Chapter 11 Environmental health

Introduction

Our understanding of how the environment can impact on human health has evolved and expanded over the centuries, with concern and interest dating back to ancient times. For example, over 4000 years ago, a civilisation in northern India tried to protect the health of its citizens by constructing and positioning buildings according to strict building laws, by having bathrooms and drains, and by having paved streets with a sewerage system (Rosen 1993).

In more recent times, the ‘industrial revolution’ played a key role in shaping the modern world, and with it, the modern public health system. This era was marked by rapid progress in technology, the growth of transportation and the expansion of the market economy, which led to the organisation of industry into a factory system. This meant that labour had to be brought to the factories and by the 1820s, poverty and social distress (e.g. overcrowding, and infrequent sewage and garbage disposal) was more widespread than ever. These circumstances, therefore, led to the rise of the ‘sanitary revolution’ and the birth of modern public health (Rosen 1993).

What is environmental health?

Many people think that environmental health refers to the health of the environment. This view conjures images of wilderness, rivers and oceans, and is a term that is synonymous with environmental protection. For others, environmental health is recognised as human health issues associated with poor living conditions, contaminated water and vermin infestation, all old battles that were fought – and generally won – over the past century. Unfortunately, both views are wrong (however, the second view could be considered the ‘old’ view of environmental health). The easiest way to describe environmental health is to say that it is ‘concerned with creating and maintaining environments which promote good public health’ (enHealth Council 1999 p 1). There are a large range of definitions of ‘environmental health’ and two of these that provide differing perspectives are:

Those aspects of human health including quality of life, that are determined by physical, chemical, biological and social factors in the environment. (enHealth Council 1999 p 3)

Focuses on the health inter-relationships between people and their environment, promotes human health and wellbeing, and fosters a safe and healthful environment. (Milne 1998)

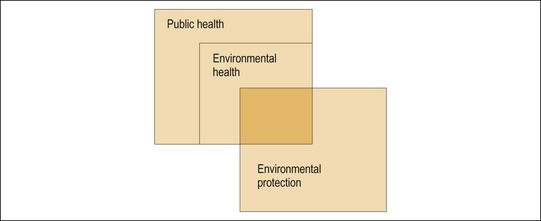

It is clear from these definitions that environmental health is an integral component of the broad field of ‘public health’ but also has some overlap with the field of ‘environmental protection’. The relationship between these areas is shown in Figure 11.1.

Environmental health hazards

An important concept associated with managing the risks posed by these hazards is ‘risk transition’. This term is used to describe the reduction in ‘traditional risks’ and the increase in ‘modern risks’ that takes place with advances in economic development. However, when environmental health risks are poorly managed, both the traditional and modern risks threaten the health of the community, whereas when environmental health risks are well managed, the traditional risks can be almost completely eliminated and the modern risks can be reduced through effective prevention programmes (WHO 1997). Overall, the following are considered to be the basic requirements for a healthy environment:

Air pollution

Air pollution is ‘the result of emission into the air of hazardous substances at a rate that exceeds the capacity of natural processes in the atmosphere (e.g. rain and wind) to convert, deposit or dilute them’ (Yassi et al. 2001 p 180). Air pollution can have the following effects:

From an environmental health perspective, we are mainly interested in the human health effects of air pollution. On a worldwide scale, the WHO estimates that over 3 million people die each year from indoor and outdoor air pollution (WHO 2008), with many more people suffering from disabling or restrictive health conditions (e.g. asthma and other respiratory conditions). Of particular concern is the widespread use of biomass fuels and coal by over half of the world’s population. These fuels are used for cooking and heating in homes across the developing world and produce substantial quantities of particulate air pollution that are often trapped within the homes due to poor ventilation. This causes over 1.9 million deaths a year from indoor air pollution-related respiratory diseases (WHO 2008). In contrast, developed countries are more concerned about outdoor air pollution. For Australia, it is estimated that outdoor air pollution is responsible for around 3000 deaths each year (roughly 2.3% of all deaths), costing New South Wales alone around $4.7 billion a year in health costs (NSW Health).

Safe water

Water and sanitation is one of the primary drivers of public health. I often refer to it as ‘Health 101’, which means that once we can secure access to clean water and to adequate sanitation facilities for all people, irrespective of the difference in their living conditions, a huge battle against all kinds of diseases will be won. (WHO 2004)

As a resource, water is our most important one. However, despite the large amount of water that makes up our planet, only a small amount is suitable and available for drinking. For example, only 2.5% of water is fresh water and of this only 0.5% is accessible for drinking because the rest of it is frozen in glaciers or the polar ice caps, or is unavailable in the soil (NHMRC 2004).

For Australia, water is a particularly fragile resource. We are one of the driest continents and are highly dependent on rainfall to supply our drinking water. However, our rainfall is extremely variable from year to year and season to season. In Australia, agriculture is by far the biggest user of water (approximately 50%) while households use about 12% of the total water supply (ABS 2010). Despite all of the water supplied to homes being of a drinkable quality, only 1% is used for drinking. The rest is used on the garden, for cooking, washing clothes, showering and flushing the toilet. Thankfully, the water-wise message seems to be taking hold, with water consumption decreasing substantially over the last decade, with some users such as agriculture cutting their usage by over 50%, and households reducing usage by about 25% (ABS 2010). Clearly, sustainable water usage should be an ongoing priority for governments, industry and consumers alike (Box 11.1).

Box 11.1 The global water crisis

The 2006 Human Development Report from the United Nations Development Programme focused on the ‘global water crisis’. It identified that access to water is a basic human need and a fundamental human right; however, more than 1 billion people are denied access to clean water and 2.6 billion people lack access to adequate sanitation. The gulf between rich and poor countries also exacerbates the ‘global water crisis’ and is illustrated in the following statements: ‘while basic needs vary, the minimum threshold is about 20 litres a day. Most of the 1.1 billion people categorised as lacking access to clean water use about five litres a day – one-tenth of the average daily amount used in rich countries to flush toilets’; and ‘dripping taps in rich countries lose more water than is available each day to more than 1 billion people’ (UNDP 2006).

From a public health perspective, water can be contaminated with pathogenic microorganisms and with a range of chemical and other substances (Case Study 11.1). Water provides the vehicle for spreading a range of communicable diseases and these can be classified as follows:

Case Study 11.1 Chemical contamination of drinking water

In 1993 arsenic contamination of water from tube-wells was confirmed and it is now estimated that up to 77 million people are at risk of drinking this contaminated water. Unfortunately, the cost of removing or capping the wells is prohibitive and the options for sourcing other safe water are limited. This is now considered to be the largest ever poisoning of an entire population (Smith et al. 2000).

Safe food

Food is a fundamental human need, a basic right and a prerequisite to good health. While Australia has one of the safest food supplies in the world, it is estimated that contaminated food causes between 4 and 7 million cases of gastroenteritis each year (Hall et al. 2005), costing the community around $1.2 billion (Abelson 2006).

There are a number of factors that are influencing food safety to an increasing extent, including:

Example 11.1 The cost of supplying prawns to Scots

A total of 19 000 km is the round-trip journey planned for prawns caught in Scottish waters before they reach British stores. The seafood firm that catches the prawns calculates that hand peeling in Thailand will be cheaper than machine peeling in Scotland with 50 cents being the hourly wage paid to Thai prawn peelers. The move will mean the loss of 120 jobs in Scotland, where workers are paid $11 per hour (Time Magazine 2006).