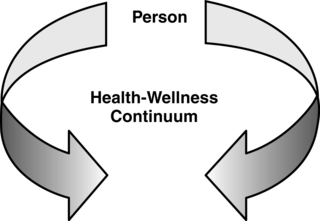

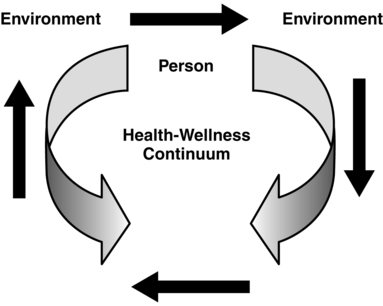

The development of curricula has historically been the responsibility of faculty, as they are the experts in their respective disciplines and the best authorities in identifying the knowledge and competencies graduates need to have by graduation. As the emphasis for designing relevant curricula continues to increase, so does the need to involve a broader community of stakeholders in the curriculum development process. Practice disciplines such as nursing are actively engaging a diverse array of stakeholders in curriculum design, development, implementation, and evaluation. The desire to increase engagement can and does add to the complexity of the development process and the ability to alter curricula in a timely manner. To address the need to create or change curricula to be responsive to workforce expectations requires faculty to develop curricula that are flexible in design, open to broader interpretation as expectations change, and capable of being implemented using a variety of different methodologies. This chapter is therefore about the tale of two approaches to developing curriculum. Traditionally, curriculum development has been built on the concepts of frameworks, objectives, and closely orchestrated learning experiences. This approach envisions curriculum development as a logical, sequential process. The focus of the logic and sequencing is on what faculty believe students need to know and the content that faculty believe is critical to their ability to do (Diekelmann, Ironside, & Gunn, 2005). The more contemporary approach shifts the emphasis from an epistemological to an ontological orientation (Doane & Brown, 2011). Students in an ontological approach become the focus of curriculum development (Benner, Sutphen, Leonard, & Day, 2010). This approach “highlights the way in which meaning, interpretation, and the knowledge translation process are being shaped by the student” (Doane & Brown, 2011, p. 22). Knowledge is then shaped by the individual student in the context of the learning environment of the moment. In today’s educational climate the value of education is measured against job marketability. In the discipline of nursing, emphasis has been placed on what knowledge and competencies graduates have on exit from their programs as it relates to the expectations of the roles into which they are hired. In response, nursing faculty have come to approach curriculum development from a product or outcomes perspective. This approach has been seen as a revolutionary departure from the traditional teaching process orientation used in the delivery of nursing curricula. Focusing on learning as the product, the emphasis is placed on what students know and can apply to changing and often uncertain situations. This approach assumes that both students and faculty have latitude in individualizing the learning experience and the processes used in creating that experience. Posner (1998) suggested that both process and product are critical to the development of curriculum by suggesting that there are “two necessary and complementary elements: curriculum development technique and curriculum conscience” (p. 96). He argued that curriculum development as a technique is a process that incorporates what we in nursing education see as the traditional approach that relies on theoretical models and frameworks. Curriculum conscience is described as the consequences of curriculum decisions made and assumes that the better decisions we make as faculty, the better the student outcome. The debate as to what curriculum is and should be most likely began with Plato (Grier, 2005) and it is not the intent of this author to challenge the prevailing thoughts. Therefore this chapter introduces faculty who are new to curriculum development to some of the classic building blocks as well as looking to the future of curriculum. This chapter describes the use of curriculum frameworks for the purpose of conceptualizing and organizing the delivery of the knowledge, values, beliefs, and skills necessary for professional nursing practice. Various factors that shape the process of curriculum development are discussed. Because curriculum development begins with the need to conceptualize the discipline of nursing, a discussion of organizing frameworks is presented (Grier, 2005). Also addressed are historical factors that have affected the design of nursing curricula, and the chapter ends with a discussion of outcomes and competencies and how they are related to faculty’s conceptualization of the discipline. Examples of outcomes and competencies illustrate the link between curricula, faculty expectations, and student learning. Although there are a number of definitions that fit an epistemological approach to curriculum, Glatthorn, Bosche, and Whitehead’s (2006) definition of curriculum as “the plans made for guiding learning, usually represented in retrievable documents of several levels of generality” (p. 5) fits nicely with the notion of knowledge as a shared meaning. A major step in this planning is determining the desired learning outcomes that should occur as a result of this planning process. Therefore a pivotal question for faculty to ask is: “What should students know and do on completion of their educational experience?” Given today’s environment of accountability, the issue of functionality is paramount. The need for accountability permeates all aspects of education, from primary through postdoctoral educational programs. Therefore it is critical to appropriately determine what competencies—in terms of knowledge, skills, and attitudes—students must successfully demonstrate at the completion of a program that will meet the expectations of a dynamically changing health care system. Faculty must also decide what learning experiences will facilitate students’ attainment of these competencies and how the attainment of these competencies will be evaluated (Boland, 2004). Accountability requires that curricula remain dynamic, especially as education faces the challenges of what seems like an exponential growth in knowledge, the impact of technology on how we teach and students learn, and the evolving and uncertain future of the health industry (Forbes & Hickey, 2009). The more contemporary or ontological definition of curriculum is determining the learning processes that “support students to develop confident and competent practice within the shifting, complex terrain of contemporary health care milieus” (Doane & Brown, 2011, p. 22). Knowledge becomes the background as curriculum is focused on engaging students in identifying, interpreting, and using knowledge as they become competent practitioners. Curriculum frameworks provide faculty with a way of conceptualizing and organizing the knowledge, skills, values, and beliefs critical to the design of a coherent curriculum plan that facilitates student learning and their achievement of the desired educational outcomes. The value of curriculum frameworks is in their ability to provide the base for developing expected nursing competencies. Organizing or conceptual frameworks “allow students to apply what was learned to new situations and to learn related information more quickly” (Tanner, 2007, p. 52). This is critical, as the majority of nursing curricula today are overloaded, with students being overwhelmed by the amount of knowledge faculty expect them to entrust to memory. Added to the complexity of curriculum development is the need to continue to address general education expectations and outcomes, which often are institutional specific. More and more emphasis is being placed on interdisciplinary learning and interprofessional collaboration and its impact on both undergraduate and graduate curricula. Today’s higher education environment is reemphasizing a strong general education foundation for all undergraduate and graduate students, and this orientation is having an impact on professional curricula that are already pinched for space and time. An example of this effort is noted in the “standards for success,” which were born out of a collaborative effort of the Association of American Universities and The Pew Charitable Trusts (2003). These standards tend to reflect lifelong learning skills that will continue to serve the learner as they move into a global workforce. These skills have been related to thinking critically, clearly expressing thoughts and ideas, clarifying their values, evaluating assumptions of self and others, and examining the evidence for thoughts and actions (Inderbitzin & Storrs, 2008). The Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) Future of Nursing report recommendations clearly speak to the need for more interprofessional educational didactic and practice learning experiences (IOM, 2010). The report challenges schools of nursing to integrate these collaborative learning opportunities into the curriculum. Also, nursing faculty cannot ignore the need to incorporate personal and social values along with the economics of an educated workforce in the development of curricula. As these external forces continue to prescribe critical elements that need to be included, nursing must find ways to meet expectations without continuing to add to already overloaded curricula. In determining what needs to be taught and learned within the context of the phenomenon of nursing, nursing itself must first be defined. The faculty’s philosophical beliefs about how teaching, learning, and the discipline of nursing should be viewed, described, and evaluated are often woven together into an organizing framework. This framework has historically guided the development of most nursing curricula (see Chapter 7). Organizing frameworks have been used in curriculum development to delineate the constructs embedded in a traditional philosophy statement that reflects the collective faculty belief. It is important that organizing frameworks not be construed as a permanent feature of a program but rather as a kaleidoscope of complex patterns related to what students need to know and how they will best learn it. Fawcett’s (1989) classic work on conceptual models and frameworks can provide readers with a discussion of theories, models, and concepts that is beyond the scope of this chapter. Organizing frameworks can be a means for creating access to knowledge about the phenomena of interest or importance to the discipline. Organizing frameworks do provide a logical structure for cataloguing and retrieving knowledge. This structure is essential to the processes of teaching and learning as faculty guide students in the development of cognitive linkages among knowledge to which they are exposed “which allows them to see patterns, relationships or discrepancies that are not apparent to novices” (Tanner, 2007, p. 52). Additionally, organizing frameworks can assist the learner in building a context for storing and retrieving nursing knowledge and helping to promote an understanding and application of knowledge to new or dynamic practice situations. The purpose in constructing frameworks is to systematically design a mental picture that is meaningful to the faculty and students when determining what knowledge is important and has value to nursing today and how that knowledge should be defined, categorized, and linked with other knowledge. Today’s critics of higher education are calling for the ability of graduates to be able to integrate knowledge and make application to complex and often uncertain situations. Ervin, Bickes, and Schim (2006) recognized that although the majority of nurses seek positions in acute care settings, there needs to be broader orientation to a continuum of care settings within a global context. This thinking is consistent with the recent IOM 2010 recommendation that tomorrow’s nurse be prepared to practice across a broad range of care settings. Organizing frameworks need to reflect both concepts relevant to populations and settings. In summary, organizing curriculum frameworks provide a blueprint for determining the scope of knowledge (i.e., which concepts are important to include in the teachers’ and learners’ mental picture) and a means of structuring that knowledge in a distinctive and meaningful way for faculty and students. A number of approaches are used in defining and shaping frameworks. However, an organizing framework must reflect the sphere of nursing practice, the phenomena of concern to nurses, and how nurses relate to others who are dealing with health concerns (Bevis & Watson, 1989; Warda, 2008). Organizing curriculum frameworks are the educational road maps to teaching and learning. As with any road map, multiple route options are available for arriving at a given destination or outcome. As faculty move toward the adoption of an outcome orientation in curriculum building, organizing frameworks or models will continue to serve the same purposes noted earlier but will be driven by philosophical views and futuristic mental pictures regarding the evolving practice of nursing. An example of an organizing framework that is shaping recent outcomes in baccalaureate curricula stems from the Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) project. Using its recommendations that “graduate nurses must have the knowledge to describe strategies for learning about outcomes of care, the skill to use quality measures, and the attitude to appreciate quality improvement” (Forbes & Hickey, 2009, p. 5), faculty are able to identify outcomes of the learning process for their institution. As increasing attention is being given to student learning, the emphasis on curriculum is transforming from teaching to learning. With this paradigm shift comes the need to look at theories and frameworks focused on learning. The concepts of emotional intelligence (Dekker & Fischer, 2008; Fischer et al., 2005) and transformational learning (Mezirow, 1991; Taylor, 2008) are now being considered by faculty as they develop curriculum. One traditional approach to constructing an organizing framework is to use a particular nursing theory or model to help shape the visual image that is consistent with the philosophy of the faculty. For example, if faculty believe that “health encompasses conditions known as disease and that it is an expansion of a person’s consciousness” (Newman, 1997, p. 22), faculty will probably adopt Newman’s theory of health as the vehicle for organizing knowledge for that particular nursing program. However, if faculty believe that caring is at the core of nursing, Watson’s (1997) theory of caring might better serve when explaining the discipline to students and cataloguing knowledge about the discipline of nursing. The advantage to building an organizing framework on a single theory or model is the ability to use a single image with a defined vocabulary that is shared by both the learner and the teacher. Drawing further on Watson’s theory as an example, she says that “the transpersonal caring relationship and authentic presencing translate into ontological caring competencies of the nurse, which intersect with technological medical competencies” (Watson, 1997, p. 50). The image put forth in this description is “transpersonal caring relationship,” which is at the core of Watson’s theory. “Ontological caring competencies” and “technological medical competencies” evolve from this caring relationship. It is the development of these competencies that students would be expected to demonstrate in a program in which Watson’s theory guided the knowledge to be learned and determined the expected performances of the program’s graduates. Using a single theory or existing conceptual model has limitations and poses challenges. One theory or model may not reflect everybody’s visual image or view of nursing and nursing practice. This becomes problematic when faculty have developed or been educated in curricula that have used a different theory or orientation to the discipline (Webber, 2002). Forbes and Hickey (2009) suggest that the use of only one theory in a framework limits the ability of faculty to pull together all elements of their curriculum, which provides a rationale for moving away from this approach. Given the challenges and limitations of using a single theory as an organizing framework, faculty choice does not have to be constrained by a single theory or model. Those who believe that a combination of many theories or concepts is more reflective of their beliefs about nursing may use an eclectic approach to developing a curricular framework. For example, an eclectic framework might include the concept of nursing as defined by Florence Nightingale, the concept of needs as defined by Maslow, the concept of self-care as defined by Orem, and the concept of a caring relationship as defined by Watson (Fawcett, 2000). All are critical concepts, but each concept comes from a different theory or theoretical orientation. Historically, accreditation standards and performance expectations have had a significant impact on many organizing frameworks as faculty have moved to incorporate or add into their organizing frameworks and curriculum models such concepts as critical thinking, problem solving, communication, caring, diversity, and therapeutic nursing interventions (McEwen & Brown, 2002). Although these concepts can be compatible with the essence of nursing, they are often not defined well enough to be consistently used by the teacher or applied by the learner. Faculty adopting an outcome orientation to curriculum must be able to construct the context and meaning that these outcomes will have in the curriculum structure. Critical thinking is one outcome that most undergraduate programs have adopted. A number of nationally normative tools have been created to measure critical thinking both on entry into and exit from a program. However, critical thinking as a cornerstone of an organizing curriculum framework is often not well defined, nor are its attributes identified for systematic and purposeful incorporation into nursing curriculum or assessment activities. Critical thinking is a skill, and without a nursing-oriented context to ground this skill, it is meaningless in and of itself. If the means is critical thinking, then faculty must determine the end in the development of the context. It is interesting to note that accreditation standards are moving away from prescribing expectations almost as quickly as these expectations were first embraced. As faculty move away from the more traditional use of theory or theories in designing curriculum frameworks, a number of unique designs have been identified. One interesting approach to an eclectic curriculum design is the KSVME framework (Webber, 2002). This framework is constructed around five “conceptual cornerstones”—nursing knowledge, nursing skills, nursing values, nursing meanings, and nursing experience (Webber, 2002, p. 17)—and incorporates many of the recognized concepts present in today’s nursing curricula. The healing web is another example of a collaborative effort to design an organizing framework whose conceptual orientation is woven into a “collaborative clinical practice in a differentiated practice model” (Nelson, Howell, Larson, & Karpiuk, 2001, p. 404). The healing web draws components from Newman’s health theory and Watson’s caring theory to construct the essential building blocks of this “transformative model” (Nelson et al., 2001). The emancipatory curriculum, designed to focus less on structure and content and more on the dynamic of learning through discovery, dialogue, and critical reflection, is yet another approach to creating a more meaningful educational experience (Diekelmann, Ironside, & Gunn, 2005; Schreiber & Banister, 2002). Although this curriculum design was conceived as the antithesis of the traditional structured curriculum designs, it is still anchored in philosophical conceptualizations from phenomenology, feminist theory, and critical social theory (Schreiber & Banister, 2002, p. 41). Challenges to a more individualized approach to curriculum structure can vary depending on individual faculty beliefs, experiences, and priorities. The Quality and Safety Education in Nursing: Enhancing Faculty Capacity has developed a quality and safety framework that is being used to revise or is being incorporated into existing curriculum frameworks. This work began in 2005 through Robert Wood Johnson Foundation funding and the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) holding regional meetings designed to facilitate the incorporation of this framework into prelicensure programs (AACN, 2010). The Oregon Consortium for Nursing Education (OCNE) model is gaining in popularity across the country and has a number of elements believed to address some of the challenges in nursing education today (OCNE, 2006). An example of a simplistic curriculum structure may include the concepts of health, person, and environment. As shown in Figure 9-1, if health has been defined as a continuum, with wellness at one end and illness at the other, the mental picture is very simple. Adding the concept of person to this model requires that person first be defined. If a person is believed to have the ability to balance wellness and illness to achieve a high level of wellness, an additional dimension could be added to the model as depicted in Figure 9-2. When the concept of environment is incorporated into the image, it creates additional complexity. If we define the environment as an external force that affects a person’s ability to balance his or her state of wellness along the health continuum, shown in Figure 9-3, person and health occur within the context of an open environment, and the environment that is wrapped around the person affects the person’s ability to balance his or her wellness state. These examples demonstrate how busy a framework can become when concepts are added. Again, with increasing emphasis on learning it is critical that the learner and learning become visible in curricular models or conceptual maps. As nurse educators we have spent the majority of our time attending to issues surrounding discipline-related knowledge. Today our lens must include the process by which learners are motivated to learn, how they construct what they are learning, and how they transport that learning into meaningful thoughts and actions (Taylor, Fischer, & Taylor, 2009). Clancy, Effken, and Pesut (2008) describe complex systems as being constructed from a “highly connected network of entities from which higher order behavior emerges” that they believe has significant implications on how we think about learning and the practice of nursing (p. 249). The assumptions growing out of the work related to complex systems support the need to focus on learning and the integration of the student both in the knowledge being taught and in the process in which the knowledge is learned and used. An updated view of a nursing framework can be seen in the complex adaptive system model proposed by Chaffee and McNeill (2007). For graduate education, the Nurse Educator Pathway Project is an example of competencies that faculty identified from their nurse educator program. These competencies are the “ability to demonstrate knowledge of and engagement with educational theories; fosters effective teaching and learning relationships; facilitates learning and creates effective learning environments; understands and works with multiple complexities related to learning; advances nursing professional practice; and demonstrates leadership abilities” (Young et al., 2010, p. 6). There appears to be a rebirth of the integrative curriculum that gained popularity in the 1960s and 1970s. An integrative curriculum is designed to integrate knowledge from more than one discipline (Spelt, Biemans, Tobi, Luning, & Mulder, 2009). This curriculum approach focused on concepts perceived as critical to the practice of nursing. They often were drawn from a variety of theories or theoretical models and provided the foundation on which the curriculum was constructed. Today there is growing interest in core concepts as a focal point of curriculum construction (Giddens & Brady, 2007). The transformative curriculum is also gaining in popularity as more and more faculty are investing in learning. A transformative curriculum is based on the idea of students having a big-picture view of what they are learning (connective reality), having the opportunity to interact with the knowledge in a critical and reflective way (engagement), and being encouraged to construct meaning and actions appropriate to their learning (command of information). An example that supports the ideas of transformative curricula is embedded in the “learning centered curricula” proposed by Candela, Dalley, and Benzel-Lindley (2006), in which student learning becomes the focal point of the curriculum. Recognition of patterns is a critical outcome that one hopes faculty can achieve in the development of curriculum frameworks and students can obtain as they move through the program. The resulting framework or model must present a “gestalt” of the nursing theory or models from which the concepts are taken. It is critical that faculty and students grasp an understanding of the framework without an intensive investment of time and energy. Csokasy (2002) suggests that “to maintain curriculum integrity, it is critical that faculty design all curricular activities to reflect the selected philosophical framework” (p. 33). The cornerstones of all frameworks must be reviewed on a regular basis to ensure continued relevance to the education and practice of nurses. Lindeman (2000) suggests that “nurse educators must prepare nurses for the emerging health care system and not the system of the past or one that they wish were in place” (p. 7). This is truer today than ever as health care systems are operating in an uncertain, ambiguous, and changing environment. The National League for Nursing Education Advisory Council Competency Work Group (2010) has developed an integrated curriculum model that speaks to what is perceived as changes in education to complement the changes in a dynamic health care system.

Developing curriculum: frameworks, outcomes, and competencies

Curriculum defined

Curriculum frameworks as a building block

Purposes of organizing frameworks in curriculum development

Developing an organizing framework for curriculum

Developing a single-theory framework

Developing an eclectic framework

Examples of nontraditional curricular frameworks

Designing a graphic of the framework

Guiding principles for developing a curriculum framework

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access