Chapter 10 Disease control and management

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

understand the differences in definitions of chronic condition and chronic disease between the World Health Organization and the Australian Government

understand the differences in definitions of chronic condition and chronic disease between the World Health Organization and the Australian Government describe an integrated approach to chronic disease management, and what the elements of that approach might be

describe an integrated approach to chronic disease management, and what the elements of that approach might beIntroduction

Infectious diseases are also a common and significant contributor to ill health throughout the world. In many countries, this impact has been minimised by the combined efforts of preventative health measures and improved treatment methods. However, in low-income countries, infectious diseases remain the dominant cause of death and disability. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that infectious diseases (including respiratory infections) still account for around 23% (or around 14 million) of all deaths each year, and result in over 4.6 billion episodes of diarrhoeal disease and 243 million cases of malaria each year (WHO 2008).

In addition to the high level of mortality, infectious diseases disable many hundreds of millions of people each year, mainly in developing countries, with the global burden of disease from infectious diseases estimated to be around 300 million DALYs (disability-adjusted life years) (WHO 2008).

Defining chronic conditions and chronic disease

Chronic condition and chronic disease can be defined differently. Chronic condition ‘encompasses disability and disease conditions that people may “live with” over extended periods of time, for example more than six months’ (Flinders Human Behaviour and Health Research Unit (FHBHRU) 2009). They are amenable to generic approaches because there are generic self-management tasks regardless of diagnosis (FHBHRU 2009). Chronic disease is a subset of chronic conditions and refers to a specific medical diagnosis. It may be more likely to have a progressively deteriorating path than other chronic conditions (FHBHRU 2009; WHO 2002). In this chapter, the term chronic disease will be used. Chronic diseases are those involving a long course in their development or their symptoms. They account for a high proportion of deaths, disability and illness and are a major health problem worldwide. Yet many of these diseases are preventable, or their onset can be delayed, by relatively simple measures.

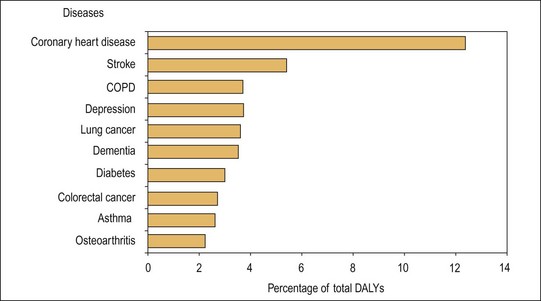

For a number of reasons, including the fact that people are living to older age, chronic diseases have increased in prevalence over the past century and today they affect one in four Australians. Most chronic diseases are generally not curable. Some can be immediately life threatening, such as heart attack and stroke; others are often serious, including various cancers, depression and diabetes. They all persist in an individual through life. They are, however, not always the cause of death. Chronic diseases are listed as the top 10 causes of the burden of disease in Australia. These diseases alone account for nearly 43% of the total disease burden in Australia (Fig. 10.1) (AIHW 2008, 2010).

Fig. 10.1 Top 10 leading causes of disease burden in DALYs* terms, Australia, 1996.

(Source: Mathers et al. AIHW 1999)

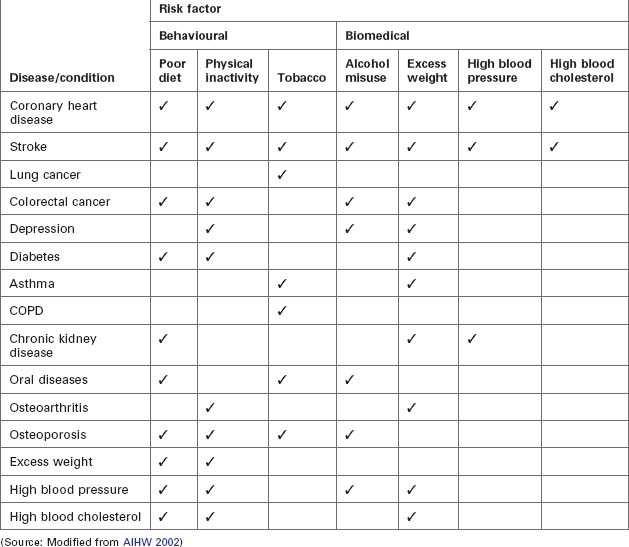

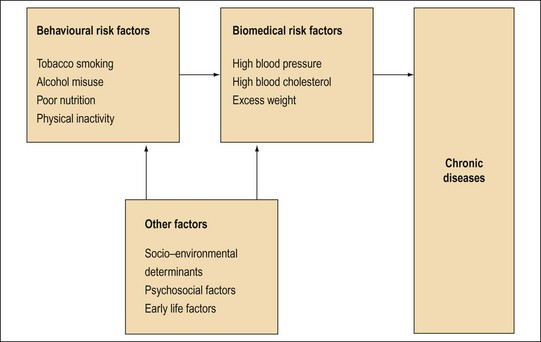

There are a number of behaviours that can prevent or delay the development of many chronic diseases, such as controlling body weight, eating nutritious foods, avoiding tobacco use, controlling alcohol consumption and increasing physical activity. Figure 10.2 illustrates a number of risk factors that contribute to the onset, maintenance and prognosis of many chronic diseases. In this figure, these are classified as ‘behavioural risk factors’, ‘biomedical risk factors’ and ‘other factors’.

Fig.10.2 Behavioural risk factors, biomedical risk factors and other factors contributing to chronic disease.

(Source: Modified from AIHW 2002)

Most of the chronic diseases have multiple risk factors and are considered to be ‘adult’ behaviours and conditions; however, the situations that lead to their initiation often begin early in life, or even in the womb. Therefore, it is important to have a lifecourse perspective of chronic diseases and their risk factors, one that recognises the interactive and cumulative impact of social and biological influences throughout life. Table 10.1 examines the relationship between risk factors and chronic diseases in Australia. It clearly points out the strong relationship between a range of behavioural and biomedical risk factors and chronic diseases (AIHW 2008, 2010).

The success of public health initiatives, in part, mean that people are living longer (National Health Priority Action Council (NHPAC) 2006; WHO 2002) and this increased life span allows more time for chronic illness to develop (AIHW 2002; AIHW 2010, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2003; NHPAC 2006, National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) 2001; National Public Health Partnerships (NPHP) 2001). Chronic diseases place an extra burden on health care systems and it is predicted that by the year 2020 chronic diseases will be the leading cause of disability in the world, with over 70% of the global burden of illness mainly attributable to CVD (cardiovascular disease, covering all diseases and conditions of the heart and blood vessels), cancer, diabetes and chronic respiratory diseases, as well as mental health problems, injuries and violence (AIHW 2002; AIHW 2010; CDC 2003, NHMRC 2001; NHPAC 2006; NPHP 2001; WHO 2002, 2005a). Similar to the WHO, Australia acknowledges chronic disease as a major health challenge (AIHW 2006; Australian Chronic Disease Prevention Alliance (ACDPA) 2004).

Continuum of care/integrated approach to chronic disease

In 2005, the NHPAC (2006) reviewed the national and international evidence for strategies for preventing and managing chronic disease and endorsed the National Chronic Disease Strategy (NCDS). The NCDS concentrates on four key areas for improving outcomes for people with chronic diseases: prevention across the continuum, early detection and treatment, integrated and coordinated care, and self-management (NHPAC 2006). Such a comprehensive approach incorporates the entire population continuum, from the ‘healthy’, to those with risk factors, through to people suffering from chronic conditions and their complications. Supporting this approach is the amendment, and relaxation of qualification criteria, for the Chronic Disease Management Plan (formerly the Enhanced Primary Care Plan) that provides funding for a more multidisciplinary management plan for patients with chronic conditions and/or complex care needs and more preventive care for older Australians (DoHA 2006).

Chronic disease prevention is an approach to health care that emphasises the maintenance of independence and continuing health. Prevention of chronic diseases follows a continuum of care ranging from prevention strategies directed at minimising or eliminating future chronic illnesses, with initiatives such as smoking cessation, healthy eating and physical activity programmes (Australian General Practice Network 2010). Furthermore, public health has a place in managing chronic diseases, as there are two main types of prevention – avoiding the development of chronic disease and delaying the expected complications of existing chronic diseases through good-quality treatment and management (WHO 2005b).

Public health and health promotion embrace an inclusive model, one that incorporates a population health perspective that views disease prevention and health promotion as a continuum (Pruitt & Epping-Jordan 2005). This position accentuates the whole scope of care, from primary prevention for healthy populations to early detection and intervention for subgroups considered at risk, through to management, tertiary prevention, rehabilitation and palliative care for people with established disease (AIHW 2002, 2010; NHPAC 2006; Pruitt & Epping-Jordan 2005; WHO 2005b).

Disease management programmes

Disease management programmes are a comprehensive approach to enhancing the quality of care for people with chronic diseases (Velasco-Garrido et al. 2003). They use evidence-based criteria of care, coordinate care through multicomponent and multidisciplinary programmes, and focus on the entire path of chronic conditions. Although there is no generic model suitable for all conditions, Velasco-Garrido et al. (from Kesteloot 1999) identify seven major components of chronic disease management:

Within Australia, there are now a variety of programmes addressing the management and prevention of chronic diseases; these are outlined under the NCDS’s four action areas for preventing and reducing the burden of chronic disease (NHPAC 2006). It should be noted that many of these interventions are multifaceted and, therefore, could be categorised in two or more of the action areas that follow.

Early detection and early treatment

Early detection and treatment can reduce complications, comorbidities and mortality. In Australia, only about half of the people with diabetes have been diagnosed and treated (NHPAC 2006). There are two primary approaches to early detection and treatment: population-based screening, and opportunistic screening by health workers for risk factors and/or early signs and symptoms (NHPAC 2006). Examples of the former include mammography for women aged 50–69, and bowel cancer screening, while the latter includes, for example, the ‘Go for your life’ programme in Victoria. This programme, in part, aims to detect people with pre-diabetes (impaired glucose tolerance and impaired fasting glucose) and to provide support for lifestyle changes to decrease the risk of diabetes developing (Department of Human Services 2006).

Integration and continuity of prevention and care

Integration and continuity of prevention and care includes care planning and coordination through a range of providers and settings (NHPAC 2006). For example, the chronic disease management (CDM) items available through Medicare for patients with chronic conditions and complex care needs; these include diabetes, heart disease and other chronic conditions (DoHA 2006). The CDM items cover a range of allied health workers, including exercise physiologists, diabetes educators, nutritionists, Aboriginal health workers and podiatrists (DoHA 2006).

Self-management

Self-management entails a person’s active involvement in his or her own health care. An important component of self-management is cooperation between the person, their family, health service providers and the health care system (FHBHRU 2009; Holman & Lorig 2000; Lorig et al. 2001; NHPAC 2006; WHO 2005b) (Case Study 10.1).

Case Study 10.1 Example of self-management

One example of a self-management programme is the federal Department of Health and Ageing’s Sharing Health Care Initiative (SHCI) demonstration projects, aimed at evaluating different approaches to chronic disease self-management. Through grant funding, the SHCI aims to enhance the quality of life for people with chronic diseases and their communities; to improve care providers’ appreciation of the advantages of self-management and advance collaboration between care providers, people with chronic conditions and their families; and to improve the effectiveness of health service utilisation. Initial outcomes include a decline in depression, pain and general distress; improved symptom management; and a fall in general practitioner visits and hospitalisations (Department of Health and Ageing 2005). An example of the SHCI is the Pika Wiya Health Service, a chronic condition self-management project for diabetes, in South Australia. A camp for Aboriginal people introduced education on medication, nutrition, exercise, podiatry, renal disease and palliative care. Many Aboriginal people in this area also have other chronic diseases, such as heart disease, renal disease and asthma (DoHA 2005).

Chronic disease prevention and management – some issues

As indicated previously, health care systems generally focus on responding to acute episodic health conditions, consequently, they are inadequate for the ongoing care and management of those with chronic health problems (Glasgow et al. 1999; NHPAC 2006; NHMRC 2001; NPHP 2001; Weeramanthri et al. 2003; WHO 2002). Furthermore, a large proportion of funding for chronic disease management is directed at programmes that target comparatively restricted categories of populations, diseases or risk factors; therefore, managers of comprehensive chronic disease programmes need to ensure that programmes are integrated to reduce unnecessary duplication (CDC 2003).

Chronic diseases are often not seen as emergencies, as the benefits to the population or subpopulation may take a long time to become apparent (Brownson & Bright 2004; Yach et al. 2004). In addition, there may be a lack of risk-factor information and data regarding needs for specific communities or populations, and inadequate resources pledged to chronic disease management programmes (Brownson & Bright 2004). Both communities and individuals may also be more concerned about involuntary risk exposure, for example, toxic waste, than voluntary risk exposure, such as insufficient exercise (Brownson & Bright 2004).

Clearly, it is essential to coordinate realistic and comprehensive strategies to advance the Australian health system’s ability to provide comprehensive chronic disease prevention and management (AIHW 2010).

Defining infectious diseases

One out of every two people in low-income countries dies at an early age from an infectious disease. Most of these deaths should have been prevented. How can families, communities and countries reach their dreams with this burden? Healthy development removes these obstacles and helps individuals and countries achieve their full potential. If the world invests in priority strategies to fight infectious diseases, much of this death and suffering could be prevented. (WHO 1999 p i)

A communicable (or contagious) disease is one that can spread from one individual to another. In contrast, infectious diseases are diseases caused by pathogenic microorganisms, such as bacteria, viruses, parasites or fungi. More specifically, zoonotic diseases are infectious diseases of animals that can cause disease when transmitted to humans (WHO 1999).

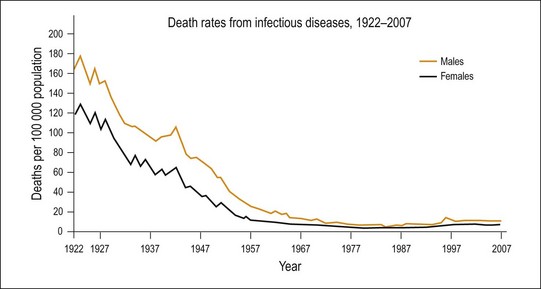

Infectious diseases are very common in developed countries and generally do not cause significant health outcomes in these communities. For example, some of the most common infectious diseases such as the common cold, dental caries and acne vulgaris have a highly significant economic and social impact, but do not have significant individual morbidity or mortality. In Australia, there are around 160 000 cases of infectious disease reported to health authorities each year (NNDSS 2010), but less than 1800 deaths. Deaths from infectious diseases have dramatically declined in Australia since the early part of the twentieth century, primarily due to improvements in sanitation and an improved quality of life. For example, in 1922 deaths from infectious diseases accounted for 15% of all deaths, but by 2007 they accounted for a little over 1% (AIHW 2010) (Fig. 10.3). In contrast, infectious diseases continue to be a major cause of death and disability in developing countries. For example, in South-East Asia infectious diseases account for 40% of deaths and 28% of illness and disability (WHO 2005c). Such countries often lack the economic capacity to provide the community with the public health infrastructure required to prevent or manage infectious diseases. Consequently, infectious diseases still account for five of the top ten causes of death in low-income countries (WHO 2007).

Medical microbiology

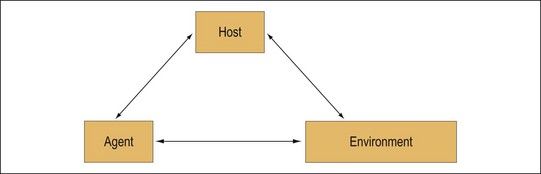

Medical microbiology describes the study of microbes that cause diseases in humans. The concept of human infectious disease is multidimensional and includes our interaction with the pathogen, the impact within our body of contact with the pathogen, and the interaction between our body and the various environments in which we live. For any infectious disease to occur, there are always three elements (Hurster 1997):

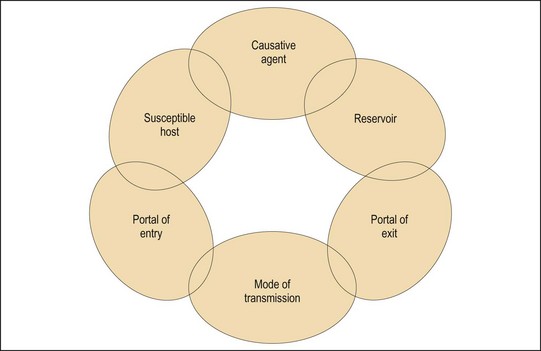

These interactions are commonly described in terms of two models of infectious diseases: the ‘agent–host–environment triangle’, which is also known as the ‘epidemiologic triad’, and the ‘chain of infection’ model (Figs 10.4 and 10.5).

Fig.10.4 Triangle model of infectious diseases.

(Redrawn from: Weber & Rutala 2001 p 4, adapted from APIC 1996 p 12)

Fig.10.5 Chain model of infectious diseases.

(Redrawn from: Weber & Rutala 2001 p 4, adapted from APIC 1996 p 18)

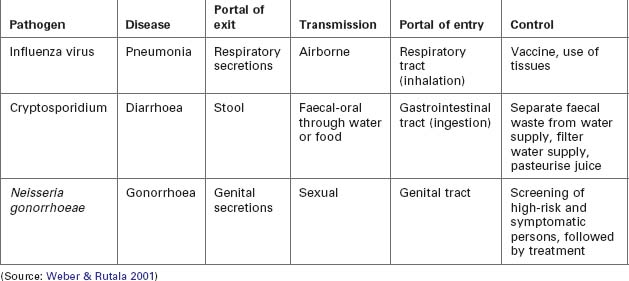

For the chain model of infectious diseases, the following elements must apply and these are illustrated in Table 10.2 (Weber & Rutala 2001):

Microorganisms

Microorganisms are all-pervasive. No drop of water, grain of soil or skin surface is free of microscopic organisms. These organisms may be characterised broadly in several categories (Irving et al. 2005).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree