CHAPTER 7 Education for health

In Chapter 7 we move along the continuum of health promotion approaches outlined in Chapter 1 and begin to examine the behavioural approaches to health promotion. There is a range of behaviour change approaches, including education strategies, which will be the focus of this chapter. The importance of these strategies is recognised in the UN Declaration of Human Rights and the WHO Primary Health Care Declaration of Alma-Ata; they fit well with the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion’s action area of developing personal skills.

DEFINING HEALTH EDUCATION

Health education has been defined as ‘. . . any combination of learning experiences designed to facilitate voluntary actions conducive to health’ (Green & Kreuter 1999). There are two important elements in this definition. The first is that health education entails much more than the formal ‘teaching’ sessions that we may traditionally expect to undertake in this role. This point is emphasised by Bedworth and Bedworth (1992: 7) in their definition of health education:

RATIONALE FOR HEALTH EDUCATION

Health literacy

Results indicated that health literacy is a social determinant of health. The most vulnerable members of Australian society in terms of educational attainment, labour force participation and skill level, parental education, social or geographic isolation, and cultural minority status also had the lowest health literacy. The results are comparable to those from Canada (ABS 2006b).

CRITIQUE OF HEALTH EDUCATION BEHAVIOUR CHANGE APPROACHES

The first reason to critique behaviour change approaches relates to the concept of ‘victim blaming’, dealt with in some detail in Chapter 2. When individuals are expected to take responsibility protecting their health and preventing factors and behaviours that make illnesses more likely, there is potential to ‘blame’ those who are unable to make these changes for their ‘failure’. The inference here is that because a person knows that a behaviour, such as smoking, is not good for their health they will be able to change this behaviour, and it is their own fault if they do not. The implication of these so-called ‘lifestyle choices’ is that people have the necessary knowledge, social support, money and motivation to make the changes and sustain them. It takes no account of the challenges of addiction, or the social circumstances that affect the choices people are able to make.

The second element of criticism is that expenditure on health education for behaviour change diverts attention from the structural causes of disease in social policy. Health education provides a political excuse for avoiding decisions about implementation of broad long-term healthy public policies. Behaviour change approaches can be more expediently implemented during the course of one political term and they are more readily evaluated than the social change and community building strategies that we outlined in Chapters 3 and 4.

VALUES IN HEALTH EDUCATION

Chapter 2 reviewed several key values in health promotion, many of which have particular relevance to health education. In particular, the attitudes of health workers towards community members, the presence or absence of victim blaming or labelling, and whether health workers see education as an opportunity for encouraging compliance as a form of ‘power over’, or as a means of empowerment, have a major impact on both the way in which education occurs and the likely learning outcomes of that education.

Health workers using a Primary Health Care approach work in partnership with community members, recognising the expertise that community members bring to the learning process. They recognise education as an enabling strategy rather than one to encourage compliance with others’ wishes. For this to occur the focus is on creating a learning partnership in which learning community members decide what knowledge and skills they need in order to help change the things in their living environment which put their health at risk. Because of the central role of these values in health education, readers are encouraged to review Chapter 2 if they are not familiar with them.

EDUCATION APPROACHES TO ADDRESS THE SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH

Education for critical consciousness

1. reflecting upon aspects of their reality (e.g. problems of poor health, housing, etc.)

2. looking behind these immediate problems to their root causes

3. examining the implications and consequences of these issues, and finally;

4. developing a plan of action to deal with the problems collectively identified.

Before such a process can occur, however, health workers need to listen carefully to the needs articulated by community members and take the time to understand their problems as they see them (Wallerstein & Bernstein 1988: 382). They also need to observe the dynamics of the groups and individuals concerned to determine what sense of belonging or community exists. Some sense of community or group belonging seems to be important for the conscientisation process to work effectively (Minkler & Cox 1980: 320). It is for this reason that education for critical consciousness often goes hand in hand with community development.

Health education planning frameworks

By now you will be familiar with the continuum of health promotion approaches, first presented in Chapter 1. Other chapters in this text present approaches to health promotion, according to the particular focus of the activity. Community development and health policy approaches are most appropriate to address the social determinants of health, because they are most likely to lead to sustainable changes in the social context of people’s lives. However, as we have argued above, there are times when a different focus is necessary and the aim of the health worker becomes one of enhancing the health literacy of individuals and groups. When planning health education strategies for individuals and groups it is useful to ‘map’ the activity, to ensure it meets the educational needs of the group, and that it enables them to make informed decisions affecting their health.

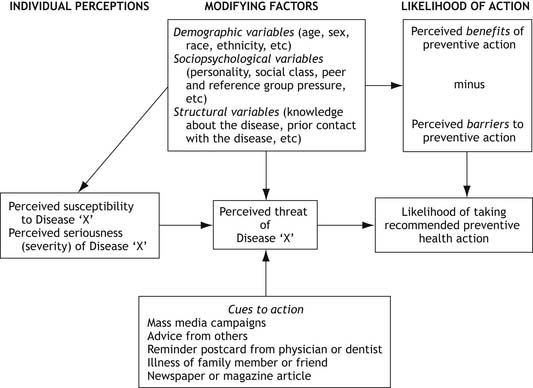

The Health Belief Model is one health educational planning model (see Figure 7.1). While the Health Belief Model has been presented in some detail here, because it is widely used and has been extensively validated, it is by no means the only useful model for health education planning. A number of other planning models are widely used in health behaviour approaches, such as the Transtheoretical (Stages of Change) Model (Prochaska & DiClimente 1984) and the Theory of Reasoned Action and Planned Behaviour (Ajzen & Fishbein 1980). Nutbeam and Harris (2004) and Naidoo & Wills (2000) both provide very useful overviews of a range of commonly used planning models.

The Health Belief Model is based on social learning theory (Nutbeam & Harris 2004) and was developed to provide a framework for explaining why some people take action to avoid a specific illness or condition and others do not. The model can be used to suggest interventions that would make some individuals more likely to engage in health protective behaviours. The Health Belief Model is useful when planning health protective activities for particular groups in relation to a specific condition (Becker et al 1974), because it guides the health educator to consider the social context of people’s health behaviours. It is not designed for use in social change movements or community development approaches. Nutbeam and Harris (2004: xii) caution that ‘unless behavioural theories are put into the broader context in which the individual is living, many factors that influence health will remain unexplained’ or un-addressed. This is an important point to consider when choosing which model best applies in health education planning.

The Health Belief Model predicts that an individual is likely to take action based on the interaction between four conceptual areas. Refer to the Figure 7.1 as you read the description.

1. The individual’s perceptions about the seriousness of a given condition. Perceived susceptibility is a person’s estimate of their probability of encountering the health condition. This estimate is dependent on their knowledge, and thus it is an important function of health education to provide accessible, reliable information as required.

2. The individual’s perceptions about the severity of the condition. Perceived seriousness relates to the difficulties that individuals believe a given health condition would create. These difficulties may include the implications for work, family and social life, so the emotional response of an individual to a condition is significant here. It is only when the perceived seriousness is manageable — neither too low to be insignificant, nor too challenging or frightening to contemplate — that a person can consider a change in behaviour. Thus, launching into a health education message when a person is overwhelmed by other issues and needs support is not only unethical but also ineffective.

3. The individual’s perceptions about the benefits of taking action to avoid or detect the condition. The perceived benefits of recommended preventive actions are important determinants of health protective behaviours. For example, women who believe Pap smears can detect cancer early, and this results in a good prognosis, are more likely to take part in screening.

4. Perceived barriers may be personal — such as the embarrassment or unpleasantness of having the procedure — or they may be social — such as cost, inconvenience or the frequency of the desired behaviours that are required, and the extent of life changes. These barriers give important guidelines for health workers on planning their sessions according to the needs and characteristics of their audience.

TEACHING AND LEARNING EDUCATION THEORY

It is clear that the assumptions inherent in this diagram fail to encompass the complexity of what is required to adopt a new health behaviour. Is there accurate or inaccurate information about the risks to health? What factors influence the value a person places on the desired change — peer or social pressure, media? What factors enhance or inhibit the desire for change — costs, family social circumstance?

The teaching—learning process

1. Teaching–learning is a process, not a product — that is, new information and skills are not the only goals. How that learning occurs is equally important and may contribute greatly to the learning process.

2. The teaching–learning process occurs between people who all bring their own expertise to the situation, whether it be the expertise of personal and collective experiences or the more theoretical expertise carried by health workers.

3. The teaching–learning process needs to be built on effective communication and mutual respect.

Facilitating the teaching—learning process

Adult learning principles

allow people to direct the learning process

allow people to direct the learning process

get to know the people’s perspective

get to know the people’s perspective

be aware of the context of people’s lives

be aware of the context of people’s lives

build on what people already know

build on what people already know

planned achievements need to be realistic

planned achievements need to be realistic

take account of all levels of learning

take account of all levels of learning

Each will be explored briefly in the following section.

Allow people to direct the learning process

Individual or group-controlled learning is most likely to occur if people themselves set the goals of learning. Helping people clarify just what it is they want to learn is therefore an important part of the education process. Active participation can also be encouraged by maximising interactive teaching techniques and activities, rather than taking an ‘empty vessel’ approach and ‘filling’ passive recipients with information. People need to be able to have their say, use their initiative, experiment and find out what works for them. Structuring education so that these things are possible is therefore another priority for health workers who are eager to facilitate learning. Which interactive techniques and activities are appropriate will vary depending on the situation, the people involved, and on whether it is education for individual change or education for social change. Commonly used interactive activities include debating contentious issues, using structured group activities, planning action to address a problem and practising the action required (whether that be drafting a letter to a local councillor, role-playing the negotiation between work colleagues about smoking in the workplace, or preparing a low-fat meal). It is important to point out, though, that interactive techniques do not by themselves ensure interactive learning, nor is interactive learning precluded by the use of what are traditionally regarded as non-interactive techniques, such as lectures. Rather, it is how teaching techniques are used that ultimately determines the extent and success of interactive learning. Once again, emphasis should focus on how the health worker and learners use the teaching techniques, rather than solely on which techniques are used.

Build on what people already know

Ensure that education starts from the point where it is easiest for people to begin to learn; their active participation in planning learning opportunities will assist. This builds on what people already know, providing new material in a format and at a pace that is appropriate to the learner or learners. Finding out what people know in a way that does not leave them feeling vulnerable is an important skill here. Intersperse questions throughout teaching sessions to make the links to prior knowledge and to assess the level of understanding. For example, ‘Can you tell me what you have heard about osteoporosis?’ provides people with more scope to express ideas they are unsure of than asking people what they ‘know’ about the topic. Treat mistakes as occasions for learning.

Facilitating adult learning

When working with any audience, including adult learners, it is important to value and respect the wisdom that participants bring to the learning environment. In addition, we must recognise that many learners are challenged and unnerved by being placed in a learning setting, especially if they are made to feel inferior. The following points provide guidance as to how the facilitator can manage the environment positively.

Be a good listener. ‘Hear’ the participants, value their contributions and make links between their contributions and the key themes around the topic.

Be a good listener. ‘Hear’ the participants, value their contributions and make links between their contributions and the key themes around the topic.

Communicate effectively with warmth, respect and encouragement. A superior attitude to participants will make them less likely to contribute.

Communicate effectively with warmth, respect and encouragement. A superior attitude to participants will make them less likely to contribute.

Be able to clarify points of difficulty or confusion. While a good knowledge of the topic is useful, the facilitator should not expect to know ‘everything’. Knowledge gaps can be treated as opportunities for exploration, without losing the respect of participants. The participants will know very early if the facilitator is trying to make them believe they have more knowledge than them.

Be able to clarify points of difficulty or confusion. While a good knowledge of the topic is useful, the facilitator should not expect to know ‘everything’. Knowledge gaps can be treated as opportunities for exploration, without losing the respect of participants. The participants will know very early if the facilitator is trying to make them believe they have more knowledge than them.

Be flexible to adjust to the needs of the learners. The pace and detail in a theme will vary according to the prior learning, including life experiences of the participants, and their need for the information at the time.

Be flexible to adjust to the needs of the learners. The pace and detail in a theme will vary according to the prior learning, including life experiences of the participants, and their need for the information at the time.

Don’t ‘own’ the topic. This is a sign of a confident and mature facilitator. One of the key skills health workers need to learn is to relinquish ‘control’ of the group, and allow it to be led by the participants. A facilitator may need to ‘steer’ the discussion to ensure that topics the group decides are important, are covered.

Don’t ‘own’ the topic. This is a sign of a confident and mature facilitator. One of the key skills health workers need to learn is to relinquish ‘control’ of the group, and allow it to be led by the participants. A facilitator may need to ‘steer’ the discussion to ensure that topics the group decides are important, are covered.

COGNITIVE, AFFECTIVE AND PSYCHOMOTOR DOMAINS OF LEARNING

Domains of learning

Learning a new concept or skill may involve moving through progressive levels of understanding. Bloom (1964) developed a ‘taxonomy of educational objectives’. A taxonomy is a system of classification. Bloom argued that learning can be classified into three domains (cognitive, affective and psychomotor) according to the type of learning that is taking place. Each domain is further categorised according to the level or complexity of the concept that is being learned, progressing from the simple to the most complex. Classifying learning processes into these three domains serves to strengthen the understanding of the learning processes which are still relevant in a range of settings (Kiger 2004). The domains can be used as a framework for writing learning objectives, based on the adult learning principles presented earlier. As argued there, it is not appropriate to develop separate activities for learning knowledge (cognitive), attitudes (affective) and behaviour (psychomotor), because the concepts are interwoven. The domains are presented here in the sequence set out above as a simple linear statement. However they could just as easily represent learning by being presented in the opposite order.

Cognitive domain

The cognitive domain describes learning which relates to the recall and recognition of knowledge and the development of intellectual abilities. This is a hierarchical domain, in that each level of learning becomes more complex and builds on the learning processes of the prior level (Bloom 1964). The hierarchical arrangement with illustrative examples is set out in Box 7.1.

BOX 7.1 Taxonomy of cognitive learning domain

| Level 1 | Knowledge | Recall of facts, methods and procedures |

| Level 2 | Comprehension | Combining recall and understanding |

| Level 3 | Application | Using information in new specific and concrete situations |

| Level 4 | Analysis | Distinguishing components and understanding relationships between components |

| Level 5 | Synthesis | Putting the information into a unified whole |

| Level 6 | Evaluation | Judging the value of ideas, procedures and methods |

(Source: Derived from Bloom B S 1964 Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: the Classification of Educational Goals. Longman Group, London)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree