Chapter 8. Drugs affecting the alimentary tract

At the end of this chapter, the reader should be able to:

• explain how to prevent and treat specific oral infections

• list the treatments for acid reflux and describe how acid and pepsin are produced

• understand the causes of peptic ulcer and aims of treatment

• discuss the antacids and the problems associated with their use

• give an account of the drugs used to treat chronic inflammatory bowel disease

• list the various classes of purgatives and appreciate the dangers associated with their inappropriate use

• describe how to diminish peristaltic activity with drugs

• discuss the significance of the liver in the use of drugs

The mouth

Salivation

A proper flow of saliva is necessary to keep the mouth fresh and free from infection. Salivary flow will be diminished in fever and dehydration and also by certain drugs, notably those of the phenothiazine group and the tricyclic antidepressants. Antimuscarinic drugs such as atropine will also diminish salivation. Severe oral infection may supervene if salivary flow is markedly decreased. This was a frequent complication in very ill patients in former times when dehydration was not adequately corrected and measures to ensure oral hygiene not practised. Patients receiving cytotoxic drugs are especially at risk as their resistance to infection is lowered and some cytotoxic drugs cause ulceration of the mouth.

Prevention of oral infection

• Avoid oral infection during surgery

• Avoid dehydration

• Use mouthwashes.

Before major surgery or any other procedure with a special risk of oral infection, the mouth should be inspected and infected gums or teeth treated. The help of a dentist or dental hygienist may be needed. Dehydration must be avoided and several topical treatments are available.

Mouthwashes

Thymol

Mouthwash solution tablets contain thymol, a mild antiseptic, and are adequate for most patients. One tablet is dissolved in a glass of warm water and used three or four times daily. For patients at special risk, various regimens can be used.

Chlorhexidine gluconate

A slightly more powerful antiseptic, chlorhexidine gluconate is used in a 0.2% solution ( Corsodyl). The mouth is rinsed out two to three times daily with 10 ml for about 1 minute. The tongue and teeth may be stained brown, but this can be largely avoided by brushing the teeth before use. Chlorhexidine 1% dental gel is useful for children and handicapped patients. Mouthwash solution can be used every 2 hours in between.

Artificial salivas

If dry mouth is a special problem, various artificial salivas are available, instead of or as well as mouthwash solutions. These include Glandosane and Luborant. In unconscious patients the mouth should be cleaned regularly. Sodium hydrogen carbonate one-quarter teaspoonful in 50 ml is particularly valuable for clearing mucus. (Note that sodium bicarbonate is also called sodium hydrogen carbonate and has the chemical formula NaHCO 3.)

Hydrogen peroxide

In some hospitals hydrogen peroxide is used to remove debris from ulcers, etc. In seriously ill patients the care of the mouth is a particularly important aspect of nursing care. Hospitals using different regimens and nurses will have to draw their own conclusions as to the most effective treatments.

Oral infections and ulceration

In spite of care, some patients will develop infections in the mouth; those receiving cytotoxic drugs are at special risk. The main infections are:

• Candida

• oral herpes simplex

• herpes labialis

• non-specific stomatitis with/without ulceration

• aphthous ulceration

• infections of the pharynx and tonsils.

Candida

This is common and is best treated by nystatin, an antifungal antibiotic (see p. 332), which is not absorbed from the intestine. Pastilles of nystatin are dissolved in the mouth four times daily after food; or a suspension can be used. Some patients find the taste unpleasant. Treatment should be continued for 48 hours after symptoms have resolved. An alternative is to use amphotericin, another antifungal antibiotic, as lozenges, four to eight times daily. Dentures must be removed during treatment and should be soaked in 1% sodium hypochlorite solution overnight and rinsed before being replaced.

In young children, miconazole gel smeared round the mouth is easier, but expensive.

Oral herpes simplex

For this problem, aciclovir suspension is used.

Herpes labialis (cold sores)

This must be treated when symptoms (local burning) just develop. There is no ideal remedy. Aciclovir 5% cream, corticosteroid cream or ice cubes applied locally have all been tried with some success. Aciclovir cream’s effectiveness may be enhanced if it is applied as soon as symptoms appear.

Non-specific stomatitis with/without ulceration

• Dehydration, if present, should be corrected.

• Chlorhexidine mouthwashes should be used as described above.

• Hydrogen peroxide can be used to cleanse ulcers.

• Benzydamine mouthwash ( Difflam), which acts as a local anaesthetic, is extremely effective in relieving the discomfort of oral ulceration. The mouth should be rinsed out every 2–3 hours with the undiluted solution. If this causes stinging, a 50:50 diluted solution should be used.

• Choline salicylate ( Bonjela) is a mild local anaesthetic in gel form that may be applied before meals and at night.

Aphthous ulceration

These small, painful, recurrent oral ulcers are common in healthy people. The cause is unknown, but may be related to stress, and treatment is only partly effective. Hydrocortisone pellets dissolved in the mouth four times daily or tetracycline mouthwashes are used.

Infections of the pharynx and tonsils

Infections of the pharynx and tonsils are very common and are usually viral. Most of them require no specific treatment, since recovery is rapid. Many people use gargles, although there is little evidence that they do any good. Compound thymol glycerin, a mild antiseptic, is popular and does no harm. Soluble aspirin is also used as a gargle. It is doubtful whether it has any effective local action but when swallowed will rapidly produce its systemic analgesic and anti-inflammatory effect.

Serious throat infections require the use of the appropriate antibiotic given systemically and there is little indication for the local use of antibiotics in these circumstances.

The oesophagus

Acid reflux and treatment

The following drugs are used:

• Gaviscon

• Gastrocote

• Mucaine

• histamine H2 receptor blockers

• proton pump inhibitors

• metoclopramide

• domperidone

• cisapride.

Inflammation may occur at the lower end of the oesophagus; it is usually due to reflux of acid from the stomach, and may be associated with a peptic ulcer (see below). Antacids and drugs that block the release of gastric acid can relieve it. Preparations are available which combine an antacid with a local anaesthetic and these are particularly valuable in relieving the pain of swallowing.

Gaviscon and Gastrocote are combinations of an antacid with alginates, which float on the gastric contents. If reflux occurs, they protect the mucosa of the lower oesophagus.

Mucaine contains the antacids aluminium hydroxide and magnesium hydroxide with oxetacaine, a local anaesthetic, which, it is claimed, relieves the pain arising from the inflamed oesophagus. If reflux is severe and persistent, more active treatment is used. This requires reducing gastric acidity and increasing the motility of the lower oesophagus.

Histamine H 2 receptor blockers (see p. 110) can be combined with antacids, but are less effective than in the treatment of peptic ulcers.

Proton pump inhibitors (see p. 110) abolish gastric acid secretion almost entirely and are more effective; they are used in severe cases of reflux oesophagitis.

Metoclopramide, which is a drug that stimulates oesophageal motility and thus keeps the oesophagus empty, is also useful. Metoclopramide (see p. 110) is the first choice, but adverse effects may preclude its use. Alternatives are domperidone or cisapride, which are free from central adverse effects, although cisapride has a number of potentially dangerous interactions with other drugs.

The stomach

The stomach is a hollow organ receiving food from the oesophagus and passing it on to the intestines after a variable interval of between 4 and 6 hours. It is concerned with the mechanical breaking down of the food to render it more easily digested and more easily absorbed. Its muscular walls are capable of powerful waves of peristalsis, which mix and macerate the food. The mucosa lining the stomach secretes hydrochloric acid and pepsin, which together initiate the digestion of proteins.

Dyspepsia and peptic ulcers

Dyspepsia, which is commonly called indigestion, is discomfort or pain in the abdomen or lower chest after eating. It may be accompanied by nausea and vomiting and is usually ascribed to disordered digestion.

Peptic ulcers are lesions of the lining (mucosa) of the stomach (gastric ulcer), the duodenum (duodenal ulcer) or of the oesophagus (oesophageal ulcer). One or a combination of the following may cause them:

• excessive secretion of hydrochloric acid and pepsin

• breakdown of the protective mechanism of the mucosa

• a microorganism, Helicobacter pylori.

Hydrochloric acid, which is produced to excess in duodenal but not in gastric ulcers, is responsible for the pain, and for many years the use of antacids was the mainstay of treatment. The whole approach to the healing of ulcers has changed with the discovery that infection of the stomach lining by the organism H. pylori is a major cause of them.

Infection of the lower part of the stomach (the antrum) increases acid production. This acid passes to the duodenum and the combined effect of acidity and damage to the mucosa gives rise to duodenal ulceration and prevents healing. Infection of the body of the stomach is a frequent cause of gastric ulcers and may also lead to gastritis and gastric carcinoma. Eradication of this infection results in healing of the ulcer.

Other factors may be involved, the most important being the resistance of the lining of the stomach to acid and pepsin. Prostaglandin E 2, which is formed in the stomach, reduces acidity and helps in the secretion of a layer of mucus which coats and protects the gastric lining. If the production of prostaglandin E 2 is inhibited by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs; (see p. 149), the protection is lost and ulcers are liable to develop.

The production of acid and pepsin

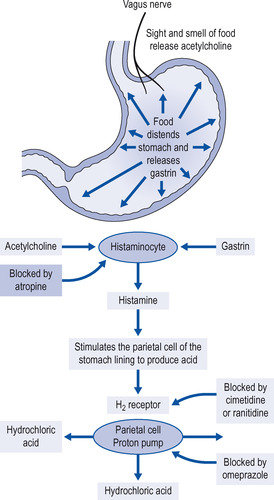

Acid secretion is a complex process. There are two ways in which it can be provoked (Fig. 8.1):

• Stimulation of the vagus nerve leads to the release of acetylcholine and thus to increased secretion of acid. In healthy people with an intact gastric mucosa, this is brought about by the thought, sight or smell of appetizing food. Adequate acid and pepsin are thereby produced to start the digestion of food when it arrives in the stomach. In patients with ulcers, the acid causes the typical pain, particularly if the hoped-for food is delayed.

• Distension of the stomach (for instance by food) causes the production of the hormone gastrin, and this in turn stimulates the stomach to produce acid.

|

| Figure 8.1 The mechanisms involved in the secretion of acid into the stomach and the effect and site of action of H 2 blockers. |

The common factor in acid production by both these mechanisms is the release in the stomach wall of histamine from cells called histaminocytes. Histamine in turn stimulates the proton pump in the parietal cells, which causes the release of acid in the stomach. The secretory effect of histamine on the stomach is mediated by H 2 receptors.

Treatment of peptic ulcers and dyspepsia

Approach to the treatment of peptic ulcers

Reducing acidity and protecting the ulcer from acid will relieve the pain of duodenal ulcer and will heal the majority of ulcers, but relapse within a year is very common (75%) unless the associated H. pylori infection is eradicated (see below). It is probably advisable, as demonstrated by Case History 8.1, always to test early for the presence of H. pylori. Reducing acidity and eliminating infection is achieved by reducing acid secretion (usually by a proton pump inhibitor) and using a combination of antibacterials (see below). This will cure the majority of patients but a few will require further treatment.

For gastric ulcers the initial treatment may be either with H 2 blockers or the eradication of infection, if present. After the treatment of gastric ulcers, repeat endoscopy is essential to eliminate the possibility that the ulcer may be malignant. Ulcers due to NSAIDs usually respond to an H 2 blocker or omeprazole. For a patient who is at a high risk of developing an ulcer – for example, the elderly, those with a previous history of an ulcer, or those taking high-dose NSAIDs – omeprazole may be co-prescribed. These approaches are summarized in Figure 8.2.

|

| Figure 8.2 Flow diagram of the management of gastric and duodenal ulcers. |

Drugs for reducing acidity

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access