Nurses need to recognize when to delegate.

After completing this chapter, you should be able to:

• Define the operational terms delegation, supervision, and accountability.

• Understand and apply the five rights of delegation in nursing practice.

• Delegate tasks successfully, based on outcomes.

• Apply the “four Cs” of initial direction for a clear understanding of your expectations.

• Provide reciprocal feedback for the effective evaluation of the delegate’s performance.

Expert teamwork can make (or break) patient results and our own job satisfaction. As you review the multitude of health care team members you work with, how do you determine the best use of the resources they have to offer? What is your role as the registered nurse (RN) on the team in terms of making these decisions? Your ability to delegate effectively the tasks that need to be done, based on desired outcomes, will go a long way in determining the success of the efforts of your work. As nursing leads the way to better health care across the continuum, RNs will supervise additional innovative roles of care team members as we strive to provide leadership toward cost-effective quality care for better population health (Future of Nursing™ Campaign for Action, 2015).

What Does Delegation Mean?

State boards of nursing and professional associations, such as the American Nurses Association (ANA) and the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN), have clarified definitions of the terms related to clinical leadership. Clinical delegation has been with us since the dawn of nursing, but teamwork has taken on new meaning, as many types of assistive personnel have been added to our care delivery models (Kalisch & Schoville, 2012). Current evidence points to the conclusion that inappropriate care assignments, delegation, and supervision may be leading to missed care and untoward clinical outcomes (Bittner & Gravlin, 2009; Kalisch et al., 2009; Gravlin & Bittner, 2010; Kalisch et al., 2011; Bittner et al., 2011; Hansten 2014a). Researchers reviewing failures to rescue (FTR), a situation in which patients are deteriorating but the symptoms are not noted before death, indicate that vital signs, neurological status, and urine output changes may occur up to 3 days before the final events. The RN’s choice of nursing assistants, how carefully they are supervised, and how well the RN interprets patient data provided by assistive personnel, may be either life threatening or lifesaving to patients (Bobay et al., 2008). Let us define delegation and accountability to minimize RNs’ confusion about their roles.

As you can see, these are generic definitions, used as standards across the country; most states have incorporated similar definitions into their nurse practice acts. A good deal of decision making is left to you as the RN and is also guided by your state’s nursing practice act. You will be selecting the task and the situation in which to delegate or assign work. You will make a decision to delegate based on your assessment of the desired outcome and the competency of the individual delegate. These clinical decisions require complex critical thinking skills and are certainly more involved than a simple process for time management! In the pages ahead, we discuss steps that use the “five rights” that will assist you in this practice, making it easier for you to maximize safely the work of your team.

Nurses are often confused regarding supervision. This responsibility does not belong to only the one with the title of manager or house supervisor; rather, the expectation by law is that any time you delegate a task to someone else, you will be held accountable for the initial direction you give and the timely follow-up (periodic inspection) to evaluate the performance of the task.

The Delegation Process

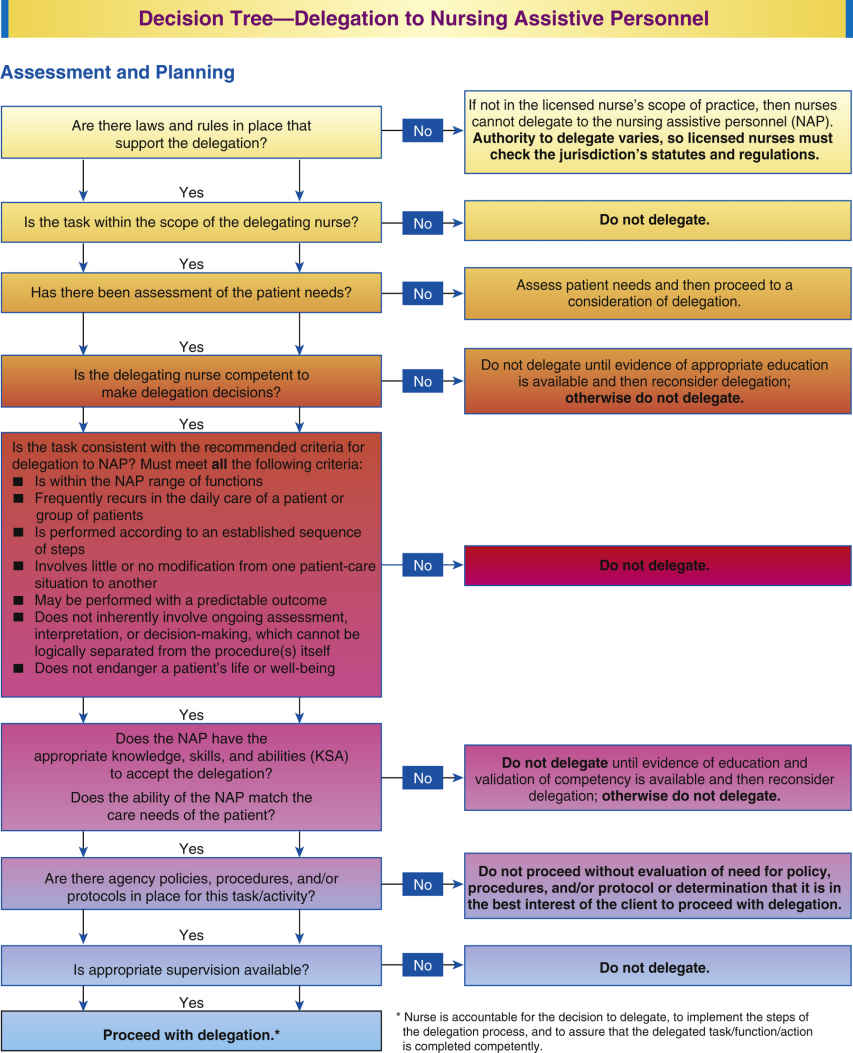

In order to determine when an RN should delegate the ANA, the NCSBN, and your own state’s nursing practice acts offer decision-making support. See Fig. 14.1 for the Decision Tree for Delegation by Registered Nurses to Unlicensed Assistive Personnel (ANA, 2012).

FIG. 14.1 Decision Tree for Delegation by Registered Nurses. American Nurses Association 2012. ANA’s Principles for Delegation by Registered Nurses to Unlicensed Assistive Personnel (UAP). http://www.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/ThePracticeofProfessionalNursing/NursingStandards/ANAPrinciples/PrinciplesofDelegation.pdf, p. 12.

After it is determined the RN is able to delegate through assessment and planning, then the RN must communicate. Initial direction and ongoing discussion must be a two-way process involving the nurse who assesses the nursing assistive personnel’s understanding of the delegated task and the nursing assistive person who asks questions regarding the delegation and seeks clarification of expectations if needed.

Surveillance and supervision are ongoing through the episode of care. The purpose of surveillance and monitoring is related to the nurse’s responsibility for patient care within the context of a patient population. The nurse supervises the delegation by monitoring the performance of the task or function and assures compliance with standards of practice, policies, and procedures. Frequency, level, and nature of monitoring vary with the needs of the patient and the experience of the assistant.

Evaluation and feedback can be the forgotten steps in delegation and should include a determination of whether the delegation was successful and a discussion of parameters to determine the effectiveness of the delegation (ANA & NCSBN, 2006, pp. 7–9).

Who is Accountable Here?

One of the biggest questions concerning teamwork and delegation is the issue of personal accountability. The definition of delegation already notes that the nurse is accountable for the total nursing care of the individuals. What does this really mean?

Some nurses equate accountability with “I am the one to blame.” With that kind of attitude, no wonder there is reluctance to delegate! What is the point of delegating if someone else is going to make a mistake and you are going to take the blame? Let’s not forget that accountability also means taking the credit for the positive results we achieve through the actions and decisions we make, as well as our freedom to act because of our licensure. Our individual choice to take actions (personal accountability) is based on our professional knowledge and judgment, unleashing the art and science of nursing as applied to real-time individual patient and family situations using the gifts and skills of team members each day (Samuel, 2006). An important reminder about accountability before you take the weight of the world on your shoulders is:

It is important to focus on what you are accountable for in this process and to let the delegate also assume his or her own level of accountability. Remember, you are accountable for the following:

▪ Making the decision to delegate in the first place.

▪ Assessing the patient’s needs.

▪ Planning the desired outcome.

▪ Assessing the competency of the delegate.

▪ Giving clear directions and obtaining acceptance from the delegate.

▪ Following up on the completion of the task and providing feedback to the delegate.

What if the delegate makes a mistake in completing the task? For what are you accountable? Let us consider the following example:

Based on a review of the previous guidelines, we can say that you did indeed delegate appropriately. Your communication may or may not have been as complete as it needed to be (more about that later). You are accountable for correcting the clinical effects of this error: Did the patient eat or drink too much, requiring the delay or cancellation of surgery? If so, you will call the operating room and make the appropriate adjustments in this patient’s care based on the decision regarding her surgery time. What about the nursing assistant? You are also accountable for following up with her regarding her performance, providing appropriate feedback so that she understands her level of personal accountability as well. For more on the how-tos, read on as we discuss the Five Rights of Delegation.

The Right Task

The first part of any decision regarding delegation is the determination of what needs to be done and then the assessment of whether this is a task that can be delegated to someone else. However, personal barriers in the nurse can prevent letting go of tasks. Some suffer from “supernurse syndrome” and believe that no task should be delegated, because no one can do it better, faster, or easier than they can (Fig. 14.2). Others labor under the idea that never delegating tasks or data gathering will somehow ensure patient safety and believe their martyrdom (and overtime) is respected by their peers. Others fear offering direction and feedback and want assistive personnel to “just do their jobs” without any input from the RN, without understanding fully the RN’s and team member’s accountability for the tasks being performed. These issues, along with role confusion, may create care omissions (Hansten, 2014a, pp. 70–72). In their alarming report, To Err Is Human, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) provided statistical data on the frequency of medical errors and sentinel events occurring within the health care system. The IOM (2000) reported between 44,000 and 98,000 sentinel events as preventable adverse events. Although some patient safety progress has occurred, subsequent studies have estimated 30% of health care spending was wasted on inefficiencies and suboptimal care quality and that 75,000 deaths could have been avoided (Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, 2013).

In comparison, other nurses may be all too eager to delegate the least desirable tasks to someone else. A word of caution is necessary here: If we focus only on making task lists for people to do, we eliminate the very core of our purpose. Remember, your role as the RN on the team involves the coordination and planning of care, with your primary focus on identifying, with the patient and the physician, the desired outcomes for your patients. Once determined, interventions will be readily apparent, and the decision regarding possible delegation of these tasks must be made.

Reflection: Do I personally tend toward being a “supernurse” or “supermartyr” wanting to do everything myself, because I won’t let go of nursing tasks? Or do I tend to be a “dumper” who would rather let the assistive personnel do all messy or difficult tasks? Or do I tend to be afraid to give direction and correct others for fear of not being “liked”? What kind of feedback could I ask for that would help me monitor my tendencies and improve my leadership?

What Can I Delegate?

Fortunately, there are several reference sources to assist you in making this determination. The first place we recommend looking is in the nurse practice act for your state. Each state board of nursing has a nursing practice act that guides nursing decisions about what to delegate to nursing assistive personnel. Be sure you become familiar with your state’s nursing practice statute, regulations, rules, policies, and advisory opinions.

At this point, the majority of state boards have addressed the issue of delegation or assignment and have developed rules that may offer information regarding who can do what. The scope of practice for each care-provider level usually includes a description of the processes that may be performed at that level. In an attempt to clarify the role of the licensed practical nurse (LPN), the National Council of State Boards of Nursing constructed the Practical Nurse Scope of Practice White Paper (NCSBN, 2005), calling for nursing education programs, regulatory agencies, and practice settings to educate nursing professionals about the differences in LPN and RN roles and to articulate clearly the LPN and RN scope of practice regulations. Traditionally, clinical experiences have provided students an opportunity to observe how registered nurses communicate and delegate tasks to LPNs. However, clinical site availability in settings where LPNs are employed has dramatically decreased, preventing the students from observing the delegation of tasks by the registered nurse to the LPN (Garneau, 2012). Therefore, decreased clinical site experiences, coupled with unfamiliarity regarding the scope of practice regulations for the LPN, have also contributed to ineffective delegation (Mole & McLafferty, 2004; NCSBN, 2006).

A key distinction between RNs and LPNs is related to the first step of the nursing process: assessment. The LPN collects data during the health history and physical examination, whereas the RN conducts a comprehensive physical assessment and develops a plan of care for the patient based on assessment findings. Moreover, the RN initiates and provides patient teaching and discharge planning, as well as evaluates the patient’s response to the plan of care and his or her understanding of the information provided (NCSBN, 2016a). The LPN contributes to the development and/or updates the plan of care and reinforces patient teaching and discharge instructions (NCSBN, 2014). In the midst of health care payment reform and attempts to connect all parts of the care continuum for the provision of better health care for entire populations, state practice rules for care providers may be changing quickly. For example, more states have recently promulgated rules related to certified medication aides in long-term care or community settings. These aides are certified nursing assistants who may, with additional training and certification, administer some routine medications, functioning under the supervision of an RN (or possibly LPN, depending on the state). In addition, community health care lay assistants are often deployed out of medical homes (ambulatory care clinics) or public health departments. These workers, following procedural rules, may function as case finders or perform such tasks as vital signs or home checks in the community. An RN or a physician supervises these community health aides. Medical assistants (MAs) in ambulatory clinics are not always specifically addressed by state practice regulations and have functioned under the direct supervision of physicians in their offices, but presently their roles are being regulated in some states. Creative roles will emerge in the future as states and municipalities attempt to find better, more cost-effective ways to deliver care. RNs should remain tuned in to their state’s health division’s regulatory changes as new roles and responsibilities emerge. Whatever roles appear, RNs remain accountable for the nursing care of their patients, even though those they supervise actually may complete tasks. One of the causes of disciplinary action that is listed in many nurse practice codes under “professional misconduct” is “delegating to an unlicensed person activities that can only be performed by licensed professionals” or “failure to adequately supervise or monitor those to whom care has been delegated” (Brous, 2012, p. 55).

The next place to look is in your organization, obtaining a copy of the job description, nursing responsibilities, and the skills checklist for each care provider. This will give you a very specific list of tasks from which to work, but remember, there are other considerations. Simply because the skills checklist includes ambulation of patients, it may not be advisable to delegate the first ambulation of a postoperative total hip replacement patient to the new patient care assistant (Critical Thinking Box 14.1).

If you have questions and need clarification for your state, go online to your board of nursing to consult statutes, rules, regulations, and advisory opinions or call your nursing regulatory body for assistance. (See www.ncsbn.org for links to your state’s nursing regulatory commission.) Be aware that your state may have introduced or passed a bill that may affect your practice in relation to residents of neighboring states. As of July 2015, 25 states had passed legislation approving interstate compact licensure regulation legislation designed to allow nurses to practice across state lines because of e-consultation, telenursing, or other technology that would broadcast nursing practice across state borders, and 7 more states had pending legislation (NCSBN, 2016b).

Beyond the law, your employer will have job descriptions and skills checklists that may clearly define the role of the caregiver. If you have not seen these documents, be sure to review them soon. This is the baseline for determining “who does what” and selecting the right task to delegate. As many organizations develop creative assistant roles to leverage the professional judgment of registered nursing personnel, the scope of practice of each role is defined first by law. If the organization extends the role of a patient care technician to include preoperative teaching, you want to be aware that this is clearly an RN function and by law is not allowed to be delegated to the technician.

Is There Anything I Cannot Delegate?

Again, your first resource is the law. Many states are very specific in their descriptions of what duty cannot be delegated and belongs only to the RN’s scope of practice. The NCSBN reminds us that:

Nursing is a knowledge-based process discipline and cannot be reduced solely to a list of tasks. The licensed nurse’s specialized education, professional judgment, and discretion are essential for quality nursing care.… While nursing tasks may be delegated, the licensed nurse’s generalist knowledge of client care indicates that the practice-pervasive functions of assessment, evaluation, and nursing judgment must not be delegated (NCSBN, 1995, p. 2).

According to nurse-attorney Joanne P. Sheehan, nurses cannot delegate the following:

Assessments that identify needs and problems and diagnose human responses

Any aspect of planning, including the development of comprehensive approaches to the total care plan

Any provision of health counseling, teaching, or referrals to other health care providers

Therapeutic nursing techniques and comprehensive care planning (Sheehan, 2001, p. 22) (Critical Thinking Box 14.2).

With the right task selected according to state scope of practice, the policies in your agency, and your assessment of the situation, there is still work to be done.

The Right Circumstances

Next, “Right Circumstances—appropriate patient setting, available resources, and consideration of other relevant factors” (NCSBN, 1995, p. 2) suggests that the staffing mix, community needs, teaching obligations, and the type of patient receiving care should also be considered. Different rules for delegation may apply regarding what and how an RN must delegate in-home care, long-term care, or care in community homes for the developmentally disabled or group boarding homes for assisted living (Hansten et al., 1999; Hansten & Jackson, 2009).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree