Introduction

Rule 5 of the Midwives’ Rules and Standards (NMC 2012) identifies midwives’ obligations and scope of practice. The standard that accompanies this rule states that in an emergency situation or where there is a deviation from the norm, the midwife must refer to another healthcare professional who is expected to have the required skills and experience to assist in providing care (NMC 2012).

The Clinical Negligence Scheme for Trusts (CNST) was set up by the NHS Litigation Authority to handle clinical negligence claims against member NHS bodies. The CNST requires annual multidisciplinary practice sessions or ‘drills’ so that staff members can practise their specific roles in an emergency situation.

The emergency situations to be discussed are those identified in the Standards for Pre-registration Midwifery Education (NMC 2009), NHSLA (2012) and Saving Mothers’ Lives (CMACE 2011). They are:

- maternal resuscitation

- neonatal resuscitation

- shoulder dystocia

- vaginal breech delivery

- manual removal of the placenta

- manual examination of the uterus

- management of postpartum haemorrhage

- management of an eclamptic seizure.

With each of these emergency situations, factors that increase the risk of occurrence will be identified. This will facilitate anticipation of problems that might affect delivery.

Maternal resuscitation

Incidence

Cardiac arrest is estimated to occur in 1:30,000 late pregnancies (Morris & Stacey 2003). However, in the 2006–2008 triennium the maternal mortality rate was 11.39 per 100,000 maternities which is equal to 1:8779 women from pregnancy to 1 year after the birth (CMACE 2011).

Risk factors

The most common cause of maternal cardiac arrest, regardless of aetiology, is hypovolaemia and hypotension (Morris & Stacey 2003).

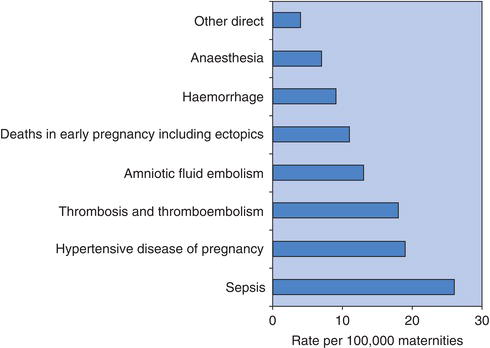

The factors that increase the requirement for maternal resuscitation vary but include those identified by CMACE (2011) as being the leading causes of direct maternal death (due to pregnancy), shown in Figure 8.1.

Certain physiological changes that occur in pregnancy may have an impact on maternal resuscitation:

- Increase in cardiac output by 30–40%: this starts as early as 4 weeks’ gestation to promote maternal adaptation to pregnancy, as well as the blood supply to the enlarging uterus.

- Increase in blood volume by up to 50%: the uterine blood flow increases from 100 mL/min at the end of the first trimester to 500 mL/min by term (Heideman 2005). It results in a fall of haemoglobin due to the effect of haemodilution.

- Increased oxygen consumption of 20%.

- Decreased peripheral resistance: this is due to both development of the uteroplacental circulation and relaxation of the peripheral vascular tone.

- Decreased residual capacity of the lungs of 25%.

- Delayed emptying of stomach contents: this leads to an increase in volume and acidity of the gastric contents.

- The weight of the pregnant uterus: this can lead to aortocaval compression when a woman is lying in a supine position, particularly after 20 weeks’ gestation. The weight presses on the aorta and vena cava, restricting blood flow to vital organs such as the brain and heart, causing a reduction in cardiac output and hypotension.

Figure 8.1 Mortality rates per million maternities of leading causes of direct deaths: United Kingdom 2006–2008 (CMACE 2011).

The Resuscitation Council (UK) currently sets the standard for maternal resuscitation and produces training aids and literature. Figure 8.2 shows the algorithm for basic adult resuscitation.

In pregnancy, physiological changes can complicate the resuscitation procedure and particular attention should be paid to minimising aortocaval compression. The uterus needs to be tilted to the left by 25–30º. This can be achieved by:

- using a firm triangular wedge present in many maternity units, or a pillow

- using a human wedge, i.e. knees

- using a tipped-up chair

- performing manual uterine displacement. This is when an attendant manually lifts the weight of the uterus to the left, off the woman. Aortocaval compression will be relieved by this method and cardiac output increased by 20–25%, but it may interfere with effective chest compressions. Cardiac output is reduced to approximately 30% of normal during effective cardiopulmonary resuscitation and its effectiveness depends on the efficacy of external chest compressions (Lee et al. 1986, Resuscitation Council UK 2010a, Ueland et al. 1972).

Figure 8.2 Algorithm for basic adult resuscitation. Reproduced by kind permission of the Resuscitation Council UK (2010a).

Image not available in this digital edition.

Perimortem (at or near the time of death) caesarean section may have to be undertaken early in the resuscitation attempt in order to relieve aortocaval compression, increase venous return and increase cardiac output. If it is done within 4–5 min of the cardiac arrest, the likelihood of maternal and neonatal survival is increased.

In all cases it is imperative that staff with the appropriate experience are present when dealing with a cardiac arrest in a pregnant woman. These are an obstetrician, anaesthetist and neonatologist. Particular attention should be paid to effective cardiac compressions. A rate of 30 compressions to two breaths is recommended.

Once expert help arrives:

- incorporate early advanced airway intervention

- apply pressure to the cricoid cartilage to occlude the upper end of the oesophagus against the vertebrae and prevent the acid gastric contents from being aspirated

- treat causative factors such as hypovolaemia or toxicity.

If the situation occurs in an out-of-hospital setting, then the emergency services need to be mobilised and basic resuscitation must continue with the woman tilted to the left until expert help is available.

Neonatal resuscitation

Incidence

A large study in Sweden indicated that 10 per 1000 babies over 2.5 kg required either mask inflation or intubation. Of these, eight per 1000 responded to mask inflation and two per 1000 required intubation (Palme-Kilander 1992). There is no corresponding information available for the UK.

Risk factors

The factors that increase the requirement for neonatal resuscitation vary and it is not easy to predict which babies will require resuscitation at birth. Therefore, everyone who attends births should be trained in newborn life support.

Babies who require resuscitation do so for different reasons from an adult. Physiologically, a newborn baby is prepared to withstand a lack of oxygen for periods during labour and birth. Generally, they are born with strong hearts, and the initial help they need is with respiration. Their lungs are filled with fluid at birth so to resuscitate a newborn baby, it is usually sufficient to inflate the lungs with air or oxygen. The heart will normally still be pumping and so will bring oxygenated blood back to the heart from the lungs, leading to recovery. Rarely, the heart may need to be ‘bump’ started (defibrillated). Figure 8.3 shows the algorithm for newborn life support.

Newborn life support consists of the following.

Drying and covering the baby to conserve heat

Drying the baby will provide stimulation and allow time for assessment of colour, tone, breathing and heart rate. Babies who become cold following birth are less able to maintain oxygen levels and become hypoglycaemic. The use of food-grade plastic wrapping is recommended by the Resuscitation Council UK (2010b) to maintain body temperature in significantly preterm babies.

Assessing the need for any intervention

Most babies when dried and kept warm will spontaneously start to breathe within 60–90 seconds of birth. A normal heart rate is 120–150 beats/min. This is best judged by listening with a stethoscope.

If meconium is present, do not aspirate it from the nose and mouth while the head is on the perineum as it is of no benefit and does not prevent meconium aspiration syndrome. Do not remove meconium from the airways of crying babies for the same reason. However, if babies are not crying at birth and meconium is seen in the oropharynx, this can be cleared with the use of a stiff Yankauer sucker, although there is no evidence of the efficacy of this practice.

Opening the airway

The baby should be placed on its back with its head in the neutral position, i.e. with the neck neither flexed nor extended. A folded towel may be placed under the shoulders to aid positioning if the baby has a prominent occiput (back of head). However, it is important to ensure the neck is not overextended when doing this. If the baby’s tone is very poor, it may also be necessary to apply a chin lift or jaw thrust. This may be enough to enable air to enter the lungs to initiate the process of life.

Figure 8.3 Newborn life support. Reproduced by kind permission of the Resuscitation Council UK (2010b).

Image not available in this digital edition.

Breathing

If a newborn does not make an effort to breathe, it will be appropriate to assist the process by giving up to five inflation breaths which need to last for 2–3 seconds each to be effective. This is because there may be no or limited chest movement for the first 2–3 inflations due to the movement of fluid from the lungs or poor positioning of the mask.

Aerating the lungs triggers the neural centres in the brain responsible for normal breathing to function and the majority of newborns will recover. Air may be used initially, although oxygen should be available in case there is no rapid improvement in the newborn baby’s condition.

If the baby’s heart rate increases but spontaneous breathing is not initiated, then regular breaths should be provided at a rate of approximately 30–40/min until the baby starts to breathe on its own.

If there is no evidence of lung inflation, consider the following:

- Is the baby’s head in the neutral position?

- Do you need jaw thrust?

- Do you need a longer inflation time?

- Do you need a second person’s help with the airway?

- Do you need to remove an obstruction in the airway using a laryngoscope and wide-bore suction?

- What about an oropharyngeal (Guedel) airway?

There is no point in progressing until there is evidence that air is entering the lungs, so repeat the inflation breaths.

Chest compression

In a few cases, the cardiac function will have deteriorated so that oxygenated blood is not transferred from the aerated lungs to the heart. If the heart rate remains below 60 beats/min following effective inflation breaths, chest compressions will be required.

The recommended method of delivering chest compressions is to grip the chest with both hands so that the two thumbs can press on the lower third of the sternum, with the fingers over the spine at the back. The chest should be compressed quickly and firmly by about one-third of the depth at a ratio of 3:1 compressions to inflations. A rate of 90–120 compressions/min should be aimed for. The aim is to move oxygenated blood from the lungs back to the heart. It is important to allow enough time during the relaxation phase of each compression cycle for the heart to refill with blood.

Administration of drugs (rare)

In the rare event that lung inflation and chest compressions are insufficient, drugs may be required to restore the circulation. The outlook for this group of babies is poor.

Stopping resuscitation

The Resuscitation Council UK (2010b) states that ‘In a newly-born baby with no detectable cardiac activity, and with cardiac activity that remains undetectable for 10 min, it is appropriate to consider stopping resuscitation’. However, the midwife’s responsibility is to continue resuscitation until care is transferred to an appropriate practitioner (NMC 2012).

Shoulder dystocia

While caring for mothers in labour, midwives are constantly monitoring progress in order to predict and react to unfolding events. The rate of progress in labour and particularly the second stage is predictive of the possibility of obstruction during the delivery. Shoulder dystocia is one such delay.

Definition

Shoulder dystocia is best defined as an impaction of the anterior shoulder of the fetus against the maternal symphysis pubis after the fetal head has been delivered. Any measures aimed at expediting delivery concentrate on changing the relationship between the two bony parts. Gibb (1995) described three types of shoulder dystocia, increasing in severity:

Incidence

The incidence of shoulder dystocia is generally agreed to be 0.6–0.7% (RCOG 2012).

Risk factors

Before labour, a history of the following features is known to increase the risk of shoulder dystocia:

- Previous shoulder dystocia.

- Macrosomic baby (estimated > 4.5 kg).

- Diabetes mellitus.

- Maternal Body Mass Index (> 30 kg/m2).

- Induction of labour.

During labour, the following scenarios also indicate an increased risk of shoulder dystocia:

- A prolonged first or second stage of labour.

- A secondary arrest of labour requiring oxytocin augmentation.

- An assisted vaginal delivery.

Although these risk factors are commonly cited, they are of reasonably poor predictive value and it is important to remain vigilant in all cases (AAFP 2000, RCOG 2012).

Management

The manoeuvres described here are currently recommended to assist practitioners to relieve a shoulder dystocia. They are described from the simple to the more complex, but this order is not prescriptive. Organisations such as ALSO (AAFP 2000) recommend the use of the mnemonic HELPERR:

- Help

- Evaluate for episiotomy

- Legs (McRoberts manoeuvre)

- Pressure (suprapubic)

- Enter (for manoeuvres)

- Remove (the posterior arm)

- Roll (the patient either into all-fours or through 360°)

Each manoeuvre should take a maximum of 1–2 min and if unsuccessful, it is important to move on to another.

Help

The first action of the midwife is to confidently diagnose a shoulder dystocia and call for help. Once help is on its way, the measures described below should be commenced. In a community setting, help will be requested from the paramedics by dialling 999. Simple measures may be worth considering in the first instance, such as rolling the mother onto all-fours or, in a birthing pool, encouraging her to stand up and place one foot on the edge of the pool to assist delivery.

Evaluate for episiotomy

It is widely accepted that in the event of a shoulder dystocia occurring, an episiotomy is desirable to prevent further damage to the mother’s pelvic floor and to provide space for the ‘enter’ manoeuvres. However, once the baby’s head has delivered, it is technically very difficult to ensure that the procedure does not damage the baby.

Legs (McRoberts manoeuvre)

This involves placing the mother flat on her back and putting her knees on her chest. Once she is in this position, attempts should be made to deliver the baby. The manoeuvre is aiming to:

- rotate the symphysis pubis anteriorly

- push the posterior shoulder over the sacrum

- open the pelvic inlet to its full capacity

- correct any maternal lordosis

- remove the sacral promontory as an obstruction.

If the manoeuvre is unsuccessful it is suggested that it is repeated before moving on to another. The McRoberts position is a relatively safe intervention with a good rate of success of 40–50%.

Pressure (suprapubic)

The aim of applying suprapubic pressure is to displace the anterior shoulder from the symphysis pubis and allow it to enter the pelvis. This action is sometimes referred to as Rubins 1 and is undertaken as follows:

- Pressure is applied by the midwife or an assistant to the mother’s abdomen, above the baby’s back, in a downward direction towards the side of the mother that the baby is facing.

- Whilst this pressure is applied, the delivering midwife will continue to try to deliver the baby with gentle traction. The pressure should initially be continuous. If unsuccessful, the assistant can be asked to provide suprapubic pressure as a rocking movement.

These manoeuvres have been shown to be effective in 67% of cases of shoulder dystocia cases (Luria et al. 1994).

Enter (for manoeuvres)

The ‘enter’ manoeuvres aim to rotate the shoulders. They are also known as Rubins 2 and the wood screw manoeuvres and are often combined to expedite delivery.

- Rubins 2: working from behind the baby, the anterior shoulder is located with the fingers and pushed into the oblique. This aims to reduce the diameter of the shoulders.

- Wood screw manoeuvre: at the same time, the fingers of the other hand can be used to add pressure to the front of the posterior shoulder to aid rotation of the shoulders into the oblique diameter. If at any time during the manoeuvre it is seen that the baby has moved, an attempt to deliver should be made.

- Reverse wood screw: if no movement is achieved, the fingers from in front of the posterior shoulder should be removed and the fingers behind the anterior shoulder can be slid down to behind the posterior shoulder and pressure applied in the opposite direction to rotate the baby.

For the ‘enter’ manoeuvres, the mother should be placed in the lithotomy position or, if at home, the McRoberts position. Suprapubic pressure can also be continued.

Remove (the posterior arm)

If the previous endeavours have been unsuccessful the last of the ‘enter’ manoeuvres is when an attempt to deliver the posterior arm is made. The midwife enters her fingers in front of the baby’s body and locates the lower arm. Pressure is exerted on the elbow to try to make the lower arm raise; this is then grasped and gently pulled across the baby’s face in a ‘cat lick’ motion, thereby delivering the posterior shoulder

Roll (the patient either onto all-fours or through 360º)

This position optimises the sacral curve and is in effect a McRoberts manoeuvre upside down. With the mother on all-fours, she can be encouraged to rock, thereby mimicking the movement of the legs when in the McRoberts position. This is therefore a useful tool when delivering in a birth centre or in the mother’s home.

If these manoeuvres are unsuccessful, the whole round of procedures should be performed again. It is recommended that this is undertaken by another midwife or obstetrician if available.