E

Eating disorders

Description

Eating disorders are primarily psychiatric disorders and occur more often in women. Men are also at risk, but are less likely to seek treatment because eating disorders are perceived to be a women’s disease.

Patients with eating disorders may be hospitalized for fluid and electrolyte alterations; cardiac dysrhythmias; nutritional, endocrine, and metabolic disorders; and menstrual problems. A number of nutritional problems associated with these disorders require you to implement a nutritional plan of care.

The three most common types of eating disorders are anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder.

Anorexia nervosa

Anorexia nervosa is characterized by self-imposed weight loss, endocrine dysfunction, and a distorted psychopathologic attitude toward weight and eating. Anorexia nervosa is a serious mental illness affecting 1.2% to 2.2% of people during their lifetime, and it occurs more frequently in women.

Anorexia nervosa clinically manifests as abnormal weight loss, deliberate self-starvation, intense fear of gaining weight, lanugo (soft, downy hair covering the body except the palms and soles), refusal to eat, continuous dieting, hair loss, sensitivity to cold, compulsive exercise, absent or irregular menstruation, dry and yellowish skin, and constipation. Signs of malnutrition are noted during the physical examination.

Diagnostic studies often show iron-deficiency anemia and an elevated blood urea nitrogen level that reflects marked intravascular volume depletion and abnormal renal function.

Interdisciplinary treatment must involve a combination of nutritional support and psychiatric care. Nutritional rehabilitation focuses on reaching and maintaining a healthy weight, normal eating patterns, and perception of hunger and satiety.

Hospitalization may be necessary if the patient has medical complications that cannot be managed in an outpatient therapy program. Nutritional repletion must be closely supervised to ensure consistent and ongoing weight gain. Refeeding syndrome is a rare but serious complication of behavioral refeeding programs. The use of EN or PN may be necessary (see Enteral Nutrition, p. 709, and Parenteral Nutrition, p. 728).

Improved nutrition, however, is not a cure for anorexia nervosa. The underlying psychiatric problem must be addressed by identification of the disturbed patterns of individual and family interactions, followed by individual and family counseling.

Bulimia nervosa

Bulimia nervosa is a disorder characterized by frequent binge eating and self-induced vomiting associated with loss of control related to eating and a persistent concern with body image. Individuals with bulimia nervosa may have normal weight for height, or their weight may fluctuate with bingeing and purging. They may also abuse laxatives, diuretics, exercise, or diet drugs. They may have signs of frequent vomiting, such as macerated knuckles, swollen salivary glands, broken blood vessels in the eyes, and dental problems.

The cause of bulimia remains unclear but is thought to be similar to that of anorexia nervosa. Substance abuse, anxiety, affective disorders, and personality disturbances have been reported among people with bulimia.

■ Antidepressants are helpful for some but not all patients with bulimia. Education and emotional support for the patient and the family are vital. Support groups such as the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders (ANAD) (www.anad.org) are helpful to those affected by these disorders.

Binge-eating disorder is less severe than bulimia nervosa and anorexia nervosa. Individuals with binge-eating disorder do not have a distorted body image and are often overweight or obese.

Encephalitis

Description

Encephalitis is a serious, sometimes fatal, acute inflammation of the brain. It is usually caused by a virus. Many different viruses have been implicated in encephalitis; some of them are associated with certain seasons of the year and are endemic to certain geographic areas. Ticks and mosquitoes transmit epidemic encephalitis, whereas nonepidemic encephalitis may occur as a complication of measles, chickenpox, or mumps.

Clinical manifestations and diagnostic studies

The onset of infection is typically nonspecific, with fever, headache, nausea, and vomiting. It can be acute or subacute. Signs of encephalitis appear on day 2 or 3 and may vary from minimal alterations in mental status to coma.

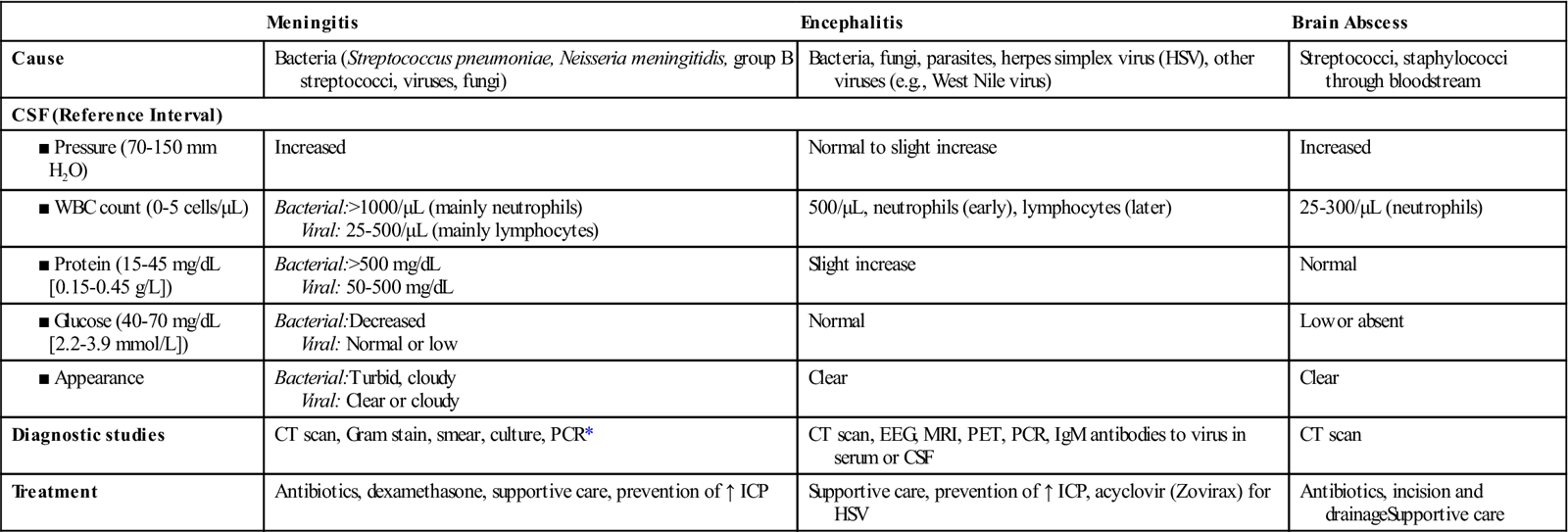

■ Diagnostic findings related to viral encephalitis are shown in Table 36.

■ Brain imaging techniques include CT, MRI, and positron emission tomography (PET).

Table 36

Comparison of Cerebral Inflammatory Conditions

| Meningitis | Encephalitis | Brain Abscess | |

| Cause | Bacteria (Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, group B streptococci, viruses, fungi) | Bacteria, fungi, parasites, herpes simplex virus (HSV), other viruses (e.g., West Nile virus) | Streptococci, staphylococci through bloodstream |

| CSF (Reference Interval) | |||

| Increased | Normal to slight increase | Increased | |

| Bacterial:>1000/μL (mainly neutrophils) Viral: 25-500/μL (mainly lymphocytes) | 500/μL, neutrophils (early), lymphocytes (later) | 25-300/μL (neutrophils) | |

| Bacterial:>500 mg/dL Viral: 50-500 mg/dL | Slight increase | Normal | |

| Bacterial:Decreased Viral: Normal or low | Normal | Low or absent | |

| Bacterial:Turbid, cloudy Viral: Clear or cloudy | Clear | Clear | |

| Diagnostic studies | CT scan, Gram stain, smear, culture, PCR* | CT scan, EEG, MRI, PET, PCR, IgM antibodies to virus in serum or CSF | CT scan |

| Treatment | Antibiotics, dexamethasone, supportive care, prevention of ↑ ICP | Supportive care, prevention of ↑ ICP, acyclovir (Zovirax) for HSV | Antibiotics, incision and drainageSupportive care |

CSF, Cerebrospinal fluid; ICP, intracranial pressure; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

*PCR is used to detect viral ribonucleic acid (RNA) or deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA).

West Nile virus should be strongly considered in adults older than 50 years who develop encephalitis or meningitis in summer or early fall. The best diagnostic test for West Nile virus is a blood test that detects viral ribonucleic acid (RNA).

Nursing and collaborative management

To prevent encephalitis, mosquito control should be practiced, including cleaning rain gutters, removing old tires, draining bird baths, and removing water where mosquitoes can breed. In addition, insect repellant should be used during mosquito season.

Management of encephalitis, including West Nile virus infection, is symptomatic and supportive. Initially many patients require intensive care. Acyclovir (Zovirax) and vidarabine suspension (Vira-A) are used to treat HSV encephalitis. For maximal benefit, antiviral agents must be started before the onset of coma.

Endocarditis, infective

Description

Infective endocarditis (IE) is an infection of the endocardial surface of the heart. The endocardium is the innermost layer of the heart and heart valves. Therefore IE affects the valves. An estimated 10,000 to 15,000 new cases of IE are diagnosed in the United States each year.

Classification

IE can be classified as subacute or acute.

IE can also be classified based on the cause (e.g., IV drug abuse, fungal endocarditis) or site of involvement (e.g., prosthetic valve endocarditis).

Pathophysiology

The most common causative agents, Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus viridans, are bacterial. Other pathogens include fungi and viruses.

IE occurs when blood flow turbulence within the heart allows the causative organism to infect previously damaged valves or other endothelial surfaces. This can occur in individuals with a variety of underlying cardiac conditions, including prior endocarditis, prosthetic valves, acquired valve disease, and cardiac lesions. A variety of invasive procedures (e.g., IV drug abuse, renal dialysis) can also allow large numbers of organisms to enter the bloodstream and trigger the infectious process.

Vegetations, the primary lesions of IE, consist of fibrin, leukocytes, platelets, and microbes, which adhere to the valve surface or endocardium. The loss of portions of this vegetation into the circulation results in embolization. Systemic embolization occurs from left-sided heart vegetation, progressing to various organs (e.g., kidney, spleen, brain) and extremities causing limb infarction. Right-sided heart lesions embolize to the lungs, resulting in pulmonary emboli.

The infection may spread locally to cause damage to valves or their supporting structures. This results in dysrhythmias, valve dysfunction, and eventual invasion of the myocardium leading to heart failure (HF), sepsis, and heart block.

At one time rheumatic heart disease was the most common cause of IE. However, now it accounts for less than 20% of cases. The main contributing factors to IE include (1) aging (more than 50% of older people have aortic stenosis), (2) IV drug abuse, (3) use of prosthetic valves, (4) use of intravascular devices resulting in health care–associated infections (e.g., methicillin-resistant S. aureus [MRSA]), and (5) renal dialysis.

Clinical manifestations

The clinical manifestations are nonspecific and can involve multiple organ systems. Low-grade fever occurs in more than 90% of patients.

Nonspecific manifestations include chills, weakness, malaise, fatigue, and anorexia. Arthralgias, myalgias, abdominal discomfort, back pain, weight loss, headache, and clubbing of fingers may occur in subacute forms of endocarditis.

Vascular manifestations include splinter hemorrhages (black longitudinal streaks) that may occur in the nail beds. Petechiae, which may result from fragmentation and microembolization of vegetative lesions, are common in the conjunctivae, lips, buccal mucosa, and palate and over the ankles, feet, and antecubital and popliteal areas. Osler’s nodes (painful, tender, red or purple, pea-size lesions) may be found on the fingertips or toes. Janeway lesions (flat, painless, small, red spots) may be found on the palms and soles. Funduscopic examination may reveal hemorrhagic retinal lesions called Roth’s spots. Onset of a new or changing murmur is frequently noted, with the aortic and mitral valves most commonly affected.

Clinical manifestations secondary to embolization in various body organs may also be present. These include: