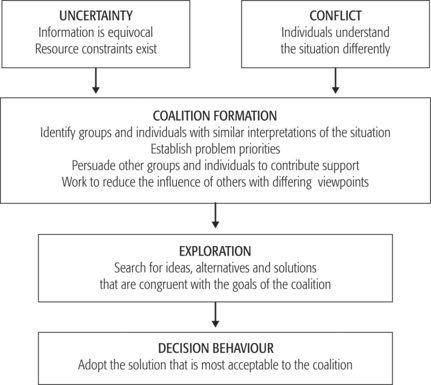

CHAPTER 9 Decision-making and the health service manager Decision-making is seen as a fundamental element of organisational processes, core to managerial work and facilitating the smooth running of complex organisations such as those involved in the delivery of health care services. Managers spend much of their time making decisions at both a strategic and operational level (Mintzberg 1973, Stewart 1976). Decision-making theories scarcely question the status of the manager as a decision maker, to the extent that ‘managing’ and ‘decision-making’ are practically synonymous. Following an extensive literature review, Eisenhardt and Zabracki (1992) concluded that organisational decision-making has essentially developed along three dominant paradigms: rationality, politics and ‘garbage can’. Rationality represents behaviour that can be broadly described as calculated, sensible, logical or instrumental (Dean & Sharfman 1993). Rational theories assume that action depends on anticipation of the future effects of current actions and that alternatives are interpreted in terms of their expected consequences. Consequences of decisions are evaluated in terms of the extent to which they are thought to serve the preferences of the decision maker. Decision-making is seen as a step-by-step process that is both logical and linear: an approach considered to be rational. One major assumption is that the rational approach provides ‘one best way’ to reach decisions and views the decision-making process as a sequential series of activities, leading from the initial identification of the need to make a decision, through evaluation of alternative courses of action and the selection of the preferred alternative, to the implementation of the action. The aim is to make an optimal decision based on a careful evaluation of alternative courses of action. As March (1994) points out, studies of decision-making in the real world suggest that this is a fallacy, in that not all alternatives are known, not all consequences are considered and not all preferences are attended to at the same time. Instead of considering all alternatives, decision makers appear to consider only a few and to look at them sequentially rather than simultaneously. Decision makers do not consider all consequences, focusing on some and ignoring others. Although decision makers may try to be rational, they are constrained by their ability to process all the required data and by incomplete information. Simon (1945) was one of the earliest authors to argue the limitations of the rational model of decision-making. Simon contended that decision makers were constrained by the complexity of modern organisations and by their own limited cognitive capacities. Decision makers were unable to operate under conditions of perfect rationality. The issue for decision makers is likely to be ambiguous or open to varying interpretation, information about alternatives may not be available, criteria by which potential decision outcomes are to be evaluated may be unclear or not agreed. Furthermore, the time and energy available to decision makers is limited by circumstance, making the search for better choices impractical. Managers, in the real world, operate in an environment of bounded or limited rationality. They intend to be rational, and indeed their behaviour is reasoned — it is not irrational; but it is unrealistic to expect adherence to the rigorous requirements of totally rational behaviour. The limitations of human cognitive abilities and the complex demands of the organisation and its operating environments limit the degree of rationality that is possible (Miller et al 1996). Managers are therefore seen as making ‘satisficing’ decisions rather than ‘optimising’ decisions. Satisficing involves choosing an alternative that exceeds some criterion or target and requires only a comparison of alternatives with that target until one that is good enough is found. It is a ‘best in the circumstances’ decision. Simon (1960, p 20), in later work, described how different types of decisions could be made in different ways. Decisions that occur most frequently may be made in a relatively straightforward way, usually using tried and tested protocols and procedures. These are labelled ‘programmed decisions’. Anybody working in a health service organisation will be familiar with the volumes of policy and procedure manuals that frame not only management decisions at an operational level but also a large part of clinical practice. Research has found that managers are more likely to use programmed decision criteria for important decisions involving larger resource commitment (Sutcliffe & McNamara 2001). The decision largely rests on which policy or procedure to employ. ‘Non-programmed’ decisions, on the other hand, are those for which there is no precedence, are atypical or at least not routine. Generally, ‘non-programmed’ decisions are associated with top management and strategic decisions, assuming managers at an operational level operate in a much more stable and predictable environment. However, there is doubt about whether or not this could be said about the environment of such managers in health service organisations, most especially in large public hospitals. The topic for the decision may be complex, making the definition complicated; information may be needed which is difficult to collect, unreliable, ambiguous and conflicting. There may be pressure for an immediate decision. The situation simply does not lend itself to the orderly application of a rational decision-making model. The issue of rationality in organisational decision-making continues to be a vexed one. The rational view of the organisation as a well-integrated team striving to achieve common goals seems overly optimistic. The complex nature of health care and of service organisations places constraints on management decision-making. Eisenhardt and Zabracki (1992) summed up the opinion of many when they suggested that it was time to drop the rational approach to decision-making and turn to more realistic approaches. One of these is to view decision-making as a political process. Cyert and March (1963) were probably the first to take this approach when they argued that organisations should be seen as consisting of shifting coalitions that form and re-form around issues that concern them. These coalitions are difficult to define and identify, as they will change according to vested interests. Different groups, both internal and external to the organisation, have different goals and strategies for pursuing these goals and are best thought of as stakeholders. Stakeholders are those individuals and groups who rely on the organisation for the achievement of their goals but on whom in turn the organisation relies for their support or cooperation. In the changing environment of the health care organisation, a long list of potential stakeholders may be identified. Blair and Whitehead (1988) used the analogy of too many contenders on the seesaw to describe what can happen when organisations like hospitals have many competing interest groups vying for attention. Health service managers have to deal with not only external stakeholders such as government bodies, patients and consumer groups, insurance companies and other funding bodies, not to mention the media, but also internal groups such as professional employee groups, other staff members represented by unions, as well as board members. A number of professional groups, such as visiting medical officers, span the internal and external divide. It is important to note, however, that organisations do not choose their stakeholders: rather, stakeholders choose themselves. As Daake and Anthony (2000) point out, managers involved in decision-making cannot pay attention to every group equally; they must act within a bounded rationality framework. So managers tend to consciously or subconsciously make judgments on the relative importance of the different stakeholder groups. In this way, decision-making becomes a political process. The search is not only for problem-solving information but also for acceptability limits of stakeholders. Miller et al (1996) described the way in which stakeholders may influence decisions. For example, they may choose to behave in ways that further their own or others’ interests. In doing so, they may define the issue for decision in a way that supports their own ends or alternatively suppresses the opinions of others. They may actively promote their preferred alternatives, which may or may not lead to a decision that will be congruent with the articulated goals of the organisation. In doing so, they use information as a tool, withholding some, ignoring some, while presenting other information that supports their case. They negotiate for support, forming coalitions with other supporting groups, while working to reduce the influence of ‘the opposition’. A number of stakeholder groups may be engaging in similar behaviour. Thus the process may be characterised by various forms of bargaining, negotiating and compromise that may lead to outcomes that are less than optimal for all parties but generally considered to be satisfactory. Most writers agree that the use of power and politics in organisations occurs most frequently in situations when goals are in conflict, where power is diffused through the organisation, where information is ambiguous, where cause and effect relationships between actions and outcomes are unknown or uncertain, and when resources are critical and scarce (Alexander & Morlock 2000). The activities of coalitions during decision-making are summarised in Figure 9.1. The political view of decision-making sees the organisation and the processes within it in quite different terms from the rational model. From the political view, particular decisions will attract stakeholders who see an opportunity to influence the decision outcome in their favour. The decision process therefore shapes who will be involved and those involved shape the decision process. Rationality gives way to political influence and vested interests. Not all decisions are made in the context of political struggle. Some decisions are avoided or passed from one decision maker to another. To explain why this may happen, another body of thought offers a different view from those proposed by the rational model and the political view. This is the appealingly named ‘garbage can model’ of decision-making. The garbage can model (Cohen et al 1972) provides a particularly stark contrast to the arguments of the rational model. It evolved largely because of the rational model’s failure to explain how decisions are made in organisations. It assumes participants have differing levels of influence in the decision-making process. According to the garbage can model, the main components of decisions are problems, solutions, participants and choice opportunities. The latter are ‘occasions in which an organisation is expected to make a decision. While some opportunities, such as hiring and promoting employees, occur regularly, others do not because they result from some type of crisis or unique situation’ (Kneitner & Kinicki 1998, p 361). These components pour into the organisational ‘garbage can’ in a continual stream and in a seemingly haphazard way. Every now and then clusters of these components coincide and a decision is produced. Decision processes are seen as unsystematic and lacking in order, with no consistent control that frames decision processes. To illustrate, Cohen et al (1972, p 2) saw the organisation as a: The three major decision strategies in a garbage can view of the organisation are those of oversight, problem resolution and flight. Oversight is when a choice opportunity, for example a regularly scheduled department meeting, arrives, but no problems present themselves. All the problems in the organisation may not be recognised or are on the agendas of other meetings. The tasks of the meeting are carried out, choices are made with minimum time and energy, but no organisational problems are solved because they are not addressed. Alternatively, there are problems on the agenda which are therefore associated with the particular choice opportunity. The decision makers attached to the choice bring enough energy, knowledge and enthusiasm to meet the demands of those problems. The choices are made and the problems are resolved. Finally, the situation may arise where a number of problems may have been attached to a choice opportunity for some time; for example, problems that remain on the agenda from one scheduled meeting to the next. These problems exceed the energy of the decision makers attached to the choice. In this case a choice is not made, problems are not solved and the problems finally attach themselves to another choice opportunity when it becomes available. In other words, the choice is taken to another arena for decision. Although the problems may be gone from the first arena, no problems have been resolved. As Weick (1979) hastens to point out, this is not meant to be a cynical commentary on organisations. Decisions do get made. Although the picture is one of seeming chaos (and probably feels like it to those involved), the process is not truly random and there are some patterns within the confusion. The garbage can approach to decision-making is congruent with the more recent attention that is being given to chaos theory as an explanation of organisational processes. Chaos theory argues that relationships in complex systems, such as social organisations, are non-linear, made up of interconnections and branching choices that produce unintended consequences (Tentenbaum 1998). A fundamental insight from chaos theory is that the unfolding of the world over time is unknowable (McDaniel 1997). Associated with the chaos view is the notion that organisations have the capacity to self-organise into adaptive patterns and structures without any externally imposed plan or direction. (For further discussion on this issue, see Wheatley 1994.) When individuals are confronted with events, they struggle to make sense of them. Assigning meaning or sense to the situations allows the individual to act. Thus sense-making, literally the process of making sense of a situation, is the primary generator of individual action and hence decision-making (Deazin et al 1999). The meanings that individuals hold have been labelled schemas. Schemas, therefore, are derived from one’s experiences about how the world operates. They are dynamic cognitive knowledge structures regarding specific concepts, entities and events, and are used by individuals to encode and represent incoming information. Schemas serve as mental maps that guide the search for and acquisition of information, and guide subsequent behaviour in response to that information. The function of schemas in decision-making is to provide templates for problem-solving by providing a structure against which experience is mapped and facilitates anticipations of the future. Schemas are expanded and elaborated as they incorporate new information. Over time, as more stimulus information is encountered, the schema for that stimulus becomes more complex, abstract and organised (Fiske & Taylor 1991). The development of expertise results in the development of highly elaborate schemas drawn from the information of many experiences. When the information or experience conflicts with the knowledge of an individual’s schemas, this new information is either ignored as an aberration or cognitively recast to fit current schemas. Alternatively, the individual may modify his/her schema. However, as Harris (1994) pointed out, it is important to recognise that the schema-directed nature of the perceptual process lessens the frequency with which schema-inconsistent information is discovered. The very nature of schemas acts to ensure that drastic challenge to their validity seldom arises (Harris 1994, p 311). As schemas direct searches for information, it is likely that the information uncovered will reinforce these schemas. Fiske (1993, p 182) argued that most people construct meaning of their social environment well enough to enable effective actions: that their ‘thinking’ is good enough to serve their ‘doing’. An individual’s use of expectancies and data suits their purposes, given that they are also alert for incongruent and negative information. Accuracy is not absolute and accuracy demands will be dependent on the purpose. Expectancy of outcomes (the self-fulfilling prophecy) and consensus are often used as a proxy for accuracy (Fiske & Taylor 1991). Further threats to the accuracy of schemas are proposed by Hill and Levenhagen (1995). Schemas are not stable over time, and what fits today may not do so tomorrow. The cognitive ‘short cuts’ that schemas often use (for instance, the use of metaphors and stereotypes), which makes them useful in practice, also limits their accuracy and precision. To add additional detail, however, may render the schemas of less value in articulating ambiguous situations. The incomplete nature of schemas may therefore be both a strength and a weakness. Expertise in establishing and implementing schemas may sometimes be limited by the cognitive ability of the individual. Harris (1994) proposed that schemas guide organisational sense-making on two fundamental levels. First, they facilitate answering the question ‘What or who is it?’ The second question is ‘What should I pay attention to?’ Gioia and Poole (1984) suggested that schema-driven sense-making can occur both consciously and relatively unconsciously. Furthermore, individual schemas can affect manager decision-making in a number of ways. These include the way they frame the question, selection of alternatives, use of information, the confidence they have in a decision and their judgment. Because individuals develop and maintain subjective interpretations of their roles in organisations, different levels of sense-making can be considered important for decision-making. Three levels of sense-making are defined below: personal, interpersonal and inter-group. Inter-group sense-making relates to the interpretive schemas of different communities of specialists who literally think quite differently. This introduces the notion of the collective mind. A collective mind is different from an individual mind because it belongs in the pattern of interrelated activities among a group of people. This notion has been used to describe professional culture in an organisational context (Bloor & Dawson 1994) and contributes an explanation to one of the long-standing problems of management decision-making in health service organisations; namely the conflict between the health service professional and the general manager. Groups such as committees, task forces, working parties and review panels play a key role in organisational decision-making processes. The multidisciplinary team as a decision-making unit has become a feature of modern health service organisations. As an organisational tool, teams can expand the role of the employee beyond the level of performing prescribed tasks to being involved in the larger operations of the organisation. Teams are also thought to prove useful in improving the quality of decision-making, with team interaction building consensus and support for action. It is presumed that having a high level of participation in the decision-making process will result in a decision that everybody accepts. Diverse team membership will promote creativity, with all team members having the opportunity to contribute a different perspective on the problems at hand. Working together, the team will create new solutions. The underlying assumption is that groups of workers and/or managers, often representing multiple points of view, can work together to make decisions that are in the best interests of the health care organisation as a whole. It also assumes that the health care professional, who has traditionally worked independently and autonomously, can function effectively in an interdependent relationship with members of other occupational groups (Alexander et al 1996). The reality, however, is often different. Amason et al (1995) reported that teams are often slow to make decisions and the resulting decisions are not very different from what an individual manager may have reached alone. Decisions over important issues are often viewed with a win–lose mentality, with the decision-making process becoming adversarial rather than cooperative. Judging the importance of a decision may relate more to vested interests than the needs of the organisation. This will often create conflict in the team, making the achievement of consensus on any other decision difficult. Decisions made in teams, therefore, often represent the ‘line of least resistance’, a compromised solution that limits the search for a better solution in order to reduce conflict. The assumption that the decision reached reflects the collective opinion of the team members may also be questioned. Individuals often dominate teams. The reasons for the domination may vary. An individual may dominate because of a personal power base or the power base of the organisational group that the individual represents. An individual may be more passionate or committed to the decision-making process at hand than the rest of the members of the team. Alternatively, the individual may have a loud voice and like talking a lot. The leader of the team has a significant role in ensuring that the voices of all team members are heard and that the final decision is taken in a way that represents the collective view. Many groups falter when it comes to the final decision, and the process by which consensus or at least majority opinion is reached often impairs the decision. Rather than being weakened by internal conflict, some teams fail in their decision-making because of lack of conflict. Conflict is avoided because the team members do not want to air their differences or because they do not want to upset the status quo. Such teams tend not to critically evaluate their own ideas or seek data that will create conflict by challenging their assumptions about the nature of the problems and their proposed solutions. The advantages and disadvantages of group decision-making are summarised in Table 9.1. Table 9.1 Advantages and disadvantages of group decision-making There have also been a number of strategies and techniques developed in an attempt to overcome some of the problems encountered when making decisions in groups. The most appropriate of these tools to use will depend on a number of factors, such as the nature of the group and the decision to be made. For further information, see Chapter 7 and Martin and Tate (1997).

INTRODUCTION

DECISION-MAKING AS RATIONAL CHOICE

THE POLITICAL VIEW OF DECISION-MAKING

THE GARBAGE CAN MODEL

SENSE-MAKING

Schemas

Schema-driven sense-making

Levels of sense-making

Inter-group sense-making

GROUP DECISION-MAKING

ADVANTAGES

DISADVANTAGES

A larger knowledge base. The sum of professional knowledge and organisational experience of a group is greater than that of the individual.

Political activity in the group whereby the vested interests of individuals may influence balanced discussion and alternative actions.

Problems and decision-making opportunities will be understood from different perspectives, widening possible alternative courses of action.

Dominance of the group by people perceived as more powerful, more intelligent, more important or to have the loudest voice.

More people will feel ownership of the final decision reached and have an understanding of the process by which it was achieved.

Different perspectives brought to the group are not tolerated because of preconceived ideas.

The decision will be disseminated more quickly as group members relay information to their particular area of organisational activity.

Social pressures to conform and to avoid conflict discourage group members from contributing to group processes. The social functioning of the group and the need to ‘get along’ becomes the priority rather than trying to make the best decision.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree