Chapter 18 Emergencies in the immediate puerperium

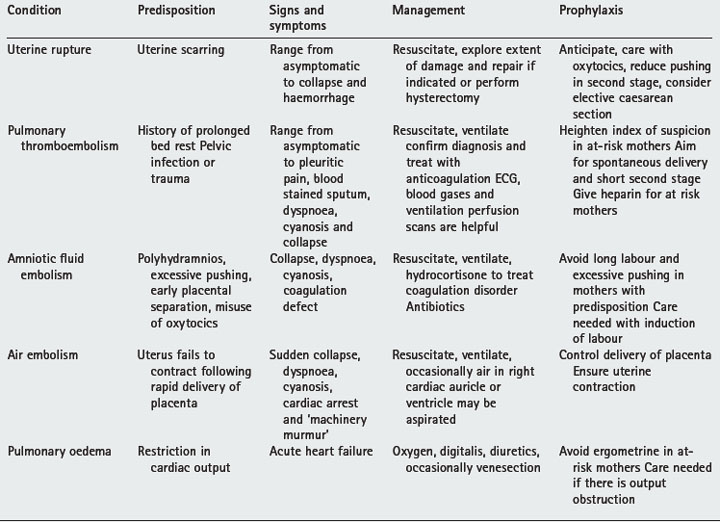

The exertions of labour and delivery subject women to potential risks (summarised in Table 18.1) because:

• Strong contractions threaten uterine rupture in any scarred uterus. Pelvic vein thrombi may be dislodged to cause pulmonary embolus and increased intrauterine pressure can squeeze amniotic fluid into the venous sinuses to produce amniotic fluid emboli. Following delivery uterine retraction injects up to 500 ml of sequestrated blood into the circulatory system. Women with restricted cardiac output may develop pulmonary oedema.

• Increased intra-abdominal, intrathoracic and intracranial pressures are associated with pushing efforts during delivery. Aneurysms (e.g. splenic or intracranial) or lung bullae (following chronic lung disease) can rupture.

• Placental and membrane separation expose a large area with open venous sinuses. Some bleeding is inevitable but postpartum haemorrhage can result if the myometrium fails to contract or is prevented from doing so. Occasionally a vacuum is created after expulsion of the placenta and air can be sucked in to produce air emboli.

• Stress and exertion can aggravate existing medical conditions, such as epilepsy or adrenal insufficiency. A difficult labour can have psychological sequelae.

POSTPARTUM HAEMORRHAGE

Bleeding in excess of 300 ml after delivery is considered excessive. By convention, a loss of 500 ml or more is described as a haemorrhage. True postpartum haemorrhage is bleeding after delivery of the placenta, an academic point of little practical value. Bleeding is further classified as primary (within 24 hours of birth) and secondary (after 24 hours after birth).

Complications

• Anxiety. Haemorrhage is a frightening experience and all women and their partners appreciate a full explanation and reassurance.

Box 18.1 Pulmonary thromboembolism

• Prevention is by subcutaneous heparin 5000–10 000 IU preoperation and then twice daily (maintain anti-factor Xa levels below 0.3 IU/ml) or equivalent such as Fragmin 2500 IU subcutaneously 1-hours before surgery and then daily until fully mobile to cover labour or caesarean section. Bleeding is more likely if prothrombin time is more than 2.5 times control or the heparin level exceeds 0.5 IU/ml. Pre-eclampsia, renal impairment and aspirin ingestion reduce heparin requirements.

• Women with anti-thrombin III deficiency are at particular risk. During labour and the early puerperium give anti-thrombin III infusions or equivalent. Heparin is not useful because its action depends on anti-thrombin III.

• Women with mitral valve disease or prosthetic heart valves are usually given intravenous heparin before delivery at levels of 0.8 IU/ml. Reduce levels to one-third during labour and raise again in the puerperium.

• Pulmonary embolism is often symptomless. If possible confirm diagnosis. Treatment is by heparin 40 000 units daily by intravenous infusion (anti-factor Xa levels of 0.5–1.5 IU/ml; partial thromboplastin time of 1.5 to 2.5 times control) for 1 week before changing the regimen.

Predisposing factors

• Poor uterine contraction/retraction, for example in a grand multipara (more than four babies), or where the uterus is previously overdistended, for example a multiple pregnancy or polyhydramnios).

• An episiotomy can contribute up to 150 ml of blood loss. Episiotomies must be repaired quickly to reduce blood loss.

Management

• Anticipate. Set-up intravenous infusion and reserve cross-matched blood for at-risk women. Ergometrine, 0.25 mg intravenously, encourages uterine contraction. Following antepartum haemorrhage coagulation defects must be excluded before delivery or surgery.

• An experienced person should conduct the delivery of at-risk women. Active management of third stage is suggested.

• Treat shock. Untreated severe shock for more than 30 minutes will result in Sheehan’s syndrome in 40% of mothers. Select crystalloid, colloid, cross-matched bloods or O negative blood (emergency) in sequence.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree