STROKE SYSTEM OF CARE DEFINED

A system of health care delivery represents the continuum of services offered to a patient or a population of patients (Institute for Healthcare Improvement [IHI], 2014). Within the United States, the development of systems of health care across geographical settings and for specific patient populations is currently conducted within the context of the IHI Triple Aim Initiative: Health care should be delivered in a system that improves the health of populations, improves the patient’s experience of care, and reduces the per capita cost of health care (IHI, 2014). Prior to the discovery of intravenous (IV) thrombolysis as a treatment for ischemic stroke in the mid-1990s, there was no need to have an organized system of care to identify stroke patients and to facilitate care once identified. Care for patients with stroke was largely supportive and not time-sensitive. However, IV thrombolysis is now available for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke and must be administered within hours of the start of a stroke. Therefore, early recognition and transportation of a stroke patient to a hospital capable of providing thrombolysis became a paramount concern once this treatment was available. The American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) quickly began initiatives to develop such a system for the treatment of stroke. The AHA/ASA defines stroke system of care (SSC) as a coordinated continuum of care that addresses all aspects of care, from primary prevention to activation of EMS, acute care, secondary prevention, rehabilitation, and reentry into the community (Silva & Schwamm, 2013).

Several initiatives were underway between 1997 and 2005 to develop a system of care for stroke patients. However, the best conceptualization of an SSC was published in 2005, when the AHA/ASA introduced their Stroke System of Care Model (SSCM). The model proposed that all citizens should have access to organized and expert stroke care regardless of geographical location or other socioeconomic disparities. Significant progress has been made over the past decade toward the development of an SSC. Efforts to organize care resulted in increased use of IV tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), improved patient outcomes, and reduction in mortality (Silva & Schwamm, 2013). However, stroke continues to be a time-sensitive condition that has limited acute interventions, which require a systematic approach to patient triage, workup, and intervention. This is further challenged by a need for coordination of speedy access to multiple resources and specially trained teams to treat patients emergently. IV thrombolysis remains underused in the treatment of ischemic stroke (Alberts et al., 2005; Gorelick, 2013). Although great progress has been made, as of 2010, only a slight majority of patients in the United States had access to hospitals with stroke expertise through EMS routing protocols, suggesting much work remains to fully realize the AHA/ASA SSCM (Gorelick, 2013).

Early efforts to develop stroke programs have focused on identification of resources necessary to provide stroke care, development of care pathways, and cohorting of patients on stroke units. Formalized stroke certification by external organizations has continued to improve care by setting a minimum standard of program organization and evaluation, and rigorous evaluation process for any organization wishing to call themselves a stroke center. The definition of relationships between hospitals and the best organization of services in an SSC has evolved over years. However, the AHA/ASA, in conjunction with the Brain Attack Coalition and the National Stroke Association, have converged on a model with three distinct levels of stroke centers in the United States (Gorelick, 2013).

DEVELOPING STROKE SYSTEMS OF CARE

DEVELOPING STROKE SYSTEMS OF CARE

After the approval of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) in 1996, there was an immediate need for integration of EMS as a key component of a successful SSC. The AHA/ASA and the National Stroke Association (NSA) have mobilized to develop and support efforts to improve symptom recognition, activation of 911 for EMS response, and the rapid treatment of stroke after hospital arrival (Gorelick, 2013). The NSA established in the mid-1990s the NSA Stroke Center Network program and developed foundational guidelines for the early recognition of stroke and delivery of EMS services to route patients to hospitals capable of providing emergent stroke care and thrombolysis. The Brain Attack Coalition formed shortly after and also worked to improve EMS services and the rapid detection and treatment of ischemic stroke.

The AHA/ASA, Brain Attack Coalition, and NSA continue to shape the delivery of organized stroke care through national advocacy efforts nearly a decade later. All three national societies support the concept of an SSC integrating care from prevention to acute treatment and rehabilitation. The attributes of an effective SSC include coordinated care, a customized system that fits local environment needs, use of available resources and programs with an emphasis on continual performance improvement, and quality assurance (Silva & Schwamm, 2013). The importance of coordination between the various components of a stroke system is essential and remains challenging because it spans usual lines of demarcation for medical care, reimbursement, and government jurisdiction as we now define it (Higashida et al., 2013). However, the development of a U.S. SSC to date attempts to coordinate care across care settings despite the barriers.

Brain Attack Coalition

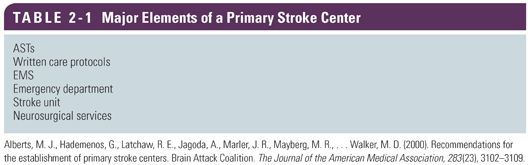

The Brain Attack Coalition (BAC) provided foundational guidance for the development of an SSC and continues to guide the stroke field through recommendations on the development and organization of stroke care. The BAC is a multidisciplinary group composed of representatives from a number of major professional organizations involved in delivering stroke care. The BAC provided the initial framework for the formal development of a tiered stroke system in the United States through the publication of consensus papers with recommendations for organizing stroke care services (Alberts et al., 2000; Alberts et al., 2005). The BAC initially proposed the development of primary stroke centers (PSCs) as hospitals that offered organized stroke care 24 hours a day (Alberts et al., 2000). In this initial paper, the BAC surmised that organized stroke care in PSC hospitals would have a direct and measurable positive impact on the mortality and morbidity after stroke. A PSC would offer rapid assessment of a patient with stroke symptoms and access to stroke experts capable of providing thrombolysis to patients with ischemic stroke in a timely fashion. Beyond thrombolysis in the first few hours of ischemic stroke, the PSC would also coordinate early rehabilitation services and initiate secondary preventive measures according to the best evidence in managing patients with stroke (Alberts et al., 2000).

After the BAC’s introduction of the PSC model, The Joint Commission (TJC), in collaboration with AHA/ASA, established minimum structural elements, standards of care, and performance measures to guide hospitals in developing a PSC program. In 2003, TJC began certifying PSCs, thus providing national recognition for centers demonstrating compliance with national standards, PSC recommendations, clinical practice guidelines, and ongoing performance improvement activities (Fonarow, Smith, Saver, Reeves, Bhatt, et al., 2011). Since the initial TJC certification in 2003, the PSC certification program has continued to grow, with approximately 1,600 centers currently certified as of 2014 (TJC, 2014a).

In 2005, the BAC published a second consensus paper calling for a second tier of stroke certification for centers that specialized in the surgical management of patients with ischemic stroke, ICH, and SAH. This new tier of stroke centers would be called comprehensive stroke centers (CSCs), and the recommendations outlined the interprofessional coordination of care necessary for the most acutely ill patients with stroke (Alberts et al., 2005). A CSC would incorporate neurosurgical services, endovascular services, and cardiovascular surgery services when appropriate with neurological services in the hospital. This additional tier of stroke certification recognized that not all PSC centers could offer neurosurgical, endovascular, and other advanced programs of care around the clock. A CSC represented concentrated and highly cost and time-intensive services. This model was similar to the trauma system in place in the United States and familiar to many EMS providers and community leaders. In 2013, TJC finalized the standards and performance measures for CSCs and began certifying organizations. As of 2014, 73 centers in the United States had successfully completed initial CSC certification (TJC, 2014b).

In 2013, the BAC proposed a third tier of stroke centers to complete the model of the AHA/ASA SSCM. The third tier is the development of acute stroke–ready hospital (ASRH), where the most immediate and stabilizing stroke care could be provided and then patients would be mobilized to either a PSC or CSC as needed (Alberts et al., 2013). The development of a formal certification program by TJC or other external certifying bodies has yet to be developed.

Stroke program certification has played a key role in the development of an SSC in the United States by organizing care within a hospital. Beyond hospital certification, the development of regionalized models to dictate how EMS interacts with CSCs is also shaping the delivery of acute stroke care in the United States. This has included development of local and regional EMS regulations to route acute stroke patients to PSCs. By the end of 2010, it was estimated that 53% of U.S. population was covered by routing protocols (Song & Saver, 2012).

The evolution of organized stroke care has now spanned almost two decades with a stroke center model promoting use of structured care protocols and continuous performance improvement/quality assurance that spans the entire care continuum. Many parallels can be made to the currently developed trauma model of care delivery. Shared experiences can also be traced to the development of regionalized resources for heart attack and cardiac arrest centers. These multifaceted time-sensitive emergencies all share a similar need for coordination of care, public and EMS collaboratives, and ongoing care delivery system improvements. Data evaluating the impact of developing stroke programs in hospital suggest this model is improving stroke care. There are multiple studies that validate the efficacy of stroke units and stroke programs within hospitals in providing care to patients with acute stroke. In comparison to patients cared for in general medical units without a focus on stroke care, patient cared for in stroke units had up to a 28% reduction in mortality, a 7% increase in being able to return to home, and an 8% reduction in length of stay (Candelise et al., 2007; “Collaborative Systematic Review,” 1997; Langhorne et al., 2013).

Although the tiered system of stroke care is the current model for delivering stroke care in the United States, the relationship between stroke centers has yet to be fully defined. The PSC level of care remains the most common stroke center certification in the nation and allows the most citizens access to general stroke care and thrombolysis when appropriate. Theoretically, all PSCs should then work with a CSC who would care for the most acutely ill stroke patients in need of the most intensive services. However, the types of patients who should receive care at a CSC versus a PSC and facilitating the timely transfer of patients remain undefined.

In addition to external certification, many states in the United States have developed policy and legislative initiatives guiding the regional routing of patients with stroke by EMS to only hospitals capable of providing care, such as a certified center (L. Schwamm et al., 2010). This is commonly referred to as state designation of stroke centers and regional routing protocols. The initiative to include state legislators in the development of regional stroke systems began in the early 2000s after the Stroke Treatment and Ongoing Prevention (STOP Stroke) Act failed to gain bipartisan support at a national level in 2003 (L. Schwamm et al., 2010). Regional AHA/ASA representative then began grassroots efforts at a regional and state level to influence the development of EMS routing protocols for stroke patients. As of 2013, over half the states in the United States have legislation guiding the designation of stroke hospitals and subsequent EMS routing of patients with stroke, with several additional states currently considering such legislation (Gorelick, 2013).

American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Establishment of Stroke System of Care Model

In 2005, the AHA/ASA conveyed a multidisciplinary group, the Task Force on the Development of Stroke Systems, to describe the state of stroke care fragmentation at the time and to define key components of a stroke system and recommend methods for implementation of a stroke system (L. H. Schwamm et al., 2005). This task force of experts in areas of stroke prevention, EMS, acute stroke treatment, stroke rehabilitation, and health policy development conducted an extensive review of stroke literature and developed the SSCM. Using a systems approach to stroke care, it was identified that the care delivery model in most areas of the United States failed to provide an integrated coordinated means of providing stroke prevention measures, acute treatment, and rehabilitation. The group identified key components of an SSC, including the development of stroke centers as already outlined earlier. However, the SSCM conceptualized care beyond a stroke center across the stroke continuum of care. Seven key components were identified as necessary to coordinate and promote patient access including the following:

● Primordial and primary prevention

● Community education

● Notification and response of EMS

● Acute stroke treatment, including hyperacute and emergency department processes

● Subacute stroke treatment and secondary prevention

● Rehabilitation

● Continuous quality improvement activities

Primordial prevention referred to interventions designed to decrease the development of disease risk factors and have broad impacts on health, whereas primary prevention referred to the strategies used to manage known disease risk factors. A well-organized SSC would include efforts to prevent stroke from ever occurring through such prevention strategies. Community education was also recognized as a critical element of an SSC, and the SSCM emphasized the need for increased awareness of stroke symptoms by the general community, timely presentation to a stroke center for treatment when a stroke occurred, and better adherence to risk reduction regimens.

The SSCM also recognized the key role of EMS in an organized SSC (L. H. Schwamm et al., 2005). Effective notification and response of EMS for stroke involves complex communication between the public, EMS programs, and hospital emergency departments. The field recognition of stroke symptoms, priority dispatch of EMS providers, triage, and transport to appropriate facilities require definition and coordination between the EMS services and the receiving hospital.  The model further recognized the importance of an interprofessional hospital-based acute stroke team (AST). The AST coordinates stroke care from arrival to discharge and requires ongoing training, supporting rapid identification, diagnosis, and initiation of acute stroke therapies to patients presenting to the hospital. The AST should operate using written protocols that outline evidence-based interventions, appropriate resources, and clearly delineate roles of hospitals and team members.

The model further recognized the importance of an interprofessional hospital-based acute stroke team (AST). The AST coordinates stroke care from arrival to discharge and requires ongoing training, supporting rapid identification, diagnosis, and initiation of acute stroke therapies to patients presenting to the hospital. The AST should operate using written protocols that outline evidence-based interventions, appropriate resources, and clearly delineate roles of hospitals and team members.

Finally, an SSC should include organized and standardized efforts to provide subacute care after hospitalization, with focus on risk factor reduction and prevention of poststroke complications. Stroke rehabilitation should be provided to optimize neurological recovery, including teaching compensatory strategies, relearning activities of daily living and skills required for community reintegration. Each phase of care in the SSCM should operate using a systems approach to stroke care and use continuous quality improvement strategies to improve patient care processes and outcome. Process and outcome metrics should be identified through evidenced-based methods or driven by national consensus. Building stroke systems in the United States is the next step in improvement of stroke outcomes in prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation of stroke (L. H. Schwamm et al., 2005).

The AHA/ASA Task Force on the Development of Stroke Systems made the following general recommendations:

● Stroke systems should ensure effective interaction and collaboration, promote organized care, and identify performance measures to evaluation stroke systems.

● Care coordination requires development of tools to be used for stroke prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation.

● Decisions need to be based on what is in the best interest of the stroke patient and may require collaboration among entities transcending geopolitical or corporate affiliations.

● Stroke system should identify and address potential obstacles to implementation.

● The system should be customized for each state, region, and locality with recognition of universal elements and should bridge disparities such as rural and neurologically underserved areas (L. H. Schwamm et al., 2005).

COMPONENTS OF STROKE SYSTEMS OF CARE

COMPONENTS OF STROKE SYSTEMS OF CARE

Core Components of Certified Stroke Centers

All stroke centers, regardless of certification as a PSC or CSC, begin with some consistent structural elements that support the overall operations that are needed to provide stroke patient care. The initial coordination of services for a stroke program begins with the EMS team providing the first contact for medical care (The role of EMS in supporting stroke care is fully described in Chapter 4). A stroke program in a hospital must have a relationship with area EMS. This relationship includes the level of knowledge the EMS workers have related to stroke recognition and initial care, inbound communication, and handoff to the hospital team. Both the EMS and hospital stroke program must determine the necessary dedicated resources and administrative infrastructure needed between the EMS and the PSC or CSC (Alberts et al., 2000; Alberts et al., 2005).

The core recommendations for PSCs are organized around 11 aspects of stroke care and can be divided into direct patient care and support services (Tables 2-1 and 2-2) (Alberts et al., 2000). The core components listed for patient care have continued to offer an organizing framework and remains the building platform for both primary and comprehensive levels of care. The PSC continues to stabilize and provide emergency care to stroke patients 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. The CSC should offer the same services as a PSC as well as additional neurosurgical, endovascular, and critical care services for the most critical stroke patients that require advanced testing and intervention (Alberts et al., 2005). Development of effective notification of EMS and prehospital communication has been shown to increase the direction of patients to facilities equipped with the right resources to manage stroke emergencies. Further development of regional partnerships and use of telemedicine continues to afford more patient-aggressive interventions and improved patient outcomes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree