Chapter 9 Developing personal skills

Overview

People’s health behaviour or lifestyles have been regarded as the cause of many modern diseases. Therefore a main focus of health promotion has been on modifying those aspects of behaviour which are known to have an impact on health.

Enabling people to change is often assumed by health promoters simply to mean health education. Such programmes are described by Keleher (2007, p. 145) as typically delivered as brief interventions or in a series of sessions covering those things the clinician or health promoter regard as important with compliance as the goal.

Client-centred health education is concerned with a person’s agency in decision-making. Such an approach acknowledges that people can take some control over their lives through knowledge, skills and confidence and it may enable people to identify structural barriers and facilitators to their health. This kind of empowering education was described by Paolo Freire (see Chapter 10) in his description of radical adult literacy pedagogy. Frequently however developing personal skills is equated with helping people to change, drawing on psychological theories of behaviour change, motivation and self-efficacy.

Definitions

Attitudes

These are more specific than values and describe relatively stable feelings towards particular issues. There is no clear association between people’s attitudes and their behaviour. Sometimes changing attitudes may stimulate a change in behaviour and sometimes behaviour change may influence attitudes. For example, many people continue to smoke despite a negative attitude to smoking. Yet once the behaviour is stopped, they may develop vehement antismoking views.

People’s attitudes are made up of two components:

Festinger (1957) used the term cognitive dissonance to describe a person’s mental state when new information is given which is counter to that already held. This prompts the person either to reject the new information (as unreliable or inappropriate) or to adopt attitudes and behaviour which would fit with it.

Drives

The term ‘drive’ is used in the Health Action model (Tones & Tilford 2001) to describe strong motivating factors such as hunger, thirst, sex and pain. It is also used to describe motivations which can become drives, such as addiction. Some studies suggest that addiction is the consequence of frequently repeated acts which become a habit and its base is a psychological fear of withdrawal (Davies 1997). Social learning theory (Bandura 1977) uses the term instinct to describe behaviours which are not learned but are present at birth. Instincts can override attitudes and beliefs. Hunger, for example, can easily override a person’s favourable attitude and intention to diet.

How do you explain consistent findings in many studies that show a gap between knowledge and behaviour change, e.g. 70% of the population know about the importance of 5 a day but only 35% of the population act on it (Scottish Executive 2005)?

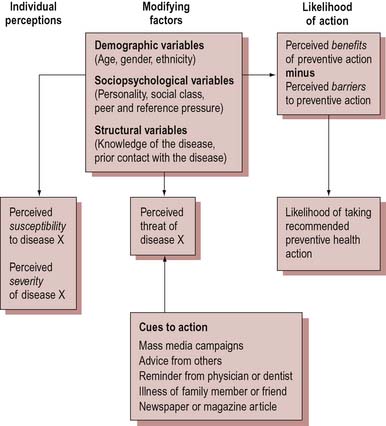

The health belief model

The Health Belief model is probably the best-known theoretical model highlighting the function of beliefs in decision-making (Figure 9.1). This model, originally proposed by Rosenstock (1966) and modified by Becker (1974), has been used to predict protective health behaviour, such as screening or vaccination uptake and compliance with medical advice (e.g. Gillam 1991). The model suggests that whether or not people change their behaviour will be influenced by an evaluation of its feasibility and its benefits weighed against its costs. In other words, people considering changing their behaviour engage in a cost–benefit or utility analysis. This may include their beliefs concerning the likelihood of the illness or injury happening to them (their susceptibility); the severity of the illness or injury; and the efficacy of the action and whether it will have some personal benefit, or how likely it is to protect the person from the illness or injury.

For a behaviour change to take place, individuals:

Where a situation is not well known however, people have an unrealistic optimism that ‘it won’t happen to me’ (Weinstein 1984).

There are over 250 000 traffic accidents each year with 30 000 casualties, of which 3400 are fatalities. Excess speed is a contributory factor in a significant number of road accidents. In one survey (Scottish Office 1998) 88% of drivers admitted to driving at 40 mph in a 30 mph zone at least sometimes. The current response to speeding is:

How might an understanding of social cognitions help to target a strategy for safer driving?

You may have considered people’s beliefs about:

Many health education campaigns have attempted to motivate people to change their behaviour through fear or guilt. Drink–drive campaigns at Christmas show the devastating effects on families of road accident fatalities; smoking prevention posters urge parents not to ‘teach your children how to smoke’. Increasingly hard-hitting campaigns are used amongst others to raise awareness of the consequences of binge drinking, smoking and drug use. Whether such campaigns do succeed in shocking people to change their behaviour is the subject of ongoing debate (see, for example, Hill et al 1998). Although fear can encourage a negative attitude and even an intention to change, such feelings tend to disappear over time and when faced with a real decision-making situation. Being very frightened can also lead to denial and an avoidance of the message. Protection Motivation theory (Rogers 1975) suggests that fear only works if the threat is perceived as serious and likely to occur if the person does not follow the recommended advice.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

BOX 9.1

BOX 9.1 BOX 9.2

BOX 9.2 BOX 9.3

BOX 9.3

BOX 9.4

BOX 9.4 BOX 9.5

BOX 9.5 BOX 9.6

BOX 9.6