22 Emergency Presentations

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

• describe the uniqueness of the emergency care environment

• outline the development of Australasian triage models

• discuss the process of initial patient assessment and triage nursing practice

• integrate emergency nursing principles and practice in initial patient care

• describe the various roles of extended nursing practice in the emergency setting

• describe the principles and practice of patient preparation for retrievals or transfers

• discuss the principles for the management of disaster victims in the emergency department

• discuss the initial nursing management of common presentations to the ED, including chest pain, abdominal pain, neurological, respiratory, poisoning, envenomation, submersion and heat illness.

Introduction

Emergency nursing practice covers an enormous range of clinical presentations. As the focus of this book is critical care, this chapter discusses conditions at the critical end of the practice spectrum. Please read in conjunction with Chapters 23 and 24, which describe the management of additional common presentations to the Emergency Department (ED): trauma and resuscitation emergencies, respectively.

Emergency nursing practice is the holistic care of individuals of all ages who present with perceived or actual physical and/or emotional alterations. These presentations are often undiagnosed and require a range of prompt symptomatic and definitive interventions. Emergency clinical practice is usually unscheduled, episodic and acute in its nature, and is therefore unlike any other type of nursing in the demands it places on nursing staff.1,2 In many instances the emergency nurse is the first healthcare professional to be in contact with an acutely ill or injured patient. Patient presentations include a full range of acuity across the spectrum of possible illnesses, injuries and ages.

Background

Emergency nursing is unique, in that it involves the care of patients with health problems that are often undiagnosed on presentation but are perceived as sufficiently acute by the individual to warrant seeking emergency care in the hospital setting. As patients present with signs and symptoms rather than medical diagnoses, refined assessment skills are paramount. Many skills required by emergency nurses are based on a broad foundation of knowledge that serves as a guide in collecting information, making observations and evaluating data, and to sort and analyse relevant information.2–6 This foundation enables an emergency nurse to communicate appropriately with other members of the healthcare team, and to implement appropriate independent and collaborative nursing interventions. Assessment is an important element of emergency care; other chapters provide detailed information on the evaluation of critically ill patients.

Emergency nurses are specialists in acute episodic nursing care, and their knowledge, skills and expertise encompass almost all other nursing specialty areas. Emergency nurses therefore possess a unique body of knowledge and skillsets to manage a wide variety of presentations across all age groups; this includes familiarity with general physical and emotional requirements of each age group as these relate to their presenting health needs.2–4 ED nurses work cooperatively with prehospital emergency personnel, doctors and other healthcare personnel and agencies in the community to provide patient care.2,3,5 Roles in the ED include triage, direct patient care, expediting patient flow, implementing medical orders, providing emotional support during crises, documenting care, and arranging for ongoing care, admission to the hospital, transfer to another healthcare facility, or discharge into the community.5,6

Triage

Central to the unique functions of an ED nurse is the role of triage; perhaps the one clinical skill that distinguishes an emergency nurse from other specialist nurses. Triage literally means ‘to sieve or sort’, and is the first step in any patient’s management on presentation to an ED.1–3

History of Triage

Triage was first described in 1797 during the Napoleonic wars by Surgeon Marshall Larrey, Napoleon’s chief medical officer,7 who introduced a system of sorting casualties that presented to the field dressing stations. His aims were military rather than medical, however, so the highest priority were given to soldiers who had minor wounds and could be returned quickly to the battle lines with minimal treatment.1,8

The documented use of triage was limited until World War I, when the term was used to describe a physical area where sorting of casualties was conducted, rather than a description of the sorting or triage process itself.8 Triage continued to develop into a formalised assessment process, with subsequent adoption for initial categorising of patient urgency and acuity within most civilian EDs.1,7,8

Development of Triage Processes in Australia and New Zealand

Australia is a world leader in the development of emergency triage and patient classification systems. In the late 1960s patients presenting to ‘casualty’ departments in Australia were not always triaged,1,2,4,5 with many EDs using random models of care; ambulance presentations were given priority and the ‘walking wounded’ seen in order of arrival. In the mid-1970s, staff at Box Hill Hospital in Melbourne developed a five-tiered system that included a time-based scale and different colours on the medical record to indicate priority.1,7,8 Subsequent modification and refinement led to the Ipswich Scale in the 1970s–80s.1,2,4,5,7 These early triage systems reinforced the concepts developed by Larrey, and established a process for patients’ presentations to be seen in order of clinical priority rather than time of attendance. In the 1990s the impact of community expectations and national health policy led to further enhancements of triage systems in Australia, and the Ipswich triage scale was adapted into the national triage scale (NTS). The NTS was subsequently tested and demonstrated to have the essential characteristics of utility, reliability and validity.1,2,4,5,7,9–11 In 1993, the NTS was adopted by the Australasian College for Emergency Medicine (ACEM) in its triage policy,7 and subsequently renamed the Australasian triage scale (ATS) as it was implemented in most EDs in Australia and New Zealand (see Table 22.1).4

TABLE 22.1 Australasian triage code

| Code | Descriptor | Treatment acuity |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Resuscitation | Immediately |

| 2 | Emergency | Within 10 minutes |

| 3 | Urgent | Within 30 minutes |

| 4 | Semiurgent | Within 1 hour |

| 5 | Non-urgent | Within 2 hours |

The ATS is now a world-leading, reliable and valid triage classification system for emergency patients, with demonstrated predictive properties for severity of illness, mortality and the need for admission.5,7,9–11 When properly applied, presenting patients should receive the same triage score no matter which ED they present to.5,9,11

The Process of Triage

All patients presenting to an ED are triaged on arrival by a suitably experienced and trained registered nurse.2,10 This assessment represents the first clinical contact and the commencement of care in the department. The ideal features of a triage area are: a well-signposted location close to the patient entrance; ability to conduct examination and primary treatment of patients in privacy; a close physical relationship with acute treatment and resuscitation areas; and appropriate resources including an examination table, thermometer, a sphygmomanometer, stethoscope, glucometer and pulse oximetry.2,4,10

As the first clinician in the ED to interview the patient, the triage nurse gathers and documents information from the patient, family and friends, or prehospital emergency personnel. Professional maturity is required to manage the stress inherent in dealing with an acutely ill patient and family members (under significant stress themselves), while rapidly making informed judgement on priorities of care for a wide range of clinical problems.10

The triage nurse receives and records information about the patient’s reason for presentation to the ED, beginning with a clear statement of the complaint in the patient’s own words, followed by historical information and related relevant details, such as time of onset, duration of symptom/s, and what aggravates or relieves the symptom/s. A brief, focused physical assessment including vital signs may be undertaken to identify the urgency and severity of the condition, and may be collected as part of the triage process to inform decision making.5,10,11 Triage assessment generally should be no longer than 2–5 minutes, balancing between speed and thoroughness.11 From the information collected, the triage nurse determines the need for immediate or delayed care,1–3 and assigns the patient a 1–5 ATS category in response to the statement: This patient should wait for medical assessment and treatment no longer than ….11

Patients with acute conditions that threaten life or limb receive the highest priority while those with minor illness or injury are assigned a lower priority. It may not be possible to categorise the patient correctly in all instances, but it is better to allocate priority on a conservative basis and err on the side of a potentially more serious problem.3,8,10,11 Importantly, a triage allocation is dynamic and can be altered at any time.5–8 If a patient’s condition changes while waiting medical assessment/treatment, or if additional relevant information becomes available that impacts on the patient’s urgency the patient should be re-triaged to a category that reflects the determined urgency.11,12 Frequent, ongoing observation and assessment of patients is therefore routine practice following the initial triage assessment.

The premise for a triage decision is that utilisation of valuable healthcare resources provide the greatest benefit for the neediest, and that persons in need of urgent attention always receive that care.1,2,4,5,11,12 Triage encompasses the entire body of emergency nursing practice, and nurses complete a comprehensive triage education program prior to commencing this role. A formal national triage training resource has been developed that provides the essential education components to promote consistency in application of the ATS.11,12

Triage Categories

After triage assessment is undertaken on arrival, patients are allocated one of five triage categories using the Australasian triage scale (ATS) (see Table 22.2). Prompt assessment of airway, breathing, circulation and disability remains the cornerstone of patient assessment in any clinical context, including triage.

TABLE 22.2 Australasian triage scale (ATS) category characteristics5,11

Triage Assessment

Patient assessment at triage has three major components: quick, systematic and dynamic. Speed of assessment is required in life-threatening situations, with the focus on airway, breathing, circulation and disability (A,B,C,D), and a quick decision on what level of intervention is required. A systematic approach to assessment is used for all patients in all circumstances, to ensure reproducibility. Finally, the triage assessment must be dynamic, in that several aspects can be undertaken at once, and acknowledging that a patient’s condition can change rapidly after initial assessment. Various assessment models are available, but fundamentally they all include components of observation, history-taking, primary survey and secondary survey.1–3,4,6,11,12

Patient History/interview

The triage interview provides the basis for data gathering and clinical decision making regarding patient acuity. After an introduction, the triage nurse asks person-specific open-ended questions. Use of close-ended questions or summative statements enables clarification and confirmation of information received, and to check understanding by the patient.12 Privacy is important to ensure that the patient is comfortable in answering questions of a personal nature. Most EDs need to balance providing an area that is private and accessible, yet safe for staff to work in relative isolation.

A large component of the triage assessment may be based on subjective data, which are then compared and combined with the objective data obtained through the senses of smell, sight, hearing and touch to determine a triage category: pulse, blood pressure, respiratory rate and characteristics, oxygen saturation, capillary return, temperature, blood glucose level. One aspect of the history that is difficult to quantify is intuition. This is that ‘sixth sense, or gut feeling’ that tells us that something not yet detectable is wrong with the patient. This unexplained sense is difficult to outline or apply scientific research models to, but it has an important role to play in patient assessment and should be acknowledged when something ‘doesn’t feel right’.6,11,12

Primary Survey

While taking a patient history, the triage nurse also simultaneously conducts a primary survey. As noted earlier, airway, breathing, circulation and neurological function (deficit) is observed. If any major problem is observed, the interview is ceased and the patient is transferred immediately to the acute treatment or resuscitation area.8

Secondary Survey and Physical Examination

A secondary survey, involving a concise, systematic physical examination, is conducted after the patient history and primary survey have been completed. The equipment used includes a thermometer, stethoscope, oxygen saturation monitor and sphygmomanometer, in combination with clinical skills. This examination is not comprehensive but focuses on the presenting complaint while avoiding tunnel vision and wrong conclusions.3,12 Remember that the patient may not be able to lie down or be exposed for an examination in the triage area, and may be distressed. The triage process should reflect a system of rapid assessment that is reproducible and adaptable to a variety of presentations.

Approaches to Triage Assessment

A range of approaches to nursing assessment is applicable to triage assessments (see Table 22.3).8 Body systems approach enables systematic examination of each body system to discover abnormalities (i.e. central nervous system, cardiovascular system, respiratory system, gastrointestinal system, etc.).6,11,12 See also the relevant ‘system-based’ chapters.

TABLE 22.3 Aids to triage assessment

| Mnemonic | Components |

|---|---|

| SOAPIE | |

| AMPLE | |

| PQRST |

Triage Assessment of Specific Patient Groups

Mental Health Presentations

Patients with psychiatric problems presenting to an ED should be triaged, assessed and treated as for other presenting patients, with particular attention to appropriate initial medical assessment and management.6,11,12 Resources outlining specific mental health triage category descriptors are readily available, and relate specific aspects of mental health presentation with clinical urgency and triage categories (see Table 22.4), including an outline of suggested responses, such as patient placement requirements based on the level of risk and urgency.6,11–14

TABLE 22.4 Examples of a mental health triage tool13

| ATS | Observation | Action |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Immediate | Severe behavioural disorder with immediate threat of dangerous violence to self or others | |

| 2. Emergency | Severe behavioural disturbance with probable risk of danger to self and others | |

| 3. Urgent | Moderate behavioural disturbance or severe distress with possible danger to self and others | |

| 4. Semi-urgent | Semi-urgent mental health problem with no immediate risk to self or others | |

| 5. Non-urgent | No behavioural disturbance or acute distress with no danger to self or others |

Paediatric Presentations

Children presenting to the ED are assessed and assigned a triage category as for adults, although vital differences in paediatric anatomy, physiology and clinical presentations should be considered (see Chapter 25). The reliance of information from parents or primary carers and their capacity to identify deviations from normal is important, particularly in supporting recognition of often subtle indicators of serious illness in infants and young children. Paediatric triage resources are available to assist in identifying physiological alterations and applying the ATS based upon identified physiological discriminators.12 Other important points to consider include:

• children may suffer rapid decompensation due to limited physiological reserves; a short time is a long time in the life of a child, and may develop serious illness in a much shorter time than for an adult.11,12,15

• children are less able to tolerate pain in either physical or psychological terms.11,12,15

• it is difficult to rationalise long waiting periods with a child or parent of a sick child. The longer they wait, the more difficult an examination becomes.11,12,15

• parents are much less tolerant of waiting times for their sick child than they would be for themselves.11,12,15

Extended Roles

Contemporary roles in many EDs have expanded to include clinical roles and functions that have emerged as a result of reengineering work practice processes in response to an increasing number of emergency presentations, and to improve performance in patient flow, waiting times, length of stay and patient satisfaction.16–18 This expanded scope of practice includes advanced clinical skills performed using agreed protocols and accreditation supported by additional education and regular periods of performance review. The role has become known as an advanced clinical nurse (ACN) or advanced practice nurse (APN),17 involving, but not limited to, the following advanced clinical skills:16,18

• venipuncture and cannulation

• administration of nurse-initiated narcotic analgesia and other medications.

Nurse-Initiated X-Rays

Nurse-initiated radiology ordering enables investigations of extremities, joints such as hips and shoulders, the chest and abdomen according to clinical protocols that list inclusion and exclusion criteria19 based on findings from the ACN’s history-taking and clinical examination. The inclusion criteria reflect well-established clinical indicators. While nurse-initiated radiology ordering is often undertaken as an extended triage nurse function, it can be performed by any accredited nurse. The use of nurse-initiated radiology, especially in association with extremity injuries, is safe and accurate, reducing both waiting time and department transit time and improving both patient and staff satisfaction.17,19–21

Nurse-Initiated Analgesia

Although pain is a common complaint in the majority of patients presenting to the ED,22,23 management has previously been insufficient, especially in relation to the timeliness, adequacy and appropriateness of analgesia administered,22,23 and resulting in poor patient satisfaction.22 To address these findings, many EDs developed nurse-initiated analgesia protocols, standing orders or pathways. Nurse-initiated analgesia protocols enable designated emergency nurses to implement analgesia regimens prior to assessment by a medical officer. These protocols are locally derived and note patient inclusion and exclusion criteria for managing mild, moderate or severe pain in both adult and paediatric patients, and often include administration of an antiemetic.22,23 A numerical pain rating scale or a visual analogue scale is used to direct the type and route of analgesia administration. Severe pain protocols outline incremental intravenous narcotic administration, including incremental and total maximum administration dosages. After administration of the initial dose, the administering nurse gives subsequent incremental doses in response to a reevaluation of the patient’s pain score and vital signs (pulse, blood pressure and respiratory rate). Protocols directed towards moderate and minor pain may include either single or incremental IV analgesia or oral analgesia. Nurse-initiated analgesia protocols have also been found to be safe and effective and to shorten the time ED patients wait for analgesia,23,24 which should assist in improving patient outcomes and satisfaction.

Clinical Initiative Nurse

The clinical initiative nurse (CIN) is a specific advanced practice role introduced to primarily provide care for waiting-room patients awaiting medical officer assessment. The role was initially introduced into levels 5 and 6 metropolitan and several large rural EDs in New South Wales, to manage and reduce ED waiting times and associated patient distress, improve ‘time seen’ rates, patient service satisfaction and patient outcomes (key performance indicators). These and similar roles are now being implemented nationally.25 The role includes initiation of treatment for lower-acuity waiting-room patients, following advanced practice protocols. The treatment provided by the CIN includes ordering of radiology and/or pathology investigations, administration of oral analgesia, review and reassessment of waiting patients (particularly those who have waited longer than their triage benchmark time), and providing information and education to waiting patients and carers regarding waiting times, ED processes and patient education. The role acts as an adjunct to the triage role, and maintains a close working relationship with the triage nurse.25–27 The CIN role has contributed to timely access to interventions, investigations and care for waiting patients, increases autonomous practice, independent decision making and enhances patient advocacy. The role also provides opportunity for the clinical and professional development of emergency nurses.26

Nurse Practitioner

Introduction of the NP has been complicated by existing nomenclature relating to advanced practice roles in nursing, with titles such as advanced specialist, clinical nurse consultant, clinical nurse specialist and advanced practice nurse used interchangeably and at times problematically in the literature,28,29 including internationally.30 Consensus is gradually emerging that the NP role is evolving and developing globally as the most significant of the advanced practice roles in modern health care.29

1. Extended practice: The scope of practice of the NP is subject to different practice privileges that are protected by legislation, and occur outside the scope of practice for a registered nurse. These extended practice privileges mean that the NP functions in a grey area that incorporates some of both medical and nursing activities.28–31

2. Autonomous practice: The NP engages in clinical practice with significant clinical autonomy and accountability, including responsibility for the complete episode of care. This autonomy means that the NP works in a multidisciplinary team in a clinical partnership role to optimise patient outcomes.28–31

3. Nursing model: Practice is firmly located in a nursing model, and an extensive, but evolving, body of literature relating to the NP role and practice.28–31

National and international experience has demonstrated a specific service that is highly regarded32–35 and in demand.36,37 The NP service provides care to many underserviced groups such as the homeless,38 women and children, the elderly,39 rural and remote communities36,40 and specialist services in acute care areas.41 Nurse practitioners are effective in managing common acute illnesses and injuries and stable chronic conditions,39 and provide an emphasis on health promotion and assessment and disease prevention.42

The Australian experience has demonstrated that pressure on EDs can be relieved when NPs manage lower priority cases. Waiting times and overall length of ED stay are significantly reduced when NPs manage triage category 3–5 presentations such as sprains and superficial wounds.37

Retrievals and Transport of Critically Ill Patients

The care of an acutely ill patient often includes transport, either within a hospital to undergo tests and procedures or between hospitals to receive a higher level of care or to access a hospital bed. The movement of critically ill patients places the patient at a higher risk of complications during the transport period,50–53 because of condition changes, inadequate available equipment to or support from other clinicians, or the physical environment in the transport vehicle. For this reason the standard of care during any transport must be equivalent to, or better than that at the referring clinical area.43,44 Safe transport of patients therefore requires adequate planning and stabilisation from a team of staff with appropriate skills and experience. This section focuses on the movement of critically ill patients by nurses, doctors and/or paramedics between hospitals.45,46

Retrievals

Australasia has a variety of retrieval or transport models, although most retrieval teams comprise doctors, nurses and paramedics with specialised training in critical care. The skills of the escort personnel need to match the acuity of the patient, so that they can respond to most clinical problems.47,48 Retrieval team staff therefore need to deliver high-level critical care equal to the standard of the receiving centre, but need to be familiar with the challenges associated with working outside the hospital environment. Standards for the transport of critically ill patients have been established by the College of Critical Care Medicine (CICM) and the Australian College of Emergency Medicine (ACEM).48

When transporting an unstable patient it is essential that a minimum of two people focusing solely on the clinical care aspects of the patient are present, in addition to other staff transporting the patient and equipment. The transport team leader is usually a medical officer with advanced training in critical care medicine, or for the transport of critical but stable patients, a registered nurse with critical care experience. The skillset includes advanced cardiac life support, arrhythmia interpretation and treatment and emergency airway management.48

Preparing a Patient for Interhospital Transport

Adequate and considered preparation of the transport of a critically ill patient from one hospital area to another should be appropriately planned and not compromised by undue haste. While strong evidence to support a ‘scoop and run’ approach to patients in the field exists, this principle does not apply to interhospital or intrahospital transport of a critically ill patient. Appropriate evaluation and stabilisation is required to ensure patient safety during transport, including assessment of ABCs and suitable IV access.48

If potential airway compromise is suspected, careful consideration should be given to an elective intubation rather than an emergency airway intervention in a moving vehicle or a radiology department. A laryngeal mask airway is not an acceptable method of airway management for critically ill patients undergoing transport, because of the associated problems of movement.48 A nasogastric or orogastric tube is inserted in all patients requiring mechanical ventilation.

Fluid resuscitation and inotropic support are initiated prior to transporting the patient. Planning for the trip needs to include adequate reserves of blood or other IV fluid for use during transport. If the patient is combative or uncooperative, the use of sedative and/or neuromuscular blocking agents and analgesia may be indicated.51–53 A syringe pump with battery power is the most appropriate method for delivering medications for sedation and pain relief. A Foley catheter is inserted for transports of extended duration and all unconscious patients.52–54

The patient’s medical records and relevant information such as laboratory and radiology findings are copied for the receiving facility, and other documentation includes initial medical evaluation, and medical officer to medical officer communication, with the names of the accepting doctors and the receiving hospital.44,47

Patient Monitoring During Transport

• equipment for airway management, sized appropriately transported with each patient (check for operation before transport)

• portable oxygen source of adequate volume to provide for the projected timeframe, with a 30-minute reserve

• a self-inflating bag and mask of appropriate size

• handheld spirometer for tidal volume measurement

• available high-pressure suction

• basic resuscitation drugs, and supplemental medications, such as sedatives and narcotic analgesics (considered in each specific case)

• a transport monitor, displaying ECG and heart rate, oxygen saturation, end-tidal CO2, and as many invasive channels as required for pressure measurements. The monitor should have a capacity for storing and reproducing patient bedside data and printouts during transport.48

Monitoring equipment should be selected for its reliable operation under transport conditions, as monitoring can be difficult during transport; the effects of motion, noise and vibration can make even simple clinical observations (e.g. chest auscultation or palpation) difficult, if not impossible.49 As transport of mechanically-ventilated patients is associated with risk,29,56,58,59 consistent ventilation and oxygenation should be a goal; transport ventilators provide more constant ventilation than manual ventilation. An appropriate transport ventilator provides full ventilatory support, monitors airway pressure with a disconnect alarm, and should have adequate battery and gas supply for the duration of transport.47

Adverse events during transport of critically ill patients fall into two categories:46,48 (1) equipment dysfunction, such as ECG lead disconnection, loss of battery power, loss of IV access, accidental extubation, occlusion of the endotracheal tube, or exhaustion of oxygen supply (at least one team member should be proficient in operating and troubleshooting all equipment); and (2) physiological deteriorations related to the critical illness.

Multiple Patient Triage/Disaster

Disaster triage is a process designed to provide the greatest benefit to multiple patients when treatment resources and facilities are limited. Disaster triage systems differ from the routine triage system used within the ED (e.g. the ATS); system care is focused on those victims who may survive with proper therapy, rather than on those who have no chance of survival, or who will live without treatment. The system was first devised during war as a method of managing large numbers of battlefield casualties. Today it is applicable for treating multiple victims of illness or injury outside and within the hospital setting. Variations exist between states and countries regarding disaster victim triage classifications. It is therefore important to be familiar with local plans and policy.11,12

Triage of mass victims may be necessary in common situations, like vehicle collisions with multiple occupants, as well as large-scale disasters, such as earthquakes, floods, public transport incidents or explosions. The principles of triage vary little, though the methods used to communicate triage information and to match victims with available resources may differ. Triage at the scene of a major incident or disaster is commenced by the first qualified person to arrive (i.e. the one with the most medical training). This person is initially responsible for performing immediate primary surveys on all victims and to determine and communicate the numbers and types of resources needed to provide initial care and transport.8

In Australia and New Zealand, disaster systems have up to five triage categories (depending on jurisdictional and local protocols). To provide the best level of care and ensure the highest number of survivors, those who are mortally injured but alive may be given a low treatment priority, though this will almost certainly ensure their death. These decisions are therefore best made by an experienced doctor. In a situation with a large number of casualties, one or more doctors should be present at the site to lead the triage effort. Further, it is not within the scope of practice of non-physician emergency personnel to pronounce a patient dead, but properly trained ambulance or rescue personnel can recognise the signs of death for the purposes of triage until doctors can formally declare death.50,51

Emergency Department Response to an External Disaster: Receiving Patients

Disasters may produce mass victims on a scale that means routine processes and practices in the ED and hospital will be overwhelmed. The ED response to an external disaster forms part of the overall hospital response, outlined in a hospital disaster plan. These plans are reviewed regularly for currency, and practised for preparedness. The following aspects form part of the ED’s planning and response to receiving patients from an external disaster.51,52

Department Preparation

If the disaster site is close to the hospital, a significant number of disaster victims will self-evacuate from the site and arrive at the hospital without any prehospital triage, treatment or decontamination before any formal notification has been received. In this instance the ED will need to declare the incident and commence the notification process required.48 The ED may be quickly overwhelmed with arriving patients; the closest local medical facility may receive up to 50–80% of the disaster victims within 90 minutes of the incident.52 On notification of a disaster response a number of key positions should be allocated (medical coordinator, nursing coordinator, triage nurse, medical triage officer). These personnel are senior staff with specific disaster training and knowledge of the hospital’s disaster plan.48,51 Nursing and medical coordinators are responsible for allocating staff to specific duties; all designated roles are outlined on action cards available for staff to read prior to commencing their roles.52

The capacity of the ED to accommodate a large influx of patients needs to be maximised. Patients currently in the department are reviewed for a decision to admit. Patients requiring admission are transferred out of the Department to a suitable location in the hospital. Patients suitable for discharge or referral to their local medical officer, including patients with minor complaints currently waiting, should be discharged or referred to community resources. A small number of patients may need to remain in the ED, and their care will need to be prioritised in conjunction with arriving disaster victims.50–52

Areas of the department are designated to accommodate the expected severity of the victims (e.g. resuscitation room for priority 1 patients, observation areas for priority 2). Walking wounded casualties with relatively minor injuries and who are unlikely to require admission to hospital are best accommodated in a treatment area outside the ED, as this cuts congestion and increases the capacity for more significantly-injured victims to be managed.51

Additional staff members are notified from the current staff lists to participate in the disaster management. Staff members are allocated to teams to manage designated bed spaces within designated treatment areas. Additional staff from outside the ED may be deployed to assist; these staff should be teamed with routine ED staff, because of the latter’s familiarity with the layout and location of equipment and other resources. It is important to recognise the need to replace staff to avoid fatigue, especially in incidents of a protracted nature. Therefore, not all staff should be called in initially. Where possible, staff that work together on a daily basis should work in teams during the disaster period.51,52

Triage and Reception

Routine, day-to-day triage and reception processes will be ineffective when receiving large numbers of disaster victims. A registration process for disaster victims generally involves collecting minimal personal information from the patients, where possible, and the allocation of a prepared disaster hospital number used for identification and ordering investigations.8 Triage assessments will often be undertaken by both a medical officer and a nurse, and the process will be brief and focused. Most victims will have been allocated a triage tag in the field, but are reevaluated for any changes, as their condition may have deteriorated. Triage assessment is based on observations of the nature and extent of the victims’ injuries. Patients present in the ED prior to disaster notification are considered part of the disaster event and triaged in the same manner.4,7,8,52

Treatment

Treatment provided during a disaster will not reflect routine practices; priorities focus on resuscitation, identification of serious injuries, identification of patients requiring urgent surgery and stabilisation of patients for transfer out of the ED. The best overall outcome during a disaster are achieved when the routine principles of resuscitation and management are adapted to reflect the resources available.51,52

Respiratory Presentations

Patients with respiratory dysfunctions are a common presentation to the ED and are seen across all age groups. Respiratory symptoms can be associated with a broad range of underlying pathologies. This section will discuss the initial assessment and treatment of several common respiratory diseases seen in the ED. Chapter 14 provides more detailed information regarding respiratory diseases.

Presenting Symptoms and Incidence

Patients presenting with respiratory complaints can display a range of symptoms (see Box 22.1), and these may vary based on the patient’s age, the underlying cause of the symptoms and severity.

Box 22.1

Signs and symptoms commonly associated with respiratory presentations

• Dyspnoea (painful or difficulty breathing)

• Alteration in respiratory rate: tachypnoea/bradypnoea

• Alterations in respiratory depth or pattern

• Intercostal and/or subcostal recession

• Inability to speak in full sentences

• Stridor (upper airway respiratory disorders)

• Alterations in level of consciousness

Shortness of breath (SOB) or dyspnoea is a frequent complaint for patients presenting to the ED. Respiratory presentations are not isolated to any one specific patient population or age group and are encountered in patients across the lifespan. While dyspnoea is commonly associated with respiratory conditions such as asthma, pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and cardiac conditions, it has multiple aetiologies and related to disease in almost any organ system. A complaint of SOB is a significant symptom and is commonly associated with the need for hospital admission.53–55

Assessment, Monitoring and Diagnostics

On arrival, patients with respiratory complaints are assessed quickly using the ABC approach to determine any potential life-threatening disturbance that requires immediate medical assessment and/or resuscitative intervention. Initial assessment includes a thorough history focused on the presenting complaints. A detailed history often identifies the underlying process; however a high index of suspicion should be maintained for other potential causes during initial assessment.53,54 History focuses on the nature of symptoms, the timing of onset of symptoms, associated features, the possibility of trauma or aspiration and past medical history (particularly the presence of chronic respiratory conditions). During physical examination, the patient assumes a position of comfort while inspection of the chest is undertaken, followed by auscultation, palpation and percussion (see Chapter 13 for more detail).

Patients with significant respiratory symptoms are best managed in an acute monitored bed or resuscitation area of the department. An initial set of observations including heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, temperature and oxygen saturation is supported by continuous monitoring heart rate and oxygen saturation. Pulse oximetry plays an important role in the monitoring of the patient with a respiratory complaint, as recognition of hypoxaemia is significantly improved when it is used.56

IV access enables collection of venous blood samples for full blood count (FBC) and urea, electrolytes, creatinine (UEC) where clinically indicated. A chest X-ray (CXR) is ordered in most instances, and interpreted in relation to the clinical history and other examination findings.55 Spirometry or peak flow measurements enable assessment of peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR), forced vital capacity (FVC) and forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), to determine the nature and severity of the underlying respiratory condition. These tests are however effort- and technique-dependent and may not be able to be performed by a patient who is acutely SOB.55 An arterial blood gas (ABG) is often indicated in patients with a significant respiratory presentation, and provides information on oxygenation, ventilation and acid–base status.55

Oxygen therapy is commenced early for a patient presenting with signs of acute respiratory compromise, including those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); importantly, patients with acute hypoxia require oxygen. Any potential detrimental effects are uncommon, and concentration and time dependent with a slow onset; this allows for monitoring (pulse oximetry, ABG analysis) and clinical review.55,57

Candidate Diagnoses and Management

Asthma

Asthma is a very common patient presentation to Australasian EDs. Over 2.2 million Australians have asthma, with 16% of children and 12% of adults affected by the condition.58–61 Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease of the airways with many cells and cellular elements playing a role (mast cells, eosinophils, T lymphocytes, macrophages, neutrophils and epithelial cells). Inflammatory changes cause recurrent episodes of wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness and coughing associated with widespread reversible airflow obstruction of the airways. This airflow obstruction or excessive narrowing results from smooth muscle contraction and swelling of the airway wall due to smooth muscle hypertrophy, inflammatory changes, oedema, goblet cell and mucous gland hyperplasia and mucus hypersecretion.61

Normally, airways widen during inspiration and narrow in expiration. In asthma, the above responses combine to severely narrow or close the lumen of the bronchial passages during expiration, with altered ventilation and air trapping.58–60 The causes of asthma are related to many factors, including allergy,58 infection (increased reaction to bronchoconstrictors such as histamine),58,59 irritants (e.g. noxious gases, fumes, dusts, dust mites, powders), or heredity (although the exact role or importance of any hereditary tendency is difficult to assess).59

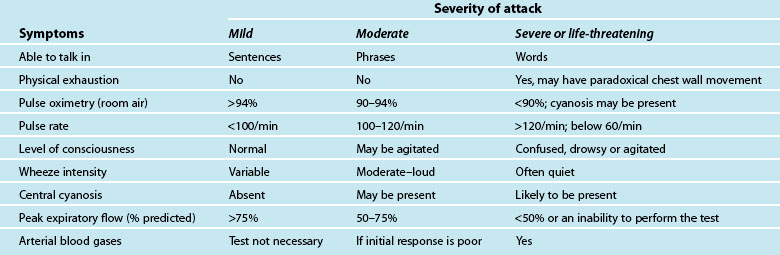

A patient usually has a history of previous asthma attacks. Often, an acute episode follows a period of exercise or exposure to a noxious substance, or a known allergen.58,60 The onset of the asthma may be characterised by vague sensations in the neck or pharynx, tightness in the chest with breathlessness, loose but non-productive cough with difficulty in raising sputum, difficulty breathing, particularly on expiration, with increasing severity as the episode continues; apprehension and tachypnoea may follow as the patient becomes hypoxic, with audible wheezing.58,60 The characteristics and initial assessment of acute mild, moderate and severe/life threatening asthma in adults and associated clinical management guidelines are outlined in Table 22.5.61,62

Be alert to the high-risk patient whose ability to ventilate is impaired: this is a life-threatening condition. These patients will exhibit an inability to talk, central cyanosis, tachycardia, use of respiratory accessory muscles, a silent chest on auscultation, and a history of previous intubation for asthma.55,57–59 See Chapters 14 and 15 for ongoing management.

Acute Respiratory Failure

Acute respiratory failure occurs when the lungs provide insufficient gas exchange to meet the body’s need for O2 consumption, CO2 elimination, or both. Acute respiratory failure results from a number of causes63 (see Chapter 14). When alveolar ventilation decreases, arterial O2 tension falls and CO2 rises. This rise in arterial CO2 produces increased serum carbonic acid and pH falls, resulting in respiratory acidosis.63 If uncorrected, low arterial O2 combines with low cardiac output to produce diminished tissue perfusion and tissue hypoxia. Anaerobic metabolism results, increasing lactic acid and worsening the acidosis caused by CO2 retention. Other symptoms develop involving the central nervous and cardiovascular systems.59,60,63 ABGs confirm the diagnosis, with hypercarbia (PaCO2 >45 mmHg and hypoxaemia (PaO2 <80 mmHg), and a low pH evident. A CXR identifies the specific lung disease.63

Clinical management focuses on correction of hypercapnia, treatment of hypoxaemia, correction of acidosis, and identification and correction of the specific cause63 (see Chapter 14). For a spontaneously breathing patient, administer oxygen by ventilation mask (24%) or nasal cannula. Adjust oxygen therapy according to ABG findings at 15–20-minute intervals to achieve a PaO2 of 85–90 mmHg. For a patient with inadequate respiratory effort, non-invasive ventilation may be instituted. In an apnoeic situation, initiate ventilatory assistance with bag–mask ventilation prior to endotracheal intubation, then commence mechanical ventilation (see Chapter 15).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree