CHAPTER 10

Essential Forces and Factors in Labor

1 List the forces affecting labor.

2 Identify the possible causes of the onset of labor.

3 Discuss the oxytocin release theory of labor onset.

4 Discuss the fetal prostaglandin theory of labor onset.

5 Describe the amount of uterine activity required to effect cervical changes.

6 Differentiate between muscle contraction and muscle retraction, and discuss the significance of both to the progress of labor.

7 List the techniques used for assessing uterine activity and uterine efficiency.

8 Differentiate between true labor and false labor, using information gathered by history and physical examination.

9 Identify the basic pelvic shapes.

10 Recognize adequate pelvic dimensions.

11 Describe methods for assessing pelvic capacity.

12 Compare and contrast the anticipated progress of labor for each of the four pelvic shapes.

13 Identify and discuss maternal conditions that may alter or influence pelvic capacity.

14 Analyze the relation between maternal posture and the pelvic passage.

15 Define fetal lie, attitude, presentation, presenting part, position, and station.

16 List the mechanisms of spontaneous vaginal delivery.

17 Discuss the significance of breech presentation or transverse lie to the progress of labor.

18 Recognize fetal variables that may interfere with the progress of labor.

19 Discuss the significance of fetal malpositioning to the course and outcome of labor.

20 Describe the characteristic emotions associated with labor.

21 Identify variables that determine a couple’s expectations for the labor and birth experience.

22 Distinguish between adaptive coping and maladaptive coping during labor.

23 Describe the nursing actions that maximize the forces of labor.

24 Predict when a woman is at risk for a difficult labor as the result of an alteration in one of the forces of labor.

INTRODUCTION

Traditionally, four essential forces or powers have been identified as the determinants of labor outcome (Biancuzzo, 1993). These “4 P’s,” which are interrelated, are:

1. Power: The uterine muscle provides the power of labor, and the onset and establishment of a satisfactory contraction pattern is a readily recognized force of labor.

2. Passage: The bony boundaries of the pelvis define the labor passage, and its shape and configuration determine the ease with which the infant is expelled from the uterus.

3. Passenger: The infant, or passenger, is an active participant in the labor process as it moves and turns to accommodate to the maternal pelvis.

4. Psyche: A woman’s psyche, or emotional system, determines her total response to labor and influences physiologic and psychologic functioning.

CLINICAL PRACTICE

(a) The uterus is stretched to threshold point, leading to synthesis and release of prostaglandin.

(b) The pressure on the cervix and its nerve plexus reaches threshold point.

(c) Oxytocin stimulation theory (Gay, 1978)

[i] Exogenous oxytocin is known to stimulate myometrial contractions, but no evidence clearly documents its role in the onset of labor.

[ii] Progesterone inhibits myometrial response throughout pregnancy.

[iii] Estrogen at term enhances myometrial sensitivity to oxytocin.

[iv] A surge of oxytocin may be released by stretching of the cervix at term (Ferguson’s reflex), but studies do not agree about this possibility.

(d) Progesterone withdrawal theory

[i] In animals, a decrease in progesterone is followed by evacuation of the uterus.

[ii] In humans, no firm evidence documents that progesterone is decreased at term.

[iii] Many researchers, however, support the view that an altered progesterone-estrogen ratio leads to increased myometrial contractility.

(a) Placental aging and deterioration trigger initiation of contractions.

(b) Fetal cortisol theory (Gay, 1978)

[i] It is reasoned that normal fetal adrenal glands produce a steroid, cortisol, which stimulates the onset of labor

[ii] It is recognized that anencephaly causes adrenal dysfunction secondary to pituitary dysfunction

[iii] Empirically, anencephalic fetuses tend to have prolonged gestations

(c) Prostaglandin synthesis theory (Gay, 1978)

[i] Prostaglandins are known to stimulate uterine contractions at any gestational age

[ii] Prostaglandin is present in increased quantities in blood and amniotic fluid during labor

[iii] Prostaglandin production requires the precursor arachidonic acid

[iv] Esterified arachidonic acid is stored in fetal membranes

[v] It is postulated that free arachidonic acid is released at term and is then converted by agents in the uterine decidua to prostaglandin

b. Physiology of contractions (Cunningham et al, 2005)

(a) Uterine muscle is controlled by involuntary innervation.

(b) Alpha-receptors stimulate uterine contractions.

(c) Beta-receptors stimulate uterine relaxation.

(d) Norepinephrine and epinephrine stimulate alpha- and beta-receptors.

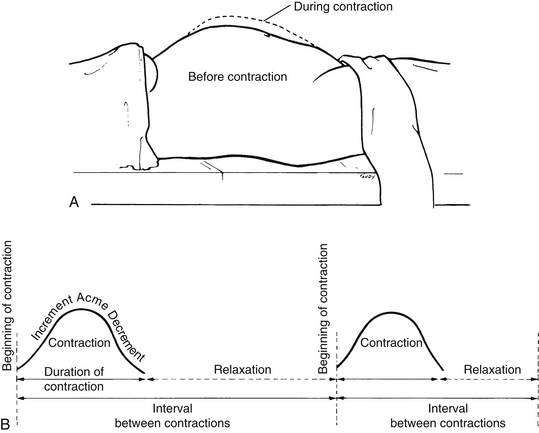

(2) Contraction: the shortening of a muscle in response to a stimulus, with return to its original length (Figure 10-1)

(3) Retraction: the shortening of a muscle in response to a stimulus, without return to its original length; muscle becomes fixed at a relatively shorter length, but no increase in baseline tension occurs after the contraction (also known as brachystasis)

(a) With each uterine contraction, the upper segment of the uterus becomes shorter and thicker, and the lower segment of the uterus becomes longer, thinner, and more distended

(b) The division between the contractile upper segment of the uterus and the passive lower uterine segment is the physiologic retraction ring.

(c) Longitudinal traction on the cervix by the upper portion of the uterus as it contracts and retracts leads to cervical effacement and dilation.

(d) The shortening and thickening of the upper uterine segment lead to fetal descent.

(4) Tonus: the degree of pressure exerted by the uterine musculature as measured by intrauterine pressure

(a) Tonus is measured in millimeters of mercury (mm Hg), which is also called torr.

(b) Normal baseline tonus between contractions is 8 to 12 mm Hg.

(c) Pressure at peak of a contraction ranges from 35 to 75 mm Hg.

(5) Intensity: the rise in intrauterine pressure above baseline brought about by a contraction

(a) Intensity is measured as the difference between peak pressure and baseline pressure.

(b) Normally, 30 to 50 mm Hg intensity is necessary for effective labor.

(6) Pacemaker: the site of electrical activity responsible for triggering a uterine contraction

(a) Pacemakers are generally located in the fundus of the uterus (fundal dominance).

[i] Previously thought that specialized cells existed that acted as pacemakers

[ii] Current thinking is that the cells responsible for initiating electrical stimuli are not different from surrounding myometrial cells.

[iii] Fundal dominance occurs because the fundus contains a greater number of myometrial cells than other areas of the uterus

(b) The wave of the contraction begins in the fundus then proceeds downward to the rest of the uterus (descending gradient).

[i] The duration of the contraction diminishes progressively as the wave moves away from the fundus; therefore, during any contraction, the upper portion of the uterus is contracted for a longer time.

[ii] The intensity of the contraction diminishes from top to bottom, so that the upper segment contracts more strongly than the lower segment.

[iii] If the duration and intensity of the contraction were constant throughout, effacement and dilation could not occur.

(c) Asymmetry results when the uterine halves function independently, leading to ineffective contractions with minimal dilation.

(d) Ectopic pacemakers (i.e., pacemakers located outside the uterine fundus) result in spasmodic myometrial contractions, which are disorganized and colicky, and rarely effective in producing dilation (see Chapter 11 for a complete discussion of dysfunctional labor).

(1) Discomfort is perceived, but cervical changes do not occur.

(2) Discomfort is usually perceived more in lower abdomen than in back.

(3) Discomfort may be caused by uterine contractions, intestinal or bladder spasm, or abdominal wall muscle tension.

(4) Despite perceived discomfort, the uterus is often relaxed, although mild contractions may be palpated.

(5) Contractions are irregular and short in duration.

(6) The interval between contractions is long and irregular, and it does not decrease as discomfort continues.

(7) The intensity does not increase with time.

(8) Contractions are easily interrupted by medication and activity, such as walking.

(9) There is an absence of cervical bloody show.

(10) False labor is mentally and physically tiring for the patient.

(1) By definition, true labor is the onset of contractions that leads to progressive cervical effacement and dilation.

(2) Discomfort is perceived in both front and back.

(3) Hardening of the uterus is palpable.

(4) Contractions occur at regular intervals, usually beginning 20 to 30 minutes apart, lasting 10 to 20 seconds, and of mild intensity.

(5) Frequency, duration, and intensity increase as contractions continue.

(6) Medication does not easily disrupt true labor.

(7) Walking increases the intensity.

(9) Bulging of the membranes may occur.

(a) Myometrial activity is solely responsible for effacement and dilation of the first stage of labor.

(b) Uterine contractions create increased intrauterine pressure, which exerts tension on cervix and pressure on the descending fetus.

(c) Myometrial effectiveness is improved by good uterine blood flow.

(a) During the second stage of labor, involuntary and voluntary forces are present.

(b) Involuntary myometrial activity continues to create increased intrauterine pressure, which exerts pressure against the fetus.

(c) Full dilation causes involuntary reflex desire to bear down, which increases intraabdominal pressure, thereby increasing intrauterine pressure (Roberts, Goldstein, Gruener, Maggio, & Mendez-Bauer, 1987).

(d) Voluntary efforts to bear down increase intraabdominal pressure, thereby increasing intrauterine pressure.

(e) Positions that flex the legs on the abdomen increase intraabdominal pressure, thereby increasing intrauterine pressure.

(1) Contraction frequency is measured from the beginning of one contraction to the beginning of the next contraction.

(2) Typical frequency of contractions during active labor is two to five contractions per 10 minutes.

3. Diagnostic studies and techniques

a. Manual palpation of contractions

b. External monitoring of contractions: tocotransducer

(1) The tocotransducer reflects increased intraabdominal pressure.

(2) Placement of the tocotransducer influences the accuracy of information.

(3) Intraabdominal pressure does not directly correlate with intrauterine pressure; therefore, it does not measure the actual intensity of contractions.

(4) No known risks have been found of using the tocotransducer, but some women feel confined and uncomfortable.

c. Internal monitoring of contractions: intrauterine pressure catheter

(1) Allows direct measurement of intrauterine pressure

(2) Provides accurate measurement of actual intensity of uterine contraction

(a) Introduction of infection into uterine cavity

(b) Uterine rupture caused by traumatic insertion (see Chapter 12 for complete discussion of contraction monitoring)

a. Musculoskeletal deformities and diseases

(1) A contracted pelvis may lead to disproportion between the pelvis and the fetus.

(2) Uterine neoplasms (e.g., fibromyomas, ovarian cysts) may block the birth canal, impeding the passage.

(a) May lead to abortion, premature labor, or premature rupture of membranes

(b) Has been implicated in incompetent cervix

(c) May be causative factor of breech or transverse lie

(d) Vaginal delivery is possible but may be accompanied by uterine inertia or obstruction of descent.

(a) Defined as a height of less than 1473 cm (4 feet, 10 inches) at maturity

(b) Pelvic dimensions may be favorable if dwarfism is proportionate.

(a) If the thoracic area is involved, little or no reduction of pelvic capacity occurs.

(b) If the dorsolumbar or lumbosacral area is involved, marked pelvic deformity is common.

(6) Bony disease of femurs or acetabula may result in abnormal pressures on the pelvis during development, leading to pelvic asymmetry and reduced pelvic capacity.

(7) Nutritional deficiencies and diseases (e.g., rickets) may contribute to bony deformities of the pelvic passage.

b. Pelvic trauma or injury may lead to asymmetry and reduced capacity.

(1) Includes accidental insults as well as those resulting from surgical procedures (e.g., dilation and curettage [D&C], cone biopsy, uterine aspiration)

(2) May result in loss of cervical integrity with resultant incompetence

(3) May result in cervical scarring and adhesions, with resultant failure to dilate

(4) Cervical abnormalities are frequently found among women exposed in utero to diethylstilbestrol (DES).

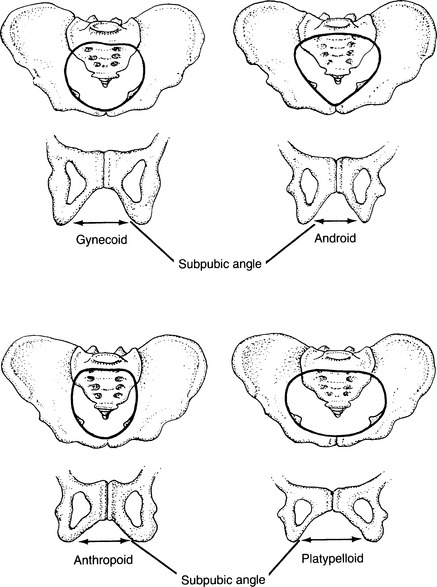

a. Pelvic shapes (Figure 10-2) (Cunningham et al, 2005)

(1) Rigid classification is not possible.

(a) Name assigned is based on classification of inlet.

(b) Nonconforming characteristics are then described.

(c) Shape and size of pelvis influence fetal position and attitude.

(b) Early and complete internal rotation occurs.

(d) This shape offers the optimal diameters in all three planes of the pelvis.

(a) Posterior segments are reduced in all the pelvic planes.

(b) Deep transverse arrest is common.

(c) Failure of rotation is common.

(e) Approximate incidence is 20%, but it occurs more frequently among white women (30%) than nonwhite women (15%).

(a) Reduced transverse measurements are compensated by large anteroposterior diameters.

(b) Prognosis is generally more favorable than android or platypelloid.

(c) This shape may deliver occiput posterior.

(d) Approximate incidence is 25%, but it occurs more frequently among nonwhite women (50%) than white women (25%).

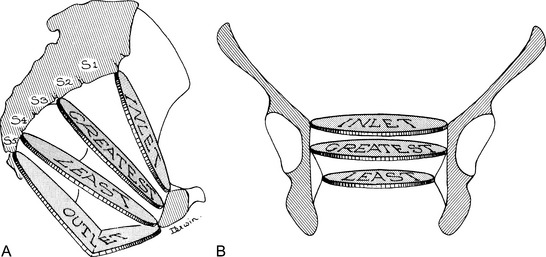

(1) The measurements that define the obstetric capacity of the pelvis

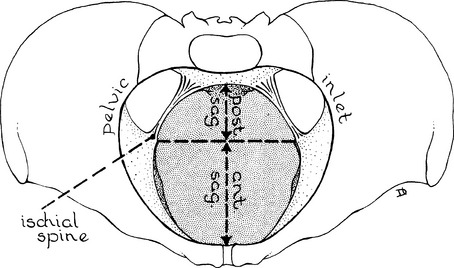

(a) Obstetric conjugate of the inlet (Figure 10-3)

[i] Is the shortest diameter through which the infant must pass

[ii] Extends from the middle of the sacral promontory to the posterior superior margin of the symphysis pubis

[iii] Can be approximated by manually measuring the diagonal conjugate, extending from the subpubic angle to the middle of the sacral promontory, then subtracting 15 cm (0.6 inch)

(b) Transverse diameter between the ischial spines

[i] The spines form the lateral boundaries of the pelvic cavity plane of least dimension (Figure 10-4).

(c) Subpubic angle (see Figure 10-2)

(e) Posterior sagittal diameters (Figure 10-5)

[i] Extend from the intersection of the transverse and anteroposterior diameters to the posterior limit of the latter

[ii] Represent the back portion of the anteroposterior diameters

(f) Curve and length of the sacrum

(3) Maternal posture influences pelvic size and contours (Fenwick & Simkin, 1987; Roberts, 1980a,b).

(a) There is no correct position; each offers advantages and disadvantages.

(b) Walking and changing positions effect changes in pelvic joints, facilitating descent and rotation.

[i] Contribute to vena caval syndrome

• Decreased placental blood flow can lead to fetal compromise.

• Decreased uterine blood flow can lead to uterine muscle hypoxia (Mayberry et al, 2000).

[ii] Decrease the ability of the patient to push voluntarily

[iii] Require expulsive forces to work against gravity

[iv] Foster dependency and passivity of patient; mirror is required for patient to see birth

[v] Provide for ease of attendant

[vi] Associated with increased incidence of interventions

Legs may be extended or knees flexed.

Legs may be extended or knees flexed.

Pelvic angle is 30 degrees, which directs the fetal head away from the pelvic inlet.

Pelvic angle is 30 degrees, which directs the fetal head away from the pelvic inlet.

Probably best reserved for rare instances when delivery difficulties anticipated

Probably best reserved for rare instances when delivery difficulties anticipated

Lithotomy: patient legs are in stirrups

Lithotomy: patient legs are in stirrups

Relaxation of the pelvic muscles facilitates descent and rotation of the presenting part.

Relaxation of the pelvic muscles facilitates descent and rotation of the presenting part.

Left side-lying may offer increased control of pushing efforts (Roberts & Woolley, 1996).

Left side-lying may offer increased control of pushing efforts (Roberts & Woolley, 1996).

Lateral Sims’, with mother lying on the side where the fetal spine is positioned, may enhance rotation from occiput posterior to occiput anterior (Ridley, 2007).

Lateral Sims’, with mother lying on the side where the fetal spine is positioned, may enhance rotation from occiput posterior to occiput anterior (Ridley, 2007).

Lateral positions associated with increased likelihood of intact perineum (Shorten, Donsante, & Shorten, 2002)

Lateral positions associated with increased likelihood of intact perineum (Shorten, Donsante, & Shorten, 2002)

Requires a support person to hold the anterior leg

Requires a support person to hold the anterior leg

May impede interaction with the attendant or infant because the delivery occurs at the woman’s back

May impede interaction with the attendant or infant because the delivery occurs at the woman’s back

[ii] Abdominal muscles work in synchrony with uterine contractions, maximizing expulsive forces; associated with a shortened second stage (Gennaro, Mayberry, & Kafulafula, 2007; Liu, 1989).

[iii] Abdominal wall relaxes, allowing the fundus to fall forward because of the force of gravity and straightening the longitudinal axis of the birth canal (Shermer & Raines, 1997).

[iv] Pelvic angle is 90 to 120 degrees, directing the fetal head to enter the pelvis in the anterior position and enhancing application of the fetal head against the cervix.

[v] Uterine contractions are more efficient.

• Gravity increases pressure to the cervix by 10 to 35 mm Hg.

• Contractions may be less frequent but of greater amplitude.

[vi] Fosters participation of patient in the birth process

[vii] Technically more difficult for some attendants

[viii] Associated with fetal and newborn well-being

[ix] Epidural anesthesia is not an absolute contraindication to upright postures (Gilder, Mayberry, Gennaro, & Clemmens, 2002; Mayberry, Strange, Suplee, & Gennaro, 2003).

• Determined by agent used as well as dosing regimen

• Requires sufficient leg strength to support maternal weight

Enlarges the pelvic outlet by approximately 28%

Enlarges the pelvic outlet by approximately 28%

Increases the efficiency and effectiveness of expulsive forces (Golay, Vedam, & Sorger, 1993; Romond & Baker, 1985)

Increases the efficiency and effectiveness of expulsive forces (Golay, Vedam, & Sorger, 1993; Romond & Baker, 1985)

Often cited as best position for second stage of labor (Roberts & Woolley, 1996)

Often cited as best position for second stage of labor (Roberts & Woolley, 1996)

Efficacy of position requires less forceful pushing and may be less tiring.

Efficacy of position requires less forceful pushing and may be less tiring.

Induces a slight separation of the lower symphysis pubis, resulting in an enlarged outlet

Induces a slight separation of the lower symphysis pubis, resulting in an enlarged outlet

Thighs are flexed and abducted, creating leverage on the innominate bones, thereby opening the bony outlet (McKay, 1984).

Thighs are flexed and abducted, creating leverage on the innominate bones, thereby opening the bony outlet (McKay, 1984).

Without the pressure of a bed, the sacrum and coccyx are easily pushed back by the descending fetus, thereby enlarging the outlet.

Without the pressure of a bed, the sacrum and coccyx are easily pushed back by the descending fetus, thereby enlarging the outlet.

Pressure of the thighs on the abdomen increases intraabdominal pressure.

Pressure of the thighs on the abdomen increases intraabdominal pressure.

Pressure is evenly distributed to the perineum, reducing the need for episiotomy.

Pressure is evenly distributed to the perineum, reducing the need for episiotomy.

Reduces visibility of perineum for the attendant

Reduces visibility of perineum for the attendant

Often used in non-Western cultures, though not customary in Western societies (McKay, 1984)

Often used in non-Western cultures, though not customary in Western societies (McKay, 1984)

Decreased muscle strength and joint flexibility can be fatiguing and uncomfortable.

Decreased muscle strength and joint flexibility can be fatiguing and uncomfortable.

Use of squatting bar provides opportunities for rest.

Use of squatting bar provides opportunities for rest.

Playing tug-of-war with support person simulates squatting while minimizing stress on thighs.

Playing tug-of-war with support person simulates squatting while minimizing stress on thighs.

Increases the pelvic diameters but not as much as squatting

Increases the pelvic diameters but not as much as squatting

May increase edema of perineum and perineal blood loss

May increase edema of perineum and perineal blood loss

Continuous pressure on lower buttocks leads to venous congestion and dependent edema.

Continuous pressure on lower buttocks leads to venous congestion and dependent edema.

— More pronounced when using a molded birthing chair, which inhibits position changes and weight shifts

Patient can unintentionally slide into a semirecumbent posture if she relies too much on back support.

Patient can unintentionally slide into a semirecumbent posture if she relies too much on back support.

(e) Kneeling postures (hands-knees)

[i] May facilitate rotation of fetus from posterior to anterior position (Biancuzzo, 1993; Stremler et al, 2005)

[ii] Coccyx is freely mobile, maximizing pelvic diameter

[iii] Are tiring for the patient

[iv] May reduce participation in birth process and interaction with the infant because the woman may be using her arms and hands to support herself

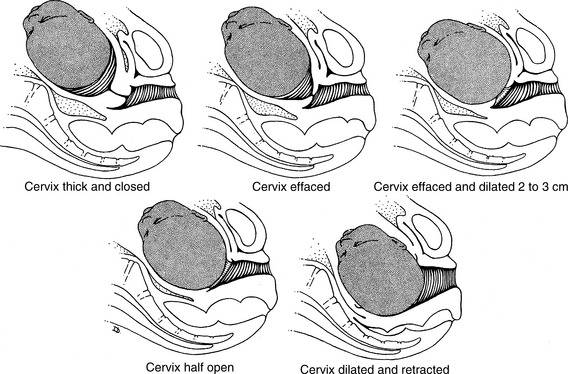

(b) Passive reduction in the length of the cervical canal from 2 cm (0.8 inch) to a paper-thin orifice

(c) Internal os disappears as cervical canal is drawn up into the lower uterine segment

(d) In nulliparas, effacement generally begins before the onset of labor.

(e) In multiparas, effacement may not begin until labor ensues.

3. Diagnostic studies and techniques

(1) Birthweight of previous children

(2) Malpresentation or disproportion encountered during previous labors

b. Current pregnancy: unusual perceptions by the patient that suggest a large infant or atypical positioning

2. Physical examination (Cunningham et al, 2005)

a. Fetal lie: relation of the long axis of the fetus to the long axis of the mother

(1) Longitudinal lie: The long axes of the fetus and of the mother are parallel.

(2) Transverse or oblique lie: The long axis of the fetus is perpendicular to the long axis of the mother.

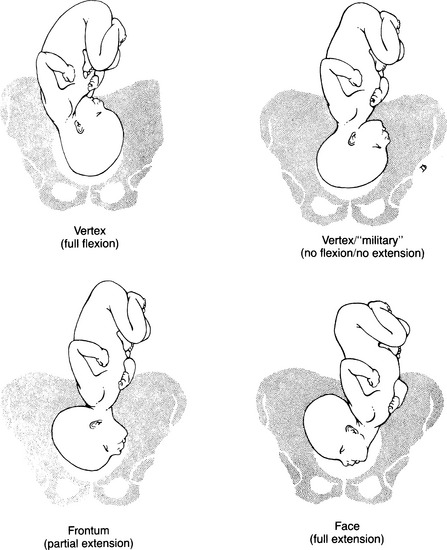

b. Fetal attitude: the relation of fetal parts to one another

c. Presentation: determined by the pole of the fetus that first enters the pelvic inlet

d. Presenting part: the specific fetal structure lying nearest to the cervix

(1) Determined by the attitude of the fetus

(2) Each presenting part has an identified denominator that is used to describe the fetal position in the pelvis.

(3) Cephalic presentations (Figure 10-7)

(a) Vertex (denominator is occiput)

• Normal fetal position, with infant’s chin resting on the chest

• Presents optimal fetal dimensions during labor

[ii] No flexion and no extension

(b) Frontum or brow (denominator is frontum)

[iii] May be related to fetal anomaly

[iv] May be associated with polyhydramnios or a small fetus

[v] Presents relatively larger fetal diameters to pelvis

[vi] Spontaneous delivery possible if pelvis is large, contractions are adequate, and infant is small

[vii] Delivery expedited by conversion to vertex or face presentation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree