Chapter Eight. Empowerment

Key points

• Empowerment as a cornerstone of health promotion

• Giving information

• Enhancing self-efficacy

• Developing skills

• Enabling change

• Empowerment dilemmas in practice:

– Ethical concerns

– Effectiveness

OVERVIEW

An integral part of the World Health Organization’s definition of health promotion is empowerment – people’s ability to increase control over their health. The Ottawa Charter (WHO 1986) uses the term ‘enablement’, and identifies enablement, mediation and advocacy as key health promotion processes. The concept of ‘enablement’ in the Charter is ‘premised on the idea that in order to realize their freedom and assume greater responsibility for their health, individuals may require help in the form of know-how, resources and power to assume greater control’ (Yeo 1993, p. 233). Empowerment therefore includes having access to information, possessing the skills to use such information in practice, and having the opportunity and power to use information to make desired changes in one’s life. Empowerment is closely linked to engagement and participation. When people feel they are able to take control over their lives, they will seek the opportunity to participate in factors affecting their lives, such as planning and developing services or programmes. Such involvement (as described in Chapter 6) can also generate a sense of empowerment and control.

This chapter explores the many ways in which individuals and communities can be empowered through the provision of education and skills training. Developing the health literacy of patients, users and the public, motivational interviewing and social marketing are all strategies that are currently in vogue and share a common objective of achieving behavioural change. These three strategies will be used to illustrate the different stages of empowerment throughout this chapter.

Empowerment is the process of people acquiring more power or control over their lives. Power is ‘one of the more important determinants of people’s health, whether regarded as the psychological experiences of control or analysed as the social organization of communities, societies and economies which creates and distributes risks and vulnerabilities amongst different population groups’ (Labonte and Laverack 2008, p. 6). Empowerment can be defined as an approach which attempts to enhance health or prevent disease through the provision of information, the development of self-efficacy and skills to put knowledge into practice, and the opportunity to take control over one’s life. Empowerment strategies seek to build capacity in individuals and communities, thereby enabling them to take control, via decision making and advocacy, over the determinants of their health. This chapter explores some of the challenges for practitioners in embedding empowerment within their work and ensuring that the planning and development of empowerment strategies are equitable, ethical, client-centred, participatory and sustainable. The question of whether empowerment strategies are effective is also debated.

Introduction

The Ottawa Charter (WHO 1986) identified enablement as a core health promotion strategy, and its definition of enablement includes: ‘a secure foundation in a supportive environment, access to information, life skills and opportunities for making healthy choices’. This concept is more often referred to as empowerment, or the ability of people to affect their own lives in desired ways. The Health Promotion Glossary (Nutbeam 1998, p. 354) defines empowerment as a process through which people are able to ‘express their needs, present their concerns, devise strategies for involvement in decision-making, and achieve political, social and cultural action to meet those needs’.

For people to be empowered, they need to not only feel strongly enough about their situation to want to change it but also feel capable of changing it by having the information, support and skills to do so. Whilst health communication is an important element of empowering individuals and communities, it may also be criticized as a way of achieving support for compliance with predetermined objectives (Nutbeam 1998, p. 355). Education for empowerment means client-led learning, where people define for themselves their own needs and objectives, and the methods that are best suited to their needs. However, in practice much education in the health field is ‘expert-led’, with agendas and methods being predetermined by experts or practitioners.

Three separate elements may be identified as contributing towards the empowerment of individuals: information, attitudes and skills. In order to become empowered and to make decisions informed by knowledge, people need to have not just the correct knowledge, but also the attitude that endorses self-belief and efficacy, and the skills to put their knowledge into practice in diverse settings. Different groups will vary in their needs for each of these three components. For example, marginalized groups such as Black, Asian and minority ethnic groups (BAMEs) or people with disabilities may need more inputs around self-efficacy in order to combat their history of disenfranchisement (see Chapter 12). Young people may have the correct knowledge, but require inputs about how this knowledge can be put into practice. Older people may have the skills to effect change, but lack up-to-date knowledge about relevant issues.

Many different strategies contribute towards the empowerment of individuals and communities. Health education, or as Tones (2002) suggests, its recent reincarnation as health literacy, is a central strategy, encompassing the possession of the correct and relevant information to enable informed decisions and actions to take place. Motivational interviewing is a potentially empowering strategy for those who wish to change their behviour by employing supportive attitudes. Social marketing is a strategy which borrows advertising and marketing techniques to encourage behaviour change. Social marketing might appear to be a variant of advertising, but its adherents argue that by packaging desired behaviour and goals as socially acceptable and desirable, it becomes much easier for people to make the changes they want. These three strategies are not exhaustive, but they do provide an illustration of the range of strategies used to empower people and communities, and are discussed in greater depth later on in this chapter.

The concept of empowerment applies not only to individuals but also to communities, societies and nations. Community engagement and involvement in decision making is discussed in Chapter 6. Our companion volume Health Promotion: Foundations for Practice, edn 3 (Naidoo and Wills 2009) discusses community development as a health promotion strategy. This chapter focuses primarily on empowering individuals.

Empowerment is one tactic amongst many in the health promotion field. In order to make practical decisions about how prominent such an approach should be, and how well resourced, key questions concerning its ethical base and its effectiveness need to be answered. These two key issues are discussed in relation to specific strategies throughout the chapter.

Empowerment is the process of increasing people’s capacity to make independent choices and being able to implement those choices in practice. Empowerment therefore depends not just on the person or people making the choices, but also on the environment offering appropriate choices. Traditionally empowerment has tended to focus on people rather than environments. The empowerment process is complex, and may conveniently be divided into four different stages: acquiring the correct and relevant information; having an attitude of self-belief and self-efficacy; having the necessary skills to be able to put choices into practice; and enabling opportunities to effect change. This chapter discusses one key strategy that underpins each stage: effective communication as a means of acquiring information; motivational interviewing as a means of acquiring self-efficacy; social marketing as a means of putting choices into practice; and health literacy as a means of enabling opportunities to effect change.

Giving and providing information

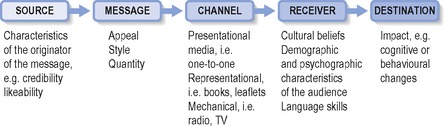

Giving health-related information to clients is a key task for most practitioners. This typically involves conveying a message about reducing risks, compliance or the effective use of services. To do this effectively, the practitioner needs to understand the audience, the best means of reaching them, and how this information will be received. There are many process models of communication, all of which adopt a mechanistic and linear orientation. The American Yale-Hovland model of communication which was designed to develop ways of influencing public attitudes and was later elaborated by McGuire (1978) is shown in Figure 8.1. It suggests that the process of mass communication entails five variables: source, message, channel, receiver and destination. The effectiveness of the communication depends on:

• the extent to which the source has credibility and trustworthiness

• the way the message is constructed and distributed

• the receiver’s receptiveness and readiness to accept the message.

|

| Figure 8.1 • A model of communication. |

Theories on behaviour change suggest that the adoption of healthy behaviour is a process in which individuals progress through various stages until the new behaviour is routinized. Behaviour models, such as the Health Belief model (Becker 1974) or the Theory of Reasoned Action (Ajzen and Fishbein 1980) or Ajzen’s later Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen 1988), which are discussed in Foundations for health promotion, edn 3 (Naidoo and Wills 2009), are based on a set of assumptions about the change process. These models show that the simple provision of information without some modification of attitudes and beliefs has little effect on behaviour. However, giving information is often the starting point for changing behaviour.

Information needs to be not just given but also received and correctly decoded. In most cases this means understanding the spoken language and/or being able to read the written language. Functional literacy (being able to read and write) is a key skill for living and learning, and there is a strong relationship between literacy and health (Parker 2000). Limited literacy has been identified as an independent risk factor for poor health, and increased health literacy is associated with improved health (Volandes and Paasche-Orlow, 2007 and Von Wagner et al., 2007). A significant percentage of the population, even in developed countries, is illiterate (estimates range from 7% to 47%; UN Development Program 2007).

Migrants and refugees may be literate in their own language, but lack literacy skills in the country they reside in. Translation and interpretation services are a necessary resource in such cases, in order to transmit and receive information. Such services are often poorly resourced and may be hard to access, particularly in areas that are not perceived as having a significant population of migrants. Using traditional channels of communication such as faith leaders or story telling and mass media such as radio or television, can also reach populations.

In any effective communication there are various stages to work through:

• Identify and understand your target audience – use knowledge about the target audience’s demographic, social and psychographic variables to identify their priorities, values, beliefs and lifestyles. This will enable you to ‘package’ your information in ways that will appeal to them.

• Design the message – this needs to be ‘packaged’ in such a way that it will appeal to the target audience.

• Make it relevant – the information needs to be perceived as relevant to ‘someone like me’.

• Make it credible – credibility may be enhanced by the use of people who are perceived to be experts, for example medical doctors; or conversely, by the use of ‘people like me’.

• Make it motivational – there needs to be an appeal to desired values or attributes in order to convince people to act on the information. Commonly used motivating values are youth, energy and attractiveness.

• Make it seem possible – this might mean acknowledging that implementing changes to behaviour is not straightforward, and including information on negotiating barriers to change.

• Arouse emotional involvement – health promotion has a long history of using fear to increase the impact of messages. Whilst fear may be a powerful motivator in the short term (Montazeri 1998), repeated use of fear leads to denial and disassociation from the message. Appeals to positive emotions, for example self-confidence, may be more effective.

Communicating the risks about swine flu

In 2009, the UK government distributed a leaflet to every household providing information about swine flu, including:

• What swine flu is and how it could spread

• What has been done to prepare for a wider outbreak

• What people can do to protect themselves

• What to do if you develop symptoms

It employed a simple message: ‘Catch it, bin it, kill it’.

To what extent does this information campaign meet the requirements for an effective behaviour change communication?

Enhancing self-efficacy

Self-efficacy is the belief in one’s abilities and skills. In order to make behavioural changes to improve health, a person needs not just the correct information but also a mindset that believes such changes are possible. This belief in one’s own abilities to make changes is fundamental to most health promotion programmes, especially in developed democratic countries where individual free will is highly valued. Rather than coercing or forcing people to adopt healthier behaviour, the over-riding tactic in such countries is education and persuasion. Health promotion therefore competes with commercial advertising and promotion, all of which seek to persuade people to adopt certain behaviour. Peer-led strategies privilege the knowledge and experience of individuals themselves and use modelling to encourage change. Practitioner-led strategies seek to motivate change through empathic discussion.

The Expert Patient Programme (EPP)

The EPP is a peer-led initiative for people living with long-term conditions. The aim of the programme is to increase people’s confidence and improve their quality of life and their ability to self-manage their condition. The EPP is a 6-week course delivered locally by a network of trainers and volunteer tutors, and is also available online. The course enables people with chronic conditions to develop their communication skills, manage their emotions, engage with the health care system and find appropriate resources, plan for the future, and understand healthy lifestyles. The EPP has developed courses for a number of marginalized groups and communities, including young people and minority ethnic groups. Evaluation of the programme has been very positive, indicating that people who have undertaken the course feel they are less likely to let their symptoms interfere with their lives, report a lessening in the severity of their symptoms, feel better prepared for medical consultations, and make less use of health services.

Motivational interviewing is a technique designed to assist people to make behavioural changes. It has its roots in clinical psychology and counselling (Miller and Rollnick 2002). Motivational interviewing has been used to help people change various types of behaviour, including alcohol and substance misuse and to achieve compliance with drug regimens. Motivational interviewing claims to be both client-centred and successful in achieving change. It seeks to help people understand the consequences and risks of adopting certain behaviour, and to become motivated to change such behaviour. Motivational interviewing is appropriate for people wherever they are in the behavioural cycle – whether they are in denial that there is a problem, or acknowledge that there is a problem but don’t know where to start to change things. ‘The strategies of motivational interviewing are more persuasive than coercive, more supportive than argumentative, and the overall goal is to increase the client’s intrinsic motivation so that change arises from within rather than being imposed from without’ (Rubak et al 2005, p. 305). These characteristics of motivational interviewing, especially its prioritizing of the principle of autonomy, ensure that it is an ethical approach.

There are five general principles underpinning motivational interviewing:

1. Express empathy – share clients’ perspectives.

2. Develop discrepancy – help clients see the discrepancy between their actual lives and how they would like their lives to be.

3. Roll with resistance – understand and accept that clients’ reluctance to change is natural.

4. Support self-efficacy – prioritize client autonomy (even if this means not accepting the need for change).

For many practitioners acknowledging a client’s resistance to change can be challenging. If an issue is not accepted by the client as important despite its health risks (e.g. smoking in pregnancy) a practitioner may feel compelled, and even see it as their ethical duty, to point this out, often using fear to emphasize the risks. Such an approach is likely to lead to denial or resistance by the client.

Effectiveness of motivational interviewing

There is a growing evidence base to support the use of motivational interviewing to achieve desired behavioural changes (Dunn et al 2001; Martins and McNeil 2009; Rubak et al 2005). Motivational interviewing has been shown to be an effective intervention for substance abuse although its effectiveness for other issues such as smoking and HIV risk has not been demonstrated (Dunn et al 2001). A more recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 72 randomized controlled trials that used motivational interviewing in relation to a variety of issues (including obesity, alcohol use and compliance with medication) showed that the use of motivational interviewing had a significant effect in approximately three quarters of the studies (Rubak et al 2005). Factors that increased the efficacy of motivational interviewing included its use by psychologists and physicians (rather than by other healthcare providers) and its use on more than one occasion. A review of 37 articles on the use of motivational interviewing to promote health behaviour in the areas of diet and exercise, diabetes and oral health concluded that this approach is effective (Martins and McNeil 2009).

Develop skills

Having information and a sense of self-efficacy are important but may not be sufficient to actually make changes in a person’s life. In order to make changes a person also needs appropriate skills in decision making, such as evaluating information, negotiating change and being assertive. Health literacy is one of the many different activities that contribute to decision-making skills.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access