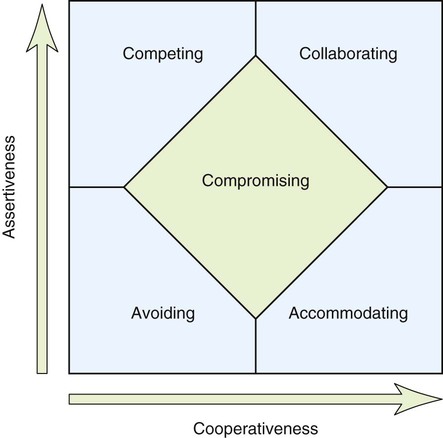

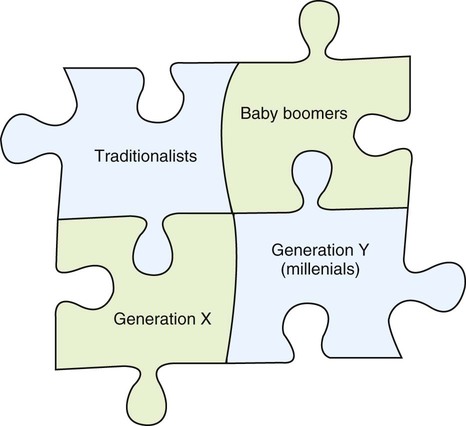

Chapter 5 Even though conflict can be positive, we are conditioned to think it’s going to be a negative experience—something involving winners and losers—so it can be difficult to keep our egos at bay. Instead of seeking solutions, we expect to win or lose, to hurt or be hurt. People tend to resort to one of several conflict management styles according to the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument: avoiding, compromising, collaborating, accommodating, and competing (Figure 5-1). Later in this chapter, we look at smart ways to approach a conflict objectively and constructively. Before we can develop smarter strategies, however, we have to learn to recognize old habits—good or bad. Which of the following is your most common knee-jerk reaction to conflict? So how should we approach conflict when we encounter it? As seen in Chapter 2, four distinct generations now share the workplace for the first time in history, bringing different sets of values, norms, and expectations to the job. In health care, where teamwork is so important, members of different generations might clash from time to time. In fact, a generational tidal wave is hitting the workplace with a force not seen since Baby Boomers arrived at their desks in the early 1970s. Plus, the Millennials, born after 1980, challenge the workplace like never before. Generation Y workers, or Millennials, share many of the same attitudes as their Baby Boomer parents, with whom they typically have close relationships. They are comfortable navigating technology and prefer working in groups. Figure 5-2 shows generations working together to achieve a common goal. These generations are also discussed in Chapter 7. Let’s examine some more specific strategies now. * Change your perspective. In cognitive psychology, this is called “reframing.” What if you no longer cared how a dispute turns out? What if you viewed circumstances from a different perspective? You don’t have to be a prisoner of your own preferences or biases. * Review your personal goals. Goals are aspirations that are truly important. How does the outcome of the conflict fit into your larger goals? This perspective might change the importance you attach to a particular conflict, position, or solution. * Change your response. Visualize what happens if you choose a different response. Listen and then restate your colleague’s or patient’s concern. Ask yourself if you are responsible in a significant way for what has happened. Are your expectations for a resolution unrealistic, out of line, or just not that important? What can you learn from this calm analysis? What solutions might arise from your thoughtful considerations? * Check your impulse control. Ask yourself why some people you know don’t seem to get caught up in certain kinds of conflicts. Ask them for their perspective and advice. * Finally, act like a third party mediator in your own mind. Step outside of yourself for a moment. Ask questions. Why is this issue so important? If you were a disinterested bystander, what could you see that might help resolve a conflict?

Dealing with Others

Consider conflict as a neutral aspect of the workplace, capable of producing innovations or difficulties.

Consider conflict as a neutral aspect of the workplace, capable of producing innovations or difficulties.

Understand the role of ego in conflict and in dealing with difficult people.

Understand the role of ego in conflict and in dealing with difficult people.

Develop a general strategy for dealing with difficult people of all types.

Develop a general strategy for dealing with difficult people of all types.

Explain the current status of racism, prejudice, and bigotry in our society.

Explain the current status of racism, prejudice, and bigotry in our society.

State the importance of multicultural competence to health care.

State the importance of multicultural competence to health care.

Create a thoughtful, consistent, and positive way to answer the phone.

Create a thoughtful, consistent, and positive way to answer the phone.

Learning Objectives for Managing and Resolving Conflict

Name the five conflict management styles.

Name the five conflict management styles.

Explain the four generations of workers as a source of conflict.

Explain the four generations of workers as a source of conflict.

Name other sources of conflict in the workplace.

Name other sources of conflict in the workplace.

Explain how reframing can eliminate conflict.

Explain how reframing can eliminate conflict.

Don’t Take This Personally

Identifying Sources of Conflict at Work

Four Generations at Work

Strategies for Managing Conflict

Reframe to Eliminate Conflicts