Educating Learners with Disabilities

Deborah L. Sopczyk

CHAPTER HIGHLIGHTS

Scope of the Problem

Models and Definitions

The Language of Disabilities

The Nurse Educator’s Roles and Responsibilities

Types of Disabilities

Sensory Deficits

Hearing Impairments

Visual Impairments

Learning Disabilities

Dyslexia

Auditory Processing Disorders

Dyscalculia

Developmental Disabilities

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

Intellectual Disabilities

Asperger Syndrome/Autism Spectrum Disorder

Mental Illness

Physical Disabilities

Traumatic Brain Injury

Memory Disorders

Communication Disorders

Aphasia

Dysarthria

Chronic Illness

The Family’s Role in Chronic Illness or Disability

Assistive Technologies

State of the Evidence

KEY TERMS

disability

people-first language

habilitation

rehabilitation

sensory disabilities

hearing impairment

visual impairment

learning disability

dyslexia

auditory processing disorder

dyscalculia

developmental disability

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

global aphasia

expressive aphasia

receptive aphasia

anomic aphasia

augmentative and alternative communication

dysarthria

assistive technology

OBJECTIVES

After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to

Compare and contrast various definitions of disability.

Describe the language that should be used when writing about, talking to, or talking about people with disabilities.

Describe the various teaching strategies that can be used when working with a client with a sensory disability.

Explain teaching strategies that can be used when working with a client who has a learning or developmental disability.

Describe ways in which the teaching-learning plan can be adapted when working with a client who has a physical or mental disability.

Enhance the teaching-learning process for someone with a communication disability.

Discuss the effects of a chronic illness on people and their families in the teaching-learning process.

Describe assistive technology and its application for people with disabilities.

Teaching others about health, wellness, disease, and its treatment and care is a critical and challenging role for the nurse working in any setting and with any population of individuals. However, the teaching-learning process is especially demanding when working with clients whose abilities to learn are challenged by sensory, cognitive, mental health, physical, and other types of disabilities that affect their capacities to see, hear, speak, understand, remember, or process information. The educational component of the practice of nursing becomes paramount in importance as the nurse’s efforts are directed toward assisting clients and their significant others to maintain already established patterns of living or to develop new ones to accommodate changes in health status or functional ability.

This chapter focuses on those clients whose sensory, cognitive, mental health, or physical conditions require nurses to adapt their approach to

client education to enable learning. Although the information presented here focuses specifically on client populations, the same principles of teaching and learning can be extrapolated to apply to other categories of learners. For example, the nurse educator, in the role of in-service educator, faculty member, or staff development coordinator, may use these strategies when teaching hospital personnel or nursing students who may have a physical or learning disability.

client education to enable learning. Although the information presented here focuses specifically on client populations, the same principles of teaching and learning can be extrapolated to apply to other categories of learners. For example, the nurse educator, in the role of in-service educator, faculty member, or staff development coordinator, may use these strategies when teaching hospital personnel or nursing students who may have a physical or learning disability.

This chapter provides an overview of a wide range of physical, mental health, and cognitive disabilities and other issues that affect the ways in which people learn. Included are the most common disabilities encountered by nurses, such as learning disabilities, mental illness, and stroke. Chronic illness is included because it is a situational issue that requires a change in the way the nurse approaches health education. This chapter also provides a summary of assessment, teaching, and evaluation strategies that nurse educators can use in designing and implementing teaching plans for this group of clients and their families.

SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM

Disability is a worldwide issue. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), more than 1 billion people throughout the world live with a condition that is classified as a disability. This number is expected to increase as populations age and the incidence of debilitating conditions such as diabetes, obesity, and cancer continues to grow (WHO, 2012).

Given these worldwide statistics, it is not surprising that a significant number of Americans live with a wide range of disabilities that affect them in a number of ways. In a recent report released by the U.S. Census Bureau (2012), nearly 60 million Americans (1 in 5) were estimated to have a disability, with almost half of these persons reporting a disability that was considered to be severe. According to Cornell University (2012), in 2011 almost 1 in 12 Americans aged 18-64 reported a disability severe enough to limit their ability to work.

Despite the statistics that imply disabilities are restricted to a certain percentage of the population, disabilities actually affect most people at some point in their lives. The aging process as well as the chronic and acute health conditions that affect almost everyone can cause temporary or permanent impairment in the functioning of people who were born without a disabling condition. As a consequence, nurses in all settings are likely to encounter clients who are facing the challenge of a functional impairment in themselves or in the family members they care for.

If the incidence of disabilities seems high, it is important to remember that not all disabilities are readily apparent. For example, among people with disabilities aged 15 and older, only 1.5% use a wheelchair, 0.02% are unable to have their speech understood, another 0.08% are unable to see, and 0.01% are unable to hear. By comparison, more than 4% of people with disabilities have a learning disability, 2% have a mental health problem, and almost 5% have a minor hearing or vision deficit—all disabilities that often remain hidden (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010).

Individuals with disabilities are more likely than people without disabilities to suffer health disparities and are less likely to receive preventive health services (Reichard, Stolzle, & Fox, 2011). For example, a review of the disabilities research conducted between 1990 and 2005 revealed disparities existed for women with disabilities in five categories—incidence of chronic disease, cancer, mental health and substance abuse, preventive screenings, and health-promoting behavior (Wisdom et al., 2010). Disparities such as these arise for a number of reasons. Some disabilities are associated with additional chronic health problems. For example, Down syndrome—a common cause of intellectual disability—is associated with a

number of chronic physical conditions, including heart disease, epilepsy, and leukemia. In the case of Down syndrome, the associated intellectual disability complicates the chronic health conditions; that is, individuals with Down syndrome are less likely to access health services due to fear, lack of understanding on the part of caregivers, and environmental barriers (Vander Ploeg Booth, 2011). For some people with disabilities, the cost of care is a contributing factor to health disparities. For example, Lee, Hasnain-Wynia, and Lau (2012) found that older adults with disabilities encountered greater economic difficulties in seeing a doctor despite having health insurance and a usual source of care.

number of chronic physical conditions, including heart disease, epilepsy, and leukemia. In the case of Down syndrome, the associated intellectual disability complicates the chronic health conditions; that is, individuals with Down syndrome are less likely to access health services due to fear, lack of understanding on the part of caregivers, and environmental barriers (Vander Ploeg Booth, 2011). For some people with disabilities, the cost of care is a contributing factor to health disparities. For example, Lee, Hasnain-Wynia, and Lau (2012) found that older adults with disabilities encountered greater economic difficulties in seeing a doctor despite having health insurance and a usual source of care.

It has been said that people with disabilities represent the U.S.’s largest minority group, a group that comprises individuals of all ages, of all racial and ethnic backgrounds, and from all walks of life (Disability Funders Network, 2012). Health care for this group of people is often complex and costly. More than 25% of healthcare expenditures in the United States are associated with disability care, borne largely by Medicaid and the public sector (Anderson, Armour, Finkelstein, & Wiener, 2010). As educators, nurses can play a significant role in promoting health and wellness, ensuring proper self-care, and improving overall quality of life.

MODELS AND DEFINITIONS

Kaplan and the Center for an Accessible Society (2010) describe four models or perceptions of disabilities that influence the way in which disabilities are addressed in society:

The moral model

The medical model

The rehabilitation model

The disabilities (social) model

The moral model, which views disabilities as sin, is an old model that unfortunately persists in some cultures. When a disability is viewed as sinful, individuals and their families not only experience guilt and shame but may also be denied the care they require. The United Nations has established a set of Standard Rules on the Equalization of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities specifying that individuals with disabilities have a fundamental right of access to care, rehabilitation, and support services (WHO, 2012). WHO assists countries to comply with this United Nations ruling.

The medical and rehabilitation models are similar in that both view disabilities as problems requiring intervention, with the goal being cure or reduction of the perceived deficiency (Kaplan & Center for an Accessible Society, 2010). The health or rehabilitation professional is central to both models. Many positive results have come out of efforts to develop medical and surgical treatment, prostheses and other equipment, and strategies to improve the quality of life of people with disabilities. However, the underlying belief associated with these two models—namely, that people with disabilities must be “fixed”—has been criticized by disability advocates. The medical model, in particular, is blamed for promoting expensive procedures in an attempt to treat conditions that often cannot be cured.

The disabilities model, sometimes referred to as the social model, is the framework that has had the most influence on current thinking. The disabilities model embraces disability as a normal part of life and views social discrimination, rather than the disability itself, as the problem (Kaplan & Center for an Accessible Society, 2010). Whereas the medical and rehabilitation models focus on the problem or condition of the individual, the disabilities or social model views disability as a social construct and focuses on barriers in society that limit opportunities (Matthews, 2009).

The term disability has been defined in a number of ways, with many of these definitions reflecting one or more of the models described by Kaplan and the Center for an Accessible Society (2010).

Most definitions are broad and serve to categorize a wide variety of impairments stemming from injury, genetics, congenital anomalies, or disease. WHO (2012) defines disability as “a complex phenomenon, reflecting an interaction between features of a person’s body and features of the society in which he or she lives.” The connection that this definition makes between an individual’s ability and the expectations of society reflects the spirit of the disabilities model. WHO uses the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) as a framework for measuring health and disability at the individual and population levels. Adopted in 2001, the ICF provides a means of classifying the consequences of disease and trauma and recognizes three dimensions of disabilities: body function/impairment, activity/restrictions, and participation/restrictions (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2012d). The ICF identifies disability as a universal human experience and places emphasis on the impact of a disability rather than on its cause.

Most definitions are broad and serve to categorize a wide variety of impairments stemming from injury, genetics, congenital anomalies, or disease. WHO (2012) defines disability as “a complex phenomenon, reflecting an interaction between features of a person’s body and features of the society in which he or she lives.” The connection that this definition makes between an individual’s ability and the expectations of society reflects the spirit of the disabilities model. WHO uses the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) as a framework for measuring health and disability at the individual and population levels. Adopted in 2001, the ICF provides a means of classifying the consequences of disease and trauma and recognizes three dimensions of disabilities: body function/impairment, activity/restrictions, and participation/restrictions (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2012d). The ICF identifies disability as a universal human experience and places emphasis on the impact of a disability rather than on its cause.

In the United States, the Social Security Administration (SSA) defines disability in terms of an individual’s ability to work. This definition and its associated criteria are designed to be used to determine eligibility for Social Security payments for individuals with severe disabilities. The criteria used by the SSA require that the individual be classified as disabled only if he or she has a condition that interferes with basic work activities. Individuals are approved for disability benefits if they are diagnosed with a condition that is severe enough to prevent them from engaging in gainful employment for an extended period of time. The SSA (2012) does not pay benefits for partial or short-term disability.

On July 26, 1990, President George H. W. Bush signed into law the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). The definition of disability under the ADA is “a physical or mental impairment which substantially limits one or more of the major life activities of the individual” (U.S. Department of Justice, 2009, p. 1). A major life activity includes functions such as caring for oneself, standing, lifting, reaching, seeing, hearing, speaking, breathing, learning, and walking. This significant legislation has extended civil rights protection to millions of Americans with disabilities. The first part of the law, which became effective in January 1992, mandated accessibility to public accommodations. The second part of the law went into effect in July 1992 and required employers to make reasonable accommodations in hiring people with disabilities (Merrow & Corbett, 1994; Pelka, 2012).

Although the ADA’s definition of disability, with its emphasis on physical and mental impairments, may give the impression that it is steeped in the medical or rehabilitation model, the protections it provides are consistent with the disabilities model’s perspective. The ADA legislation makes it illegal to discriminate on the basis of a disability in the areas of employment, public service, public accommodations, transportation, and telecommunications. On a practical level, it means that an individual cannot be denied employment or promotion because of misconceptions or biases in regard to that individual’s disability (Pelka, 2012).

ADA legislation provides the foundation on which all facets of society will be free of discrimination, including the healthcare system. Therefore, health professionals can expect to encounter people with disabilities in every setting in which they practice, such as schools, clinics, hospitals, nursing homes, workplaces, and private homes. Persons with a disability will expect nurses and other healthcare professionals to provide appropriate instruction adapted to their special needs.

THE LANGUAGE OF DISABILITIES

Since the 1960s, the disability rights movement has worked to improve the quality of life of people with disabilities through political action. Through

this effort, tremendous gains have been realized, including improved access to public areas, education, and employment. The disability rights movement also advocates for appropriate use of language in regard to people with disabilities—for example, use of “people-first language” (Haller, Dorries, & Rahn, 2006). As a result of this effort, the federal government uses people-first language in its legislation and many professional journals require authors to use it in their manuscripts.

this effort, tremendous gains have been realized, including improved access to public areas, education, and employment. The disability rights movement also advocates for appropriate use of language in regard to people with disabilities—for example, use of “people-first language” (Haller, Dorries, & Rahn, 2006). As a result of this effort, the federal government uses people-first language in its legislation and many professional journals require authors to use it in their manuscripts.

The term people-first language refers to the practice of putting “the person first before the disability” in writing and speech and “describing what a person has, not what a person is.” People-first language is based on the premise that language is powerful and that referring to an individual in terms of his or her diagnosis devalues the individual (Snow, 2012, p. 3). Consider the following statements:

Justin, a 5-year-old asthmatic, has not responded well to treatment.

Developmentally disabled people, like Marcy, do best when provided with careful direction.

In each of these statements, the emphasis is on the disability, rather than the person. Using people-first language, these statements would be reworded as follows:

Justin is a 5-year-old boy who is diagnosed with asthma. Justin continues to have symptoms despite treatment.

Marcy is a woman with a developmental disability. Marcy wants to learn how to care for herself and learns best when given careful direction.

Using people-first language is more than an exercise. It reflects a deliberate action on the part of the nurse or other healthcare provider to focus on the person with his or her unique qualities rather than to place the individual into an impersonal category based on limitations. The words and labels nurses use to describe people have the ability to influence the way individuals think about themselves and the way individuals are perceived by society. Therefore, it is important that nurses and all health professionals be sensitive to the way in which they write about, talk about, and talk to people with disabilities. Snow (2012) offers the following suggestions for using disability-sensitive language:

Use the phrase congenital disability rather than the term birth defect. The term birth defect implies that a person is defective.

Avoid using the terms handicapped, wheelchair bound, invalid, mentally retarded, special needs, and other labels that have negative connotations.

Speak of the needs of people with disabilities rather than their problems. For example, an individual does not have a hearing problem but rather needs a hearing aid.

Avoid phrases such as suffers from or victim of. Phrases like these evoke unnecessary and unwanted pity.

When comparing people with disabilities to people without disabilities, avoid using phrases such as normal or able-bodied. Phrases such as these place the individual with a disability in a negative light.

THE NURSE EDUCATOR’S ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES

The role of the nurse in teaching persons who have a disability continues to evolve as, more than ever before, clients expect and are expected to assume greater responsibility as self-care agents. Here, the focus is on wellness and strengths—not

limitations—of the individual. The role of the nurse educator in working with clients who have a disability is varied and situation dependent.

limitations—of the individual. The role of the nurse educator in working with clients who have a disability is varied and situation dependent.

The nurse may encounter clients who are newly disabled due to injury or illness or who have an illness that affects an existing disability. The nurse may also work with clients whose health or illness needs are related to their disability only insofar as the disability influences the way in which they learn or respond to treatment. For example, the nurse may teach self-care skills to a client with a new spinal cord injury, teach modification of self-care skills following orthopedic surgery to a client with an old spinal cord injury, or adapt a teaching plan for a client who is blind and newly diagnosed with diabetes. It is the role of the nurse to teach these individuals the necessary skills required to maintain or restore health and maintain independence (habilitation) and to relearn or restore skills lost through illness or injury (rehabilitation). When clients with disabilities are encountered in health and illness settings, nurses are responsible for adapting their teaching strategies to help them learn about health, illness, treatment, and care.

When teaching clients who have a disability, the nurse must assess the degree to which families can and should be involved. Families of individuals who have a new disability are becoming increasingly involved in the individual’s care and rehabilitation efforts. However, when working with a client who has an existing disability, the appropriateness of involving family must be assessed carefully. The nurse must never assume that because a client has a disability, he or she is incapable of self-care.

Because of the complex needs of this population group, healthcare teaching often requires an interdisciplinary team effort. In developing a teaching plan, the nurse must assess the need to involve other health professionals such as physicians, social workers, physical therapists, psychologists, and occupational and speech therapists. As with other clients, the nurse educator has the responsibility to work in concert with clients with disabilities and their family members to assess learning needs, design appropriate educational interventions, and promote an environment that will enhance learning. The teaching plan must reflect an understanding of the client’s disability and incorporate interventions and technologies that will assist the client in overcoming barriers to learning.

Application of the teaching-learning process is intended to promote adaptive behaviors in clients that support their full participation in activities designed to promote health and, in the case of illness, optimal recovery. Emphasis on the various components of the learning process may differ depending on the disability, but it often requires changes in all three domains—cognitive, affective, and psychomotor.

Prior to teaching, assessment is always the first step in determining the needs of clients with respect to the nature of their problems or needs, the short- and long-term consequences or effects of their disability, the effectiveness of the coping mechanisms they employ, and the type and extent of sensorimotor, cognitive, perceptual, and communication deficits they experience. When dealing with persons experiencing a new disability, the nurse must determine the extent of the clients’ knowledge with respect to their disability, the amount and types of new information needed to effect changes in behavior, and the clients’ readiness to learn. Assessment should be based on feedback from the client as well as observation, testing when appropriate, and input from the healthcare team. In some cases, it may be wise to interview family members and significant others to obtain additional information.

When working with a client who has a new disability, it is critical to assess readiness to learn. Diehl (1989) outlines the following questions to

be asked when determining if the timing of the teaching-learning process is appropriate:

be asked when determining if the timing of the teaching-learning process is appropriate:

1. Do the individual and family members demonstrate an interest in learning by requesting information or posing questions in an effort at problem solving or determining their needs?

2. Are there barriers to learning such as low literacy skills, vision impairments, or hearing deficits?

3. If sensory or motor differentiation exists, is the client willing and able to use supportive devices?

4. Which learning style best suits the client in processing information and applying it to self-care activities?

5. Is there congruence between the goals of the client and the goals of the family?

6. Is the environment conducive to learning?

7. Does the client value learning new information and skills as a means to achieve functional improvement?

Prerequisite to the role of the nurse as teacher and provider of care is the nursing responsibility to serve as a mentor to clients and family in coordinating and facilitating the multidisciplinary services required to assist persons with a disability in attaining optimal functioning. This role is especially important when working with a client who has a new disability. When family members or significant others are involved in care and serve as the individual’s support system in the community, they must be invited right from the very beginning to take an active part in learning information as it applies to assisting with self-care activities and treatments for their loved ones (see Appendix B).

TYPES OF DISABILITIES

Disabilities can be classified into two major categories: mental and physical. Physical disabilities typically are those that involve orthopedic, neuromuscular, cardiovascular, or pulmonary problems but may also include sensory conditions such as blindness. A disability is not an illness or disease but rather the consequence of an illness, injury, congenital anomaly, or genetics. Therefore, a physical problem such as a brain injury may result in a physical disability such as impaired ability to ambulate. Physical problems also may result in a mental disability. For example, the mental disability of dementia that is associated with Alzheimer’s disease is a result of physical changes in the brain. Mental disabilities include psychological, behavioral, emotional, or cognitive impairments.

Multiple subcategories of physical and mental disabilities exist. Seven subcategories of physical and mental disabilities have been chosen for discussion in this chapter because they represent common conditions that the nurse is likely to encounter in practice: (1) sensory disabilities, (2) learning disabilities, (3) developmental disabilities, (4) mental illness, (5) physical disabilities, (6) communication disorders, and (7) chronic illness. The specific disabilities that fall under each of these subcategories are described here, along with the teaching strategies that should be used to meet the needs of the learner.

SENSORY DEFICITS

Sensory disabilities include the spectrum of disorders that affect a person’s ability to use one or more of the five senses—auditory, visual, tactile, olfactory, and gustatory. The most common sensory disabilities are those that involve the ability to hear or see. Sensory disabilities can be complex, with multidimensional consequences that the nurse must address when in the role of educator. Nurses must be prepared to attend to the physical and emotional issues that may be related or subsequent to the sensory loss. For example, vision impairment in older adults is associated with depression (Qian, Glaser, Esterberg, & Acharya, 2012). Children with impaired hearing have been

found to have an injury rate twice that of children without hearing impairments (Mann, Zhou, McKee, & McDermott, 2007).

found to have an injury rate twice that of children without hearing impairments (Mann, Zhou, McKee, & McDermott, 2007).

Hearing Impairments

Approximately 35 million Americans have a hearing impairment. Due to the aging of the population, the incidence of hearing loss is growing 1.6 times faster than the growth of the U.S. population, with this disability predicted to affect a total of 53 million people by 2050 (Kochkin, 2009). Hearing impairment is a disability that is experienced by people of all ages. In the United States, 2 to 3 of every 1000 children are born deaf or hard of hearing; 50% to 60% of these children are born with a hearing loss that is genetic in nature (Morton, 2009). Nine out of every 10 children who are born deaf are born to parents who can hear (National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders [NIDCD], National Institutes of Health, 2012).

The incidence of hearing loss increases with age. Approximately 18% of all American adults aged 45-64 years have a hearing impairment. This share increases to 47% by age 75, with men being more likely to develop a hearing impairment than women (NIDCD, 2012). Although adult-onset hearing loss is often associated with exposure to loud sounds or noises, approximately 4000 new cases of sudden deafness occur in the United States every year (CDC, 2012b).

People with impaired hearing—both the deaf and the hard of hearing—have a complete loss or a reduction in their sensitivity to sounds. Hearing loss is generally described according to three attributes: type of hearing loss, degree of hearing loss, and configuration of the hearing loss (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association [ASHA], 2012b). The three basic types of hearing loss are the following:

1. Conductive hearing loss: A type of hearing loss that is usually correctable and causes reduction in the ability to hear faint noises. Conductive hearing loss occurs when the ear loses its ability to conduct sound—for example, when the ear is plugged as a result of ear wax, a foreign body, a tumor, or fluid.

2. Sensorineural hearing loss: A type of hearing loss that is permanent and caused by damage to the cochlea or nerve pathways that transmit sound. Sensorineural hearing loss is sometimes referred to as nerve deafness. It not only results in a reduction in sound level but also leads to difficulty in hearing certain sounds. Although they do not “cure” the hearing impairment, cochlear implants and hearing aids can improve hearing in persons with this type of disability.

3. Mixed hearing loss: A type of hearing loss that is a combination of conductive and sensorineural losses.

People with hearing loss may have a problem with one or both ears. The degree of hearing loss experienced by people with a hearing impairment is classified on a scale ranging from slight to profound. Although health professionals may use the scale to differentiate people who are classified as being deaf or hard of hearing, clients themselves do not always agree with this classification. According to the National Association of the Deaf, how people label themselves is very personal and depends on a number of variables, including how closely the individual identifies with the Deaf community. Therefore, some individuals with profound hearing loss may prefer to refer to themselves as hard of hearing rather than deaf (National Association of the Deaf, 2010).

When working with, writing about, or preparing printed information for individuals with hearing impairments, it is important that health professionals be sensitive to the use of language. For example, the use of people-first language is somewhat controversial in the Deaf community. There is a recognized Deaf culture with a shared identity, language, and other cultural components

(Johnson & McIntosh, 2009; McLaughlin, Brown, & Young, 2004). Because of this shared culture of which they are proud, many Deaf people want to be recognized as deaf because it is a reflection of who they are as people. As with other cultural groups, health professionals as educators should take the steps necessary to get to know their clients and their preferences related to the use of this type of language. In regard to the word deaf, it is suggested that the word deaf with a lowercase d be used when referring to the physical condition of not being able to hear, and the word Deaf with an uppercase D be used when referring to people affiliated with the Deaf community or Deaf culture (Strong, 1996).

(Johnson & McIntosh, 2009; McLaughlin, Brown, & Young, 2004). Because of this shared culture of which they are proud, many Deaf people want to be recognized as deaf because it is a reflection of who they are as people. As with other cultural groups, health professionals as educators should take the steps necessary to get to know their clients and their preferences related to the use of this type of language. In regard to the word deaf, it is suggested that the word deaf with a lowercase d be used when referring to the physical condition of not being able to hear, and the word Deaf with an uppercase D be used when referring to people affiliated with the Deaf community or Deaf culture (Strong, 1996).

Communication is a primary concern for health professionals working with people who are deaf or hard of hearing. Regardless of the degree of hearing loss, any person with a hearing impairment faces communication barriers that interfere with efforts at patient teaching (Stock, 2002). Hearing loss poses a very real communication problem because some individuals who are deaf or hearing impaired also may be unable to speak or have limited verbal abilities and vocabularies (Lederberg, Schick, & Spenser, 2012). This is especially true for adults who are prelingually deaf—that is, they have been deaf since birth or early childhood. They and speakers of other languages share many of the same problems in learning English. Problems with clients understanding health- and illness-related vocabulary also may be exacerbated with clients who are deaf. In a study of knowledge of health-related vocabulary among adults who were deaf, Pollard and Barnett (2009) found that the Deaf population is at risk for low health literacy.

In many families with children who are deaf, American Sign Language (ASL) is used in the home and is the first language children learn. For other children who are raised in an environment where Deaf culture predominates, ASL is the medium of social communication among peers, which reinforces English as a second language. Although some children who primarily use ASL have difficulty achieving fluency in English, some evidence suggests that a high level of ASL proficiency is related to strong English literacy skills (Alliance for Students with Disabilities in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics [AccessSTEM], 2010; Vicars, 2003).

It is clear that individuals who are deaf will have different skills and needs depending on the type of deafness and the amount of time they have been without a sense of hearing. Those who have been deaf since birth will not have had the benefit of language acquisition. As a result, they may not possess understandable speech and may have limited reading and vocabulary skills. Most likely, their primary modes of communication will be sign language and lipreading.

In recent years, research has inspired new hope for children with severe hearing loss to develop language skills. In 1984, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved marketing of the first cochlear implant, a device that restores partial hearing by sending signals directly to the auditory nerve fibers by bypassing damaged hair cells in the inner ear (American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, 2010). Research has shown that cochlear implants have a positive effect on language development when inserted in very young children (Ertmer, Young, & Nathani, 2007; Nicholas & Geers, 2007). However, Blume (2010) raises important ethical issues about informed consent, deafness as a social culture, and the medical model paradigm of deafness being seen as pathology when decisions are made by parents and physicians to implant an “artificial ear” in young children who are born without a sense of hearing.

If deafness has occurred after language has been acquired, Deaf people may speak quite understandably and have facility with reading and writing and some lipreading abilities. If deafness has occurred in later life, often caused by the

process of aging, affected individuals will probably have poor lipreading ability, but their reading and writing skills should be within average range, depending on their educational and experiential background. If aging is the cause of hearing loss, visual impairments also may be a compounding factor. Because vision and hearing impairments are two common sensory losses in the older adult, these deficits pose major communication problems when teaching older clients.

process of aging, affected individuals will probably have poor lipreading ability, but their reading and writing skills should be within average range, depending on their educational and experiential background. If aging is the cause of hearing loss, visual impairments also may be a compounding factor. Because vision and hearing impairments are two common sensory losses in the older adult, these deficits pose major communication problems when teaching older clients.

People with hearing impairments, like other individuals, require health care and health education information at various periods during their lives. People within the Deaf community are diverse, and nurses will encounter many differences among their Deaf clients. Therefore, assessment is a critical first step in client education. It is important to determine the extent of the client’s hearing loss and the use of hearing aids, cochlear implants, or other types of assistive equipment. Individuals with hearing loss often experience social isolation and feelings of inadequacy (Fusick, 2008), and these feelings may contribute to a lack of confidence when faced with health challenges. Nurses should assess the client’s prior knowledge of the issue being addressed, recognizing that people who have hearing impairments may not have been exposed to the same kinds of health information as people who can hear (Pollard, Dean, O’Hearn, & Haynes, 2009). Finally, it is important to remember that Deaf individuals will always rely on their other senses for information input, especially their sense of sight. For patient education to be effective, then, communication must be visible.

Because there are several different ways to communicate with a person who is deaf, one of the first things nurses need to do is ask clients to identify their communication preferences. Sign language, written information, lipreading, and visual aids are some of the common choices. Although one of the simplest ways to transfer information is through visible communication signals such as hand gestures and facial expressions, this method will not be adequate for any lengthy teaching sessions.

The following modes of communication are suggested as ways to decrease the barriers of communication and facilitate teaching and learning for clients with hearing impairments in any setting.

SIGN LANGUAGE

Many people who are deaf consider ASL to be their primary language and preferred mode of communication. For children who are raised in an environment where Deaf culture predominates, ASL is the medium of social communication among peers, which reinforces the role of English as a second language. Most, if not all, of these children have difficulty achieving native-like fluency in English. ASL differs from simple finger spelling, which is a method of using different hand positions to represent letters of the alphabet. In contrast, ASL is a complex language made up of signs as well as finger spelling combined with facial expressions and body position. Eye gaze and head and body shift are also incorporated into the language (Oregon’s Deaf and Hard of Hearing Services, 2010).

The nurse who does not know ASL is advised to obtain the services of a professional interpreter. Sometimes a family member or friend of the patient skilled in signing is willing and available to act as a translator during teaching sessions. However, just as it is preferable to use a professional interpreter when dealing with a client with a different spoken language, so it is also preferable to use a professional interpreter for a client who uses sign language (Scheier, 2009). Family members and friends may have difficulty translating medical words and phrases and may be hesitant to convey information that may be upsetting to the client. Prior to enlisting the assistance of an interpreter, whether family member or professional, the nurse should always be certain to obtain the patient’s permission to do so. Information

communicated regarding health issues may be considered personal and private. If the information to be taught is sensitive or confidential, it is advised that family or friends should not be enlisted as interpreters. Hiring a certified language interpreter is often the best strategy.

communicated regarding health issues may be considered personal and private. If the information to be taught is sensitive or confidential, it is advised that family or friends should not be enlisted as interpreters. Hiring a certified language interpreter is often the best strategy.

When a nurse is considering the services of an interpreter, he or she should consult the client. Federal law (Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, PL 93-112) requires that health facilities receiving federal funds secure the services of a professional interpreter upon request of a client. If the patient cannot provide the names of interpreters, the nurse can contact the state Registry of Interpreters of the Deaf (RID). This registry can provide an up-todate list of qualified sign language interpreters.

When working with an interpreter, the nurse should stand or sit next to the interpreter. He or she should talk at a normal pace and look and talk directly to the deaf person when speaking. The interpreter will convey information to the client as well as share responses from the client. It is important to remember that ASL does not provide a word-forword translation of the spoken or written word and that misunderstandings can occur. Because client education involves the exchange of important, often very detailed information, the nurse must ascertain that the client understands the information given by asking questions, asking for demonstrations, allowing the client to ask questions, and using other appropriate assessment strategies (Scheier, 2009).

LIPREADING

Lipreading is the process of interpreting speech by observing movements of the face, mouth, and tongue (Feld & Sommers, 2009). One common misconception among hearing persons is that all people who are deaf can read lips. This is a potentially dangerous assumption for the nurse to make. Not all people who are deaf read lips, and even among those who do, lipreading may not be appropriate for health education or other forms of client-professional communication. Among deaf persons in general, word comprehension while lipreading is only about 35%. Therefore, only a skilled lip-reader will obtain any real benefit from this form of communication (Rouger et al., 2007).

When working with a client who is lipreading, it is not necessary to exaggerate lip movements, because this action will distort the movements of the lips and interfere with interpretation of the words. If lipreading is preferred by the client, speakers must be sure to provide sufficient lighting on their faces and remove all barriers from around the face, such as gum, pencils, hands, and surgical masks. Beards, mustaches, and protruding teeth also present a challenge to the lip-reader. Because less than half of the English language is visible on the lips, one should supplement this form of communication with signing or written materials.

WRITTEN MATERIALS

Written information is probably the most reliable way to communicate, especially when understanding is critical. In fact, nurse educators should always write down the important information as a supplement to the spoken word even when the deaf person is versed in lipreading. Written communication is the safest approach, even though it is time consuming and sometimes stressful.

Printed client education materials must always match the readability level of the audience. When preparing written materials for clients who are deaf, it is prudent to keep the message simple. Approximately 35% of 12th-grade students are proficient in reading (Schneider, 2007). In comparison, the reading level of the average high school graduate who is deaf has historically been reported to be at about the fourth-grade level. Although recent studies suggest that students who are deaf are making strides in their reading performance, the data on this point are inconclusive and many deaf people still struggle with the written word (Easterbrook & Beal-Alvarez, 2012).

When preparing written instructional information, it is important to keep in mind that a person

with limited reading ability often interprets words literally. Therefore, instructions should be clear, with minimum use of words or phrases that could be misinterpreted or confusing. For example, instead of writing, “When running a fever, take two aspirin,” write “For a fever of 100.5°F or higher, take two aspirin.” The second message is clearer in that it avoids confusion over the interpretation of the word “running” and provides clarification of the word “fever.” Visual aids such as simple pictures, drawings, diagrams, models, and the like are also very useful media as a supplement to increase understanding of written materials.

with limited reading ability often interprets words literally. Therefore, instructions should be clear, with minimum use of words or phrases that could be misinterpreted or confusing. For example, instead of writing, “When running a fever, take two aspirin,” write “For a fever of 100.5°F or higher, take two aspirin.” The second message is clearer in that it avoids confusion over the interpretation of the word “running” and provides clarification of the word “fever.” Visual aids such as simple pictures, drawings, diagrams, models, and the like are also very useful media as a supplement to increase understanding of written materials.

VERBALIZATION BY THE CLIENT

Sometimes clients who are deaf will choose to communicate through speaking, especially if they have established a rapport and a trusting relationship with the nurse. The tone and inflection of the voice of a client who is deaf may be different than normal speech, so nurses must make time for listening carefully. Because the information that is shared during a teaching session is so important, an optimal environment for communication must be created. A quiet, private place should be selected so that the client’s words can be heard. Nurses should listen without interruptions until they become accustomed to the person’s particular voice intonations and speech rhythms. Those who still have trouble understanding what a client is saying might try writing down what they hear, which may help them to get the gist of the message.

SOUND AUGMENTATION

For those patients who have a hearing loss but are not completely deaf, hearing aids are often a useful device. A client who has already been fitted for a hearing aid should be encouraged to use it, and it should be readily accessible, fitted properly, turned on, and with the batteries in working order. If the client does not have a hearing aid, with permission of the patient and family, the nurse should make a referral to an auditory specialist, who can determine whether such a device is appropriate for the patient. Only one out of five people who could benefit from a hearing aid actually wear one (NIDCD, 2012). Cost contributes to this problem. Although Medicare policies vary from state to state, as a rule, Medicare does not pay for routine hearing examinations or hearing aids. Under some circumstances, Medicare will pay for diagnostic hearing tests when hearing loss is suspected as a result of illness or treatment (Medicare, 2012). Therefore, it is important to seek permission of the client before initiating the referral for a hearing examination or hearing aid.

Another means by which sounds can be augmented is by cupping one’s hands around the client’s ear or using a stethoscope in reverse. That is, the patient puts the stethoscope in his or her ears, and the nurse talks into the bell of the instrument (Babcock& Miller, 1994).

If the patient can hear better out of one ear than the other, speakers should always stand or sit nearer to the good ear, use slow speech, provide adequate time for the patient to process the message and to respond, and avoid shouting, which distorts sounds. It is not necessarily an increase in decibels that makes a difference, but rather the tone, rhythm, articulation, and pace of the words.

TELECOMMUNICATIONS

Telecommunication devices for the deaf (TDD) are an important resource for patient education. Television decoders for closed-caption programs are an important tool for further enhancing communication. Caption films for patient education are also available free of charge through Modern Talking Pictures and Services. Under federal law, these devices are considered to be reasonable accommodations for deaf and hearing-impaired persons. However, nurses should note that translation of the spoken word on health-related videos created for the hearing population, without the tone of voice, voice level, and other strategies speakers use to emphasize a point, may alter the message

that is conveyed to deaf clients (Pollard et al., 2009; Wallhagen, Pettengill, & Whiteside, 2006).

that is conveyed to deaf clients (Pollard et al., 2009; Wallhagen, Pettengill, & Whiteside, 2006).

In summary, nurses can apply the following guidelines when using any of the aforementioned modes of communication (McConnell, 2002; Navarro & Lacour, 1980).

Nurse educators should:

Be natural, not rigid or stiff, or do not attempt to over-articulate speech.

Use short, simple sentences.

Speak at a moderate pace, pausing occasionally to allow for questions

Be sure to get the deaf person’s attention by a light touch on the arm before beginning to talk.

Face the patient and stand no more than 6 feet away when trying to communicate.

Ask the client’s permission to eliminate environmental noise by lowering the television, closing the door, and so forth.

Make sure the client’s hearing aid is turned on and the client’s glasses are clean and in place.

Nurse educators must refrain from the following:

Talking and walking at the same time.

Bobbing their head excessively.

Talking from another room or turning away from the person with hearing loss while communicating.

Standing directly in front of a bright light, which may cast a shadow across their face or glare directly into the client’s eyes.

Joking, using slang, or using other language the client might misunderstand.

Placing an intravenous line in the hand the patient will need for sign language.

No matter which methods of communication for teaching are chosen, it is important to confirm that health messages have been received and understood. It is essential to validate client comprehension in a nonthreatening manner. In attempts to avoid embarrassing or offending one another, patients as well as healthcare providers will often acknowledge with a smile or a nod in response to what either party is trying to communicate when, in fact, the message is not understood at all. To ensure that the health education requirements of deaf and hearing-impaired clients are being met, the nurse educator must find effective strategies to communicate the intended message clearly and precisely while at the same time demonstrating acceptance of individuals by making accommodations to suit their needs (Harrison, 1990). Clients who have lived with a hearing impairment for a while usually can indicate which modes of communication work best for them.

Visual Impairments

The American Foundation for the Blind (AFB) estimates that more than 20 million people in the United States are blind or visually impaired. Although almost 5 million of these people are older than the age of 65, visual impairment is not a problem that is restricted to adults. More than half a million children in the United States have issues with vision. Approximately 1.3 million Americans have vision problems severe enough to classify them as legally blind, and about 60,000 of these individuals are children (American Federation for the Blind, 2012; AFB, 2012). Approximately 100 million Americans require corrective lenses (Vitale, Cotch, & Sperduto, 2006).

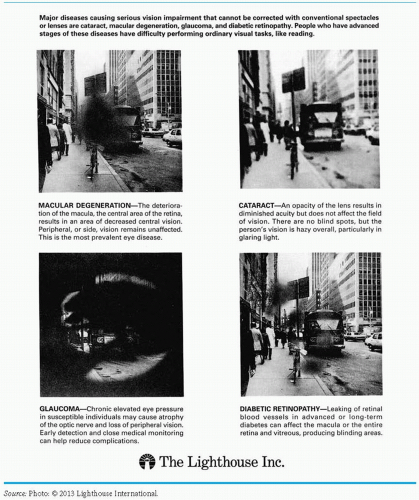

There are many causes of blindness and visual impairment (Figure 9-1). Disease is the major cause of loss of vision in adults, with cataracts, age-related macular degeneration, glaucoma, and diabetic retinopathy accounting for the greatest

number of disease-related impairments (Braille Institute, 2012; National Institutes of Health, 2012). Although vitamin A deficiency is the leading cause of blindness in children worldwide, amblyopia and strabismus, optic nerve neuropathy, prematurity, low birth weight, and congenital conditions such as congenital cataracts are the most common factors leading to blindness in children in the United States (Lighthouse International, 2012).

number of disease-related impairments (Braille Institute, 2012; National Institutes of Health, 2012). Although vitamin A deficiency is the leading cause of blindness in children worldwide, amblyopia and strabismus, optic nerve neuropathy, prematurity, low birth weight, and congenital conditions such as congenital cataracts are the most common factors leading to blindness in children in the United States (Lighthouse International, 2012).

Although severe vision loss provides the greatest challenge to the nurse as educator, it is important to note that mild to moderate vision loss is commonplace. The most prevalent condition that results in some degree of visual impairment is myopia (nearsightedness). This refractive error usually can be corrected with eyeglasses or contact lenses. As the population ages and becomes more racially and ethnically diverse, the rates of myopia have increased in the United States and in the population worldwide. Improving the vision of those individuals with myopia through refractive correction is considered to be an important public health initiative. Correction of this common visual impairment has implications for safety and quality of life by reducing falls, fractures, depression, and car accidents.

A visual impairment is defined as some form and degree of visual difficulty and includes a wide spectrum of deficits, ranging from partial vision loss to total blindness; it may also include visual field limitations, such as tunnel vision, alternating areas of total blindness and vision, and color blindness. In the United States, a person is determined to be legally blind if vision is 20/200 or less in the better eye with correction or if visual field limits in both eyes are within 20 degrees in diameter. Approximately 90% of people who are legally blind have some degree of vision. Typically, a person who is legally blind is unable to read the largest letter on the eye chart with corrective lenses (Braille Institute, 2012). In comparison, total blindness is defined as an inability to perceive any light or movement (Braille Institute, 2012).

Clients who seem to be legally blind but who have not been evaluated by a low-vision specialist should be provided with contact information for these sources: the local Blind Association and the local Commission for the Blind and Visually Handicapped. Clients may require assistance in negotiating the complex system and in obtaining services.

Fortunately, many devices are available to help legally blind persons maximize their remaining vision. Clients who are without sight most likely have had services and are familiar with those adaptations that work best for them. However, depending on patients’ situations and the circumstances under which the nurse is teaching, the nurse educator may want to further investigate their background to ensure that the most appropriate format and tools for communicating with visually impaired clients are being used.

Healthcare encounters present challenges for both the client with low vision or blindness and for the professionals who care for them. In a series of focus groups with people with blindness or low vision, O’Day, Killeen, and Iezonni (2004) identified four barriers encountered in healthcare settings:

Lack of respect

Communication problems

Physical barriers

Information barriers

Lack of respect was the basis for many of the negative healthcare encounters described by the participants. For example, participants felt that healthcare providers often made assumptions that clients would be unable to participate in their own care and recovery. Subsequent studies supported this finding. In a study of barriers to low-vision rehabilitation, Southhall and Wittich (2012) found that clients with visual impairments were

often reluctant to disclose their vision loss for fear of triggering prejudice and discrimination.

often reluctant to disclose their vision loss for fear of triggering prejudice and discrimination.

Directing comments to a sighted companion rather than to the client was another common complaint. In terms of education, participants expressed concern that many health providers are not prepared to care for clients with visual impairments. Without Braille versions of information sheets, audiotaped instructions, and other assistive strategies, clients with visual impairments left teaching sessions feeling anxious and, most important, without the information required.

The following are some tips nurses might find helpful when teaching a client with a visual impairment:

Assessment is always an important first step, and it is crucial not to make assumptions. The needs of a person who is blind may be very different from one who has low vision. Additionally, multiple disabilities must be considered, particularly when working with older adults (Manduchi & Coughlan, 2012).

A low-vision specialist can prescribe optical devices such as a magnifying lens (with or without a light), a telescope, a closed-circuit TV, or a pair of sun shields, any of which will enable nurses to adapt their teaching material to meet the needs of their clients.

Persons who have long-standing blindness have learned to develop a heightened acuity of their other senses of hearing, taste, touch, and smell. When conveying messages, they rely on their auditory and tactile senses as a means to help them assimilate information from their environment. Usually their listening skills are particularly acute; it is not necessary to shout. When teaching, the nurse should speak in a normal tone of voice.

Unlike sighted persons, people who are blind cannot attend to nonverbal cues such as hand gestures, facial expressions, and other body language. Those who approach a person who is visually impaired should always announce their presence, identify themselves, and explain clearly why they are there and what they are doing. Because the memory and recall of a person who is blind are better than the abilities of most sighted persons, educators can use this talent to maximize learning (Babcock & Miller, 1994).

When explaining procedures, educators should be as descriptive as possible. They should expound on what they are doing and explain any noises associated with treatments or the use of equipment. The client should be allowed to touch, handle, and manipulate equipment. Instructors should use the client’s sense of touch in the process of teaching psychomotor skills as well as when the client is learning to return-demonstrate.

Because people who are blind are unable to see shapes, sizes, and the placement of objects, tactile learning is an important technique to use when teaching. For example, such patients can identify their medications by feeling the shape, size, and texture of tablets and capsules. Gluing pills to the tops of bottle caps and putting medications in different-sized or -shaped containers will aid them in identifying various medications (Boyd, Gleit, Graham, & Whitman, 1998). In this way, they will be able to be more self-sufficient in following their prescribed regimens. Also, keeping items in the same place at all times will help them independently locate their belongings. Arranging things in front of clients in a regular clockwise fashion

will facilitate learning to perform a task that must be accomplished in an orderly, step-by-step manner (McConnell, 1996).

When using printed or handwritten materials, enlarging the print (font size) is typically an important first step for those individuals who have diminished sight.

Color is a key factor in whether a person who is visually impaired can distinguish objects. Assessment should be done on the medium in which the client sees better—black ink on white paper or white ink on black paper. Colors and varying hues of color other than black and white are more difficult to discriminate by the older person with vision problems.

Proper lighting is of utmost importance in assisting clients who are visually impaired to read the printed word. Regardless of the print size and the color of the type and paper used, if the light is insufficient, clients with visual impairments will have a great deal of difficulty reading print or working with objects.

Providing contrast is a very helpful technique. For example, using a dark placemat with white dishes or serving black coffee in a white cup will allow persons with visual problems to better see items in front of them. Likewise, clients with visual impairment should be taught to place pills, equipment, or other materials they are using on a contrasting background to help them to visualize the material they are working with.

Large-print watches and clocks with either black or white backgrounds are available through a local chapter for the visually handicapped.

Audiotapes and cassette recorders are very useful tools. Today, many health education texts as well as other printed health information materials are available as talking books and can be obtained through the National Library Service or through the state library for the blind and visually handicapped. These services are also available for people with other disabilities.

Oral instructions can be audiotaped so that information can be listened to as necessary at another time and place. Repetition allows the opportunity for memorization to reinforce learning.

The computer is a popular and useful tool for this population of learners. At the most basic level, clients can be taught to make use of standard features such as screen magnifiers, high contrast, and screen-resolution adjustments to make information on their computer screen easier to see. Many computer packages and electronic devices for reading also come equipped with a textto-speech converter. More advanced assistive technology for the computer includes synthetic speech; screen readers; and Braille keyboards, displays, and printers as well as other types of software and hardware for use by people with visual impairments. For example, screen enlargement software can make the text on a computer screen 2 to 16 times larger than the normal view and invert colors for those individuals who have difficulty with the typical blackon-white display. This feature makes it possible for the nurse to scan a standard document and display it in a large form on the computer screen (University of Washington, 2012).

Most blind associations have a Braille library, or clients can access appropriate resources for information, such as the National Braille Press. Local blind associations might print patient education materials in Braille so they can be used by learners with visual impairments.

When assisting the person who is blind to ambulate, the nurse should always use the sighted guide technique; that is, the guide should allow the person to grasp his or her forearm while the guide walks about one half-step ahead of the blind person. Another resource person who can help with ambulation is an orientation and mobility instructor. These specialists are available in most school districts and the local associations for the blind.

Whenever possible, teaching sessions should be held in a quiet, private space where the client can focus on what is being taught without distraction. Allow adequate time so that the instruction can be delivered in an unhurried manner.

Diabetes education consumes a great deal of a nurse educator’s teaching time and presents unique challenges. Because of the high incidence of this disease in the American population, diabetic retinopathy is a major cause of blindness. Persons who have lost their sight due to diabetic retinopathy probably have already mastered some of the necessary skills to care for themselves but will need continued assistance. Of course, it is also possible for persons with visual impairments to be diagnosed at a later time with diabetes. In either case, at some point in the course of their lives, these persons will need to learn how to use appropriate adaptive equipment.

Fortunately, there also has been continuous improvement in the equipment used for self-monitoring of blood glucose levels and for self-injection of insulin. Easy-to-use monitors with large display screens or voice instructions are available now. Just as several devices for monitoring blood glucose levels have been developed, new nonvisual adaptive devices for measuring insulin have become available as well. For example, insulin pens that contain prefilled dosages and make use of built-in magnifiers have made insulin administration much easier for clients who have difficulty reading a syringe (Cohen & Ayello, 2005).

LEARNING DISABILITIES

Over the past 30 years, learning disabilities have emerged as a major issue in the United States (CDC, 2008). Although often associated with school-aged children, these neurologically based disorders begin in childhood and persist through adulthood (National Institute for Literacy, 2008). Learning disorders are complex conditions that are frequently hidden and vary from individual to individual. As a result, they are often misunderstood and underestimated (Bridges to Practice, 2004).

A definitive definition of the term learning disability (LD) has been the subject of a great deal of controversy over the years as educators and psychologists alike have debated the issues (Crandell, Crandell, & VanderZaden, 2012; Santrock, 2011; Snowman, McCown, & Biehler, 2012; Ysseldyke & Algozzine, 1983). Because of the multidisciplinary nature of the field, experts continue to engage in the discussion and agree that the underlying mechanisms are complex and that many unanswered questions remain. However, despite the debate, professionals agree on some common characteristics of learning disabilities (Child Development Institute, 2012; LDOnline, 2012; National Joint Committee on Learning Disabilities, 2011):

Learning disabilities involve learning problems and uneven patterns of development in children and adults.

Learning disabilities that are identified in childhood may persist into adulthood. For example, difficulty with language development in a preschool child may signal long-term learning challenges in the school-aged child that may go unresolved through the adult years.

Learning disabilities are neurobiologically based and are caused by factors other than environmental disadvantage, mental retardation, and emotional disturbance.

Learning disabilities are the result of a different wiring of the human brain that influences the way in which information is received, processed, and communicated.

A number of definitions of learning disabilities can be found in the literature. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (1997) defines learning disability as a “disorder in one or more of the basic psychological processes involved in understanding or in using language, spoken or written, that may manifest itself in an imperfect ability to listen, think, speak, read, write, spell or do mathematical calculations” (Learning Disabilities Roundtable, 2005). This definition stands as the accepted working definition for purposes of assessment, diagnosis, and categorization of an array of learning disabilities.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree