Introduction

A portfolio is more than a record of events, experiences and developments in our careers. It is a vital, ‘living’ document that has a secure and respected place in continuing professional development (CPD), and within mechanisms for professional regulation. It also encourages us to make sense of what we are doing and to learn through reflection. Developing a portfolio will enable you to (Palmer, 2000):

■ celebrate your achievements

■ target your professional development

■ develop your skills of learning from professional and personal experiences

■ make decisions for the future based on your knowledge of the past.

However, whilst portfolios comprise an integral aspect of contemporary learning, CPD and professional regulation (Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC), 2008a), it does not necessarily mean that everyone feels positive about keeping one. It is important to identify and acknowledge your thoughts and feelings about this process, as you might have taken a minimalist approach to this; or you may have thrown your heart and soul into keeping a portfolio because you have always had a tendency to write about your everyday experiences as a way of understanding yourself and the world around you; or like most readers, you may be somewhere in between. As Hull et al. (2005) note, many healthcare professionals are unsure of the practical issues related to compiling a portfolio. They also tend to attach only a tenuous link between the documentation in portfolios, and portfolio learning.

This chapter offers a practical guide to portfolios through an analysis of what they are, why we need them, what the benefits of keeping them are – in particular in relation to portfolio learning, which is also associated with keeping up to date. It acknowledges the likely reservations related to portfolios, explores ways of developing and maintaining your portfolio, and how they are assessed. To assist you with your learning, as you read through this chapter, connections are made with other relevant chapters in the book.

What are portfolios and profiles?

This section defines the term portfolio, distinguishes it from profiles, and discusses two principal ways of keeping and presenting portfolios and profiles, namely as hard copies and as electronic copies (e-portfolio).

Definitions and distinctions

For healthcare professionals busy in the world of practice and for student nurses and midwives the issue of portfolios and profiles may initially appear confusing, raising such questions as ‘Why do I need one?’, ‘What do I put in them?’ and ‘How often should I input items into them?’. Sensible enough questions, given the terminology and ‘jargon’ that tends to proliferate when new concepts about learning are introduced to the professional workplace. It is always useful to begin with the basics and to gain an understanding and appreciation of what such concepts are concerned with, and what the expectations are for both you and the profession.

A portfolio is a collection and recording of the individual’s learning experiences and activities that demonstrate their personal and professional development, and achievements. Keeping a portfolio therefore allows you to document your learning and achievements, which can be done on paper or electronically. Such a record also makes it easier to explain your achievements whenever appropriate, as it is a flexible and yet comprehensive account of your professional development and how further development will be accomplished.

A profile is an extract or an adaptation of one’s portfolio that contains elements that have been deliberately selected for a specific event (such as for a job interview), for supplying evidence of professional development to the professional regulatory body or for making the case for gaining credit points as part of a university course; this will take the form of Accreditation of Prior Learning (APL), or Accreditation of Prior Experiential Learning (APEL) (see Chapter 14). Your curriculum vitae (CV) that is adapted for a specific purpose is therefore also a profile.

Types of portfolio

Various forms of portfolio are available for the healthcare professional to obtain and use as they are, or to adapt to include their personal preferences. They can be kept as hard paper copy compilations and/or as electronic copy, usually referred to as e-portfolio.

Paper (hard copy) portfolios

Examples of hard paper copies of portfolios that can be purchased include The Churchill Livingstone professional portfolio (Kenworthy and Redfern, 2004), A professional portfolio for dietitians (British Dietetic Association, 2001) and various others available on the worldwide web (e.g. Health Professions Council (HPC), 2008). Some healthcare trusts also provide their employees with a portfolio to facilitate recording of continuing and mandatory professional updating. However, increasingly most healthcare professionals now tend to keep an electronic version of their portfolio that is updated whenever significant learning occurs, and it can be printed when required, and kept in a folder containing corresponding original documents such as certificates, testimonials and awards, which also constitute ‘evidence’ of learning.

For pre-registration nursing and midwifery students, their universities tend to provide them with a portfolio that they have to maintain as part of their pre-qualifying educational preparation programmes. The structure of these portfolios tends to be informed by research findings and guidelines from regulatory bodies (e.g. NMC, 2006). For learning from experiences, input tends to comprise a guided step-by-step pro-cess that ends with a reflective question asking the user what they have learnt from the experience. This is the most crucial component of reflective recording in portfolios, and is often followed by a further development plan.

e-portfolios

Increasingly, e-portfolios are being used particularly in profession or vocation linked courses. In some employment-related modules, students have to submit an e-profile (i.e. an extract from their e-portfolio) for summative assessments. One example of e-portfolio is Pebblepad (University of Wolverhampton, 2008), which has been in use since 2005. The publishers indicate that over 100000 users have Pebblepad accounts, including over 40 institutions and a number of personal purchasers. Tools in e-portfolios allow for inclusion of photos (e.g. of certificates) and of videos (of presentations made by the portfolio owner) for instance.

The Pebblepad e-portfolio can, for instance, be used for recording CPD and personal development plans (PDP) and progress with them, which can be used for demonstrating conformance with standards, such as those required by professional regulatory bodies for revalidation of the individual’s professional qualification.

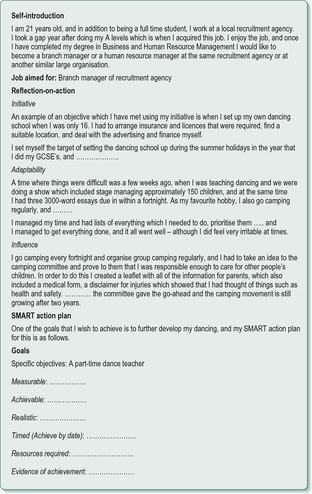

An example of an e-profile submitted for summative assessment by Laura, a second-year BSc in Business and Human Resource Management student, is as follows. Laura had agreed to study for one short module in each of the 3 years of her course as a condition of being accepted on the course, which focuses on enhancing her chances of gaining employment straight after gaining her degree. The assessment for her second-year module, entitled Management and teamwork in organizations, included submitting an e-profile comprising a 600-word script documenting: a brief self-introduction, the job aimed for, reflection and evidence of use or initiative, adaptability and influence, and a SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, timed) action plan. Figure 15.1 shows parts of the e-profile that Laura submitted as one of the two assessed components for the module.

Obviously, Figure 15.1 is a profile, i.e. extracts from Laura’s portfolio, that was presented for a specific purpose. As this example of e-portfolio illustrates, as with hard copies, an e-portfolio is more than a record of personal achievements because it is a ‘learning system’, in that it has provisions for writing up structured reflections on specific activities and experiences, and a record of aspirations and systematic forward planning.

e-portfolios also allow for certain items to be shared with selected individuals, or specific groups, or made public through the worldwide web. Other than for assessment purposes (formal or informal), over time, the e-portfolio user can store and review several ‘assets’ reflecting learning and achievement that can be presented for:

■ articulation: of learning from experience

■ application: for a place on a course, for funding

■ accreditation: by professional bodies

■ appraisal: by self, peer or 360 degrees feedback

■ advancement: job promotion or job transition.

Further instances of use of e-portfolios are as follows:

■ Research students can use e-portfolios to provide their supervisor with ongoing records of activities and accomplishments.

■ Art and design students keep portfolios of their designs, along with commentary from experts.

■ Students on overseas placements can confer with peers and their academic supervisors electronically with regards to validity of items for their portfolios.

■ Trainee teachers can send their lesson plans electronically to their academic supervisors, receive feedback, and document their teaching experiences.

■ Project sub-groups can share information and findings destined for their portfolios with other subgroups.

Furthermore, when students submit a profile or component of their e-portfolio for assessment, their teacher, mentor or supervisor can add feedback to the profile electronically. For summative work, moderators and external examiners can be given access to the profile for feedback and quality assurance purposes.

Research on the use of e-portfolios includes a study by Garrett and Jackson (2006), who evaluated the use of a mobile clinical e-portfolio by nursing and medical students, using wireless personal digital assistants (PDAs) with several useful functions, including helping to prevent the isolation of students whilst engaged in supervised clinical practice. The study found positive attitudes to the use of PDA based tools and portfolios.

Why do we need to keep a professional portfolio?

Why are you developing a portfolio? Is it to keep a record of your achievements, for professional development purposes, for accreditation of practice against university credit points, or because you have been told that you must do so?

Why are you developing a portfolio? Is it to keep a record of your achievements, for professional development purposes, for accreditation of practice against university credit points, or because you have been told that you must do so?Benefits and issues related to portfolios

Before we start discussing the reasons for keeping portfolios, consider and make detailed notes on what you feel are the advantages and disadvantages of keeping portfolios.

Before we start discussing the reasons for keeping portfolios, consider and make detailed notes on what you feel are the advantages and disadvantages of keeping portfolios.No doubt you will have noted various benefits of keeping portfolios, as well as some of the problematic aspects. The rationale for keeping a record of one’s achievements and learning in portfolios (and profiles) arises from a variety of pressures in the contemporary world of work.

One major influence has been the increasing trend towards work-based vocational and professional learning, where it is necessary to keep a portfolio as evidence of what is being learnt as a continuous process. Additionally, employers expect professionals to update themselves continually and to be life-long learners who change and grow as the organization changes and grows, and record their learning.

Furthermore, in the past, nurses have not always been forthright in valuing their contribution to the healthcare team or in marketing their skills effectively. Engaging in portfolio learning can be a useful stage in doing these, developing self-awareness and building confidence and professional insights.

Another influencing factor comprises some of the more recent educational theories and approaches such as experiential learning, self-directed learning (based on ‘adult education’ or andragogical theories advocated by Rogers (2007) for instance), problem-based learning as well as portfolio-based learning (see Table 15.1, below, and Chapter 12).These educational theories and approaches place the healthcare professional at the centre of an active process of learning, with individuals taking responsibility for identifying and reflecting on the diverse learning opportunities that they encounter.

| THEORY/APPROACH | APPLICATION |

|---|---|

| Experiential learning Concerns developing your problem-solving abilities, taking responsibility for your part in the learning process and learning from experience | Creating a desire to know more Involves thinking critically by challenging your assumptions and those of others. It includes identifying, planning and evaluating your learning opportunities |

| Reflective practice Concerns thinking about, mulling over and working through of ideas, issues and critical incidents | Developing abilities to integrate knowledge and find meaning within practice Involves exploring feelings and learning from practice by examining and recording actions, leading to new insights and effective practice |

| Professional learning support Concerns competent significant others who support and encourage us by being accessible and approachable. These are the mentors, preceptors andclinical supervisors who help us to reflect and assist our professional development | Working with critical friends Involves the building of enabling relationships that are built on mutual trust and respect to provide a supportive environment where we can consider our practice |

| Peer learning Refers to learning from other students on the same course, or colleagues of equal status at work | Working in formal or self-selected groups Group work, self-organized short-life self-directed study groups; learning from a buddy |

| Portfolio learning Concerns the regular maintenance of a portfolio that documents and draws together your experiences and provides further insights on practice | Working with your ideas and entries Writing up and engaging with the entries that allows you to demonstrate your personal and professional achievements in an organized manner, and which motivates towards further learning |

| Adult education/andragogy Refers to the specific ways in which adults learn, such as having clear goals about what they’d like to get out of the education programme, and seeing new learning in the context of their life experience | Having own learning plans Deciding what materials to study, when, who with and how; self-directed learning |

However, perhaps the strongest influence has emerged from professional regulatory bodies’ approach that individual registered practitioners are accountable for their own updating and life-long learning (NMC, 2008a). The NMC standard is that registrants maintain a personal and professional portfolio of their learning activities as evidence of CPD and comply with requests for a relevant extract of their portfolio for audit requirements (NMC, 2006, p. 8), albeit that Snow (2007) reported that such checks are currently on hold.

The Health Professions Council (HPC) requires all healthcare professionals on its register to undertake CPD as a legal requirement (HPC, 2007). The first audit of these standards started in 2008 with a random sample of 5% of chiropodists and podiatrists being the first audited to prove they met the HPC’s standards.

These influences have led to explorations and requirements to record learning and individual professional development as a meaningful process. It is generally agreed that this process should encourage further learning and facilitate professional accreditation. This accreditation is the process that offers recognition of the healthcare professional’s knowledge and professional competence against professional standards, and also as credit points towards a university award.

The need to help healthcare professionals make sense of learning experiences in practice settings (experiential learning), and to make connections with planned learning (courses, in-service training, conferences or workshops) is another reason. This is all in the context of increasing professional autonomy, public accountability and quality frameworks such as clinical governance.

Furthermore, research highlights the effectiveness and various benefits of portfolios. McMullan (2008) for instance explored the use of portfolios by pre-registration students with regards to learning during practice placements and found that they helped them in their development of self-awareness and independent learning. McColgan (2008) reviewed the literature to examine the value of portfolio building by registered nurses, and found that portfolios are highly valued as long as an organizational culture of learning and support from colleagues existed.

Portfolio learning

As was discussed earlier, it should be appreciated that a portfolio contains a tangible and recognizable record of learning involving collecting, writing up and analysing significant learning experiences, including planned (or structured) and incidental learning events. Portfolio development is concerned with reflecting on your experiences and making the links between personal experiences and insights, and professional practice (see Chapter 12 and Chapter 14).

Portfolio learning is much more than good record keeping, as it is more concerned with how you engage with your thoughts and ideas. It involves working through critical incidents, collecting the evidence, and analysing such learning opportunities for yourself (see Chapter 6). Thus, a portfolio provides a safe environment, controlled by you, where you can be free to:

■ acknowledge and build on your strengths

■ confront your weaknesses or fears

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access