, primary care provides more benefit for poor people and residents of rural areas, whereas hospital services are used disproportionately by people who are rich, or at least relatively rich. As the World Health Organization (2000) has recognized, the “distribution of primary care is almost always more beneficial to the poor than hospital care is, justifying the emphasis on the former as the way to reach the worst-off” (p. 16).

Determining the total volume of a health care service that will be made available to the public, by methods such as government budgeting, could be described as a macrolevel decision. After making that macrolevel decision, society can address the microlevel decision of which patients will receive the service. As explained by John Kilner (1984), “Microallocation focuses on determining who gets how much of a particular lifesaving medical resource, once budgetary and other limitations have determined the total amount of the resource available” (p. 18). These microallocation decisions can be made in several different ways, and each of those ways has significant ethical implications.

Methods of Rationing Health Resources

As discussed earlier, it is possible—although not desirable—to ration health care on the basis of ability to pay. That is one of the primary ways in which health care is rationed in the United States, in contrast to the health systems of Europe and other developed countries (Maynard, 1999, p. 6). Although U.S. hospitals have a limited obligation to provide emergency care, and many health care facilities and professionals provide some amount of charity care, inability to pay poses a major barrier to access for millions of people in the United States. More than forty-six million people in the United States are uninsured in the sense that they have no health insurance whatsoever, and many more are severely underinsured. Even people who have health insurance may be unable to pay for necessary care, because their insurance imposes limitations on coverage and requires the patient to pay deductibles and copayments. The system of rationing health care on the basis of ability to pay has been justly criticized on ethical grounds (Persad and others, 2009a). Clearly, it is necessary to find a better way to ration or allocate medical resources.

Another method that has been strongly criticized is rationing care on the basis of the social worth of the individual patient. In the early days of kidney dialysis for end-stage renal disease, anonymous hospital committees chose patients for that life-saving technology by evaluating criteria such as the potential patient’s occupation, education, income, net worth, dependents, and record of public service (Sanders and Dukeminier, 1968, pp. 371–378). Members of those secret committees, individuals such as ministers, lawyers, and bankers, could apply these vague criteria in light of their own values and biases in deciding who would live and who would die. People may have very different views about social worth, and it is clearly inappropriate to permit secret committees to make rationing decisions on the basis of their personal views of the social value of particular individuals. Nevertheless, it may be appropriate in some circumstances to allocate resources to individuals who perform certain functions in society, as a way of promoting the overall good of society. For example, during a pandemic flu, it would be ethical to allocate scarce flu vaccine to public health workers and essential medical personnel, so that they would be able to help other members of society (Persad and others, 2009b, p. 426).

Why not simply ration scarce health care resources to those patients who need them the most or can benefit the most, on the basis of explicit medical criteria? In fact that is the assumption on which many governments rely when they limit available resources and force health care professionals or others to perform the rationing (Aaron and others, 2005, p. 143). In many countries, governments limit their total expenditures for health care services by appropriating a maximum sum of money to provide or pay for care. Those budgetary limitations, such as are found in global budgeting, are not in themselves methods of rationing. However, they create the need for rationing by limiting the available funds, equipment, facilities, and staff. This forces the “budget-holder” to make the difficult rationing decisions (World Health Organization, 2000, p. 58). Governments and their citizens might assume that limited resources are being allocated on the basis of explicit medical criteria. Unfortunately, rationing care on the basis of medical criteria is not straightforward, typically runs into many difficulties, and raises ethical problems in several ways.

First, in some situations, far too many patients will meet the medical criteria for needing particular treatments, such as antiretroviral therapy for HIV/AIDS in Africa, even if the medical criteria are extremely conservative (Rosen and others, 2005, p. 1098). Therefore, medical criteria alone will not solve the problem of deciding who will receive treatment and who will not. Second, medical criteria can be manipulated by health care providers to obtain resources, such as organ transplants, for their patients, even if their patients are not really eligible for those resources (Persad and others, 2009b, p. 427). In the United States, for example, data indicate that some physicians are willing to lie about a patient’s medical condition so that the patient can receive care that the physician considers necessary (Freeman, 1999). Another way in which medical criteria can be abused is by mischaracterizing a patient’s personality, behavior, or social situation as a failure to meet the medical criteria for access to limited resources. For example, patients who lack a stable home or income might be excluded from a list of potential recipients of organ transplants on the “medical” grounds that they have not demonstrated a sufficient likelihood of compliance with posttransplant care or a sufficient network of family or community support. Even without manipulation or mischaracterization, medical criteria do not tell us how to allocate limited resources between people with the same degree of medical need. For example, a young person and an old person might have the same severity of medical need for a transplant. Finally, medical criteria are not purely scientific; they include value judgments. As Persad and others (2009b) have explained, “There are no value-free medical criteria for allocation” (p. 423).

Similarly, rationing care on the basis of first-come, first served, waiting lists, queues, or lotteries would present various ethical complications. These methods of rationing seem to be fair, but in fact they would unfairly benefit certain groups of people (Rosen and others, 2005, p 1102; Persad and others, 2009b, pp. 423–424). For example, people with money, education, and influence would have an unfair advantage in finding out about waiting lists and putting their names on those lists. The use of queues would give an advantage to people who are able to travel to a health care facility and spend long periods of time waiting in line. Lotteries would result in decisions to allocate care on a random basis, without the need to make value judgments among potential recipients. Although that would seem to be fair in the abstract, lotteries could lead to absurd results, such as giving scarce life-saving resources to someone who is already extremely old (Persad and others, 2009b, p. 423). Thus, we might actually prefer to incorporate some value judgments into the process for making allocation decisions, such as including or excluding potential recipients on the basis of age.

Some people have suggested that we should indeed ration care on the basis of age, by denying expensive treatments to patients who already have reached a particular age. In the early part of the 1980s, Great Britain essentially rationed kidney dialysis on the basis of age (Aaron and others, 2005, pp. 36–38). Almost no patients over the age of fifty-five received dialysis in Britain at that time, although dialysis is now provided to patients who are much older. In regard to age, Daniel Callahan has argued that “one fundamental goal of health care and medicine is to help young people become old people, but it is not to have old people become infinitely older” (Sage Crossroads, 2003, p. 4). Therefore Callahan recommended replacing the current “infinity model” of unrestricted obligation with a democratically determined age beyond which expensive treatments would not be provided. Callahan recognized that many people would object to his proposal to ration care on the basis of age, but argued that it is the least bad alternative, because all of the demands for care in society cannot be met. In contrast, Christine Cassell strongly objected to rationing care on the basis of age, because it is impossible to set a particular age for appropriate life expectancy, life expectancy differs for men and women, and patients at a particular age are not uniform in their medical condition or their ability to benefit from additional treatment (Sage Crossroads, 2003, pp. 5–6). Persad and others (2009b) have acknowledged “the public preference for allocating scarce life-saving interventions to younger people,” but have argued that it is inappropriate to sacrifice a young adult in order to save an infant (p. 425).

Most important, both the current public preference to allocate scarce resources to young people and the controversial proposal to restrict allocation for older people are based on value judgments that might be made differently in different countries and cultures. In his research on the Akamba people of Kenya, for example, Kilner (1984) identified several ways in which age-related preferences for rationing scarce health care resources differed from the usual preferences in the United States.

For instance, where only one person can be saved, many Akamba favor saving an old man before a young, even where the young man is first in line. Whereas in the United States we tend to value the young more highly than the old because they are more productive economically, these Akamba espouse a more relational view of life Another Akamba priority documented by the study is: where only one person can be saved, save a man without children rather than one with five A third surprising (by U.S. standards) priority acknowledged by numerous Akamba is the insistence that it is better to give a half-treatment to each of two dying patients—even where experience dictates that a half-treatment is insufficient to save either—than to provide one patient with a full treatment which would almost certainly be lifesaving [Kilner, 1984, p. 19].

Even within Kenya the Akamba are only one group of people among others, and each group may have its own set of preferences for rationing health care resources. The point is not that one set of preferences is preferable or more ethical than another, but rather that any preferences may be limited to a particular culture. Therefore, preferences of any one culture should not be used as a uniform system of rationing in global health or even within a multicultural society.

The following discussion of various ways of rationing scarce antiretroviral therapy (ART) for HIV/AIDS in Africa is excerpted from an article that evaluated explicit and implicit methods of rationing life-saving medical treatment and noted the conflict between social equity and economic efficiency. The article authors concluded that explicit methods of rationing are more likely to maximize the welfare of society and are more likely to promote accountability and transparency in making decisions on public policy.

Excerpt from “Rationing Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV/AIDS in Africa: Choices and Consequences”

By Sydney Rosen and Others

…The message…is clear: rationing of ART is already occurring and will persist for many years to come. The question facing African governments and societies is not whether to ration ART, but how to do so in a way that maximizes social welfare, now and in the future.

Inevitably, the social and economic consequences of rationing a scarce and valuable resource—treatment for a life-threatening illness—will vary widely depending on the rationing system chosen In this paper, we…use an expanded set of criteria to evaluate several rationing systems that already exist in sub-Saharan Africa.

Systems for Rationing

In economic terms, any policy or practice that restricts consumption of a good is a rationing system Non-price rationing of health care has a long history and is widespread and accepted in many parts of the world, reflecting the widely held view that access to health care should be based on some notion of need, and not determined solely by ability to pay. At the same time, non-price rationing is inherently political. It can be, and often is, used to channel resources toward or away from particular groups for reasons unrelated to their absolute or relative need for the resource.

In this paper, we define an ART rationing system as any allocation of public resources that prioritizes access to HIV/AIDS treatment on the basis of any geographic, social, economic, cultural, or other nonmedical factor. This is important, as virtually all programs will set a medical threshold for access to treatment, in most cases having a CD4 count lower than 200 cells/µl or an AIDS-defining illness. A less conservative medical eligibility threshold, such as that of the United States Department of Health and Human Services, which recommends that ART be started at a CD4 count of 350 cells/µl, would dramatically increase the number of eligible patients and intensify the need for rationing. Even with the more conservative eligibility threshold now being applied, however, the figures…indicate that demand for treatment will exceed supply. In the remainder of this paper, we will focus our attention on the nonmedical bases for rationing.

Explicit Rationing Systems

In many cases, governments will set explicit criteria for which types of patients should be eligible for ART first or at lowest cost. The criteria can target selected subpopulations directly, or they can set eligibility requirements that intentionally give some patients better access than others. Possible subpopulations for direct targeting of treatment include:

Mothers of new infants. Rather than face an ever-increasing burden of orphan support, many countries are making ART preferentially available to HIV-positive mothers through testing and treatment at antenatal clinics

Skilled workers. African countries face the loss of vast numbers of educated or trained workers, whose skills are vital to maintaining social welfare, sustaining output, and generating economic growth. Human capital can be conserved by giving treatment priority to nurses, teachers, engineers, judges, police officers, and other skilled workers whose contributions are important to economic development or social stability

Poor people. The social justice agenda pursued by some governments and many nongovernmental organizations argues that the poorest members of society, who are least likely to be able to afford private medical care, should have preferential access to publicly funded treatment programs. Means-testing, which can be applied at the level of the household or the community and calibrated to achieve the desired number of patients, is a common way to ration social benefits.

High-risk populations. The extent to which ART can curb HIV transmission is a subject of current debate in the literature. If treatment reduces the probability of transmission by suppressing viral load, then a public health argument can be made for giving preferential access to high-risk populations, such as commercial sex workers, truck drivers, or intravenous drug users.

Governments can also intentionally create eligibility requirements that result in rationing, without specifying particular target populations. Rationing systems of this type include:

Residents of designated geographic areas. One obvious way to limit access to treatment is to offer it only to those who reside in specified geographic catchment areas. These areas can be distributed around the country, centered in regions of high HIV prevalence, or concentrated in urban centers or politically important regions. Excluding patients who do not live within the designated areas may not be feasible, but most patients will not be able to afford the cost of regular transport or permanent relocation.

Ability to co-pay. If patients are required to contribute even a small share of the cost of treatment, the number who can access therapy is likely to fall dramatically. Governments could in principle match supply and demand by setting and adjusting the level of co-payment required. The obvious outcome is a rationing system that favors the upper socioeconomic tiers of patients, who likely include the majority of skilled workers. In some societies men will also have preferential access when a cash payment is required. A drawback of requiring co-payment is that poorer patients may stop therapy because they run out of funds. This is the reason for stopping cited by nearly half of all non-adherent patients in a recent study in Botswana.

Commitment to adherence to therapy. Adherence to treatment regimens has been found to be the most important determinant of the success of ART at the individual patient level. One way to improve the success of a large-scale treatment program, while at the same time limiting access, could therefore be to restrict therapy to patients who are judged to have the ability and willingness to adhere or who demonstrate high adherence after initiating therapy

Implicit Rationing Systems

The alternative to specifying explicitly who will have priority access to resources is to allow implicit rationing systems to arise. These can be thought of as the default conditions that will prevail in the absence of explicit choices.

Access to HIV testing. Voluntary counseling and HIV testing (VCT) is typically the entry point into an HIV/AIDS treatment program. If some subpopulations, such as youth or particular occupational groups, are targeted for HIV education and VCT services or promotion campaigns, they will have an advantage over others in seeking treatment, as will those who simply live closer to VCT facilities.

Patient costs. Most countries will scale up their treatment programs incrementally, at first offering services at only a few facilities before gradually adding more For most patients, bus or taxi fare will be required for regular trips to the clinic, and each trip will take up a good deal of time. Previous research has found that indirect costs due to travel time and transport play an important role in limiting access to medical care. Unless transport is subsidized, limiting the number of service sites will effectively ration treatment to those who live nearby and to better-off households that have the resources to travel.

First come, first served. In the absence of any other requirements, most facilities are likely to treat everyone who is medically eligible, until the supply of drugs, diagnostics, or expertise runs out. Patients who arrive after that happens may be put on a waiting list, sent to another facility, or simply sent away. This approach, which reflects an absolute shortage of treatment “slots,” is likely to favor three groups of patients: those who are already paying privately for antiretroviral drugs and shift over to publicly funded treatment once it is available; those who develop AIDS-related symptoms first, in most cases because they were infected earliest; and the few HIV-positive individuals who do not yet have AIDS but have taken the initiative to go for a test and know their own status.

Queuing. One of the most common ways to ration scarce resources is the time-honored, time-consuming tradition of queuing. While it is possible to create a waiting list that keeps track of individuals’ places in line, in many African countries the queue is a literal line outside the clinic door. Such queuing will favor patients whose opportunity cost of time is low. This group is likely to be dominated by unemployed men and by women who can bring their small children with them. It may penalize employed persons and farming households that face a high seasonal demand for labor.

No matter what system is used, informal and/or illicit arrangements can often be made that give preferential access to treatment to those with social, economic, or political influence. In all of the implicit systems, and in some of the explicit ones, there will very often be a high degree of queue jumping. Elites capture a disproportionate share of resources in all countries; in developing countries, where enforcement of rules tends to be weak and informal arrangements common, it is safe to assume that members of the elite who are medically eligible for therapy will find a way to get it. De facto rationing on the basis of social or economic position will thus occur. It is the phenomenon of queue jumping that turns what appear to be equitable, if inefficient, rationing systems, such as first-come, first-served, into an inequitable and inefficient approach.

Many other potential criteria for rationing ART have been proposed or are in use. Treatment access could be targeted, for example, to young people (because they respond best to the therapy and have their most productive years ahead of them); families of current patients (to promote adherence); those with debts (so that the loan default rate does not increase); patients with tuberculosis (to suppress transmission of tuberculosis); or children (who are least able to protect themselves).

Evaluating the Systems

The different approaches to rationing ART described above will inevitably have very different social and economic consequences for African populations. In this section, we assess the rationing systems’ probable outcomes using criteria that capture most of the principles that governments use to evaluate policies and social investments. They are by no means the sole criteria of interest, nor should they necessarily be given equal weight. We propose them only as a starting point for thinking about the consequences of alternative approaches.

Effectiveness. Does the rationing system produce a high rate of successfully treated patients?…

Cost savings. Is the cost per patient treated low, compared to other approaches?…

Feasibility. Are the human and infrastructural resources needed for implementation available? We define an approach as feasible if there are no obstacles to carrying it out that appear to be insurmountable under typical conditions in sub-Saharan Africa.

Economic efficiency. To what extent does the system mitigate the long-term impacts of the HIV epidemic on economic development?…

Social equity. Do all medically eligible patients, including those from poor or disadvantaged subpopulations, have equal access to treatment?…

Rationing potential. Will the chosen system sufficiently reduce the number of patients?…

Impact on HIV transmission. To what extent does treatment reduce HIV incidence? Preferentially treating those who are likely to transmit the virus could reduce HIV incidence more than treating those who are not likely transmitters.

Sustainability. Can the system be sustained over time? This criterion pertains to the durability of the source of funding

Effect on the health care system. How does the system for allocating ART affect the country’s health care system as a whole? The choice of rationing strategies could influence whether expanding treatment access will strengthen general health services for poor communities or drain resources from non-HIV health care to meet the demand for ART, further crippling general health services

There are several limitations to the analysis presented…Cost and feasibility are clearly related, for example; at some level of cost, any system could be considered feasible

Conclusions…

Rationing of medical care is not a new phenomenon, nor is it by any means limited to developing countries. Waiting lists, whether for specific procedures, organs for transplant, or experimental treatments, are common in North America and Europe. Many state governments in the US are explicitly limiting access to more expensive AIDS drugs. The HIV/ AIDS crisis in Africa is simply bringing the need for rationing into stark relief.

There is no single rationing system, or combination of systems, that will be optimal for all countries at all times [All systems make a] trade-off between economic efficiency and social equity: rationing systems that rate high in terms of efficiency generally rate low in terms of equity. African societies will place different weights on the values inherent in goals such as equity and efficiency

Because access to antiretroviral drugs is a matter of life or death for patients with AIDS, the choice of rationing systems matters deeply. African governments can take one of two courses: ration deliberately, on the basis of explicit criteria, or allow implicit rationing to prevail. Implicit rationing is not likely to maximize social welfare, nor does it allow for transparency and accountability in policy making. We believe that the magnitude of the intervention now underway and the importance of the resource allocation decisions to be made call for public participation, policy analysis, and political debate in the countries affected. Several proposals have been made for how such processes could be carried out. In the absence of such processes, decisions about access to treatment will be made arbitrarily and will, most likely, result in inequity and inefficiency—the worst of both worlds. Governments that make deliberate choices, in contrast, are more likely to achieve a socially desirable return from the large investments now being made than are those that allow queuing and queue-jumping to dominate. Countries that promote an open policy debate have the opportunity to ration ART in a manner that sustains both economic development and social cohesion—in the age of AIDS, the best of both worlds.

Source: Excerpted from “Rationing Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV/AIDS in Africa: Choices and Consequences,” by Sydney Rosen, Ian Sanne, Alizanne Collier, and Jonathon L. Simon, 2005. PLoS Medicine, 2(11), 1098–1104 (references, tables, and some text omitted). Copyright: 2005 Rosen et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree