CHAPTER 3 Ecological sustainability and human health

Concerns about the environment now include ecosystem viability and the impact this will have on human survival. Innovative responses will be required by the health sector to the projected social, psychological and physical health consequences of natural resource depletion and pollution of air, water and soil, climate change, and food shortages and changing disease patterns. Society will expect health workers to take a leading role. ‘Top down’ and ‘bottom up’ approaches will be needed. Currently the health sector is unprepared for this emerging role. This will be one of the most challenging public health issues for this century.

Chapter 3 builds on the ideas presented about the determinants of health and illness discussed in Chapter 1 and the core concepts and values discussed in Chapter 2. This chapter will present an introduction to ecological sustainability for health workers by providing: definitions and principles of ecological sustainability; a rationale for the engagement of the health sector; and case studies for health professionals working with individuals, in community settings, and as citizens playing a leading role in ensuring ecosystem viability and, consequently, good human health. Links between the physical, emotional and social health of people, the health of the environment and the implications for practice will be made.

WHAT IS ECOLOGICAL SUSTAINABILITY?

The health of humans is dependent upon a healthy ecosystem. The Convention of Biological Diversity defined an ecosystem as a ‘dynamic complex of plant, animal and micro-organism communities and their non-living environment interacting as a functional unit’ (United Nations Conference on Environment and Development [UNCED] 1992a). A healthy ecosystem is a principal determinant of human health. On the health iceberg, presented in Chapter 1, we would place ecosystem health well below the waterline, acknowledging that the interplay between the social and environmental determinants on health and illness are inextricably linked. In Labonté’s (1997) framework of the determinants of health, also presented in Chapter 1, ecosystem viability, sustainable development and convivial communities are outlined as health-promoting conditions, while natural resource depletion, the enhanced greenhouse effect and polluted environments are located in the risk conditions along with poverty, low social status and discrimination. These are the fundamental determinants of illness.

We can promote ecological sustainability and consequently human health by ‘using, conserving and enhancing the community’s resources so that ecological processes, on which life depends, are maintained, and the total quality of life, now and in the future, can be increased’ (Australian Government 1992). Working towards ecological sustainability is consistent with Primary Health Care principles. Ecological sustainability will be achieved with consequent improvement in the quality of life of humans through social justice, intergenerational equity, employing the precautionary principle and biodiversity conservation. These principles enable us to prevent and reverse adverse impacts of human activities on the ecosystem, while continuing to allow the sustainable, equitable development of societies (see Box 3.1). The philosophy and action presented throughout this book through the Primary Health Care lens is entirely consistent with working towards ecological sustainability and health. The appendices of this book all affirm that health is a human right, is determined by the environment, both social and natural, and each provides guidance for environmental stewardship, governance, and citizen participation.

BOX 3.1 Principles of ecological sustainability

These overarching principles reflect the predominant spirit and intent of sustainable development as advocated by the Rio de Janeiro Declaration on Environment and Development (UNCED 1992b).

Precautionary principle ‘Where there are threats of serious or irreversible environmental damage, lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing measures to prevent environmental degradation. In the application of the precautionary principle, public and private decisions should be guided by careful evaluation to avoid, wherever practicable, serious or irreversible damage to the environment and an assessment of the risk-weighted consequences of various options’ (Deville & Harding 1997: 13).

Intergenerational equity Extends the principle of fairness and justice to future generations. The principle holds that the present generation has a stewardship role in conserving the natural and cultural resources of the earth and all species so that future generations may enjoy the same quality of life as the present generation.

Biodiversity conservation ‘… the protection of ecosystems, natural habitats and the maintenance of viable populations of species in natural surroundings’ (UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs 1992). Biodiversity refers to the variety of all life on earth — plants, animals and microorganisms, as well as the genetic material they contain and the ecological systems in which they occur. Biodiversity is necessary to maintain our atmosphere, climate, water and soils in a healthy state.

There are aesthetic, cultural and ethical reasons for maintaining biodiversity. Humans define themselves through their ecosystems. It is an essential element of intergenerational equity and also, other species have as much right to the earth as humans.

Environmental resource accounting A means of benchmarking the current usage against ideal usage and then, for the future, reporting on the progress.

Community participation Acknowledges that the practice of sustainable development is dependent upon the involvement of communities at the local level.

WHY IS ACKNOWLEDGING ECOLOGICAL SUSTAINABILITY IMPORTANT TO THE HEALTH SECTOR?

Changes in the ecosystem at the global level now pose different challenges. It is tempting to think of climate change as the only environmental health issue. In fact climate change is a symptom of widespread degradation and pollution of land, water and air. Changes to natural ecosystems world-wide have been more rapid over the past 50 years than any other comparable time in history (WHO 2005b). These changes are primarily attributed to human activity. We are now operating in an ecological deficit. The Ecological Footprint (Rees & Wackernagal 1995) illustrates that, as a global community, we need about 1.2 planets to meet our average resource consumption levels (Environment Protection Authority 2008). Combinations of a burgeoning population and over-consumption have contributed to enhanced greenhouse effect, resource wars and pollution. Water, soil and air, those things fundamental to our survival, have been degraded. Collier (2003) analysed 54 large-scale civil wars that occurred between 1965 and 1999 and found that a higher ratio of primary commodity exports to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) ‘significantly and substantially’ increases the risk of conflict, meaning that civil war becomes more likely when countries export commodities as a priority over local public health and nutrition needs. This is unsustainable. We need to make a long-term commitment to integrated action and the health workforce has a key role in human health protection and in supporting systems and programs based on sustainability principles.

WHAT ARE THE PREDICTED CHANGES AND LIKELY HEALTH IMPACTS

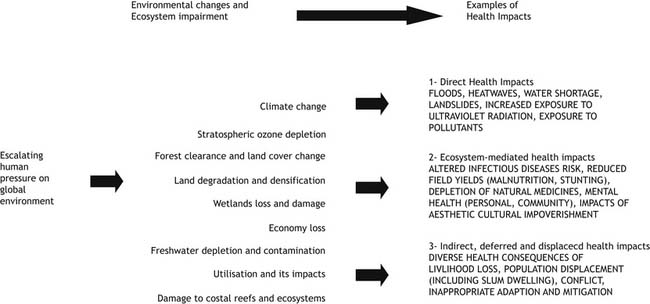

Ecosystem and Human Well-being Health Synthesis (WHO 2005b) was produced as a result of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA) referred to in Chapter 1 (see Box 1.2). The report is a synthesis of the evidence produced by the MEA about how ecosystem changes do or could affect human health and wellbeing (WHO 2005b). Figure 3.1 encapsulates those impacts. The figure describes the casual pathway from escalating human pressures on the environment through to ecosystem changes resulting in diverse health consequences. Not all ecosystem changes are included. Some changes can have positive effects (e.g. food production). The effects may be immediate and long-term, direct and indirect, local and global.

FIGURE 3.1 Why do ecosystems matter to human health?

(Source: Corvalan, Hales, McMichael 2005: 1) Reproduced with the permission of the World Health Organization.

Indirect and deferred health impacts of degraded ecosystems

Climate variability has raised the level of public debate in recent times about the interdependence of the health of humans and the health of the planet at a global level. Global warming is a symptom of a degraded ecosystem. Until now the effects from global warming have been largely indirect. There is uncertainty about the details, magnitude, timing and health consequences for the future (McMichael & Campbell-Lendrum et al 2003). However, the heatwaves in August 2003 in Europe contributed to over 35000 premature deaths (BMJ 2005). The annual global death rate from global warming is already estimated at 60000 (Horton & McMichael 2008). It is predicted that global warming will alter ecosystems, agricultural productivity, food supply and cause resource wars. The rising salinity of water tables will damage more farmland. Inappropriate adaptation and mitigation strategies to global warming will give rise to population displacement and further livelihood loss. Heat increases due to global warming will stress and endanger the elderly, the frail and those working in high heat jobs. Heat related deaths result from increased strain on the cardiovascular system, industrial accidents, behavioural disruption and heat stroke. Rising seas will also cause added exposure to toxic and infectious agents due to disruption of waste disposal. Global warming is also expected to change human exposure to infectious disease agents — both vector-borne and microbes. The impact of climate change on diseases such as malaria, dengue fever, Murray Valley encephalitis, Ross River and Barmah Forest Virus is already becoming evident (Horton & McMichael 2008; OECD 2008b; WHO 2005b).

GLOBAL RESPONSES TO ECOLOGICAL DEGRADATION TO IMPROVE HEALTH

Reducing the release of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and related compounds is an international success story. These compounds have been found to reduce the ozone layer of the upper atmosphere, which shields the surface of the earth from ultraviolet radiation from the sun. If the ozone layer continues to thin, then the intensity of ultraviolet radiation (UV) will continue to rise. The increased intensity of UV has impacts starting from the destruction of phytoplankton which is the base of the oceanic food chain right through to an increase in skin cancer and cataracts, and depressing the immune system in humans. The Montreal Protocol (UNEP 2000) shows what can be done with enough political will. The Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer is an international treaty designed to protect the ozone layer by phasing out a number of destructive substances such as CFCs. It is hoped that the ozone layer will be back to normal by 2015 but this depends on bringing the current black market in halons and CFCs in developing regions under control (Boyden 2005).

VULNERABLE POPULATIONS, SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE

The burden of disease is not shared equally and environmental degradation will most affect those who are socially vulnerable. The iceberg analogy presented in Chapter 1 (Figure 1.4) can be used again here. At the very bottom of the iceberg are the ecological and social determinants that underpin the health of entire populations and future populations. Children, frail aged and those who are poor, pregnant or have pre-existing diseases are affected most by environmental degradation (OECD 2008b). For example, the metabolic activity in children is higher than in adults and their bodies react differently when exposed to pollutants. Older people do not cope as well with temperature change. It is suggested that rural, regional and remote communities will be exposed to greater climate extremes and there may be even less access to fresh water and food supplies than there is now (Horton & McMichael 2008). Planning from now on will need to consider large numbers of environmental refugees. Underpinning health promotion practice with the principles of Primary Health Care will be crucial.

… the processes through which past societies have undermined themselves by damaging their environments fall into eight categories, whose relative importance differs from case to case: deforestation and habitat destruction, soil problems (salinization, erosion and soil fertility losses) water management problems, overhunting, over fishing, effects of introduced species, human population growth, and increased per capita impact of people.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree