Judith Rosener describes discord caused when the two gender cultures don’t work hard enough to understand each other. She calls it “sexual static,” which causes discomfort for men and frustration for women. Because of this lack of comfort, men “unconsciously exclude women from the executive suite” (27).

Empathy for others who are either uncomfortable with change or actively resisting what they perceive to be a threat to their power (or financial privilege) does not mean accepting that “things could or should stay the way they are.” We are on a fast track to the next era. We know we must transform. We know it takes both male (transactional) and female (transformational) styles of leadership to meet the organizations goals. So, when Dyads are formed to combine two cultures and two sets of skills, it’s essential that we utilize both to the fullest. That requires conscious attention and communication: even if we are uncomfortable with certain topics. Harvard researchers Stone, Patton, and Heen acknowledge that “Gender is a difficult topic for most people to discuss, just as race, politics, and religion may be” (28). Their book title, “Difficult Conversations, How to Discuss What Matters Most,” indicates that it is most difficult to talk about the most important things. For Dyads of opposite genders to fulfill their promise of transformational leadership, they must engage in conversations one or both may be uncomfortable with. Not addressing issues related to gender is to avoid one of the most important topics for bonding. Without partnership bonding, we can’t reach true leadership synergy.

Before the concept of two leaders combining skills as formal Dyads, many “twosomes” have worked together within healthcare to meet organizational goals. Often, they were not positioned as equal leaders within the system. Today, some companies still appear to believe that one “Dyad” leader should report to the other. We have already pointed out why this is not a true co-leadership model. Co-leading does not mean superior–subordinate leadership. This is difficult for some hospital executives to “wrap their heads around” as clinically integrated networks evolve in which medical leaders “co-lead” with administrators. It’s equally difficult when the male-dominated profession of medicine and the female-dominated profession of nursing lead departments or projects together.

Our gender and professional history makes it easy to understand why there are issues with equality in Dyad leadership. So does the fear of loss of power, as well as cultural conditioning that prevents some individuals from asking why we continue to maintain command and control models that have no rational basis?

For example, it is uncommon for individual hospital CNOs to report to hospital CMOs. Yet, it is not uncommon (although becoming less and less so) for system CNOs to report to system CMOs. (This reporting relationship may even be called a “Dyad,” which is a misnomer.) Kathy has previously worked with male CMOs who actively campaigned to have the CNO (key associates), and the entire nursing enterprise report to them. Their rationale? Nurses work or should work for doctors. In addition, non-clinicians within systems have occasionally assumed that the CNO does report to the CMO. Their perception is that this is the “natural order of things” so they innocently believe that one profession, and one gender, automatically works for the other, even when introduced as Dyad partners. This is true even when it is apparent that both are executives who have not care for patients in years.

Root cause analysis (similar to those performed by clinicians when patient care errors occur) explains this phenomenon. Nurses in the majority of hospitals have traditionally reported to CNOs, who traditionally reported to hospital administrators (CEOs, or more recently, COOs), not physicians. However, at the patient care level, nurses (among other responsibilities) performed work prescribed by physicians for the patients. These prescriptions were called “orders.” This word came from the military command-and-control style of leadership. Both the nursing staff and the patients were expected to do whatever the doctor ordered. (To the discomfort of some clinicians, patients are becoming empowered and educated so that they no longer always believe they must do what a physician tells them to do.) Nurses, who are licensed professionals, are governed by their own state boards and are responsible for implementing patient interventions that their medical colleagues have deemed medically essential but only when the nurse judges that the orders are appropriate. They are legally and ethically required to refuse to perform any procedure if they believe it is either beyond their scope of practice or harmful to the patient (or in today’s parlance, the customer, or user of healthcare). Therefore, doctor’s “orders” are really prescriptions, which can be questioned or not fulfilled by either patients or other healthcare team members.

Outside of hospitals, nurses have been employed by physicians within their private offices. But, the vast majority have not been employees of medical doctors. In spite of having worked side by side, there continues to be evidence that the two professions know less about each other than others (or they themselves) assume. Multiple articles and books mention how little the two professions know about each other. Most of these are about physicians not knowing what nurses do, what is involved in nursing care, or understanding the law and regulations that define this field as a separate profession. (Some have even voiced the belief that “nurses work under the physician’s license, which is incorrect, as nurses can only provide care following the regulations provided by nursing licensure”) According to a 2014 New York Times article, an eminent former medical educator, physician, and editor worked with nurses for decades before becoming a hospital patient. It was only at that time that he discovered he “had never before understood how much good nursing care contributes to patient’s safety and comfort” (29).

Nurses have not traditionally reported to physicians. Nursing and medicine are separate professions, with what appears to be little understanding of the female (nursing) profession from the traditionally male-dominated (medical) profession. CNOs and CMOs are executives, not frontline clinicians. There is no rationale for CNOs to automatically report to CMOs. The perception of female nurse executives is that this only occurs because of (i) male executive and male CMO discomfort with a female culture, (ii) unconscious bias, (iii) conscious discrimination, or (iv) outdated command and control leadership models in which executives can’t comprehend or don’t understand the power in new leadership models where synergy of different skills used in partnership can transform organizations.

Leaders who are invested in or comfortable with current professional or gender relationships are able to rationalize not changing even while they preach change for everyone else. It’s helpful to utilize a model called “generative” discussion to talk about why current leadership models exist, why they might not be effective for the next era, and what organizations should consider for their leadership teams of the future. (Display 5-4 explains generative conversations as well as the concept of root cause analysis.)

Display 5-4 Tools for “Understanding”

Root Cause Analysis is a method frequently used by clinicians to discover the initial reason for an error or poor outcome for patients. It can be utilized in any type of problem solving, both within and outside of the healthcare industry. (e.g., a wrong site surgery might be blamed on a nurse not speaking up when she/he believes an error is about to be made. However, the root cause might be an operating room culture where doing so is not acceptable, and thus the nurse fears reprisal from the surgeon.) Bias and stereotyping of others can be among root causes for poor communication in an organization.

There may be more than one root cause for a problem. The process can be used to help organizations transform and learn how to avoid problems before they happen.

Generative Discussions are frequently discussed in relationship to Boards of Directors or Boards of Trustees. However, they are also appropriate to reference as tools for communication for the exploration of factors and information around big issues, problems, or challenges. (There are emotional underpinnings to all of these, especially because solving them must involve change.) Generative conversations come before actions (supported by data). They are group interactions where ideas about a topic are candidly shared. Listening with an open mind is an important part of the experience in which participants share what they believe to be true, their ideas, and experiences. The goal of these planned discussions is to understand perspectives, connect and strengthen relationships.

Dyad leaders of different genders should have their own generative discussions, as part of learning about each other. If one actually does believe the other should report to him/her, it’s important to acknowledge that, and talk it through. Hidden feelings and beliefs will surface in relationships as problems if there is not open discussion.

Discussing the Undiscussables

Ryan and Oestreich have identified subjects that are widely considered as “undiscussables” at work. They’ve also noted that the “undiscussables” are being talked about, but in the wrong places, and not with those who should be discussing them, because their “underground” presence affects the morale and success of organizations (30). In other words, they are openly discussed by groups who feel discriminated against among themselves but not shared with those perceived as instigating the discrimination. Among these are “virtually all types of discrimination” that surfaces in their studies of workplaces. These researchers found that the most difficult thing for people to talk about is the issue of preferences given to one gender over the other within the organization.

We believe it is equally difficult to broach partner problems when they are based on gender, race, ethnic family of origin, or professional tribal bias. However, none of us have been promised an “easy” job when we choose to lead! Just as clinicians are not serving patients to the best of their ability when they don’t consider the reasons for disease and address these, managers who are unwilling to consider reasons for leadership dysfunction (or even notice there are leadership dysfunctions) are not serving their organizations to the best of their ability. Functional, healthy organizations and functional healthy relationships require trust, respect, and communication. True communication between Dyad partners must include the difficult conversations. These lead to trust and respect. Display 5-5 lists reasons conversations can be difficult.

Display 5-5 Why Conversations Can Be Difficult

Every conversation is really three conversations:

1. What really happened?

2. What do we each feel?

3. What do each of us believe is our personal identity?

Most of us believe, deep down, that problems are because of the other person’s selfishness, naiveté, controlling nature, or irrationality.

The other person thinks we are the problem.

We forget to disentangle intent from impact of other people’s actions.

Our assumptions about intentions are often wrong.

Defensiveness is almost always inevitable and most of us assign blame.

We forget that feelings matter in work discussions, or we claim that they don’t.

—Adapted from Stone, D., Patton, B., & Heen, S. (1999). Difficult conversations: How to discuss what matters most. New York, NY: Penguin Books.

Joseph Luft and Harrington Ingham’s model to help people understand themselves and others, referred to as Johari’s window, pointed out that one of our four personality quadrants is what we know about ourselves, but others do not, and another is what others know about us, that we are blind to (31). When partners are able to share some of the former (not everything—we are not asking for complete disclosure. People deserve some discretionary privacy!), they bond better and learn ways to work better together. When the Dyad becomes close enough that both partners feel comfortable to point out areas in the latter, they are not only supporting the organization; they are supporting their partners’ growth. Of course, this requires the maturity of the partner receiving input—defined as an openness to feedback and the potential that she would be a better or more successful leader (or person) if she made changes in behavior. (The other two quadrants of Johari’s Window are what is known to both ourselves and others, and what is unknown by both ourselves and others).

Dyad leaders of different genders have not only an opportunity to enrich the skills and careers of their partners but also an accountability to their teams, customers, and organizations for modeling leadership that will enrich the future of all. This modeling includes visible (i) support for leadership styles of both genders, (ii) willingness to question (and change) behaviors and beliefs based on cultural conditioning, and (iii) willingness to support a partner’s attempts to grow and change. This includes forgiving past actions of the partner or of his or her profession or gender.

Before we address the first and second “modeling,” we need to talk about number 3. Women and minorities have been subjected to discrimination in pay recognition and promotion into top leadership positions. People who deny this, remind us of those who deny that the Holocaust occurred in Germany. History is history. Horrific, horrible things have happened in this world. Prejudice and discrimination are real in society and organizations. Gender and racial bias, as well as social conditioning and culture have brought us to where we are today. However, as we’ve stated, some of these are conscious, and others are not.

When leaders of different genders are willing to grow by confronting their own biases (that includes both genders) and want to change, it cannot be taken for granted that their partners will “forgive and forget” personal past behaviors. Forgiveness is not always immediate, particularly when trust has been lost and needs to be regained. If an individual is additionally painted as “tainted” because of historical relationships between his gender or culture and hers, there is an additional challenge for Dyad leaders on the journey to true partnership!

A good discussion (difficult) between the two, early in the relationship, could be about their perceptions of the other’s gender and culture preferences. This can set a foundation for (even more difficult) conversations about individual (real or perceived) actions, which divide Dyad partners rather than unite them.

Martin Luther King said that, “Forgiveness is not an occasional act. It is a permanent attitude.” Without forgiveness (for real or perceived treatment, prejudice, or day-to-day “slights”), no relationship can thrive. (This is as true for Dyad leaders as it is for a marriage.) In his popular book, with the catchy title, Men Are From Mars, Women Are From Venus, psychologist John Gray make this point: “Gender insight helps us to be more tolerant and forgiving when someone doesn’t respond the way we think he or she should” (32). That’s why Dyad partners of different genders should take some time to gain knowledge about each other.

So what are some of the “insights” that might help Dyad partners understand their coleaders? Here are a few that psychologists, sociologists, and scientist–researchers point out:

- Men mistakenly expect women to think, communicate, and react the way men do. Women mistakenly expect men to feel, communicate, and respond the way women do.

- Men and women often don’t mean the same thing even when they use the same words (32).

- Research suggests that men and women may speak different languages that they assume are the same language. They use similar words to encode disparate experiences of self and relationships. As a result, what is said may be systematically mistranslated. This created misunderstandings that impede communication and limits potential for cooperation in relationships.

- Men have difficulty in hearing what women say. Yet in the different voices of women lies the truth of an ethic of care, the tie between relationship and responsibility, and the origins of aggression because of a failure to connect (33).

- Generally, right-handed men act from either their left (brain) lobe, which is the teaching, verbalization, problem solving, solution giving side, or their right lobe, the artistic, nonverbal side. Rarely can they act from both the right and left lobes at the same time. On the other hand, women are capable of processing data from both the right and left lobes at once. This makes them capable of melding thinking and feeling (34).

- Men and women think differently, approach problems differently, emphasize the importance of things differently, and experience the world around them through different filters.

- Our brains differ in anatomy, chemical composition, blood flow, and metabolism. The systems we use to produce ideas and emotions, to create memories, to conceptualize and internalize our experiences, and to solve problems are different. Women have more connections between the two sides of their brains that may explain how they can process several streams of information at the same time, while men activate only one side of the brain while processing information (35).

- Women have learned that asking to be recognized for their abilities and accomplishments can be a mistake (because they may be “punished” by males in power).

- Men ask for things (like higher pay) two to three times more often as women do. They are expected to self-promote and, as a result, get more recognition and money.

- There are rigid gender-based standards of behavior at work. Women are supposed to be modest, unselfish, and not self-promoting. Their skills and contributions are undervalued so they are passed over for promotions, and they are often left out of the organization’s information sharing grapevine (36).

- In meetings, a woman will come up with an idea, and a man gets credited for it when he mentions it later in the meeting (37).

- Even when women are successful, acceptance among male peers is not easy because men feel a loss of privilege or power (38).

- “For men, conversations are often negotiations in which people try to achieve and maintain the upper hand.” For women, conversations are more often a way to connect or gain confirmation and support (39).

Legato (35), whose information on brain differences is referenced in the points above, has quite a bit more to say about communication between men and women. She shares that there is a body of evidence that men and women hear, listen, understand, and produce speech differently. While women are better at identifying and interpreting nonverbal cues like tone of voice and facial expression, men are sometimes better at identifying straight forward emotions like rage and aggression. Women find verbalization and listening easier. Men are more likely to stick to facts with greater efficiency in the words they use. Women use more facial expressions, tone changes, and physical gestures. Women more often answer questions with a story; men like to draw the shortest line between fact A and conclusion B. They also interrupt a lot—which makes women feel humiliated and disregarded.

Starting the Journey to Better Partnership

Given these observed or researched difference in genders, where should Dyad partners start on their journey to a better partnership? We’ve already suggested a conversation (or multiple conversations) on experiences with perceptions of each other’s cultures (or “tribes”), followed by dialogue (whenever appropriate) about specific perceptions of each other’s actions. These don’t always have to be about attempts to “correct” behavior, inform on blind spots, or ask for change. They should also include praise and appreciation for the partners sensitivity to differences, attempts to change herself for the good of a new next era culture, and personal skills/gifts he brings to the organization and the team. As Dale Carnegie pointed out years ago, “One of the most neglected virtues of our daily existence is the expression of appreciation” (40).

It’s important for Dyad partners to look at their environment with newly sensitized eyes. This may happen initially as they work more closely together with a work partner than they have in the past. One regional system physician CMO who has a longtime reputation for being empathetic, inclusive, team oriented, and open (earned long before he became a Dyad partner) states he was unaware of the bias against having nursing leaders in the organization as part of the top strategic team. “I had always seen the CNO as a powerful person. It never occurred to me that she is not at every decision-making table. After all, she is responsible for the largest workforce in the company. She always gets things done and solves problems without placing blame on anyone. Until I took the job as her Dyad partner, I didn’t realize that she accomplishes so much in spite of being handicapped by being excluded from important discussions. We’re equals in the system, advertise our Dyad partnership, make rounds together on the units, and work together with the medical and nursing staff. Frontline nurses and docs get it—they see us as a pair and are happy about the collaboration we’ve sponsored between our two professions. But the male nonclinician executives? Not so much. I was appalled to discover that I’m invited to strategically important meetings while she’s left off the guest list. The subjects we talk about aren’t any deep dark secrets—and when they are confidential, it’s not like she can’t keep things quiet. She would add a lot to the conversation because, frankly, she knows more about hospital operations than I do. I’ve asked so many why she hasn’t been invited that the other guys are getting annoyed. They just don’t get it. So, my Dyad partner and I talked about it and decided we need to come up with other tactics besides me pushing—because we’re a little fearful they’ll stop inviting me, too … and we desperately need clinical input at the executive strategic level. I keep her informed of course—and we’ll figure out how to get her to the table. But I still can’t get over the resistance to including her—and I don’t think the issue is her personally. It’s their inability to see value in a female nurse voice at the table, even when we’re planning future patient care.”

Before his Dyad experience, this CMO hadn’t been aware of the bias he’s now seeing first hand. That’s not unusual, as gender experts say that men (especially those from predominately white cultures) don’t see what women (and minorities) see. They do not notice the invalidation experienced by women when they make statements in meetings or suggest solutions to problems only to have males repeat what they said later in the meeting, and then be given “credit” for what women brought up first (41). They may not notice that women are interrupted repeatedly by men, and sometimes can’t seem to get a “word in edgewise” while they wait for “their turn” to talk. They might not notice when strategic meetings exclude women—either because they weren’t invited or because the “meeting” occurs at an exclusive men’s club or on the golf course. It may not be clear that two people with virtually identical ways of leading may be labeled hard, feisty, and unpleasant or courageous, no-nonsense and powerful just because of their gender.

Men might (and this isn’t a sure thing) notice hostile sexism, when a woman is treated rudely (either in person or behind her back for “usurping” men’s status and power in their traditional roles). It’s less likely they observe (consciously) benevolent sexism in which women are offered protection and male chivalry for choosing to stay in traditional roles (42). They may be oblivious to the “little things” listed in Table 5-1. As stated in Robinson-Walker’s book (25) men often just don’t see what’s happening to females in the organization around them.

If these realities don’t naturally become clearer as Dyad partners work together, a female partner might become comfortable enough in the partnership to discuss these issues with the male partner. Together, they might brainstorm or strategize how to change the culture, or the male partner might go into a traditional “male hero” model. In that case, he’ll immediately begin by advising (telling) his partner what to do to solve the problem. He might even take action himself, feeling he must solve the problem, and “fix things” for the sake of his Dyad, his team, and his company. He might believe this “action” on his part is the supportive thing to do. As multiple relationship authors (and wives) have pointed out, this isn’t usually what the woman wants! She’s looking for empathy and/or the problem solving that two equal partners could do together. If her male partner takes action on her behalf, she will be perceived as the “weak woman” who is only treated with respect because the strong male insisted on it. (And that isn’t really respect.) She can’t be a leader if her partner must “fight her battles” or solve her problems. In trying to help, he will reinforce stereotypes and disempower her. A much more effective plan to transform the culture begins with generative discussion (between partners) about gender issues. This is in keeping with discussions about any organizational challenge. Partners can then combine their knowledge and thinking to determine strategy and tactics.

One tactic could be an agreement to coach each other on better ways to talk to and understand the opposite gender. Women can learn from men how to best approach other men. Men can learn from women what would make them more effective when working with women. It’s probable that men can teach women strategy and politics and women can teach men more about managing relationships.

Another tactic that works (when partners trust that they are looking out for each other’s best interests) is to agree to observe each other during interactions with others and then offer feedback. When a partner observes behavior or communication that he or she perceives as disempowering or decreasing effectiveness, the each Dyad individual has agreed to share this with each other. This can be followed by peer coaching. In addition, both partners should hone their observation skills about the “little things” like the examples in Table 5-1. Both can point these out to others or request changes in the organization. In fact, it is much more effective for each member of the Dyad to do this. If it appears to always be the female requesting changes to organizational norms or customs, some might perceive this to be her “personal problem,” or “self-esteem issue,” or “push for power,” with a resulting conscious or unconscious disregard or resistance to even small changes. (Some might claim these issues are ridiculously small to bring up—but paradoxically are not willing to change them, which would seem easy to do if they are truly inconsequential.)

Working together on gender issues for the organization has an additional benefit. Discussions about the overall culture have the potential to educate the Dyad leaders on their individual behaviors and opens up opportunities for candid conversation about the Dyad relationship.

Other Cultural Differences for Dyad Partnerships to Consider

A few years ago, Kathy took part in a discussion about diversity in healthcare leadership. The all-white, mostly male group of CEOs and COOs, were bemoaning the fact that they simply could not find minority candidates for executive positions. One, however, was very proud to announce that he was mentoring young black men who had recently graduated with MHAs. During a break, the CNO approached him. “That’s great,” she said, “So we’ll soon be seeing diverse leaders from your organization at these meetings.” Startled, he replied, “Oh, no, it will be at least 10 years before they’ll even be ready for an administrative position.”

Kathy knew that the CEO had an undergraduate degree in sociology and an MHA. She also knew that, after completing a 1-year administrative residency, he “started at the top” as a hospital COO (age 24) and was a CEO by 30. His COO, another white male, also boasted about his “first job” as an assistant administrator.

Her conclusion was (right or wrong): For this individual, an unconscious prejudice, means that minority leaders need more experience than do white males to prove themselves “worthy” of executive positions. She also perceived that, while proud to be mentoring black males, he seemed unaware of his blindness to this personal bias.

Professional backgrounds and gender aren’t the only cultural differences that individuals in Dyads may need to consider and discuss in their journey to a trusted and trusting partnership. If there is a difference in racial and ethnic backgrounds between the two, it is conceivable there will be issues for the partners to talk about and resolve that would not be present if both were of the same cultural and ethnic background. It’s also possible that peer coaching and specific support may be needed by one or both Dyad members.

Research on different leadership styles indicates that racial differences in management are not as prevalent as gender or professional cultural differences. A 1981 study found no significant differences in attitudes toward employees or preferred leadership styles among managers of different races (43). A 1998 study on job applicant’s integrity, showed that race and ethnicity made little difference in scores, but women of all races scored higher that did men (12). Other studies have agreed that there are no significant differences between white and black leaders in values, motivation, or other personal attributes (44, 45). In spite of studies like these, minority leaders, like women, still experience interpersonal issues based on stereotypes and bias, both their own and others. These leaders (and those they lead) do not come from common cultures, either (even when different groups share in the diverse population known as “people of color”) (46). In other words, individuals and individual cultures differ in both their socialization and experiences.

Because influence and comfort with coworkers is greatest among those who are “just like us,” the increasing diversity among leaders and work teams means we should not ignore differences. We need to establish a comfort level with each other so that trust and mutual respect can thrive. A 1991 study by Cox and Blake showed that “well-managed teams with diversity in members can achieve greater performance and cohesion” (47). The same is true of Dyad partnerships. When Dyad partners come from different ethnic or racial cultures, and they can manage well together, they will help all members on diverse teams maximize the team’s effectiveness. (This is discussed further in Chapter 9.) Addressing differences as partners is the first step in strengthening the partnership. For many people, this is one more of those “undiscussables.” However, when differences remain undiscussed, intergroup bias can create discomfort due to “awkward social interactions, embarrassing slips of the tongue, assumptions, and stereotypical judgments.” Sometimes, liking and respect are missing just because unintended slights or undefined bias decreases trust between the leaders.

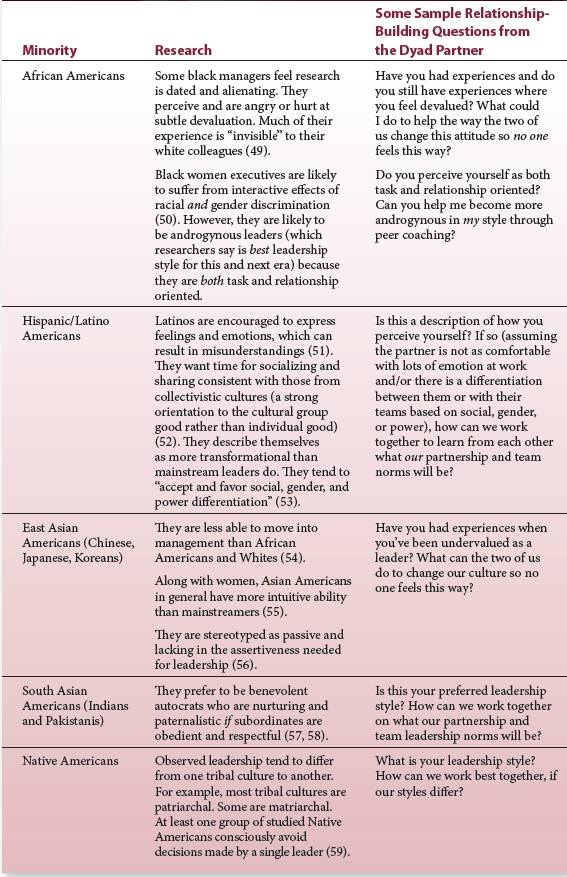

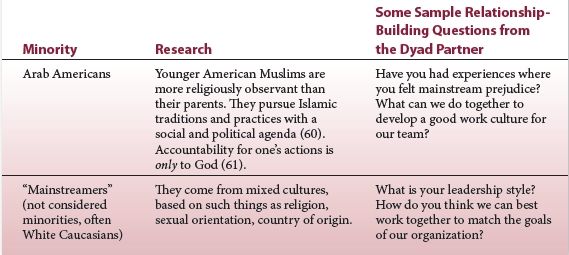

Trust develops over time (48). It’s based on perceived authenticity of others. An authentic Dyad partner doesn’t have to be “just like me,” but he does have to be willing to learn about me, admit she may not understand my background, challenges I’ve faced, my realities as a person and leader, or how I view the world. Building trust with a partner starts with a willingness to have conversations about how the two individuals might differ. A truthful conversation involves both individuals’ willingness to share their beliefs about the other’s culture, a nonjudgmental “ear” when listening to these (however inaccurate) perceptions, and a willingness of both to teach and learn from the other. Then, when trust in each person’s authenticity is established, the two leaders can lead diverse groups together, comfortable in the knowledge that one will help the other avoid (as much as possible) those “awkward social moments” and slips of the tongue with multicultural team members. Table 5-2 lists some research findings on different minority races or groups and questions that would be “discussable.” These could be a starting point for a conversation between Dyad leaders who are ready to get to know each other and understand each other—as long as it is remembered that people (including your partner) are individuals, so studies pointing to an entire group’s experience or behaviors might not be reality for your Dyad partner.

Table 5-2 Leadership and Workforce Research on Diversity and Culture

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree