D

Dementia

Description

Dementia is a syndrome characterized by dysfunction or loss of memory, orientation, attention, language, judgment, and reasoning. Personality changes and behavioral problems such as agitation, delusions, and hallucinations may occur. Ultimately these problems result in alterations in the individual’s ability to work, fulfill social and family responsibilities, and perform activities of daily living.

Pathophysiology

The two most common causes of dementia are neurodegenerative conditions (e.g., AD) and vascular disorders. Dementia is sometimes caused by treatable conditions that initially may be reversible, such as vitamin B1 and B12 deficiencies, thyroid disorders, subarachnoid hemorrhage, prescribed drugs (e.g., anticholinergics, hypnotics, cocaine), alcoholism, and head injury. However, with prolonged exposure or disease, irreversible changes may occur.

Vascular dementia is loss of cognitive function resulting from ischemic or hemorrhagic brain lesions caused by cardiovascular disease. Vascular dementia may be caused by a single stroke (infarct) or by multiple strokes.

Clinical manifestations

Other clinical manifestations of dementia are discussed with Alzheimer’s disease (p. 23).

Diagnostic studies

Diagnosis of dementia related to vascular causes is based on the presence of cognitive loss, the presence of vascular brain lesions demonstrated by neuroimaging techniques (CT or MRI), and the exclusion of other causes of dementia (e.g., AD).

Nursing and collaborative management

Management of dementia is similar to management of the patient with AD (see Alzheimer’s Disease, p. 27). One form of dementia, vascular dementia, can often be prevented. Preventive measures include treatment of risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, smoking, hypercholesterolemia, and cardiac dysrhythmias. Drugs that are used for patients with AD are also useful in patients with vascular dementia.

Diabetes insipidus

Description

Diabetes insipidus (DI) is caused by a deficiency of production or secretion of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) or a decreased renal response to ADH. The decrease in ADH results in fluid and electrolyte imbalances caused by increased urine output and increased plasma osmolality. Depending on the cause, DI may be transient or a lifelong condition.

There are several types of DI. Central DI (also known as neurogenic DI) results from an interference with ADH synthesis, transport, or release. Causes include brain tumor or surgery, central nervous infections, and head injury. It is the most common form of DI.

Nephrogenic DI occurs when there is adequate ADH, but there is a decreased response to ADH in the kidney. Causes include drug therapy (especially lithium), renal damage, and hereditary renal disease.

Psychogenic DI, a less common condition, is associated with excessive water intake. This can be caused by a structural lesion in the thirst center or a psychologic disorder.

Clinical manifestations

The primary characteristic of DI is excretion of large quantities of urine (2 to 20 L/day) with a very low specific gravity (<1.005) and urine osmolality (<100 mOsm/kg). Serum osmolality is elevated as a result of hypernatremia, which is caused by pure water loss in the kidney.

Diagnostic studies

Nursing and collaborative management

Management of the patient with DI includes early detection, maintenance of adequate hydration, and patient teaching for long-term management. A therapeutic goal is the maintenance of fluid and electrolyte balance.

For central DI, fluid and hormone therapy is necessary. Fluids are replaced orally or IV, depending on the patient’s condition and ability to drink copious amounts of fluids. If IV glucose solutions are used, monitor serum glucose levels because hyperglycemia and glucosuria can lead to osmotic diuresis, which increases the fluid volume deficit.

■ Maintain an accurate record of intake and output and daily weights to determine fluid volume status.

Treatment for nephrogenic DI revolves around dietary measures (low-sodium diet) and thiazide diuretics. Limiting sodium intake to no more than 3 g/day often helps decrease urine output. When a low-sodium diet and thiazide drugs are not effective, indomethacin (Indocin) may be prescribed. Indomethacin, a nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID), helps increase renal responsiveness to ADH.

Diabetes mellitus

Description

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a chronic multisystem disease related to abnormal insulin production, impaired insulin utilization, or both. Currently in the United States an estimated 25.8 million people, or 8.3% of the population, have diabetes mellitus. Approximately 7 million people with diabetes mellitus have not been diagnosed and are unaware that they have the disease.

■ The two most common types of diabetes are classified as type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus (Table 30).

Table 30

Comparison of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

| Factor | Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus | Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus |

| Age at onset | More common in young people but can occur at any age. | Usually age 35 yr or older but can occur at any age.Incidence is increasing in children. |

| Type of onset | Signs and symptoms abrupt, but disease process may be present for several years. | Insidious, may go undiagnosed for years. |

| Prevalence | Accounts for 5%-10% of all types of diabetes. | Accounts for 90%-95% of all types of diabetes. |

| Environmental factors | Virus, toxins. | Obesity, lack of exercise. |

| Primary defect | Absent or minimal insulin production. | Insulin resistance, decreased insulin production over time, and alterations in production of adipokines. |

| Islet cell antibodies | Often present at onset. | Absent. |

| Endogenous insulin | Absent. | Initially increased in response to insulin resistance. Secretion diminishes over time. |

| Nutritional status | Thin, normal, or obese. | Frequently overweight or obese. May be normal. |

| Symptoms | Polydipsia, polyuria, polyphagia, fatigue, weight loss. | Frequently none, fatigue, recurrent infections. May also experience polyuria, polydipsia, and polyphagia. |

| Ketosis | Prone at onset or during insulin deficiency. | Resistant except during infection or stress. |

| Nutritional therapy | Essential. | Essential. |

| Insulin | Required for all. | Required for some. Disease is progressive and insulin treatment may need to be added to treatment regimen. |

| Vascular and neurologic complications | Frequent. | Frequent. |

Type 1 diabetes mellitus

Type 1 diabetes, formerly known as “juvenile onset” or “insulin-dependent” diabetes, accounts for approximately 5% of all people with diabetes. This type generally affects people younger than 40 years of age, and 40% develop it before 20 years of age.

Pathophysiology.

Type 1 diabetes is an immune-mediated disease caused by autoimmune destruction of the pancreatic β cells, the site of insulin production. This eventually results in a total absence of insulin production. Autoantibodies to the islet cells cause a reduction of 80% to 90% of normal function before hyperglycemia and other manifestations occur.

In type 1 diabetes the islet cell autoantibodies responsible for β cell destruction are present for months to years before the onset of symptoms. Manifestations develop when the person’s pancreas can no longer produce sufficient amounts of glucose to maintain normal glucose. Once this occurs, the onset of symptoms is usually rapid.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

Type 2 diabetes mellitus was formerly known as “adult-onset diabetes (AODM)” or “non–insulin-dependent diabetes (NIDDM).” This type is the most prevalent type of diabetes, accounting for greater than 90% of patients with diabetes.

Pathophysiology.

In type 2 diabetes, the pancreas usually continues to produce some endogenous (self-made) insulin. However, the insulin that is produced either is insufficient for the body’s needs or is poorly used by the tissues. The presence of endogenous insulin is the major pathophysiologic distinction between type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

Four major metabolic abnormalities play a role in the development of type 2 diabetes.

Individuals with metabolic syndrome are at an increased risk for the development of type 2 diabetes (see Metabolic Syndrome, p. 415).

Disease onset in type 2 diabetes is usually gradual. The person may go for many years with undetected hyperglycemia that might produce few, if any, symptoms. Many people are diagnosed on routine laboratory testing or when they undergo treatment for other conditions and elevated glucose or glycosylated hemoglobin (A1C) levels are found.

Prediabetes

Individuals diagnosed with prediabetes are at increased risk for the development of type 2 diabetes. It is an intermediate stage between normal glucose homeostasis and diabetes where the blood glucose levels are elevated, but not high enough to meet the diagnostic criteria for diabetes. Prediabetes is defined as impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), impaired fasting glucose (IFG), or both.

People with prediabetes usually do not have symptoms. However, long-term damage to the body, especially the heart and blood vessels, may already be occurring. It is important for you to encourage patients to undergo screening and to provide teaching about managing risk factors for diabetes.

Clinical manifestations

Type 1 diabetes

Because the onset of type 1 DM is rapid, the initial manifestations are usually acute. The osmotic effect of glucose produces polydipsia and polyuria. Polyphagia is a consequence of cellular malnourishment when insulin deficiency prevents use of glucose for energy. Weight loss, weakness, and fatigue may also occur.

Type 2 diabetes

Manifestations of type 2 diabetes are often nonspecific, including fatigue, recurrent infections, prolonged wound healing, and visual changes. Polydipsia, polyuria, and polyphagia may also occur.

Acute complications

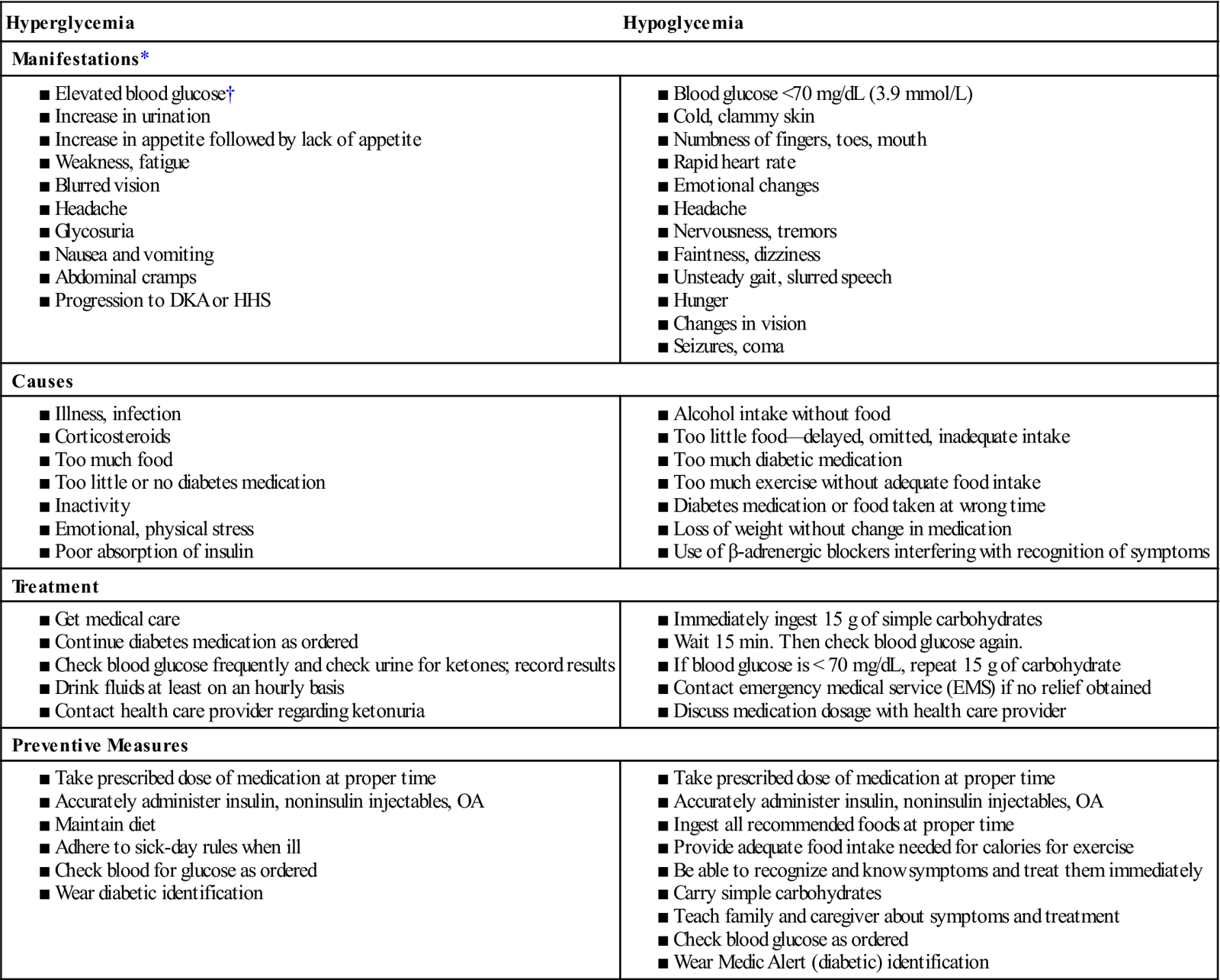

Acute complications arise from events associated with hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia (also referred to as insulin reaction). It is important for the health care provider to distinguish between hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia because hypoglycemia worsens rapidly and constitutes a serious threat if action is not immediately taken. Table 31 compares hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia.

Table 31

Comparison of Hyperglycemia and Hypoglycemia

DKA, Diabetic ketoacidosis; HHS, hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome.OA, Oral agent.

*There is usually a gradual onset of symptoms in hyperglycemia and a rapid onset in hypoglycemia.

†Specific clinical manifestations related to elevated levels of blood glucose vary according to the patient.

Diabetic ketoacidosis

Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is caused by a profound deficiency of insulin and is characterized by hyperglycemia, ketosis, acidosis, and dehydration. Precipitating factors include illness and infection, inadequate insulin dosage, undiagnosed type 1 diabetes, poor self-management, and neglect.

Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome

Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome (HHS) is a life-threatening syndrome that can occur in the patient with DM who is able to produce enough insulin to prevent DKA but not enough to prevent severe hyperglycemia, osmotic diuresis, and extracellular fluid depletion.

Hypoglycemia

Hypoglycemia, or low blood glucose, occurs when there is too much insulin in proportion to available glucose in the blood. This causes the blood glucose level to drop below 70 mg/dL. Manifestations include shakiness, palpitations, nervousness, diaphoresis, anxiety, hunger, and pallor. Untreated hypoglycemia can progress to loss of consciousness, seizures, coma, and death.

Chronic complications

Chronic complications are primarily those of end-organ disease from damage to the blood vessels from chronic hyperglycemia. Angiopathy, or blood vessel disease, is one of the leading causes of diabetes-related deaths. These chronic blood vessel problems are divided into two categories: macrovascular complications and microvascular complications.

Macrovascular complications

These complications are diseases of the large and medium-sized blood vessels that occur with greater frequency and an earlier onset in people with diabetes. Risk factors associated with macrovascular complications, such as obesity, smoking, hypertension, high fat intake, and sedentary lifestyle, can be reduced. Insulin resistance appears to play a role in the development of cardiovascular disease and is implicated in the pathogenesis of essential hypertension and dyslipidemia.

Microvascular complications

These complications result from thickening of the vessel membranes in the capillaries and arterioles in response to chronic hyperglycemia. Although microangiopathy can be found throughout the body, the areas most noticeably affected are the eyes (retinopathy), kidneys (nephropathy), and skin (dermopathy).

Diabetic retinopathy is estimated to be the most common cause of new cases of adult blindness.

Diabetic nephropathy is a microvascular complication associated with damage to the small blood vessels that supply the glomeruli of the kidney. It is the leading cause of end-stage kidney disease in the United States. Tight blood glucose control is critical in the prevention and delay of diabetic nephropathy. Hypertension significantly accelerates the progression of nephropathy. Therefore aggressive BP management is indicated for all patients with diabetes.

Neuropathy

Neuropathy is nerve damage that occurs because of the metabolic alterations associated with diabetes. About 60% to 70% of patients with diabetes have some degree of neuropathy. More than 60% of nontraumatic amputations in the United States occur in people with diabetes. Screening for neuropathy should begin at the time of diagnosis in patients with type 2 diabetes and 5 years after diagnosis in patients with type 1 diabetes.

Two major categories of diabetic neuropathy are sensory neuropathy, which affects the peripheral nervous system and is the more common type of neuropathy, and autonomic neuropathy, which can affect nearly all body systems.

Control of blood glucose is the only treatment for diabetic neuropathy. It is effective in many but not all cases. Drug therapy may be used to treat neuropathic symptoms, particularly pain.

Diagnostic studies

The diagnosis of diabetes can be made through one of the following four methods. In the absence of unequivocal hyperglycemia, criteria 1 to 3 should be confirmed by repeat testing.

1. Glycosylated hemoglobin (A1C) of 6.5% or greater.

Collaborative care

The goals of diabetes management are to reduce symptoms, promote well-being, prevent acute complications of hyperglycemia, and prevent or delay the onset and progression of long-term complications. Nutritional therapy, drug therapy, exercise, and self-monitoring of blood glucose are the tools used in the management of diabetes. The major types of glucose-lowering agents (GLAs) used in the treatment of diabetes are insulin and oral and noninsulin injectable agents. For the majority of people, drug therapy is necessary.

Drug therapy: Insulin

Exogenous (injected) insulin is needed when a patient has inadequate insulin to meet specific metabolic needs. People with type 1 diabetes require exogenous insulin to survive. People with type 2 diabetes, who are usually controlled with diet, exercise, and/or OAs, may require exogenous insulin during periods of severe stress, such as illness or surgery. When patients with type 2 diabetes cannot maintain satisfactory blood glucose levels, exogenous insulin is added to the management plan.

Human insulin is prepared using genetic engineering. The insulin is derived from common bacteria (e.g., Escherichia coli) or yeast cells using recombinant DNA technology. Insulins differ by their onset, peak action, and duration and are categorized as rapid-acting, short-acting, intermediate-acting, and long-acting insulin (Table 32).

Table 32

| Classification | Examples | Clarity of Solution |

| Rapid-acting insulin | lispro (Humalog) | Clear |

| aspart (NovoLog) | ||

| glulisine (Apidra) | ||

| Short-acting insulin | regular (Humulin R, Novolin R) | Clear |

| Intermediate-acting insulin | NPH (Humulin N, Novolin N) | Cloudy |

| Long-acting insulin | glargine (Lantus) detemir (Levemir) | Clear |

| Combination therapy (premixed) | NPH/regular 70/30* (Humulin 70/30, Novolin 70/30) NPH/regular 50/50* (Humulin 50/50) lispro protamine/lispro 75/25* (Humalog Mix 75/25) lispro protamine/lispro 50/50* (Humalog Mix 50/50) aspart protamine/aspart 70/30* (NovoLog Mix 70/30) | Cloudy |

*These numbers refer to percentages of each type of insulin.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree