In Table 3-1, the difference between the communications in column 2 (what was reported) and those in the third column (what a factual report would have been) may seem subtle, but they are hugely impactful to each of these situations. In column 2, the manager reported what was reported to him or her, as fact. Had the communication been passed on as portrayed in column 3, the factual information was about the report of an incident, not the assumption of the truth from that report. (If you doubt the importance of this difference, ask either an attorney or an ethicist which is the least risky, most accurate, most ethical way to pass on information, especially information that will result in a manager or other person taking some sort of action).

All of the reports in column 1 could have been 100% accurate. Or, they could have been inaccurate, either because of a deliberate (for whatever reason) bending of the truth or misperceptions of the original reporter. Good managers continually remind themselves that perceptions are often at the root of communication problems.

All three of the incidents listed in Table 3-1, column 1, are real issues that occurred in a community hospital where one of us worked. All three of the responses in column 2 were communications that resulted from them. When they were investigated, it was discovered that:

1. Jim had disagreed with Mary at a meeting where an entire group was voicing opinions about what their strategy should be. The other six people at the meeting stated that Jim never raised his voice but he did state he thought she was wrong. Mary was the only person who perceived him as “yelling” at her.

2. There was no way to verify the time it took to answer the patient’s call light. The time could have been more or less than the patient perceived it to be.

3. The Vice President for Finance did not have the same recollection of his conversation with the physician as the physician did. His memory of the hallway discussion was that the physician approached him and stated he was unhappy with the hospital’s decision not to buy another DaVinci Robot. The VP recalled stating that the hospital had determined that the return on investment for a third robot was negative and couldn’t justify buying another one, especially when capital is limited.

By accepting and reporting perceptions as fact, the individuals involved lost credibility when the circumstances were investigated. Their ability to communicate factually and fairly appeared to be impaired. (We are not implying that any of these three incidents should not be investigated for potential interpersonal, patient service, or relationship interventions. The issue here is appropriate reporting of nonwitnessed or verified information.)

It’s important that partners understand how each of them communicates. If one feels the other is not clearly and objectively communicating, he must be able to discuss this with him or her for the good of the partnership, the team, and the organization. Failing to address communication issues with a partner leads to more miscommunication. In fact, failure to communicate about any issue, misunderstanding, or disagreement is a mistake. Partners, whether they are marriage partners or business Dyad partners, cannot lead together without honestly addressing what they perceive to be blocking their mutual success. This includes open dialogue in areas where their thoughts are divergent. Healthy Dyad Partnerships require the ability of the partners to recognize and work through areas of conflict.

Conflict is not considered to be particularly desirable among people. The word may even conjure a vision of violence. (After all, we sometimes euphemistically label military actions that cost soldiers their lives conflicts rather than wars.) For many of us, conflict is unpleasant, and uncomfortable. We often choose to avoid it.

Sometimes we may not want to risk facing even the short-term discomfort that open disagreement brings. We might fear that arguing with our partner could cause long-term harm to our relationship. (This may be true if we have not established bonds that are strong enough to remain intact during less-than-harmonious times or our differences are so great that we cannot compromise or one or both of us lacks the skill or emotional maturity to negotiate constructively) Any of these situations has the potential of being fatal to a Dyad. (Marriages faced with these types of challenges have been known to end in divorce.)

Hopefully, most individuals promoted into management will not be fatally traumatized by the latter two problems. They will have consciously worked to build a mutually respectful bond as partners. That’s important, because conflict should be expected between them. Two leaders have been paired to bring two skill sets together for the creation of a synergy needed in the next era of healthcare. They come from different professional cultures, and maybe other different cultures due to ethnicity, gender, or family background.

While Dyad Partners share interdependent goals, performance criteria and activities, each has his own behavioral preferences for performance of joint activities. In order to bring their model of leadership up to its full potential, they should sometimes disagree. Working through their differing points of view (also called conflict resolution) is healthy for organizations and groups. It can help both individuals, and the Dyad Partnership, grow stronger. In addition, it helps organizations avoid a phenomenon known as groupthink (Display 3-4).

Display 3-4 Groupthink

Groupthink is “the pressure to achieve a unanimous decision, which overwhelms individual group members’ motivation to weigh alternatives realistically.” As a result, individuals neglect critical thought and the need to weigh pros and cons.

Groupthink occurs when group members want to achieve consensus, maintain good feelings among group members, and appease leaders.

Groupthink occurs most often in crisis, among tight-knit groups and where members are insulated from criticisms of qualified outsiders or when powerful leaders promote his or her favored solution.

Adapted from Newman, D. (2000). Sociology: Exploring the architecture of everyday life. Thousand Oakes, CA: Pine Forge Press.

A Dyad Partnership could fall victim to the same groupthink problems if one or both partners is more concerned about the relationship than to the organization’s success. It can occur if one leader feels “less than” the other in any way. Their entire team could also get stuck in this mode if they observe the leaders struggling with power or with one continually acquiescing to the other without an observable (but civil) weighing of options. If a partner leader continually and aggressively promotes (or demands) his solution as the only solution, the entire group may stop thinking critically.

At a time when healthcare organizations need innovation, successful Dyads understand that failing to acknowledge conflict can have serious ramifications for their success. They understand, too, that confronting conflict is not only desirable, it is indicative of engagement with the organization and Dyad partners.

David Augsburger recognized this when he wrote, Caring Enough to Confront, in 1983. He pointed out that people who choose not to address their conflicts because of discomfort or perceived risk to the relationship are choosing their comfort over the health of the relationship. It is those who truly care about the organization, and in our case, the success of their Dyad partnership, who will choose confrontation over conflict avoidance. Confronting misalignments, disagreements, or divergent goals is honest. Augsburger points out that selective honesty is not honesty at all—and that good relationships require honesty in two way communications. Augsburger doesn’t advocate war-like, no holds barred, winner take all conflict. In fact, he talks about confrontation where, “truth told with love brings healing, enables us to grow and produces change.” His underlying tenet is that “truth and love are the two necessary impediments for any relationship with integrity” (24).

If you’re uncomfortable with the word “love” for your business partner, just substitute “care” or “concern.” The point is that all human interactions are about relationships. All relationships are interpersonal, and that must be considered when working with a partner on how you will manage together. When working on conflict resolution it’s important to remember this. The best Dyad partners, like the best marriage partners are fair, reasonable, kind, compassionate and empathetic, even during conflict.

Dyad partners may face conflicts caused by intellectual differences, beliefs about shared issues, or struggles for power and resources (Display 3-5). Comanagement may be difficult because of differences in managerial style. Perceived or real differences in status of two who are supposed to be equal partners can add to conflict, because “conflict is less and performance is more effective when there is a congruence of status” (25).

Display 3-5 When Dyads Can’t Succeed/Resolve Conflict

We are champions for Dyad leadership because of its benefits …

But, we have a note of caution for executives who implement the model. Not every individual is able to overcome cultural conditioning or personal proclivities. Some may not be able to learn how to work in a partnership. Some will be unable to share power and accountability.

Their styles in managing conflict may never evolve beyond forcing (utilizing position power to bend others to their will).

The thoughtful executive will observe how individual Dyad leaders deal (or refuse to deal) with conflict. This is a strong indicator of whether he or she can succeed in this type of relationship.

As leaders, we sometimes make hiring mistakes but because we care about our organizations, we must correct these. Dyads aren’t for everyone. Leadership positions aren’t for everyone. When a partner doesn’t fit as a Dyad leader, it’s time for a separation—or divorce. (Those who cannot manage together are unlikely to be good leaders even as single leaders in an era where team skills and a need to decrease silo thinking is essential for an organization’s success.)

Role ambiguity, different perspectives, overlapping duties, and dual loyalties (to both a profession and an organization) are all potential areas of conflict that are especially likely in the Dyad Management Model. When healthy Dyad relationships exist (where both leaders are emotionally healthy and share mutual respect and trust) individuals are able to resolve their conflicts through productive problem solving techniques. Having agreed on priorities, expectations, goals, formal operating guidelines (how we will make decisions) and basic methods for work, they can collaborate and redefine their conflicts as problems to solve together.

Dyad leaders who can resolve conflict are skilled in interpersonal negotiations. They listen before they talk and they explore options together. They have patience and integrity. They avoid the presumption of ill intention on the part of their partners. They focus on the issues, breaking big issues into smaller issues and discuss them, while controlling their emotions. They don’t threaten or manipulate. They are invested in reaching understanding, resolving points of differences, and focusing on problems. They also don’t waste time trying to negotiate what can’t be negotiated: Core values, integrity, emotions, attitudes and trust. Instead, they concentrate on things their partners and they can change together: Behavior and organizational decisions.

Healthcare leadership Dyads are established to bring together two managers with different skills and abilities. They are paired because they have different professional backgrounds. They come from different cultures. Conflict is to be expected. In fact, it is desired, because the strength of this leadership model does not stem from how much the two think identically. The theory behind Dyad leadership is that the quality of decision making will be enhanced when two leaders are able to constructively bring their differences to their mutual work. Their success depends on their ability to recognize, acknowledge, discuss and manage their conflict. Each must understand and deploy the art of persuasion. Each must be graced with the ability to compromise and/or change.

Early in their partnership, Dyad leaders will need to determine how they can most effectively communicate on a day-to-day basis. They have different responsibilities, and may go days without face-to-face time. One of the strengths of this model is that two leaders can “cover” more territory and attend different meetings. However, this increases the challenge of keeping each other informed. A plan for a regular information exchange (calls, e-mails, scheduled meetings), along with an agreement of what information each needs or wants to know, is an important part of the individuals’ shared responsibility. This will save the time that would have been used to correct possible misinformation or misunderstandings. Because they are mutually accountable for leading a department, project or operational area, it cannot be assumed that any information that one has isn’t important to the other. Only by talking about what method each prefers for keeping informed, and what information should be shared, can the two leaders really know the best way to communicate with each other.

It is equally important to agree on a methodology for decision making. Strategic decisions (or those that will materially affect the Dyad’s success at meeting their mutual goals) require partners to discuss and decide together. Many of day-to-day decisions fall into the exclusive job description of one partner. Some of these may not be of importance to the other partner (or they may be of importance, but the individual trusts his dyad partner is taking care of these details and does not feel the need to be informed of these). Others might be helpful for him or her to know. It’s a mistake for either partner to assume the other automatically knows which decisions are strategic and need to be made together, which are the purview of only one partner but should be shared with his partner after the decision has been made, and which don’t need to be communicated to the partners at all.

Explicit advice on what teams must agree on is included in a classic book on teambuilding by Dyer, Dyer and Dyer, now in its 5th edition. The authors state that a team must agree on priorities, share expectations, clarify goals, formulate operational guidelines (including how decisions are made), agree on basic work methods, and determined how differences will be resolved (26). This is as true for a Dyad partnership as it is for a larger team.

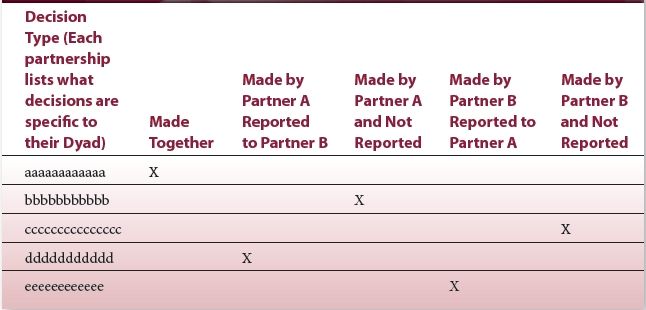

Different Dyads will determine which decisions fall into which category for them and their unique partnership. They may or may not even document their decision making plan on a decision grid (Table 3-2), although most professionals won’t do this, and prefer a verbal discussion only. However they choose to address it, a determination of how decisions will be made, early in the relationship, will increase the speed of their bonding with trust.

Table 3-2 Example of a Dyad Decision-Making Discussion Grid

Trust: The Second Relationship Reinforcer

Trust has been defined as “an assured reliance on the character, ability, strength, or truth of someone” (27). It isn’t automatic just because two leaders have been placed in comanagement jobs, with the same goals and accountabilities. In most Dyad relationships, because of differing cultures, it will take time to establish a level of trust that ensures the individuals success as partners. Each has to demonstrate to the other she is capable and competent to perform her job. In addition, he must earn confidence that he has integrity, communication skills, respect for others, and commitment. This commitment is to the organization and its mission as well as to the success of the Dyad partnership and team.

Writer SM Covey describes trust as “the one thing, if developed and leveraged, has the potential to develop unparalleled success and prosperity” (28). In his book on the subject, he makes the point that what inspires the greatest trust is seeking mutual benefit. For a Dyad, the mutual benefit would be the success of both partners, which leads to success for the organization. In other words, the organization’s goals are best met when individual partners work so that both are successful leaders. Neither has a self-serving agenda in which only one wins as the recognized superior leader. This is difficult if either (or both) originate from what Logan, King, and Fischer-Wright describe as a Tribe in Stage 3—Their research indicated that those who soak long enough in that stage, where “I’m great, you’re not,” and “in order for me to win, you must lose,” become ambassadors for that way of behaving, even when moved to another environment (29). Some leaders from such cultures can become partners, though, especially when they realize that both of them are needed to meet goals that one could not do alone.

To create credibility with each other, and to inspire trust, Dyad leaders must behave in a way that demonstrates a concern for the best interests of their partners, as well as the organization. Besides communication and the skills previously described, there are certain actions that build trust. These include giving credit where credit is due, showing loyalty, and holding yourself and each other accountable.

Giving Credit Where it is Due

In a previous book (30), Kathy described surveys of staff members in which they were asked to describe traits of the best and the worst bosses they had ever reported to. Best bosses were described as giving credit to others for their work. Worst bosses were seen as taking credit for the work and ideas of others.

This shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone who has ever had the misfortune of working for someone (or working with someone) who habitually represents other people’s work ideas as his own. It’s a disheartening, demotivating experience for any employee and one way to ensure a dysfunctional Dyad.

At its worst, credit taking for what someone else did is lying. At its best, it’s an ignorance of what others contribute to your personal success or the group’s success.

If a Dyad partner is guilty of not attributing credit to her partner because of the latter, education and learning about each other’s work should change this behavior. As the partners bond, if one feels she has not been recognized for her contributions, she can discuss this with her partner because of their ability to communicate honestly. If the root problem for not giving credit is deliberate prevarication, the partnership is doomed because integrity can’t be negotiated or learned.

It’s a good practice in any relationship to look for ways to recognize your partner for his contributions. (Of course, this is true for all members of your team.) Everyone appreciates recognition. It strengthens bonds and increases motivation to perform well.

Showing Loyalty

Partnerships require loyalty. While Dyad leaders may not agree, they need to know they are supported in spite of these. In marriages, there are times when a spouse must choose between family and friends and husband or wife. The same will probably be true with Dyad partners from different professional or cultural families. Recognizing relationship imperfections and working on them to improve partnership is not the same thing as complaining about your partner to your professional colleagues.

For example, the administrator Dyad partner may hear culturally based criticism of her physician partner. Another executive might say, “It must be a real problem working with a doctor—the arrogance must get under your skin.” Loyalty to her partner prevents her from either staying silent or agreeing. A loyal partner would counter with statements about why she enjoys working with her partner or how she hasn’t found him to be arrogant at all. This loyalty teaches others they cannot “divide and conquer” a leadership team. It enforces the partnership bond.

Holding Yourself and Each Other Accountable

Dyad leadership is about each partner contributing his unique skills. Shared success is only possible if each knows what her responsibilities are, what her partner’s responsibilities are, and that both will be accountable to complete the tasks assigned to their roles (completely, accurately, and within a defined time span). Written job descriptions are a must and may have to be continually refined for increased clarity around roles and responsibilities.

Mature employees hold themselves accountable for the completion of their specific jobs. They monitor their own quality and self-correct when necessary. Mature managers do the same thing in their roles. Mature Dyad leaders do this, and they hold their partners accountable, too. Trust is built when each individual does what he says he will do and completes his part of the Dyad work.

Accountability is about more than responsibility for individual or joint task completion. It is about an attentiveness to the actions that strengthen the partnership bond. In other words, each individual should consciously consider how his or her behavior adds to the success of the management duo. They should both learn to be comfortable with actions that demonstrate they care about their organization, teams, customers, and Dyad partners enough to confront each other about anything that could interfere with this. Each should hold the other accountable for his or her communications, actions that increase or endanger trust, and respectful interactions, even when disagreeing.

Respect: The Third Relationship Reinforcer

In an on-line article on relationships, author R. Graf asks, “In all honesty, do you want to be around anyone who does not respect you? In other words, thinks that you are meaningless, and not worth the time?” (31) Graf is writing about the necessity of respect for communication in marriage but indicated that respect is a simple basic necessity for all human relationships. Families, friends, and work teams function best when respect is part of the culture.

Many healthcare organizations include respect in their core values. Sometimes they spell out what they mean by the “R” word as it relates to customers (patients), visitors, or work associates (Display 3-6). Often it is assumed that everyone knows what respect means or looks like. It is something that we know when we see it. We perceive attitudes of individuals toward ourselves or others as respectful (or not). Sometimes this needs to be spelled out between partners, whether these are spouses or Dyad leaders.

Display 3-6 Respect

The 1913 Webster’s Dictionary defined respect as “to take notice of, to regard with specific attention, to care for, to heed, to consider worthy of esteem, to regard with honor.”

The 2014 Wikipedia definition of respect is “a positive feeling of esteem or deference for a person or other entity, and also specific actions and conduct representative of that esteem.”

The definitions are 100 years apart. Both refer to feelings but the modern, online version goes further: it adds actions and conduct.

For Dyads, actions and conduct not only signal respect to each other, they model for others and signal to others, that the partners hold each other in high regard, both as individual people and as representatives of different professional cultures.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree