5 Ethical Issues in Critical Care

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

• understand the diversity and complexities of ethical issues involving critical care practice

• understand key ethical principles and how to apply them in everyday practice as a critical care registered nurse

• be aware of the availability and access to additional resource material that may inform and support complex ethical decisions in clinical practice

• discuss the ethical implications of the organ donation for transplantation decision-making process

• understand consent and guardianship issues in critical care

• describe the ethical conduct of human research, in particular issues of patient risk, protection and privacy, and how to apply ethical principles within research practice.

Introduction

Nurses are expected to practise in an ethical manner, through the demonstration of a range of ethical competencies articulated by registering bodies and the relevant codes of ethics (see Boxes 5.1 and 5.2). It is important that nurses develop a ‘moral competence’ so that they are able to contribute to discussion and implementation of issues concerning ethics and human rights in the workplace.1 Moral competence and ethical action is the ability to recognise that an ethical issue exists in a given clinical situation, knowing when to take ethical action if and when required, and a personal commitment to achieve moral outcomes.2 This diverse understanding of ethics is paramount to critical care nurses (as part of the critical care team), whose patient cohort is a particularly vulnerable one. Critical care nurses are encouraged to participate in discussion and educational opportunities regarding ethics in order to provide clarity in relation to fulfilment of their moral obligations. The need to support critical care nurses, by mentoring for example, is very important in terms of developing moral knowledge and competence in the critical care context.3

Box 5.1

Australian Nursing and Midwifery Council Code of Ethics for Nurses in Australia, June 200261

Value statements

1. Nurses respect individual’s needs, values, culture and vulnerability in the provision of nursing care.

2. Nurses accept the rights of individuals to make informed choices in relation to their care.

3. Nurses promote and uphold the provision of quality nursing care for all people.

4. Nurses hold in confidence any information obtained in a professional capacity, use professional judgement where there is a need to share information for the therapeutic benefit and safety of a person, and ensure that privacy is safeguarded.

5. Nurses fulfil the accountability and responsibility inherent in their roles.

6. Nurses value environmental ethics and a social, economic and ecologically sustainable environment that promotes health and wellbeing.

Principles, Rights and the Link with Law

The Distinction between Ethics and Morality

Ethics involve principles and rules that guide and justify conduct. Personal ethics may be described as a personal set of moral values that an individual chooses to live by, whereas professional ethics refer to agreed standards and behaviours expected of members of a particular professional group.2 Bioethics is a broad subject that is concerned with the moral issues raised by biological science developments, including clinical practice.

Although some nurses draw a distinction between ethics and morality, there is no philosophical difference between the two terms, and attempting to make a distinction can cause confusion.4 Difficulties arise in ethical decision making where no consensus has developed or where all the alternatives in a given situation have specific drawbacks. These types of situations are referred to as ‘ethical dilemmas’. Dilemmas are different from problems, because problems have potential solutions.5

Ethical Principles

Autonomy

Individuals should be treated as autonomous agents; and individuals with diminished autonomy are entitled to protection. An autonomous person is an individual capable of deliberation and action about personal goals. To respect autonomy is to give weight to autonomous persons’ considered opinions and choices, while refraining from obstructing their actions unless these are clearly detrimental to others or themselves. To show lack of respect for an autonomous agent, or to withhold information necessary to make a considered judgement, when there are no compelling reasons to do so, is to repudiate that person’s judgements. To deny a competent individual autonomy is to treat that person paternalistically. However, some persons are in need of extensive protection, depending on the risk of harm and likely benefit of protecting them, and in these cases paternalism may be considered justifiable.6,7

Nurses are autonomous moral agents, and at times may adopt a personal moral stance that makes participation in certain interventions or procedures morally unacceptable (see the Conscientious objection section later in this chapter).

Beneficence and Non-maleficence

The principle of beneficence requires that nurses act in ways that promote the wellbeing of another person; this incorporates the two actions of doing no harm, and maximising possible benefits while minimising possible harms (non-maleficence).8 It also encompasses acts of kindness that go beyond obligation. In practice this means that although the caregiver’s treatment is aimed to ‘do no harm’, there may be times where to ‘maximise benefits’ for positive health outcomes it is considered ethically justifiable that the patient be exposed to a ‘higher risk of harm’ (albeit ‘minimised’ by the caregiver as much as possible). For example, in the coronary care unit (CCU) a patient may require a central venous catheter (CVC) to optimise fluid and drug therapy, but this is not without its own inherent risks (e.g. infection, pneumothorax on insertion). Evidence-based protocols exist for caregivers/nurses for both the safe insertion of a CVC and subsequent care, so as to minimise possible harms to the patient.

Justice

Justice may be defined as fair, equitable and appropriate treatment in light of what is due or owed to an individual. The fair, equitable and appropriate distribution of health care, determined by justified rules or ‘norms’, is termed distributive justice.6 There are various well-regarded theories of justice. In health care, egalitarian theories generally propose that people be provided with an equal distribution of particular goods or services. However, it is usually recognised that justice does not always require equal sharing of all possible social benefits. In situations where there is not enough of a resource to be equally distributed, often guidelines or policies (e.g. ICU admission policies) may be developed in order to be as fair and equitable as possible.

Conditions of scarcity and competition result in the predominant problems associated with distributive justice. For example, a shortage of intensive care beds may result in critically ill patients having to ‘compete’, in some way, for access to the ICU. Considerable debate exists regarding ICU access/admission criteria, that may vary across institutions. Resource limitations can potentially be seen to negatively affect distributive justice if decisions about access are influenced by economic factors, as distinct from clinical need.9

Ethics and the Law

Ethics are quite distinct from legal law, although these do overlap in important ways. Moral rightness or wrongness may be quite distinct from legal rightness or wrongness, and although ethical decision making will always require consideration of the law, there may be disagreement about the morality of some law. Much ethically-desirable nursing practice, such as confidentiality, respect for persons and consent, is also legally required.4,10

In Australia, there are three broad sources of law. These are:

• Consent to Medical Treatment and Palliative Care Act 1995 (SA);

• Medical Treatment Act 1988 (Vic.);

• Natural Death Act 1988 (NT);

One example of how statute law is applied in practice regards consent for life-sustaining measures; the Consent to Medical Treatment and Palliative Care Act 1995 (SA)11 states that:

It should be noted that each Australian state and territory has differences in its Acts, which can cause confusion. The New Zealand Bill of Rights and the Health Act 1956 are currently under revision in New Zealand.12,13 These documents can be accessed via the New Zealand Ministry of Health (www.hon.govt.nz).

Patients’ Rights

Patients’ rights are a subcategory of human rights. ‘Statements of patients’ rights’ relate to particular moral interests that a person might have in healthcare contexts, and hence require special protection when a person assumes the role of a patient.4 Institutional ‘position statements’ or ‘policies’ are useful to remind patients, laypersons and health professionals that patients do have entitlements and special interests that need to be respected. These statements also emphasise to healthcare professionals that their relationships with patients are constrained ethically and are bound by certain associated duties.4 In addition, the World Federation of Critical Care Nurses has published a Position Statement on the rights of the critically ill patient (see Appendix A3).

Nursing codes of ethics incorporate such an understanding of patient’s rights. For example, codes relevant to nurses have been developed by the Australian Nursing and Midwifery Council (2002)61 and the International Council of Nurses (2002)14 (see Box 5.1). In addition, the Nursing Council of New Zealand has published a Code of Conduct for Nursing that incorporates ethical principles (2004) (Box 5.2).15 These codes outline the generic obligation of nurses to accept the rights of individuals, and to respect individuals’ needs, values, culture and vulnerability in the provision of nursing care. The New Zealand Code particularly notes that nurses need to practise in a manner that is ‘culturally safe’ and that they should practise in compliance with the Treaty of Waitangi. (See Chapter 8 for further details on cultural aspects of care.) Furthermore, the codes acknowledge that nurses accept the rights of individuals to make informed choices about their treatment and care.

Consent

In principle, any procedure that involves intentional contact by a healthcare practitioner with the body of a patient is considered an invasion of the patient’s bodily integrity, and as such requires the patient’s consent. A healthcare practitioner must not assume that a patient provides a valid consent on the basis that the individual has been admitted to a hospital.16 All treating staff (nurses, doctors, allied health etc) are required to facilitate discussions about diagnosis, treatment options and care with the patient, to enable the patient to provide informed consent.17 When specific treatment is to be undertaken by a medical practitioner, the responsibility for obtaining consent rests with the medical practitioner; this responsibility may not be delegated to a nurse.16

Patients have the right, as autonomous individuals, to discuss any concerns or raise questions, at any time, with staff. Hospitals should provide detailed patient admission information, including information regarding ‘patients’ rights and responsibilities’, that usually include a broad explanation of the consent process within that institution. In many countries there is no distinction between the obligation to obtain valid consent from the patient and the overall duty of care that a practitioner has in providing treatment to a patient. Obtaining consent is part of the overall duty of care.11

In recent decades, research in the biomedical sciences has been increasingly located in settings outside of the global north. Much of this research arises out of transnational collaborations made up of sponsors in high income countries (pharmaceutical industries, aid agencies, charitable trusts) and researchers and research subjects in low- to middle-income ones. Research may well be carried out in populations rendered vulnerable because of their low levels of education and literacy, poverty and limited access to health care, and limited research governance. The protections that medical and research ethics offer in these contexts tend to be modelled on a western tradition in which individual informed consent is paramount and are usually phrased in legal and technical requirements. When science travels, so does its ethics. Yet, when cast against a wider backdrop of global health, economic inequalities and cultural diversity, such models often prove limited in effect and inadequate in their scope.2,3 Attempts to address both of these concerns have generated a wide range of ‘capacity-building’ initiatives in bioethics in developing and transitional countries. Organisations such as the Global Forum for Bioethics in Research, the Forum for Ethical Review Committees in the Asia Pacific Region and the World Health Organization have sought to improve oversight of research projects, refine regulation and guidance, address cultural variation, educate the public about research and strengthen ethical review committee structures according to internationally acknowledged ‘benchmarks’.4,5

In order to provide safe patient care, clear internal systems and processes are required within critical care areas, as with any other healthcare service provision. Critical care nurses need to be aware of the relevant policies and procedures to have an understanding of their individual obligations and responsibilities. Primarily, it is the treating medical officer who is legally regarded as the only person able to inform the patient about any material risks associated with a clinical therapy or intervention.18

An understanding of the principle of consent is necessary for nurses practising in critical care. Because of the vulnerable nature of the critically ill individual, direct informed consent is often difficult, and surrogate consent may be the only option, particularly in an emergency. Consent may relate to healthcare treatment, participation in human research and/or use and disclosure of personal health information. Each of these types of consent has differing requirements.19

Consent to treatment

A competent individual has the right to decline or accept healthcare treatment. This right is enshrined in common law in Australia (with state to state differences), and in the Code of Health and Disability Consumers’ Rights in New Zealand (1996).13,20 It is the cornerstone of the legal administration of healthcare treatment. With the introduction in the UK of the Human Rights Act21 there is increasing public awareness of individual rights, and in the medical setting people are encouraged to participate actively in decisions regarding their care. Doctors daily make judgements regarding their patients’ competency to consent to medical investigation and treatment, and in today’s litigious climate they must face the possibility that, from time to time, these decisions will be examined critically in a court of law. Capacity fluctuates with both time and the complexity of the decision being made; thus, sound decisions require careful assessment of individual patients.

Accounts of informed consent in medical ethics claim that it is valuable because it supports individual autonomy yet there are distinct conceptions of individual autonomy, and their ethical importance varies. Consent provides assurance that patients and others are neither deceived nor coerced. Some believe that the present debates about the relative importance of generic and specific consent (particularly in the use of human tissues for research and in secondary studies) do not address this issue squarely, believing that since the point of consent procedures is to limit deception and coercion, they should be designed to give patients and others control over the amount of information they receive and the opportunity to rescind consent already given.22 There is a professional, legal and moral consensus about the clinical duty to obtain informed consent. Patients have cognitive and emotional limitations in understanding clinical information. Such problems pose practical problems for successfully obtaining informed consent. Better communication skills among clinicians and more effective educational resources are required to solve these problems. Social and economic inequalities are important variables in understanding the practical difficulties in obtaining informed consent. Shared decision making within clinical care reveals a pronounced tension between three competing factors: (1) Paternalistic conservatism about disclosure of information to patients has been eroded by moral arguments now largely accepted by the medical profession; (2) While many patients may wish to be given information about available treatment options, many also appear to be cognitively and emotionally ill equipped to understand and retain it; and (3) Even when patients do understand information about potential treatment options, they do not necessarily wish to make such choices themselves, preferring to leave final decisions in the hands of their clinicians.23

Consent is considered valid when the following criteria are fulfilled; consent must:

• be informed (the patient must understand the broad nature and effects of the proposed intervention and the material risks it entails)

• encompass the act to be performed

For incompetent individuals, the situation is less clear and varies between jurisdictions.

To be competent, an individual must:

• be able to comprehend and retain information

• believe it (i.e. they must not be impervious to reason, divorced from reality or incapable of judgement after reflection)

• be able to weigh that information up (i.e. consider the effects of having or not having the treatment)

In an emergency, healthcare treatment may be provided without the consent of any person, although ‘emergency’ has not routinely been formally defined. It should also be noted that nurses must seek consent for all procedures that involve ‘doing something’ to a patient (e.g. administering an injection), and should be wary of relying on ‘implied’ consent. Seeking consent in this type of everyday situation is less formal than obtaining consent for a surgical intervention, although it still represents ethically (and legally) prudent practice. Consent should never be implied, despite the fact that the patient is in a critical care area.17 Obtaining consent generally involves explaining the procedure and seeking affirmation from the patient (or guardian/family), ensuring that there is understanding and agreement to the treatment. This principle is clearly articulated by the General Medical Council in the UK with the following statement:

Successful relationships between doctors and patients depend on trust. To establish that trust you must respect patients’ autonomy – their right to decide whether or not to undergo any medical intervention … [They] must be given sufficient information, in a way that they can understand, in order to enable them to make informed decisions about their care.24

In many countries, if patients believe that clinicians have abused their right to make informed choices about their care, they can pursue a remedy in the civil courts for having been deliberately touched without their consent (battery) or for having received insufficient information about risks (negligence). To avoid the accusation of battery, clinicians need to make clear what they are proposing to do and why ‘in broad terms’. With respect to negligence, the amount of information about risks required is that deemed by the court to be ‘reasonable’ in light of the choices that patients confront.25

If a person is assessed as not being competent, consent must be sought from someone who has lawful authority to consent on his or her behalf. If the courts have appointed a person to be a guardian for an incompetent individual, then the guardian can provide consent on behalf of that individual. However, even for formally-appointed guardians, certain procedures are not allowed and the consent of a guardianship authority is required. If there is no guardianship order then, strictly speaking, consents for healthcare treatment may be given only by the guardianship authority. Some states have legislated to allow this authority to be delegated to a ‘person responsible’ or ‘statutory health authority’ without prior formal appointment. This person would usually be a spouse, close relative or unpaid carer of the incompetent individual. As with formally appointed guardians, the powers of a ‘person responsible’ are limited by statute.19

Consent to research involving humans

Consent in human research is guided by a variety of different documents. In Australia this predominantly includes the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) and the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (2007);8 while in New Zealand it is by the Health Research Council of New Zealand (HRCNZ), Guidelines on Ethics in Health Research and the HRCNZ Operational Standard for Ethics Committee (OS).26,27 In the UK guidance is provided by the General Medical Council.24 In the US there are required elements of written Institutional Review Board (IRB) procedures under Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) regulations for the protection of human subjects and relevant Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) Department of Health and Human Services ‘guidance’ regarding each required element.

Although the specific detail varies between organisations and jurisdictions, in general ‘consent to medical research documentation’ should include the following:19

• A statement that the study involves research

• An explanation of the purposes of the research

• The expected duration of the subject’s participation

• A description of the procedures to be followed

• Identification of any procedures which are experimental

• A description of any reasonably foreseeable risks or discomforts to the subject

• A description of any benefits to the subject or to others which may reasonably be expected from the research

• A disclosure of appropriate alternative procedures or courses of treatment, if any, that might be advantageous to the subject

• A statement describing the extent, if any, to which confidentiality of records identifying the subject will be maintained

• For research involving more than minimal risk, an explanation as to whether any compensation, and an explanation as to whether any medical treatments are available, if injury occurs and, if so, what they consist of, or where further information may be obtained.

• An explanation of whom to contact for answers to pertinent questions about the research and research subjects’ rights, and whom to contact in the event of a research-related injury to the subject

• A statement that participation is voluntary, refusal to participate will involve no penalty or loss of benefits to which the subject is otherwise entitled, and the subject may discontinue participation at any time without penalty or loss of benefits, to which the subject is otherwise entitled.

Consent to conduct research involving unconscious individuals (incompetent adults) in critical care is one of the situations not comprehensively covered in most legislation (see also Ethics in research later in this chapter).

Application of Ethical Principles in the Care of the Critically Ill

Critical care nurses should maintain awareness of the ethical principles that apply to their clinical practice. The integration of ethical principles in everyday work practice requires concordance with care delivery and ethical principles. There is a risk that nurses may become socialised into a prevailing culture and associated thought processes, such as the particular work group on their shift, the unit where they are based, or the institution in which they are employed. Depending on the prevalent culture at any one of these levels, nursing practice may be highly ethical or less ethically justifiable. The ‘group think’ approach of ‘That’s how we’ve always done it’ requires critical reflection on what is the ethical or ‘right thing to do’.28 Clinical audits and other dedicated review systems and processes are useful platforms for ethical discussion and debate between critical care colleagues.

End-of-Life Decision Making

With advances in technology in health care, it is possible more than ever before to restore, sustain and prolong life with the use of complex technology and associated therapies, such as mechanical ventilation, extracorporeal oxygenation, intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation devices, haemodialysis and organ transplantation. In addition, new medication treatment options contribute significant promises of added benefits, and fewer side effects, and are heralded by drug companies and journals across the world. Combinations of these therapies in critical care units are part of everyday management of critically ill patients. While technology is capable of maintaining some of the vital functions of the body, it may be less able to provide a cure. Managing the critically ill patient in many cases represents a provision of supportive, rather than curative, therapies.29

A common ethical dilemma found in critical care is related to the opposing positions of ‘maintaining life at all costs’ and ‘relieving suffering associated with prolonging life ineffectively’. Patients that would probably have previously died can now be maintained for prolonged periods on life support systems, even if there is little or no chance of regaining a reasonable quality of life. Assessment of their ‘post-critical illness’ quality of life is complex, emotive and forms the basis of significant debate, compounded by the nuances of each individual patient’s case. Hence, decisions regarding withdrawal and withholding of life support treatment(s) are not made without substantial consideration by the critical care team.30

Withdrawing/Withholding Treatment

The incidence of withholding and withdrawal of life support from critically ill patients has increased to the extent that these practices now precede over half the deaths in many ICUs,31 although the incidence in other critical care areas has not been reported. Although there is a legal and moral presumption in favour of preserving life, avoiding death should not always be the pre-eminent goal.32 The withholding or withdrawal of life support is considered ethically acceptable and clinically desirable if it reduces unnecessary patient suffering in patients whose prognosis is considered hopeless (often referred to as ‘futile’) and if it complies with the patient’s previously stated preferences. Life support includes the provision of any or all of ventilatory support, inotropic support for the cardiovascular system and haemodialysis, to critically ill patients. Withholding/withdrawal of life support are processes by which healthcare therapy or interventions either are not given or are forgone, with the understanding that the patient will most probably die from the underlying disease.33

In Australia, when active treatment is withdrawn or withheld, legally the same principles apply. The Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society (ANZICS) recommends an ‘alternative care plan’ (comfort care) be implemented with a focus on dignity and comfort. All discussions should be recorded in the medical records including the basis for the decision, who has been involved and the specifics of treatment(s) being withheld or withdrawn.34 There are marked differences in the ‘foregoing of life-sustaining treatments’ that occur between countries and in the patient level of care variation even within the same country. What may be adopted legally and ethically or morally in one country may not be acceptable in another. The withholding and withdrawing of therapies is considered passive euthanasia and is legal and accepted practice in terminally-ill ICU patients in most of Europe, however in parts of Europe, life-sustaining treatments are withheld but not withdrawn as the withdrawal of therapies leading to death is considered illegal and unethical. In the Netherlands and Belgium, active life ending procedures are permitted and performed with the specific intent of causing or hastening a patient’s death. In the US35–37 and Europe38 the majority of doctors have withheld or withdrawn life-sustaining treatments.

The majority of the community and doctors favour active life-ending procedures for terminally-ill patients.39,40 In the Ethicatt study, questionnaires on end of life decision-making were given to 1899 doctors, nurses, patients who were in ICUs and family members of the patients in six European countries. Less than 10% of doctors and nurses would like their life prolonged by all available means, compared to 40% of patients and 32% of families. When asked where they would rather be if they had a terminal illness with only a short time to live, more doctors and nurses preferred being home or in a hospice and more patients and families preferred being in an ICU. Differences in responses were based on respondent’s country.39,40

Diverse cultural, religious, philosophical, legal and professional attitudes lead to great difference in attitudes and practices. Observational studies demonstrate that North American health care workers consult families more often than do European workers,39,41 and some seriously ill patients wish to participate in end of life decisions whilst others do not.42

In most cases where there is doubt about the efficacy and appropriateness of a life-sustaining treatment, it may be considered preferable to commence treatment, with an option to review and cease treatment in particular circumstances after broad consultation. Inconsistency exists in decision making about when and how to withdraw life-sustaining treatment, and the level of communication among staff and family.9 Documented guidelines for cessation of treatment are not necessarily common in clinical practice, with disparate opinion a recognised concern in some cases. Dilemmas arise when there are disparate views within the team as to what constitutes ‘futility’ and with associated decisions regarding the next step or steps when a patient’s outlook is at its most grave. In a UK study that attempted to draft cessation of treatment guidelines, nursing staff were concerned over legality, morality, ethics and their own professional accountability. Medical decisions to withdraw treatment were shown to vary between medical staff and among patients with similar pathologies.43

Because ethical positions are fundamentally based on an individual’s own beliefs and ethical perspective, it may be difficult to gain a consensus view on a complex clinical situation, such as withdrawal of treatment. While it is essential that all members of the critical care team be able to contribute and be heard, the final decision (and ultimately legal accountability in Australia and New Zealand for the act of withdrawal of therapy) rests with the treating medical officer. However, the decision-making process certainly must involve broad, detailed and documented consultation with family and team members. If there is stated objection from a family member, especially if the person has medical power of attorney (or equivalent), the doctor must take this into consideration and respect the rights of any patient’s legal representative. In that event, it is likely that withdrawal of treatment will not occur until concordance is reached. (This is different in the case of a person who is legally declared brain dead; see Brain death section.)34

In the Ethicus study of 4248 patients who died or had limitations of treatments in 37 ICUs in 17 European countries, life support was limited in 73% of patients. Both withholding and withdrawing of life support was practised by the majority of European intensivists while active life ending procedures despite occurring in a few cases remained rare.38 The ethics of withdrawal of treatment are discussed in detail in the ANZICS Statement on Withholding and Withdrawing Treatment.34 The NHMRC publication entitled Organ and Tissue Donation, After Death, for Transplantation: Guidelines for Ethical Practice for Health Professionals provides further discussion of the ethics of organ and tissue donation.44

Decision-Making Principles

End-of-life decision making is usually very difficult and traumatic. Because of this difficulty, there is sometimes a lack of consistency and objectivity in the initiation, continuation and withdrawal of life-supporting treatment in a critical care setting.30 Traditionally, a paternalistic approach to decision making has dominated, but this stance continues to be challenged as greater recognition is given to the personal autonomy of individual patients.9

Decision making in the critical care setting is conducted within, and is shaped by, a particular sociological context. In any given decision-making situation, the participants hold different presumptions about their roles in the process, different frames of reference based on different levels of knowledge, and different amounts of relevant experience.45 Nurses, for example, may conform to the dominant culture in order to create opportunities to participate in decision making, and thereby may conform to the values and norms of medicine. Although the nursing role in critical care is pivotal to implementing clinical decisions, it is sometimes unacknowledged and devalued. Nurses appear at times unable to influence the decision-making process.46

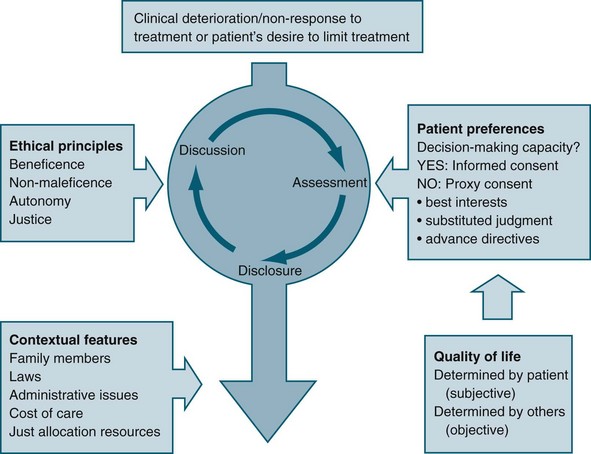

Some international literature reflects the different ethical reasoning and decision-making frameworks extant between medical staff and nurses. In general, nurses focus on aspects such as patient dignity, comfort and respect for patients’ wishes, while medical staff tend to focus on patients’ rights, justice and quality of life.47 Involvement of the patient (where possible) and family in decision making is an important aspect of matching the care provided with preferences, expectations, values and circumstances (see Figure 5.1).48

Quality of Life

Despite the importance placed on quality of life in terms of its influence in the decision-making process, it is difficult to articulate a common understanding of the concept. Quality of life is often used as a means of justifying a particular decision about treatment that results in either cessation of life or continued life-sustaining treatment, and it tends to be expressed as if a shared understanding exists.4

Often, quality of life is considered to consist of both subjective and objective components, based on the understanding that a person’s wellbeing is partly related to both aspects; therefore, in any overall account of the quality of life of a person, consideration is given to both independent needs and personal preferences.9 Subjective components refer to the experience of personal satisfaction or happiness, or the attainment of personal informed desires or preferences. Conversely, objective components refer to factors outside the individual, and tend to focus on the notion of ‘need’ rather than desires (e.g. the level to which basic needs are met, such as avoiding harm, and adequate nutrition and shelter).

Best Interests Principle

The best interests principle relies on the decision makers possessing and articulating an understanding or account of quality of life that is relevant to the patient in question, particularly in making end-of-life decisions. Although assumptions are commonly made that a shared understanding of the concept of quality of life exists, it may be that the patient’s perspective on what gives his or her life meaning is quite different from that of other people. In addition, individual preferences may change over time. For example, John may have stated in the past that he would never want to live should he be confined to a wheelchair; however, after an accident has rendered him a quadriplegic his preference may well be different. Ethical justification of the best interests principle therefore requires a relevant and current understanding of what quality of life means to the particular patient of concern.49

Patient Advocacy

Enduring guardians can potentially make a wider range of decisions than a medical agent, but an enduring guardian can make decisions only once a person is considered to be unable to make his/her own decisions. Acts such as the Consent to Medical Treatment and Palliative Care Act 1995 (SA) exist to facilitate choice in healthcare treatment that individuals may wish to have or refuse when they are unable to make their wishes known because of an illness.11

Substituted Judgement Principle

A substituted judgement is where an ‘appropriate surrogate attempts to determine what the patient would have wanted in his/her present circumstances’.50 The person making the decision should therefore attempt to utilise the values and preferences of the patient, implying that the proxy decision maker would need an in-depth knowledge of the patient’s values to do so. Making a substituted judgement is relatively informal, in the sense that the patient usually has not formally appointed the proxy decision maker. Rather, the role of proxy tends to be assumed on the basis of an existing relationship between proxy and patient. Difficulties related to this principle include that making an accurate substituted judgement is very difficult, and that the proxy might not be the most appropriate person to have taken on the role.51

Advance Directives

For individuals wanting to document their preferences regarding future healthcare decisions with the onset of incompetence, there are ‘anticipatory direction’ and ‘advance directive’ forms available. Advance directives can be signed only by a competent person (before the onset of incompetence), and can be either instructional (e.g. a living will) or proxy (the appointment of a person(s) with enduring power of attorney to act as surrogate decision maker), or some combination of both. Advance directives can therefore inform health professionals how decisions are to be made, in addition to who is to make them. New Zealand and most states of Australia have an Act that allows for the appointment of a person to hold enduring power of attorney.52 It is found in the literature that most individuals do not want to write advanced directives and are hesitant to document their end of life care desires. Advance directives were created in response to increasing medical technology.53,54

An advance health care directive, also known as a living will, personal directive, advance directive or advance decision, are instructions given by individuals specifying what actions should be taken for their health in the event that they are no longer able to make decisions due to illness or incapacity, and appoints a person to make such decisions on their behalf. A living will is one form of advance directive, leaving instructions for treatment. Another form authorises a specific type of power of attorney or health care proxy, where someone is appointed by the individual to make decisions on their behalf when they are incapacitated. People may also have a combination of both. One example of a combination document is the Five Wishes advance directive in the US, created by the non-profit organisation Aging with Dignity.55 Although not legal documents, ‘good palliative care plans’ are used in some jurisdictions as a record of a discussion between the patient, family members and a doctor about palliative care or active treatment. These are useful records to provide clarity when treatment options require full and frank discussion and consideration, particularly regarding complex, critically ill patients (see Palliative care below).

Medical Futility

The concept of futility may be used by critical care doctors and nurses as a rationale for why treatment, including life-saving or sustaining treatment, is not considered to be in the patient’s best interests. At times, the concept of futility may be used inappropriately, and therefore unethically, for example if used to coerce relatives into agreeing to cease the patient’s treatment.56

Futility is a concept that has widespread use in healthcare ethics guidelines for the cessation of treatment, particularly with reference to ‘do-not-resuscitate’ orders and the withdrawal of lifesaving or sustaining treatment. Treatment is considered futile if it merely preserves permanent unconsciousness or cannot end dependence on intensive health care.50 Futility is used to cover both cases of predicted impossibility of the success of treatment (‘physiological’ futility) and cases in which there are competing interpretations of probabilities and value judgements, such as a balance of probable benefits and burdens.6

Physiological futility is also commonly defined as ‘useless treatment’; when clinicians conclude (through personal experience, experience shared with colleagues, or consideration of reported empirical data) that in the past 100 cases a healthcare treatment has had no desired effect.57 This particular definition is purported to defend against doctors being pressured into pursuing extreme and absurd interventions as a result of not being able to claim categorically that a particular treatment will be useless. The proposal is justified by appealing to the commonly used statistical evaluation employed in clinical trials (P = 0.01). A physiologically futile treatment may be, for example, cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the setting where the patient has a ruptured left ventricle.

There is no definition of futility in Australasian legislation, although there is limited guidance within some Acts. An example is provided by the South Australian legislation referred to earlier11:

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree