Chapter 12 Disaster preparedness and public health

Defining disasters

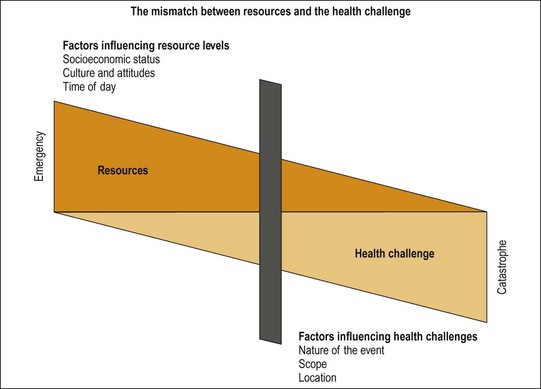

The extent of the challenge to the health and wellbeing of the community is determined by the nature of the event, its location, spread and impact, and by the characteristics and size of the community. The resources available to deal with the event are defined by the location, culture and socioeconomic status of the community and such variables as the time of day or day of the week. Thus, whether any single event or challenge to health and wellbeing is a disaster or not, depends on the influence and interaction of many factors. Figure 12.1 seeks to demonstrate the variable nature of this relationship. The slide on the scale marks a particular event, but its position on the scale is determined by those factors that influence the mismatch of resources and challenges to health.

Emergency Management Australia (EMA) defines a disaster as:

A serious disruption to community life which threatens or causes death or injury in that community, and damage to property which is beyond the day-to-day capacity of the prescribed statutory authorities and which requires special mobilisation and organisation of resources other than those normally available to those authorities (emphasis added). (Australian Emergency Manuals Series Part 1 1998)

Sundnes and Birnbaum (2003) described the context of disaster health as involving three essential domains: public health; emergency and risk management; and clinical and psychological care. Their conceptual map describes the interrelationship between these domains within a broader framework defined by community preparedness, response capability and resilience, political and social structures and the support resources available. The focus of this discussion is mostly on the public health domain.

Context

Epidemiology

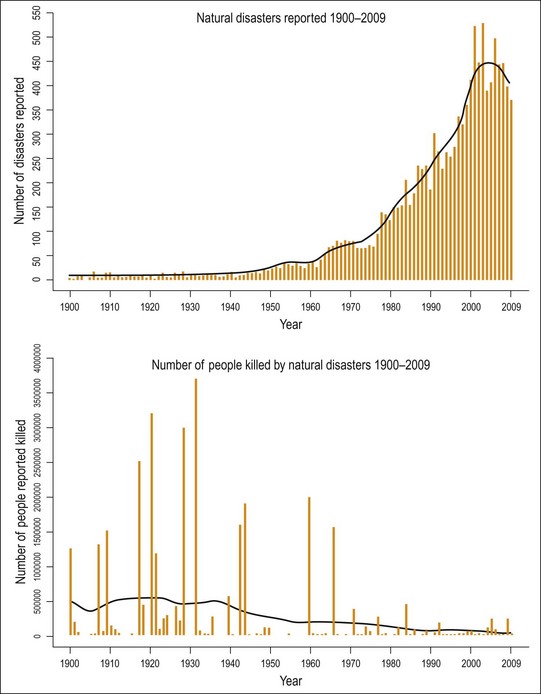

The number of recorded natural events and the number of people affected by those events continues to increase (WHO CRED 2009). Figure 12.2 demonstrates the number of events and the number of people killed in disasters over the last century. What this figure demonstrates is that the while the number of events has increased, the recorded number of people killed has declined.

Fig. 12.2 Trends in incidents and deaths.

EM-DAT: The OFDA/CRED International Disaster Database – www.emdat.net – Université catholique de Louvain – Brussels – Belgium.

Why are the events increasing? It is unclear whether the apparent increase is merely an increased level of recording. It is difficult to understand why the number of natural events would be increasing except where the effect of human intervention may be contributing to an increase in the frequency or severity of events. In particular, it has been suggested that global warming is contributing to the increased frequency and severity of cyclones (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2007), and deforestation may be contributing to the frequency of mudslides and forest fires.

Each day over 19 000 people attend hospital emergency departments (EDs) in Australia (Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision 2011). Australia has never had a single event with 19 000 casualties, yet every day we manage those numbers in our EDs. The difference between a quiet day and a busy day would exceed any major event to have confronted Australia. Thus, the cornerstone of our emergency health response arrangements should be the systems and structure, which characterise and respond to the daily burden of emergency health.

Health impacts

The health impacts of disasters may be categorized into two dimensions:

For example, the health impact of floods has been categorised into immediate, mid term and long term by Du et al. (2010). Direct effects of floods are those related to exposure to the water or debris contained within the water. Thus, drowning and injury are direct immediate consequences. On the other hand, floods often disrupt transportation or industry, leading to longer-term economic constraints, and the health consequences of poverty. Finally, the loss and grief that may accompany the flood, or the impact that the flood has on society, can have a long-term affect on an individual’s mental health.

Health is involved in such events in two ways:

Principles of disaster management

An engaged and prepared community

Risk-based approach

Hazards have been categorised by the World Association for Disaster and Emergency Medicine (WADEM) into natural, man-made and mixed hazards (TFQCDM/WADEM 2002):

Natural hazards are those arising from the natural environment.

Manmade hazards are those derived from the human environment.

All-agencies approach

A more effective approach is for all agencies involved in preparation and response to major incidents to operate on the basis of similar and standard approaches. Approaches such as those outlined in the Major Incident Management System (MIMS) (Hodgetts & Porter 2002) help with definition of roles and responsibilities, and the determination of the standard principles of action. In addition, the efforts of national standard setting bodies such as Emergency Management Australia (EMA), and its interaction with similar international bodies, allows for consistency in approach.

Comprehensive approach