Chapter 11. Cultural inclusiveness

safe cultures, healthy Indigenous people

Introduction

The most compelling mark of an inclusive society is the respect conferred on its Indigenous people.

Indigenous people in Australia and New Zealand have different histories and experiences. As population groups, what they have in common is a history of colonisation and dispossession that has not yet been fully redressed by non-Indigenous people in either country. New Zealand has made greater progress than Australia in valuing its Indigenous people, particularly since the Treaty of Waitangi, and its mandate for recognition of all New Zealanders as equal before the law. Although Australia has yet to develop a treaty with Indigenous people, there is a renewal of political attention to the need for reconciliation between Australia’s Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. This was enshrined in the national public apology to Indigenous people by Australia’s Prime Minister in 2008, and Indigenous people are awaiting further action at the community level. Much remains to be done in reshaping Australia as an inclusive society. State, territory and Commonwealth government initiatives to ‘control’ Indigenous affairs, and therefore Indigenous people’s health, have polarised public opinion. Some condone heavy-handed measures to intervene in the way some Indigenous communities live their lives, while others are outraged that non-Indigenous norms and expectations would be placed on Indigenous communities. Australian public opinion is also divided on another issue related to inclusiveness. This issue concerns the plight of refugees from other countries, with some citizens advocating a greater human rights orientation, and others arguing for ‘fairness’ in the way migrants are processed and/or allowed into the country. As we have mentioned previously, this is one area where New Zealand political will is decidedly clear, supporting a compassionate basis for decision-making.

The relevance of political decisions governing migrants and Indigenous people is of major importance to nurses and midwives working towards community health and wellness. As a basis for any type of intervention, the professions need to be fully informed of how both historical factors and current realities interact to keep some cultural groups, especially Indigenous people, socially disadvantaged, and relegated to disproportionately high levels of disability and disease. Our evolving research agenda has made some progress in helping inform culturally appropriate actions, particularly in providing insights from the perspective of Indigenous people themselves. Understanding Indigenous ways of knowing, and the worldviews of other cultures should lead to change, but it does not always achieve this. The challenge is to advance this knowledge as a basis for informing community awareness, then providing a rationale for policy and practice with the ultimate goal of social justice. Questions for members of our professions revolve around how we can enact our role as advocates to support political enthusiasm for change, and how we can use Indigenous knowledge and skills to inform the direction of change. These questions lie at the basis of sustaining health improvements for all people so that they become entrenched in good and best practice.

We are both members of the non-Indigenous cultures of our respective countries, and we write this chapter drawing on a wide range of Indigenous and non-Indigenous literature, in consultation with members of Indigenous cultures, and on our respective experiences of the health and political environments in which we live and work. We begin this chapter by delving into some of the successes and failures in Indigenous health in Australia and New Zealand. This is explained within a framework that addresses the influences of the historical, social, economic and situational factors that have prevented Indigenous people from achieving good health. From this base of knowledge, we can work together, seeking common solutions that redress past and current barriers to health and wellness. Then we can work towards helping Indigenous people negotiate retention of their culture, and promote equitable, inclusive environments for health and wellbeing.

Culture and health

Cultural groups are bound together by a tapestry of historically inherited ideas, beliefs, values, knowledge and traditions, art, customs, habits, language, roles, rules, and shared meanings about the world. Culture is therefore multidimensional. Cultural influences are often tacit in people’s behaviours, as unconscious, shared predispositions, rather than deliberate attempts to be distinctive. Despite the commonalities that bind members of a cultural group, behaviours, cultural traits and predispositions are not always expressed in the same way by all who claim membership in the group. Individual expressions of attitudes, beliefs and behaviours vary according to age, gender, personal histories, and situational factors, and these are, in turn, influenced by family, group and community influences.

Diversity in expressions of culture is also a product of how people relate to their environments. Culture is integral to a person’s social life, part of his or her ecological relationship with the world. Cultures are also adaptive, and, in ecological terms, as people in any cultural group interact with their environments, there is a reciprocal effect on the environments and the people themselves (Eckermann et al 2006). The way people respond to, initiate and adapt to changes is therefore a dynamic process, a reflection of the natural,

Objectives

By the end of this chapter you will be able to:

1 explain the influence of culture on health and social justice

2 discuss Indigenous health within the context of primary health care

3 identify risk factors for Indigenous health at the family, neighbourhood and community level

4 explain the importance of historical and cultural knowledge in promoting the health of Indigenous people

5 describe strategies for promoting health literacy in an Indigenous community

6 devise a comprehensive strategy for working with Indigenous families to improve individual, family and community health

7 define cultural safety as a concept and explain its relevance and importance in the provision of health care.

Although there are many commonalities that bind members of a particular cultural group, individual expressions of culture will vary according to the personal characteristics and experiences of the individual.

Cultural behaviours include the way people use language, how they feel and how they learn, what motivates them, how and with whom they interact and express themselves and make decisions (Eckermann et al 2006). Although cultural traditions can bind people together, it is inappropriate to consider members of one or another culture as homogenous, as within cultural groups there is often wide variability.

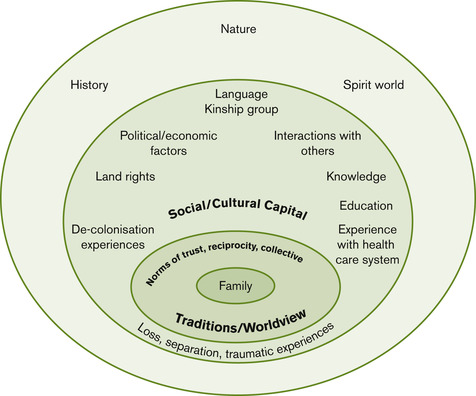

A critical view of culture seeks to overcome the monolithic view that all members are relatively similar. Instead, understanding individuals comes from exploring their history, behaviour, and particular view of the world as it is embedded in their culture, but distinctive in their patterns of attitude and behaviour. Conducting nursing assessments of a person’s needs therefore has to include both unique and common strengths and needs. Indigenous ‘culture’ is not something that can be made explicit, as a formula from which to develop culturally appropriate guidelines and culturally competent care (McMurray & Param 2008). To be authentically inclusive, health professionals have to understand the history and structural factors that have been part of a person’s experience, in the context of diversity within, and external to, the group (Culley 2006). This non-stereotypical approach provides insight into people’s worldview and their history, and the barriers and strengths that can lead to empowerment and self-determined decision-making. Ultimately, this grants the members of a group the freedom to articulate their lives, and their expectations in the voices of their own language and values (Sen 1999). These choices are embedded in family and community and the human right to achieve social and cultural capital (see Figure 11.1).

|

| Figure 11.1 |

Culture conflict

In some cases, the ecological interactions between people, their culture and other cultural groups is mutually beneficial. People of different cultures settling together in a new land often learn from one another, enjoying each other’s foods and ways of cooking, lifestyles and folkways, such as festivals and celebrations. Over time, their long-term contact with one another can result in the type of acculturation where two cultural groups become integrated; or relatively similar (Beiser M, 2005 and National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) 2005). However, attempts at acculturating two groups can also be fraught with conflict. Berry (1995) describes four different reactions to acculturation. The first is assimilation, where one culture abandons their culture in favour of the new or host culture. Integration is the creative blending of the two cultures. Rejection is a reaction in which the new culture replaces the heritage culture, and marginalisation occurs where neither the new nor the old culture is accepted. Clearly, the most desirable option is integration, with marginalisation the least desirable (Beiser 2005).

Culture conflict typically occurs where people are not committed to similar goals or ambitions, and where their decision-making is not based on similar principles and philosophies (Eckermann et al 2006). This occurs often in Indigenous cultures in countries like Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States, where discriminatory and often racist attitudes promulgated by media stereotypes portray Indigenous people as a ‘problem’ rather than showing balanced, positive images of successful Indigenous people and families (Brough M, Bond C, Hunt J, 2004, Ten Fingers K, 2005 and Toussaint S, 2003). Even in the health care system, we tend to purvey the impression that non-white populations need to be reconciled within white, Eurocentric models of care, and their behaviours corrected, to conform with disembodied, purified, scientific solutions (Puzan 2003). This perpetuates unresolved issues that continue to plague the lives of Indigenous peoples, adding cumulatively to their unresolved burden of intergenerational trauma and grief (Menzies 2008).

At the community level, culture conflict erodes social and cultural capital by causing disharmony. When this occurs, members of the conflicting groups close ranks, and withdraw from each other, rather than cooperating to build a system of mutual community support. On the other hand, when people from different cultures live with realistic possibilities for the future, they are more likely to work within a type of cultural relativism; acceptance of one another’s culture as the ‘legitimate adaptation of different peoples to various historical, natural, socio-economic and political environments’ (Eckermann et al 2006:6). Cultural relativism lies at the centre of tolerance and social inclusiveness. For two cultures to work together, no one culture needs to abandon its traditions or philosophies, but each suspends judgement of the other’s beliefs and practices. In this process, each makes a conscious decision to proceed on the basis of their willingness to recognise and respect the beliefs and practices of others, and to continually question their own views and presumptions (Eckermann et al 2006). This is also the first step in maintaining cultural safety.

Cultural safety

Cultural safety is a term that grew out of the colonial history of Aotearoa (New Zealand). It was first described in 1988 by Māori nursing students expressing their concern about safeguarding their culture as they were socialised into the world of nursing education, and ensuring the safety of Māori culture among those they would be helping in practice (Eckermann et al 2006). Their concerns were recorded by Ramsden, a Māori nurse who spearheaded the cultural safety movement in Aotearoa, ensuring that cultural safety found its way into the curricula and nursing practice (Eckermann et al 2006). Cultural safety was never meant to catalogue Māori cultural beliefs, but to recognise power imbalances and inequitable social relationships (Anderson et al 2003). As we mentioned in Chapter 2 cultural safety is a concept that refers to exploring, reflecting on, and understanding one’s own culture and how it relates to other cultures with a view towards promoting partnership, participation and cultural protection. This notion of cultural safety has now evolved beyond working with Māori to include other ethnic and cultural groups (Wilson & Neville 2009). Cultural safety is a form of cultural relativism, which is concerned with how culture shapes power relations within the social world of the community. It is designed to enable safe spaces for the interaction of all cultural groups, and their understanding of cultural identity. It is absent in the face of actions that assault, diminish, demean or disempower the cultural identity and wellbeing of any individual (Nursing Council of New Zealand [NCNZ] 1992).

The first step in achieving cultural safety is cultural awareness. This includes recognising the fact that any health care relationship is unique, power-laden and culturally dyadic. In other words, there is always the potential for one person (the health provider) to hold power over the other person (someone seeking to access services). When the health care relationship is built on a foundation of cultural sensitivity, there is a greater recognition of, and respect for, cultural differences. People develop cultural sensitivity when they begin to engage in self-exploration of their own life experience and realities, and the impact these may have on others. The final stage in developing cultural safety is a conscious commitment to ensuring preservation and protection of others’ cultures. Cultural safety is therefore a type of advocacy informed by a recognition of self, the rights of others and the legitimacy of difference (NCNZ 1996). It is integral to all nursing and midwifery interactions, which means that our practice must be culturally competent . Cultural competence is the process of ensuring that all nursing and midwifery interactions are cultural interactions (Duke et al 2009).

Multiculturalism

Multiculturalism is a value-laden term that has sometimes been used as a panacea for intolerance. The term has been used to camouflage feelings of superiority of one culture over another. It has also been used to salve the consciences of many people, believing that because they live in a community containing many cultures, the community must be inclusive, when this may be disputed by the realities of daily life. In its truest sense, multiculturalism means ‘that people are in fact linked in many more ways than their birthplace divides them’ (Wilding & Tilbury 2004:3). Globalisation has brought multiculturalism under close scrutiny because of the spurious arguments used by the most dominant cultures to maintain their position of power over those who are economically dependent on them for survival. In advancing the global economic development agenda, Indigenous people have often been ruthlessly ignored or dismissed, which is discriminatory and adds to their level of disadvantage. Languages have disappeared and cultural characteristics have gradually withered, as people try to minimise feelings of ‘difference’, and find ways of coping with feeling excluded from mainstream society. These psychosocial outcomes have been accompanied by widening gaps in health, favouring the dominant culture and disempowering those already disadvantaged. Cross-border or multinational decisions take little account of local needs and local voices with little negotiating power, and this exacerbates the cycle of disempowerment by invalidating cultural traditions, eroding the cultural scaffolding that supports health and wellbeing. When this occurs there is a polarised society; one group dominates and the other is left to feel like the ‘other’.

Although progress has been made towards acknowledging the role of culture in health, this has only resulted in small improvements in health outcomes for Indigenous people.

Although small steps have been made towards heightening public awareness of the role of culture in health, these have been only marginally effective in improving health outcomes. To advance multiculturalism, societies need to institutionalise understanding and tolerance of one another’s cultural beliefs and practices in the context of daily living, and in planning for a future in which all cultures will be sustained. Not many societies achieve this level of equity, but it is seen to be an aspiration worthy of just and civil societies. Canada is the only country in the world to have a national multiculturalism law, which was devised in 1971 as an attempt to legitimise the need for harmony among Indigenous and non-Indigenous groups and those who migrated to Canada from other countries (Kulig 2000). This law enshrined equality, diversity and dignity for all people, and confirmed the rights of Canada’s Indigenous peoples and the status of the country’s two official languages: French and English. Although some have criticised the state of multiculturalism in Canada on the basis that mandating tolerance does not create real understanding, establishing the legal framework was an important step in creating awareness of the need to understand and embrace diversity for the benefit of all society (Kulig 2000).

Ethnocentrism to racism

Ethnocentrism is the tendency to view the world through one’s own cultural filters, perceiving and interpreting others’ behaviours according to our belief system and behaviours (Matsumoto & Juang 2004). Each of us views the world through the cultural lens with which we have been socialised, and this is why it takes a conscious effort to really ‘see’ other cultures. When people develop an aversion to the very notion of tolerating other cultures, they are described as xenophobic; fearing and despising those who differ. Xenophobia is often used synonymously with racism, which is a belief in the distinctiveness of human races, usually involving the idea that one’s birth-ascribed race or skin colour is superior to another (Eckermann A, Dowd T, Chong E, Nixon L, Gray R, Johnson S, 2006 and O’Brien A, 2006). Maintaining feelings of superiority about another race, or another group, is called stereotyping. These feelings can lead to prejudicial attitudes, which, when acted upon, result in discrimination. Discrimination is shown by speaking against the other person or group, excluding or segregating them, committing acts of violence against them, or, at its extreme, exterminating them as occurred in World War II and in other wars and conflicts.

Today, because of numerous inquiries into historical examples of aggression against one culture by another, we have come to recognise ethnic cleansing as an offensive, prejudicial, act of violent discrimination. This is also racist. When offensive behaviours are entrenched in socio-legal structures or scientific research, the notion of biological inferiority can lead to scientific racism. This occurs when one group is attributed with inferiority on the basis of race, often justified by comparative studies that seek to investigate differences, rather than commonalities (Browne A, 2005, Eckermann A, Dowd T, Chong E, Nixon L, Gray R, Johnson S, 2006 and Puzan E, 2003). It is important that students, academics and practitioners who either generate, or use scientific evidence, recognise this type of racism as embedded in research approaches that are conducted from a ‘white’ standpoint (Fredericks B, 2008, Martin-McDonald K, McCarthy A, 2007 and Puzan E, 2003; Wilson & Neville 2009). Systemic bias occurs where research is conducted ‘on’ instead of ‘with’ Indigenous people. This research approach perpetuates inequality and imbalanced power relations, and we discuss this further in Chapter 12 in relation to research approaches. Institutional racism operates at the level of legal, political and economic organisation in a society, and it creates the impression that, because power dominance is exerted by essential and respected forces in society, it is somehow tacitly acceptable (Eckermann et al 2006). Systemic bias allows one group to dominate another through the predominant social order, where organisational and communication skills, financial resources, and commitment of those involved in running a system, are able to exclude others, making them dependent on the powerful group rather than allowing them full participation (Eckermann A, Dowd T, Chong E, Nixon L, Gray R, Johnson S, 2006 and Toussaint S, 2003).

When the health of Indigenous people is analysed according to norms established in non-Indigenous populations, the health care system is at risk of perpetuating systemic bias.

Health care systems are often accused of systemic bias. This can occur when the health of Indigenous people is analysed according to norms established in the non-Indigenous population, or when the blame for social and health problems is attributed to cultural characteristics instead of inequities in the health care system (Browne 2005). Explaining Indigenous ill health on the basis of culture can lead to health decision-making that stereotypes and therefore excludes some Indigenous people from certain treatments because they have multiple risk factors. It can also be detrimental to health; for example when a person’s refusal of treatment is described as a lack of adherence, when it could be due to communication difficulties, or when a child is refused treatment because of a lack of consent from her/his parent, in a case where the child may be in the custody of relatives (Australian Medical Association [AMA] 2007).

A common stereotypical pattern of systemic discrimination lies in the way women victims of violence and child victims of sexual abuse are dealt with in the health care system. In many cases, the injuries and need for ongoing therapy and emotional support are dismissed by broad-brushing the problem as a cultural one, when the victim’s needs for protection and care are personal and intense. When victims of violence are differentiated on the basis of Indigenous versus non-Indigenous, the media screams ‘culture’, and cycles of discrimination are re-launched by conflating culture and race (Anderson et al 2003). This socially exclusive differentiation leads to alienation of the victim and her people. Another group of Indigenous people are then disempowered and disengaged from society, leading to disorientation, helplessness, powerlessness and ‘normlessness’ (Durie M, 2004 and Eckermann A, Dowd T, Chong E, Nixon L, Gray R, Johnson S, 2006). The lack of a treaty for Australian Indigenous people is also an anomaly that has left Indigenous people feeling alienated. Without a legal status that entrenches rights and responsibilities, there is no framework for progress and no recognition of their contribution to society (Couzos 2004).

Aboriginality, culture and health

The term Aboriginal refers to the initial, or earliest, inhabitants of a place. They are also described as First Nations, or Indigenous, people. However, as mentioned previously, Indigenous people have diverse subcultures and worldviews. Members of different groups also have different influences on their lives, many as a result of their environment. Like non-Indigenous people, those who live in a remote area have substantially different experiences of health from their kin in urban, or other rural settings. Likewise, those who live inland have different health opportunities from those who live close to the sea. The influences on their health are shaped by different determinants beyond biology, age, gender, education, socio-economic status, family membership or neighbourhood. In some groups, cultural knowledge may prescribe diet and eating habits, child-rearing practices, reactions to pain, stress and death, a sense of past, present and future, community and economic structures, responses to health care services and practitioners, and which behaviours are considered a violation of social norms.

The most distinctive feature of Indigenous cultures is a holistic, ecological, spiritual view of health and wellbeing. This encompasses physical, mental, cultural, and spiritual dimensions of health, and the harmonised inter-relationships between these and environmental, ideological, political, social and economic conditions (Eckermann A, Dowd T, Chong E, Nixon L, Gray R, Johnson S, 2006 and Lutschini M, 2005). At the centre of Indigenous people’s relationship with each dimension of health is a fundamental spiritual connection with land, symbolising the ecological connection between health and place.

The physical, mental, cultural and spiritual dimensions of health are fundamental to Indigenous understandings of health and wellbeing.

Indigenous people’s relationships between health and place

The spiritual relationship with land is a metaphysical connection, governing all other inter-relationships. The land is typically described by Indigenous Australians as ‘Country’, which is the place that gives and receives life and is part of the support cycle of life–death–life (Kingsley et al 2009). Indigenous Australians ‘talk about Country in the same way that they would talk about a person, they speak to Country, visit Country, worry about Country, feel sorry for Country and long for Country’ (Australian Heritage Commission, in Kingsley et al 2009:291). For Indigenous people, the spiritual connotation of caring for Country links people with their ancestors. This is a different concept of land from the non-Indigenous understanding, where land is considered an empty space to be ‘tamed’ or worked (Kingsley et al 2009). New Zealand Māori also articulate a connection with the land. The land historically provided the sustenance necessary for life, but it is also the spiritual, cultural and ancestral home for Māori. This relationship is based on the worldview that ranginui (sky father), and papatuanuku (earth mother), are the primal parents from whom all Māori descend. Māori refer to themselves as tangata whenua (people of the land), which captures the spirit of this kin relationship making the people and the land inseparable (www.foma.co.nz/about_māori/māori_land.htm [accessed 26 February 2010]). Platforms for Māori health are considered to be:

… constructed from land, language, and whānau; from marae and hapū; from Rangi and Papa; from the ‘ashes of colonisation’; from adequate opportunity for cultural expression; and from being able to participate fully within society.

(Durie 2001:35–6)

What Indigenous and non-Indigenous people have in common is the concept of ‘biophilia’, a construct that reflects how human beings are innately connected and attracted to the natural environment (Kingsley et al 2009). This connection gives meaning and purpose to life, and it can improve health and wellbeing (Kingsley et al 2009). Kingsley et al’s (2009) interviews with traditional custodians of their lands revealed that for some people, this connection is vital in fostering mental and spiritual health. One of the custodians reported that the land ‘speaks to you … allowing you time to look within yourself … to be grounded … to hear’. Another explained her connection as an affinity towards the land, a sense of belonging. Others described the land as being intrinsic to identity, a way of connecting with culture with a sense of pride, and engendering a sense of responsibility to preserve traditional lands. Importantly, this group of people advocated a return to Country for young people having difficulties in urban living. They felt that working on Country was good therapy for those who were ‘numb from the city’, dislocated from society’ or needing empowerment (Kingsley et al 2009:296).

The close connection with land is what distinguishes the Indigenous ‘holistic’ view from other common perceptions of holism (Lutschini 2005). Holism is acknowledged in the biomedical literature and its scientific foundations, typically referring to an all-encompassing, comprehensive set of factors that contribute to health. An Indigenous worldview with its connection to Country is where an Indigenous person’s life is steeped in the events and stories of their lives (Belfrage 2007). The uncritical way non-Indigenous policy-makers and health planners understand Indigenous ‘holism’ is problematic when it is seen as a biomedical concept, and translated into strategies for health and health services without deeper understandings of this holistic worldview (Lutschini 2005; Richmond & Ross 2009). Yet, few explanations have emerged in the research literature as to how removing Indigenous people from their lands (environmental dispossession) can undermine and reduce the quality of other social determinants of health (Richmond & Ross 2009).

|

Colonisation and disconnection between health and place

In many nations, including Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the US, Indigenous people were displaced from their lands by colonising invaders. Colonisation, and the subsequent political decisions that followed, have disrupted Indigenous people’s connection between health and place, leaving generations of Indigenous people feeling dispossessed of their place, symbolically, geographically, and politically (Eckermann A, Dowd T, Chong E, Nixon L, Gray R, Johnson S, 2006, Pomaika’I Cook et al., 2005 and Richmond C, Ross N, 2009). Breaking the bond that connected Indigenous people to their traditional lands and environments eroded their identity, their culture, and ultimately, their health and wellbeing. This disconnection has created an imbalance that threatened the health of the community (Richmond & Ross 2009). A further level of disconnection was experienced by those who were subjected to intensive missionary activity and taken to residential schools to enforce assimilation into the dominant culture. Part of this assimilation was to extinguish cultural practices by punishing certain behaviours, including dances, ceremonies, language and songs, many of which tied Indigenous people to features of their lands, and the symbolic importance of water, animals and plants (Richmond & Ross 2009). Where once they had been self-governed, colonial laws forced them to abandon their traditions and self-determination, and become subservient to colonial institutions and laws (Richmond & Ross 2009). Dispossession from land and Country is therefore one of the most critical issues that must be dealt with meaningfully if Indigenous people are to develop and enhance their capacity for health.

Displacement from the land by colonising invaders has had a profound impact on the connections Indigenous people have with their environment, resulting in an imbalance that threatens health.

The colonisation history of Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the US reveals a belief by their white European conquerors in their superiority over the native people. In most cases, this view was so extreme that the early explorers dismissed the very presence of Aboriginal people as irrelevant, because they failed to use the land in a way that would be expected in a civilised country. The colonisers thus declared the respective countries Terra Nulliusan empty, uninhabited land, belonging to no one (Australian Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social and Eckermann A, Dowd T, Chong E, Nixon L, Gray R, Johnson S, 2006). In Australia, this belief represented institutionalised racism, given the colonisers’ view that land not cultivated represented a failure of Indigenous people to use the land, a mark of ‘civilisation’ according to British/European culture. Their colonisers were therefore able to claim the land without having to conquer Indigenous people or negotiate a treaty with them (Eckermann et al 2006). This is different from the situation in North America and New Zealand, where treaties have been established as a mark of socio-legal commitment between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people.

The Treaty of Waitangi, signed in 1840 but not honoured and recognised until the 1970s, was established to protect Māori cultural beliefs, practices and intellectual life and provide equitable access to the benefits of modern life (Turale S, Miller M, 2006 and Wilson D, Neville S, 2009). Treaties established in Canada and the US, have also enshrined mutual obligations between Indigenous people and the governments, although these were originally developed as a foundation for assimilation and colonial control (Richmond & Ross 2009). The lack of a treaty and the difficulties surrounding land rights are significant issues for Australian Indigenous people. Native title, that is, acknowledgement that Indigenous people were the original owners and custodians of various lands in Australia, was granted after a 10-year legal battle by Eddie Mabo. Mabo’s legal challenge disputed the doctrine of Terra Nullius; that the country was unsettled prior to the Europeans coming (Eckermann et al 2006). As a result of the native title acknowledgement, Indigenous people’s spiritual connection to land remains inalienable, which means the land cannot be sold. However, native title also prevents individual Indigenous people from using land as an asset from which to build economic capital or bargain authentically in the economic arena. Tortuous government red tape continues to mitigate against resolving the issue of land rights, with successive governments lacking the political will to honour the original inhabitants of the country.

The issue of land rights for Indigenous people is being addressed in different ways by different countries but the commonality is a persistent attempt by non-Indigenous cultures to limit the rights of Indigenous cultures to make claim to the land.

The land rights issues in Australia are different from the New Zealand situation. In New Zealand, the Māori Land Court holds much of the written information on Māori land ownership and the historical connections that exist between iwi, hapū, whānau and the land. The Māori Land Court was established as the Native Land Court in 1865 in order to define the land rights of Māori and to translate those rights into land titles recognisable under European law (www2.justice.govt.nz/māorilandcourt/pastpresent.htm [accessed 26 February 2010]). The functions of the Māori Land Court today are to promote the management of Māori land by its owners by maintaining the records of title and ownership information, to contribute to the administration of Māori land, and to preserve taonga Māori (www.justice.govt.nz/māorilandcourt/pastpresent.htm [accessed 26 February 2010]).

Colonisation also brought environmental destruction from over-grazing, and the destruction of grasslands and forest, with its edible seeds, roots and fauna, all of which have been a personal affront to Indigenous people. The destruction of Indigenous habitats destroyed the metaphysical connections between people, their Country and their family. As in ancient history, Indigenous systems of resource ownership and exchange were intended to provide the opportunity to develop autonomy and mastery over life, and to help young men especially with culturally appropriate identity formation and social integration (Burgess C, Johnston F, Bowman D, Whitehead P, 2005, Mignone J, O’Neil J, 2005 and Pomaika’I Cook et al., 2005). Destroying their ability to accomplish these connections, and to manage natural resources in an Indigenous way has disrupted cultural continuity for young people and adolescents, and the very essence of Aboriginality. It has also created a ‘cultural trauma syndrome’, a violation of selfhood where disenfranchised individuals take on the role of perpetrator, inflicting cultural wounds on others, leading to intergenerational transference of their grief rather than resolving it in culturally appropriate healing (Pomaika’I Cook et al 2005:119).

Culture blindness and the Stolen Generations

In 1997 the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC) published a report of the National Inquiry into Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from their Families (HREOC 1997). The Inquiry found that approximately 8% of Indigenous Australians age 15 or over had been forcibly removed from their natural family. The result was mass undermining of Indigenous social organisation, dispersal of geographic groupings and the capture of Indigenous women (Eckermann et al 2006). Their displacement was accompanied by sexual abuse, the introduction of alcohol, and economic and environmental exploitation, which was further demoralising. Then, ludicrously, Indigenous people were blamed for being demoralised and living in squalor — a classic case of what we now call ‘victim blaming’ (Adelson N, 2005 and Eckermann A, Dowd T, Chong E, Nixon L, Gray R, Johnson S, 2006). The dislocation of the ‘Stolen Generation’ has been linked to a range of negative outcomes, including higher rates of emotional distress, depression, anxiety, heart disease, and diabetes, as well as cultural detachment (Trewin & Madden 2005). Many have had contact with mental health services, or lived in households where there were problems caused by gambling, or overuse of alcohol. An intergenerational effect is evident in the fact that the children of those who had been forcibly removed from their homes were more than twice as likely to be at high risk of clinically significant emotional or behavioural difficulties, and approximately twice as likely to use alcohol and other drugs compared with those who had not been forcibly separated from their family (Zubrick et al 2005).

Point to ponder

Approximately 8% of Indigenous Australians over the age of 15 years were forcibly removed from their natural families.

The separation of Indigenous children from their families has also perpetuated racism and culture-blindness. Removing young Indigenous children from their parents, and sending them to ‘white’ schools to gain what was considered to be ‘appropriate’ educational preparation was a culture-blind policy that traumatised Indigenous people and the place of family as the epicentre of life. When this occurred in the last century, Australian Indigenous children who were light-skinned were primary targets for removal, conceivably to protect them from abuse by their family members and other Indigenous people who rejected them as being neither black nor white. The children who were removed grew up in white missions and schools presuming that no such family existed, and often were subjected to inter-racial aggression. Women and children became victims of exploitation and sexual abuse, and most suffered the emotional cost of being confined for prolonged periods, whether in institutionalised housing, or hospitals. The parallel situation with refugees being held in detention is remarkable. Both groups suffer ongoing, severe, intergenerational traumatisation. The consequent loss of freedom and space has a lasting effect that is not easily resolved.

The health of Indigenous people throughout the world

There are approximately 350 million Indigenous people in the world, representing more than 5000 cultures in 72 countries (WHO 2007). For all of these groups, life expectancy at birth is approximately 10–20 years less than the rest of the population; infant mortality is 1.5–3 times greater than the national average, and a large proportion suffer from malnutrition and communicable diseases (WHO 1999). In many regions of the world, the health of Indigenous people is also threatened by damage to their habitat and resource base (Harlem Brundtland 1999). Indigenous people’s burden of illness, injury and disability is so disparate from that of non-Indigenous people, that in 1999, the WHO convened a meeting with Indigenous representatives from many countries, to develop the Geneva Declaration on the Health and Survival of Indigenous Peoples (WHO 1999). The objective of the declaration was for Indigenous people throughout the world to reaffirm their right of self-determination, and to remind states of their responsibilities and obligations under international law to help address these. Their statement placed responsibility for Indigenous ill health on colonial negation of their way of life and worldview, the destruction of their habitat, the decrease of biodiversity, imposition of substandard living and working conditions, dispossession of traditional lands and the relocation and transfer of populations (WHO 1999). The Geneva Declaration was followed by the United Nations (UN) Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UN 2007). The WHO’s commitment to Indigenous people was reaffirmed in the 2008 report ‘Primary health care: now more than ever’, which reminded health service providers that many Indigenous people continue to be disadvantaged by their remoteness and lack of health services (WHO 2008).

In 2007, the United Nations affirmed their commitment to the rights of Indigenous people with the signing of the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Interestingly, among those nations not signing the Declaration were Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States. Australia and New Zealand subsequently ratified the Declaration, but controversy over ratification continues in New Zealand.

One of the most common outcomes of the dispossession and demoralisation of Indigenous people is incarceration. The destructive effect of confinement on the balance of Indigenous family and community life has always been underestimated, and only recently has become recognised as a powerful and enduring influence on Indigenous people’s sense of alienation from their land and erosion of their spiritual identity (Kingsley J, Townsend M, Phillips R, Aldous D, 2009 and Richmond C, Ross N, 2009). Until colonial powers established prisons, Indigenous people enacted their own form of tribal justice. Imprisoning people to try to deal with violence, and fighting violence with violence, have had a backlash effect. They have failed to reduce crime or conflict, and instead, have left many families fatherless (Cripps & McGlade 2008). Attempts at assimilation have also failed. Trying to force non-Indigenous culture on Indigenous people in the guise of protecting them, has been utterly destructive around the world, and has led to dispossession and displacement (Adelson N, 2005 and Eckermann A, Dowd T, Chong E, Nixon L, Gray R, Johnson S, 2006). As a result, Indigenous people continue to be the most disadvantaged and marginalised members of the community. Although we have just drawn attention to the fact that these groups are widely diverse, it is important to draw the attention of health planners and policy-makers to the extraordinary constraints on their capacity to become empowered and achieve the health status to which they are entitled.

The health of Australian Indigenous people

Of the nearly 20 million people in Australia, close to half a million (2.5%) are Indigenous; Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islanders (AIHW 2008). Compared to non-Indigenous Australians, Indigenous Australians are less healthy, die at a much younger age, have more disability and a lower quality of life (AIHW 2008). More than twice as many Indigenous infants die at birth, or are born with low birth-weights. Morbidity and mortality rates for Indigenous people are imprecise, because of the potential to misclassify or under-report Indigenous status, but, compared with non-Indigenous people, the mortality figures for Indigenous people are startling (Draper et al 2009). Existing data show twice the all-cause rates of death for both men and women, with many more deaths occurring before age 65 (AIHW 2008). The gap in life expectancy between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians has drawn considerable attention from the Commonwealth government, with ‘closing the gap’ becoming a centrepiece of policy development. In 2008 the gap was declared to be 11 years, a reduction from the figure of 17 years used by the previous government. However, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), the figures are dubious, given a radical change in the calculation methods (Hudson 2009). As a result, it is unclear whether the reduced ‘gap’ in life expectancy is real, or an artefact of the counting method. Irrespective of which figure is used as a benchmark, closing the gap continues to be a major focus of Australian government policy, and a stimulus for health planners.

More than twice as many Indigenous Australian infants die at birth or are born with low birth-weights than non-Indigenous Australian infants.

The causes of illness and disability for Indigenous Australians are similar to that of non-Indigenous people, including cardiovascular diseases, mental disorders, chronic respiratory disease, diabetes and cancer. Indigenous people are also over-represented in the incidence of chronic illness, not only because of the difficulties of accessing health services, but because of the lack of a healthy start to life. Many Indigenous people who are now middle aged were low birth-weight infants, and therefore have lived their lives with both biological and social disadvantage. The disproportionate distribution of these, largely preventable causes of ill health, contributes 77% to the difference in life expectancy between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people (Zhao et al 2008). In addition, one-quarter of Indigenous Australians live in remote or very remote areas of the country, which adds another level of risk to their burden of ill health, because of a lack of health services, and exposure to some communicable diseases prevalent in remote communities (AIHW 2008). Remoteness also affects older people. Indigenous Australians enter aged care at a younger age than non-Indigenous Australians because of their poorer health status.

As a group, Indigenous people have lower incomes, higher rates of unemployment, lower educational attainment, and lower rates of home ownership than non-Indigenous Australians. A high level of socio-economic disadvantage creates greater health risk factors, such as smoking, alcohol misuse and exposure to violence. These factors are also linked to overcrowded housing conditions, particularly in remote areas. Overcrowding is a challenge for those who wish to refrain from smoking or alcohol use, when others are engaging in these behaviours. Crowding and poorly maintained homes also prevent people from engaging in the fundamental elements of hygiene that would help prevent infections, especially in young children (McDonald et al 2009). Substandard living conditions also present barriers to developing parenting practices that would help reduce the high rates of childhood infectious disease, poor growth and low cognitive outcomes that have plagued Indigenous children in many remote areas (McDonald et al 2009). Living closely with others also makes it difficult for parents to go against traditional social norms of hygiene, or other parenting practices. Consequently, families living in these conditions have neither the freedom to protect their living space from the poor hygiene of others, or appropriate role models to secure even the basic healthy living practices outlined below in Box 11.1 (McDonald et al 2009).

BOX 11.1

Inadequate housing and overcrowding have attracted few effective interventions. A multidisciplinary team of researchers from South Australia attempted to analyse the issues surrounding housing problems, compiling a list of basic healthy living practices that are linked to housing safety and the environments within which people are expected to keep their families safe and healthy in remote areas (Torzillo et al 2008). These are as follows:

1 washing people, especially children

2 washing clothes and bedding

3 removing waste safely

4 improving nutrition

5 reducing the impact of crowding

6 reducing the impact of animals (dogs) as vectors of disease

7 reducing the impact of dust

8 improving temperature control

9 reducing minor trauma (Torzillo et al 2008:7).

The research team adopted an ecological approach, investigating the ‘health hardware’ and maintenance processes available in the environment to support healthy living practices. They found that electricity was unsafe. It was impossible to wash a child in a tub or bath. A functioning shower was available in only 35% of houses. Only 6% of houses had adequate facilities to store, prepare and cook meals. Their data dispelled the myth that it is Indigenous people who create damage, and ‘house failure’. They developed a set of recommendations for regionally planned housing projects with maintenance processes integrated into funding mechanisms. Their logical conclusion, supported by other researchers, is that health education and health promotion programs will not be successful, unless combined with sustainable developments in health hardware that will help enable a healthy home environment (Commonwealth of Australia, 2007, McDonald E, Bailie R, Grace J, Brewster D, 2009 and Torzillo et al., 2008). This important study underlines the need to peel back the layers of environmental factors that support or prevent people’s attempts to achieve health and wellbeing.

The health of New Zealand Māori

At the last New Zealand Census (2006), people identifying with the Māori ethnic group made up 15% of the total population — up 7% since the previous census in 2001. Māori are a youthful population, with a median age of 23 years, compared to 36 years for the total population. Māori predominantly live in urban areas of the North Island, although are more likely to live in minor urban areas, with a population between 1000 and 9999, than non-Māori. Māori life expectancy also varies substantially from non-Māori. Māori women have a life expectancy of 75.8 years compared to 82.8 years for non-Māori, and Māori men have a life expectancy of 71.2 years, compared with 78.8 years for non-Māori men. This gap has been reducing, moving from 9.8 years in 1995–97 to 7 years in 2006 (Ministry of Health New Zealand [MOHNZ] and Minister of Health 2008). Despite these improvements in life expectancy, on average, Indigenous Māori have the poorest health status of any ethnic group in New Zealand (King & Turia 2002). Compared to non-Māori, inequalities in health status and mortality are large and increasing, with conditions such as coronary heart disease occurring at an earlier age, and with higher fatality rates (Tobias et al 2009). Major causes of mortality for Māori include cardiovascular disease (33% of all Māori deaths), cancer (25%), respiratory disease (8%), accidents (8%), diabetes (7%) and suicide (3%) (Robson & Purdie 2007).

Large disparities exist between Māori and non-Māori determinants of health. In 2005, 49% of Māori secondary school students left school without a qualification, compared to 22% of non-Māori; unemployment rates remain three times higher than that of non-Māori; the median annual income for Māori in 2006 was $20900 compared with $24400 for the total population. In 2004, 40% of Māori families were living in hardship, compared to 19% of non-Māori families. Māori are also more likely to be living in overcrowded housing environments than non-Māori (Robson et al 2007a). Young Māori men are more likely to be arrested for minor offences than non-Māori, and are more likely to be referred to the courts, rather than directly for family group conferences (Robson et al 2007a). These factors, along with evidence of the existence of differential access to health care, and of racial discrimination in health care (Reid & Robson 2007a), serve to further disadvantage Māori as they attempt to redress the factors that contribute to poor health.

The Treaty of Waitangi provides the basis from which Māori have the right to self-determination, and the right to name themselves as tangata whenua (people of the land), and be recognised as such (Reid & Robson 2007). As mentioned previously, it was not until the 1970s that the New Zealand government acknowledged that significant breaches to the Treaty of Waitangi had occurred. As a result, the Crown began to implement a number of policies that sought to address some of the inequities suffered by Māori since the arrival of European settlers in the early 1800s. These included revamping the Māori Land Court, as mentioned previously, and establishing the Waitangi Tribunal. The Waitangi Tribunal was established in 1975 in order to make recommendations on claims brought by Māori relating to actions or omissions of the Crown that breached the promises made in the Treaty of Waitangi (www.waitangi-tribunal.govt.nz [accessed 26 February 2010]). Claims against the Crown continue to this day, and although the Waitangi Tribunal does not have final authority to decide points of law, it has made recommendations in over 100 reports on claims and a range of settlements have been made (www.waitangi-tribunal.govt.nz/reports [accessed 26 February 2010]).

Māori have a life expectancy of 73.5 years at birth compared to 80.8 years for non-Māori.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree