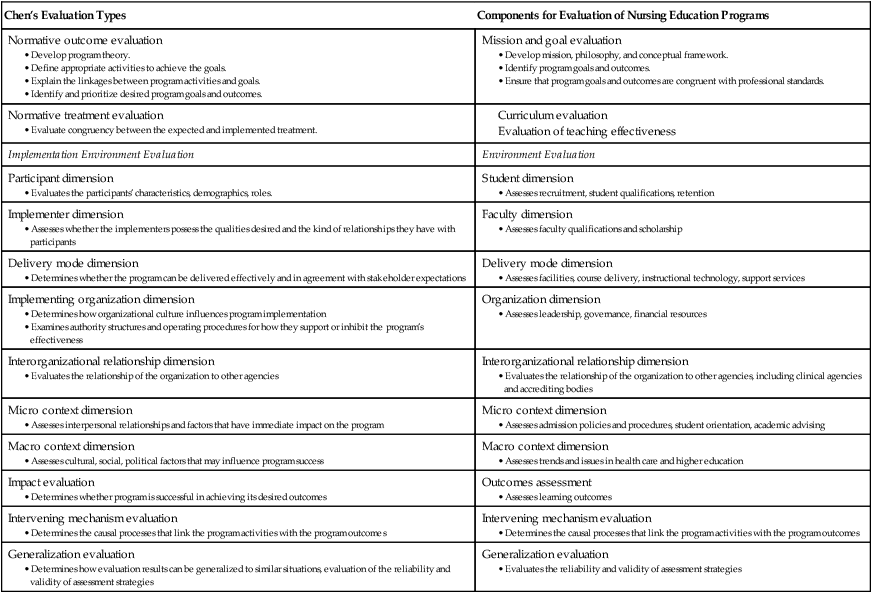

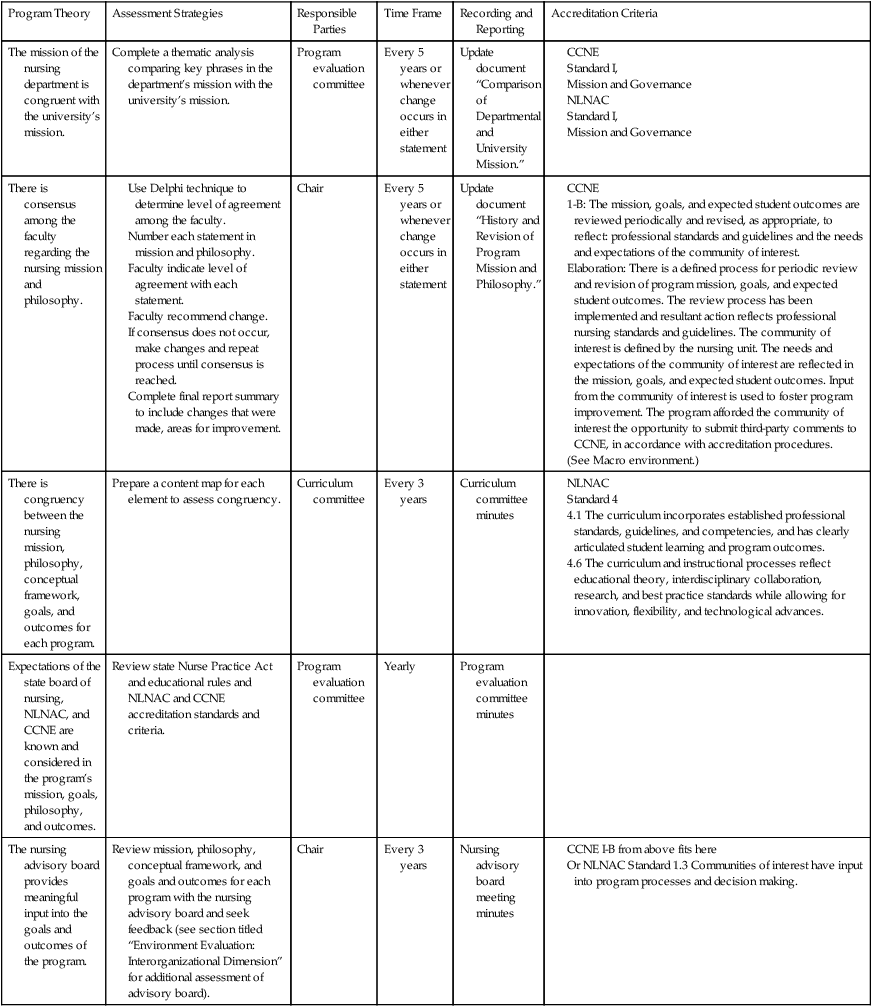

Marcia K. Sauter, PhD, RN, Nancy Nightingale Gillespie, PhD, RN and Amy Knepp, NP-C, MSN, RN The purpose of this chapter is to provide information on how to conduct comprehensive evaluation of nursing education programs. A brief history of program evaluation and examples of models for program evaluation will be followed by a description of a theory-driven approach to program evaluation, which has served as a framework for the evaluation of nursing education programs at a private university since 2000. The evaluation plan was originally adapted from Chen’s (1990) theory-driven model for program evaluation, which provides a mechanism for evaluating all program elements, for determining the causal relationships between program elements, for determining program effectiveness, and for identifying strategies to improve program quality. The evaluation plan has demonstrated long-term sustainability and has been easily adapted to changes in accreditation requirements. The evaluation plan has been refined during the past decade while maintaining the overall framework. A nursing education program is any academic program in a postsecondary institution leading to initial licensure or advanced preparation in nursing. Program evaluation is systematic assessment of all components of a program through the application of evaluation approaches, techniques, and knowledge in order to improve the planning, implementation, and effectiveness of programs (Chen, 2005). Program evaluation theory is a framework that guides the practice of program evaluation. A program evaluation plan is a document that serves as the blueprint for the evaluation of a specific program. Program theory is a set of assumptions that describes the elements of a program and their causal relationships. The purpose of program evaluation is to improve program effectiveness and demonstrate accountability. Evaluation may be developmental, designed to provide direction for the development and implementation of a program, or outcome-oriented, designed to judge the merit of the total program being evaluated. The focus of program evaluation is dependent on the stage of program implementation, beginning with program planning, through early implementation, and ending in mature program implementation (Chen, 2005). The more advanced a program is in its implementation, the more complex becomes the program evaluation. Specific purposes of program evaluation are as follows: 1. To determine how various elements of the program interact and influence program effectiveness 2. To determine the extent to which the mission, goals, and outcomes of the program are realized 3. To determine whether the program has been implemented as planned 4. To provide a rationale for decision making that leads to improved program effectiveness 5. To identify efficient use of resources that are needed to improve program quality Nursing programs have historically been too dependent on accreditation processes to guide program evaluation efforts (Ingersoll & Sauter, 1998). Some nursing programs do not fully engage in program evaluation until preparation of the self-study for an accreditation site visit has begun. To fulfill its purposes, program evaluation must be a continuous activity. Program evaluation built solely around accreditation criteria may lack examination of some important elements or understanding of the relationship between elements that influences program success. Nevertheless, building the assessment indicators identified by these bodies into the evaluation process ensures ongoing attention to state and national standards of excellence. The earliest approaches to educational program evaluation were based on Ralph Tyler’s (1949) behavioral objective model, which focused on whether learning experiences produced the desired educational outcomes. Tyler’s behavioral objective model was a simple, linear approach that began with defining learning objectives, developing measuring tools, and then measuring student performance to determine whether objectives had been met. Because evaluation occurred at the end of the learning experience, Tyler’s approach was primarily summative. Formative evaluation, which includes testing and revising curriculum components during the development and implementation of educational programs, became popular during the 1960s. This trend continued into the 1970s, when the Phi Delta Kappa National Study Committee on Evaluation concluded that meaningful educational evaluation was rare and encouraged educational institutions to continue formative evaluation by focusing on the process of program implementation (Stufflebeam, 1983). Outcomes assessment became the focus of educational evaluation in the 1980s. In 1984 the National Institute of Education Study Group on the Conditions of Excellence in American Postsecondary Education endorsed outcomes assessment as an essential strategy for improving the quality of education in postsecondary institutions (Ewell, 1985). By the mid-1980s numerous state legislatures began mandating outcomes assessment for public postsecondary institutions (Halpern, 1987) and the regional accrediting agencies began mandating outcomes assessment in their accreditation criteria (Ewell, 1985). Although the focus on outcomes assessment was growing rapidly, initial efforts at implementing outcomes assessment were not successful because educators experienced difficulty in developing appropriate methods for performing outcomes assessment and in obtaining adequate organizational support to implement assessment (Terenzini, 1989). The focus on outcomes assessment led some institutions to confuse outcomes assessment with comprehensive program evaluation. Nursing educators were also influenced by the outcomes assessment movement. Publications from the National League for Nursing (NLN) called for measurement of student outcomes (Waltz, 1988) and described measurement tools for assessing educational outcomes (Waltz & Miller, 1988). The Wingspread Group on Higher Education (1993) challenged providers of higher education to use outcomes assessment to improve teaching and learning. Nevertheless, outcomes assessment was not the final solution to improving program quality. Many postsecondary institutions continued to struggle with outcomes assessment, and those that were able to implement it were often unable to identify any academic improvements as a result of the assessment program (Tucker, 1995). Toward the end of the decade, approaches to organizational effectiveness, especially Deming’s continuous quality improvement model, began to influence a more comprehensive approach to program evaluation (Freed, Klugman, & Fife, 1997). As a result of the growing emphasis on program evaluation in the 1980s and 1990s, university programs were developed to prepare individuals in program evaluation (Shadish, Cook, & Leviton, 1991). As program evaluation became a distinct field of study, theories were developed to guide the practice of evaluation. Some of these theories include Borich and Jemelka’s (1982) systems theory; Stufflebeam’s context, input, process, and product (CIPP) model (1983); Guba and Lincoln’s fourth-generation evaluation framework (1989); Patton’s qualitative evaluation model (1990); Chen’s theory-driven model (1990); Veney and Kaluzny’s cybernetic decision model (1991); and Rossi and Freeman’s social research approach (1993). Perhaps because of the nursing profession’s emphasis on use of theory to guide practice, the need for program evaluation theory to guide evaluation practices in nursing education was identified in the nursing literature as early as 1978. Friesner (1978) reviewed five evaluation models: (1) Tyler’s behavioral objective model, (2) the NLN accreditation model, (3) Stufflebeam’s CIPP model, (4) Scriven’s goal-free evaluation model, and (5) Provus’s discrepancy evaluation. Friesner (1978) concluded that no single model could effectively guide the evaluation of nursing education and recommends that nursing educators blend elements from one or more of the models. In the early 1990s several articles about program evaluation theory appeared in the nursing literature. Watson and Herbener (1990) reviewed Provus’s discrepancy model, Scriven’s goal-free evaluation model, Stakes’ countenance model, Staropolia and Waltz’s decision model, and Stufflebeam’s CIPP model. These authors concluded that any of these models could be useful and recommended that nursing educators choose a model that best fits their needs. In contrast, Sarnecky (1990) explicitly recommended Guba and Lincoln’s (1989) responsiveness model after comparing it with Tyler’s behavioral objective model, Stake’s countenance model, Provus’s discrepancy model, and Stufflebeam’s CIPP model. Sarnecky believed that the other models did not adequately address the plurality of values among stakeholders and the importance of stakeholder involvement. Bevil (1991) proposed a theoretical framework she adapted from several evaluation theories. Ingersoll (1996) reviewed Borich and Jemelka’s systems approach, McClintock’s conceptual mapping approach, and Chen’s theory-driven model. Addressing issues about the reliability and validity of assessment activities, Ingersoll recommended that program evaluation be viewed as evaluation research and that program evaluation theory be used to guide the development and implementation of program evaluation. Ingersoll and Sauter (1998) reviewed Guba and Lincoln’s fourth-generation evaluation, Scriven’s goal-free approach, Norman and Lutenbacher’s theory of systems improvement, Rossi and Freeman’s social science approach, and Chen’s theory-driven model. The authors suggested that Rossi and Freeman’s model and Chen’s model had the most potential for guiding the evaluation of nursing education programs. Ingersoll and Sauter also expressed concern that nursing faculty commonly use accreditation criteria to form the framework for evaluation of nursing education programs. They recommended that program evaluation theory serve this purpose. Ingersoll and Sauter (1998) presented an evaluation plan developed from Chen’s theory-driven model that incorporated the NLNAC’s criteria for baccalaureate programs. Sauter (2000) surveyed all baccalaureate nursing programs in the United States to determine how they develop, implement, and revise their program evaluation plans. Few nursing programs reported using program evaluation theory to guide program evaluation. However, those educators that did use program evaluation theory were more satisfied with the effectiveness of their evaluation practices. In the past decade most of the nursing literature related to program evaluation has focused on specific elements of program evaluation, rather than on comprehensive evaluation. Only one article reported a theory-based approach to program evaluation. In 2006 Suhayda and Miller reported on the use of Stufflebeam’s CIPP model in providing a framework for comprehensive program evaluation that would serve undergraduate and graduate nursing programs. Program evaluation theories are either method-oriented or theory-driven, depending on their underlying assumptions, preferred methodology, and general focus. Method-oriented theories emphasize methods for performing evaluation, whereas theory-driven approaches emphasize the theoretical framework for developing and implementing evaluation. The more popular approaches have been method-oriented (Chen, 1990; Shadish et al., 1991). An example of a quantitative method-oriented program evaluation theory is Rossi and Freeman’s (1993) social science model. These authors believe that the use of experimental research methods will produce the most effective program evaluation. The advantage of this approach is that measurement techniques must be reliable and valid, even if experimental design is not used to conduct the evaluation. One of the major limitations of this approach is that the focus on methodology may divert evaluators from other issues, such as recognizing the importance of stakeholder perspective. In addition, experimental designs are often difficult to apply to some aspects of educational evaluation. An example of a qualitative method-oriented program evaluation theory is Guba and Lincoln’s (1989) fourth-generation evaluation. Guba and Lincoln advocate naturalistic methods for program evaluation. A special focus of their approach is the emphasis they place on integrating multiple stakeholders’ viewpoints into program evaluation. A major advantage of their approach is that using qualitative methodology allows evaluators to achieve a greater depth of understanding of program strengths and limitations within a specific context. The approach is limited because it tends to overlook outcomes assessment, which usually requires more quantitative methodology. Theory-driven approaches to program evaluation begin with the development of program theory. Program theory is the framework that describes the elements of the program and explains the relationships between and among elements. When this approach is used, program evaluation is intended to test whether the program theory is correct and whether it has been implemented correctly. If the program is not successful in achieving outcomes, a theory-driven approach allows the evaluator to determine whether the program’s failure is due to flaws in the program theory or failure to implement the program correctly. The theory-driven approach often calls for a variety of research methods because evaluators choose the methodology that is best suited to answering the evaluation questions (Chen, 1990). Chen’s (1990) theory-driven model is one of the most comprehensive models for program evaluation. Although the model was intended for evaluation of social service programs, it is adaptable to educational programs. A brief overview of Chen’s model is included here. The remainder of the chapter describes a nursing education program evaluation plan that was developed from Chen’s theory-driven model. The evaluation plan has been in continuous use since 2000 and has been applied to undergraduate and graduate nursing programs. For a more detailed description of how the evaluation plan was created from Chen’s original theory-driven model, see Sauter, Johnson, and Gillespie (2009). Chen (1990) defines program theory as a framework that identifies the elements of the program, provides the rationale for interventions, and describes the causal linkages between the elements, interventions, and outcomes. According to Chen, program theory is needed to determine desired goals, what ought to be done to achieve desired goals, how actions should be organized, and what outcome criteria should be investigated. Program evaluation is the systematic collection of empirical evidence to assess congruency between the program’s design and implementation and to test the program theory. Through this systematic collection of evidence, program planners can develop and refine program structure and operations, understand and strengthen program effectiveness and utility, and facilitate policy decision making (Chen, 1990). The following section describes a program evaluation plan for nursing education programs adapted from Chen’s (1990) theory-driven model. The components of the evaluation plan are organized into six evaluation types, which were modified and adapted from Chen’s model. Table 28-1 lists the evaluation types defined by Chen, provides a brief description of the elements of the evaluation type, and demonstrates how Chen’s model was adapted to the evaluation of nursing education programs. TABLE 28-1 Comparison of Chen’s Theory-Driven Model for Program Evaluation and a Model for Nursing Education There should be consensus among the faculty regarding the nursing school’s mission and philosophy. A modified Delphi approach to determine the level of agreement among the faculty for each statement in the mission and philosophy is a useful strategy. The Delphi approach is useful for both the development and the evaluation of belief statements (philosophy). This approach seeks consensus without the need for frequent face-to-face dialogue in a manner that protects the anonymity of participants. In this method, questionnaires that list proposition statements about each of the content elements of the belief statement are distributed. A common breakdown of Delphi responses is a five-point range from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” so that respondents can indicate their level of support for each proposition. Respondents are provided with feedback about the responses after the first round of questionnaire distribution, and a second round may occur to determine the intensity of agreement or disagreement with the group median responses (Uhl, 1991). After several rounds with interim reports and analyses, it is usually possible to identify areas of consensus, areas of disagreement so strong that further discourse is unlikely to lead to consensus, and areas in which further discussion is warranted. In the evaluation of an established belief statement, the same process will provide data about which propositions continue to be supported, which no longer garner support, and which need to be openly debated (Uhl, 1991). The result provides a consensus list of propositions that either supports the belief statement as it is or suggests areas for revision. Chapter 7 provides further information on development of mission and philosophy. All accrediting bodies have expectations about mission, philosophy, program goals, and outcomes. The NLNAC (2008) defines Standard I, Mission and Governance, in which it requires that the nursing program provide clear statements of mission, philosophy, and purposes. In addition, the NLNAC has indicated both required and optional outcomes that nursing programs must measure over time to provide trend data about student learning. For example, the required outcomes in the criteria for baccalaureate and higher degree programs are graduation rates, job placement rates, licensure and certification pass rates, and program satisfaction (NLNAC, 2008). The CCNE (2010) also includes in Standard I, Mission and Governance, expectations regarding congruency of the program’s mission, goals, and outcomes with those of the parent institution, professional nursing standards, and the needs of the community of interest. Professional organizations include the American Nurses Association (ANA), American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN), and National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties (NONPF). Program goals and outcomes in baccalaureate degree programs should be congruent with the ANA’s Standards of Practice (ANA, 2010) and the AACN’s Essentials of Baccalaureate Education for Professional Nursing Practice (AACN, 2008a). The same consideration should be given to the AACN’s Essentials of Master’s Education of Advanced Practice Nursing (AACN, 1996) and the Criteria for Evaluation of Nurse Practitioner Programs (NONPF, 2008) for master’s degree programs. The AACN (2006) also provides indicators of quality in doctoral programs in nursing in Essentials of Doctoral Education for Advanced Nursing Practice. Box 28-1 lists the theoretical elements for mission and goal evaluation. Table 28-2 provides a sample evaluation plan for mission and goal evaluation applied to a nursing education program. This sample demonstrates how all elements of the program evaluation plan may be articulated, including the program’s theoretical elements, assessment activities, responsible parties, time frames, and related accreditation criteria. For the remaining evaluation components presented in this chapter, only examples of theoretical elements and methods for gathering and analyzing assessment data relevant to the identified theoretical elements are provided. The theoretical elements and assessment strategies that are suggested here are not all-inclusive but may assist nursing faculty in further development of their own program theory and program evaluation plan. TABLE 28-2 AACN, American Association of Colleges of Nursing; ANA, American Nurses Association; BSN, bachelor of science in nursing; CCNE, Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education; DNP, doctorate in nursing practice; NLNAC, National League for Nursing Accrediting Commission. Curriculum must be appropriately organized to move learners along a continuum from program entry to program completion. The principle of vertical organization guides both the planning and the evaluation of the curriculum. This principle provides the rationale for the sequencing of curricular content elements (Schwab, 1973). For example, nursing faculty often use depth and complexity as sequencing guides; that is, given content areas may occur in subsequent levels of the curriculum at a level of greater depth and complexity. This is supported by the work of Gagné (1977), who developed a hierarchical theory of instruction based on the premise that knowledge is acquired by proceeding from data and concepts to principles and constructs. In evaluation of the curriculum, faculty must assess for increasing depth and complexity to determine whether the sequencing was useful to learning and progressed to the desired outcomes. Determination of whether course and level objectives demonstrate sequential learning across the curriculum can be used as a test of vertical organization. The analysis can be performed with Bloom’s (1956) taxonomy as a guide for determining whether objectives follow a path of increasing complexity. The principle of internal consistency is important to the evaluation of the curriculum. The curriculum design is a carefully conceived plan that takes its shape from what its creators believe about people and their education. The intellectual test of a curriculum design is the extent to which the elements fit together. Four elements should be congruent: objectives, subject matter taught, learning activities used, and outcomes (Doll, 1992). Evaluation efforts should include examination of the extent to which the objectives and outcomes are linked to the mission and belief statements. Program objectives should be tracked to level and course objectives. One method of assessing internal consistency is through the use of a curriculum matrix (Heinrich, Karner, Gaglione, & Lambert, 2002). The matrix is a visual representation that lists all nursing courses and shows the placement of major concepts flowing from the program philosophy and conceptual framework. Another approach to assessment of internal consistency is through a curriculum audit (Seager & Anema, 2003). Similar to a curriculum matrix, the curriculum audit provides a visual representation that matches competencies to courses and learning activities. The principle of linear congruence, sometimes called horizontal organization, assists faculty in determining which courses should precede and follow others and which should be concurrent (Schwab, 1973). The concept of sequencing follows the principle of moderate novelty in that new information and experiences should not be presented until existing knowledge has been assimilated (Rabinowitz & Schubert, 1991). An appropriate question is: “What entry skills and knowledge does the student need as a condition of subsequent knowledge and experiences?” How faculty answer this question will determine curriculum design and implementation. The evaluation question would address the extent to which students have the entry-level skills needed to progress sequentially in the curriculum. This is a critical question in light of the changing profile of students entering college-level programs. It is often difficult to determine which prerequisite skills should be required for entry and which should be acquired concurrently. Computer skills are a good example. Students enter programs with varying ability in using computers. It is necessary to determine the prerequisite skills needed and the sequence in which advanced skills should be acquired during the program of learning. Individual courses are reviewed to determine whether they have met the tests of internal consistency, linear congruence, and vertical organization. A triangulation approach to course evaluation is useful. This approach uses data from three sources—faculty, students, and materials review—to identify strengths and areas for change (DiFlorio, Duncan, Martin, & Meddlemiss, 1989). Each course is evaluated to determine whether content elements, learning activities, evaluation measures, and learner outcomes are consistent with the objectives of the course and the obligations of the course in terms of its placement in the total curriculum. Faculty should clearly articulate the sequential levels of each expected ability to determine what teaching and learning strategies are needed to move the student to progressive levels of ability and to establish the criteria for determining that each stage of development has been achieved. This need is important in relation not only to abilities specific to the discipline or major but also to the transferable skills acquired in the general education component of the curriculum (Loacker & Mentkowski, 1993). Some faculty achieve this by creating content maps for each major thread or pervasive strand in the curriculum with related knowledge and skill elements. The content maps chart the obligation of each course in facilitating student progression to the expected program outcome. The maps also provide a guide for the evaluation of whether the elements were incorporated as planned. Angelo and Cross (1993) have developed a teaching goals inventory tool that is useful in individual course evaluation. The purpose is to assist faculty in identifying and clarifying their teaching goals by helping them to rank the relative importance of teaching goals in a given course. The construction of the teaching goals inventory began in 1986 and involved a complex process that included a literature review, several cycles of data collection and analysis, expert analysis, and field testing with hundreds of teachers (Angelo & Cross, 1993). In the process, Angelo and Cross developed a tool that clusters goals into higher-order thinking skills, basic academic success skills, discipline-specific knowledge and skills, liberal arts and academic values, work and career preparation, and personal development. This tool can assist the faculty in determining priorities in the selection of teaching and learning activities designed to advance the student toward the desired goals and in evaluating whether teaching goals and strategies are congruent with course objectives. Liberal education is fundamental to professional education. Expected outcomes for the liberal arts component of professional programs have received much attention in recent years (Association of American Colleges and Universities, 2002). Expected outcomes for today’s college students include effective communication skills; the use of quantitative and qualitative data in solving problems; and the ability to evaluate various types of information, work effectively within complex systems, manage change, and demonstrate judgment in the use of knowledge. In addition, students should demonstrate a commitment to civic engagement, an understanding of various cultures, and the ability to apply ethical reasoning. Nursing faculty should work collaboratively with faculty across disciplines to ensure that the general education curriculum supports the expectations of a twenty-first-century liberal education. External accrediting agencies have expectations about liberal education. The NLNAC (2008) states that no more than 60% of courses in associate degree curricula may be in the nursing major. The remainder of coursework should be in general education. The criteria for baccalaureate and higher-degree programs do not indicate a desired ratio. Box 28-2 provides a summary of the theoretical elements associated with curriculum evaluation. Evaluation of teaching effectiveness involves assessment of teaching strategies (including instructional materials), assessment of methods used to evaluate student performance, and assessment of student learning. Teaching strategies are effective when students are actively engaged, when strategies assist students to achieve course objectives, and when strategies provide opportunities for students to use prior knowledge in building new knowledge. Teaching effectiveness improves when teaching strategies are modified on the basis of evaluation data. See Chapter 11 for information on designing teaching strategies and student learning activities. To demonstrate and document teaching effectiveness, faculty need multiple evaluation methods (Johnson & Ryan, 2000). Evaluation methods may include student feedback about teaching effectiveness obtained through course evaluations and focus group discussions, feedback provided through peer review, formal testing of teaching strategies, and assessment of student learning. Although focus groups have been used extensively in marketing and social research, they have the potential to serve as powerful tools for program evaluation (Loriz & Foster, 2001). A focus group discussion with students can provide a qualitative assessment of teaching effectiveness. Focus groups provide an opportunity to obtain insights and to hear student perspectives that may not be discovered through formal course evaluations. The focus group leader should be an impartial individual with the skill to conduct the session. The leader should clearly state the purpose of the session, ensure confidentiality, provide clear guidelines about the type of information being sought, and explain how information will be used (Palomba & Banta, 1999). The reliability and validity of information obtained from a focus group discussion is enhanced when the approach is conducted as research with a purposeful design and careful choice of participants (Kevern & Webb, 2001). Although classroom observation has been used as a technique for the peer review of teaching for a number of years, the reliability and validity of this method has been suspect. The validity and reliability of classroom observation as an evaluation tool is increased by (1) including multiple visits and multiple visitors, (2) establishing clear criteria in advance of the observation, (3) ensuring that participants agree about the appropriateness and fairness of the assessment instruments and the process, and (4) preparing faculty to conduct observations (Seldin, 1980; Weimer, Kerns, & Parrett, 1988). Before classroom teaching visits are made, the students should be advised of the visit and should be assured that they are not the focus of the observation. Peer reviewers should meet with the faculty member before the visit and review the goals of the session, what has preceded and what will follow the session, planned teaching methods, assignments made for the session, and an indication of how this class fits into the total program. This provides a clear image for the visitors and establishes a beginning rapport. Some faculty have particular goals for growth that can be shared at this time as areas for careful observation and comment. Finally, a postvisit interview should be conducted to review the observation and to identify strengths and areas for growth. This may include consultation regarding strategies for growth with the scheduling of a return visit at a later date. Many visitors interview the students briefly after the visit to determine their reaction to the class and to ascertain whether this was a typical class rather than a special, staged event. Unless there is a designated visiting team, the faculty member to be visited is usually able to make selections or at least suggestions about the visitors who will make the observation. Peer visits to clinical teaching sessions should follow the same general approach as classroom visits, although specific criteria for observation will be established to meet the unique attributes of clinical teaching and learning. An additional requirement is that the visitor be familiar with clinical practice expectations in the area to be visited. In the review of textbooks for their appropriateness for a given course, multiple elements may be considered. The readability of a text relates to the extent to which the reading demands of the textbook match the reading abilities of the students. This assumes that the faculty member has a profile of student reading scores from preadmission testing. Readability of a textbook is usually based on measures of word difficulty and sentence complexity. Other issues of concern include the use of visual aids; cultural and sexual biases; scope and depth of content coverage; and size, cost, and accuracy of the data contained within the text (Armbruster & Anderson, 1991). Another factor of importance is the structure of the textbook. This element relates to the organization and presentation of material in a logical manner that increases the likelihood of the reader’s understanding of the content and ability to apply the content to practice. A review should determine the ratio of important and unimportant material and the extent to which important concepts are articulated, clarified, and exemplified. Do the authors relate intervening ideas to the main thesis of a chapter and clarify the relationships between and among central concepts (Armbruster & Anderson, 1991)? The ease with which information can be located in the index is important so that students can use the book as a reference. Because of the high cost of textbooks, it is useful to consider whether the textbook will be a good reference for other classes in the curriculum. A review of a textbook must also include consideration of whether the content has supported student learning. When student papers or other creative products are used for evaluation purposes, it is common to review a sample of these papers or products that the teacher has judged to be weak, average, and above average to provide a clearer view of expectations and how the students have met those expectations. This review provides an opportunity to demonstrate student outcomes. If a faculty member wants to retain copies of student papers and creative works to demonstrate outcomes, he or she should obtain informed consent from the students. Accrediting bodies often wish to see samples of student work, and faculty may use them to demonstrate learning outcomes for purposes of their own evaluation. Each student’s identity should be protected and consent should be obtained. The review of teaching and learning aids depends on the organization and use of these materials. The organization may be highly structured in that all are expected to use certain materials in certain situations or sequences, or materials may be resources available to faculty and students for use at their discretion according to the outcomes they wish to achieve (Rogers, 1983). Students may be expected to search for and locate materials, to create materials to facilitate their learning, or simply to use the materials provided in a prescribed manner. The emphasis will determine whether evaluation questions related to materials are based on variety, creativity, and availability or whether the materials have been used as intended. Regardless of the overall emphasis, teaching and learning materials should be evaluated for efficiency and cost-effectiveness. Efficiency can be evaluated by determining whether the time demands and effort required to use the materials are worth the outcomes achieved. Cost-effectiveness can be determined by considering whether the costs of the materials justify the outcomes.

Educational program evaluation

Definition of terms

Purposes and benefits of program evaluation

Relationship of program evaluation to accreditation

Historical perspective

Program evaluation theories

Theory-driven program evaluation

Adapting chen’s theory-driven model to program evaluation for nursing education

Chen’s Evaluation Types

Components for Evaluation of Nursing Education Programs

Normative outcome evaluation

Mission and goal evaluation

Normative treatment evaluation

Implementation Environment Evaluation

Environment Evaluation

Participant dimension

Student dimension

Implementer dimension

Faculty dimension

Delivery mode dimension

Delivery mode dimension

Implementing organization dimension

Organization dimension

Interorganizational relationship dimension

Interorganizational relationship dimension

Micro context dimension

Micro context dimension

Macro context dimension

Macro context dimension

Impact evaluation

Outcomes assessment

Intervening mechanism evaluation

Intervening mechanism evaluation

Generalization evaluation

Generalization evaluation

Mission and goal evaluation

Curriculum evaluation

Evaluation of curriculum organization

Course evaluation

Evaluation of support courses and the liberal education foundation

Evaluation of teaching effectiveness

Student evaluation of teaching strategies

Peer review of teaching strategies

Evaluation of teaching and learning materials

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Educational program evaluation

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access