5.1 How can it help?

Critical appraisal offers a way through the huge volume of material now being published. There are over 6000 journals on the ISI science journal citation report database (http://wok.mimas.ac.uk) and most of these publish hundreds of articles each year. Only a small proportion of these will be relevant to your particular field of interest, but nevertheless, there will still be numerous journals you could be looking in either monthly or weekly to keep up to date in your field. This will result in many papers that interest you but only a small number that will really change your practice. Critical appraisal helps you decide how applicable the research is to ‘real life’ situations and whether it will help improve your clinical practice.

Equally, when searching the literature for the background to a study you will find a mixture of good and bad studies; the bad studies are not helpful in developing your study protocol. It is important to evaluate the evidence already available when refining your research question and designing your study; additionally, funding bodies and ethics committee will certainly ask you for an evaluation of the published literature in your area. Critical appraisal will help you sort the wheat from the chaff.

5.2 How do I critically appraise research papers?

There is no one absolute method of critical appraisal; different people structure critical appraisal in different ways. The method presented here is one approach that many people have found helpful and easy to follow and is based on the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP© Milton Keynes Primary Care Trust 2002) and the Users’ Guides to the Medical Literature published in the Journal of the American Medical Association. However, there are plenty of other resources available to guide you and some of these are listed at the end of the chapter.

There are three basic areas to consider for all papers:

Message: what are the main results and conclusions of the article?

Message: what are the main results and conclusions of the article? Validity: can the results and conclusions be justified based on the description of the methodology and findings?

Validity: can the results and conclusions be justified based on the description of the methodology and findings? Utility: is the research relevant to the study I am planning? Will the results be applicable to my patients?

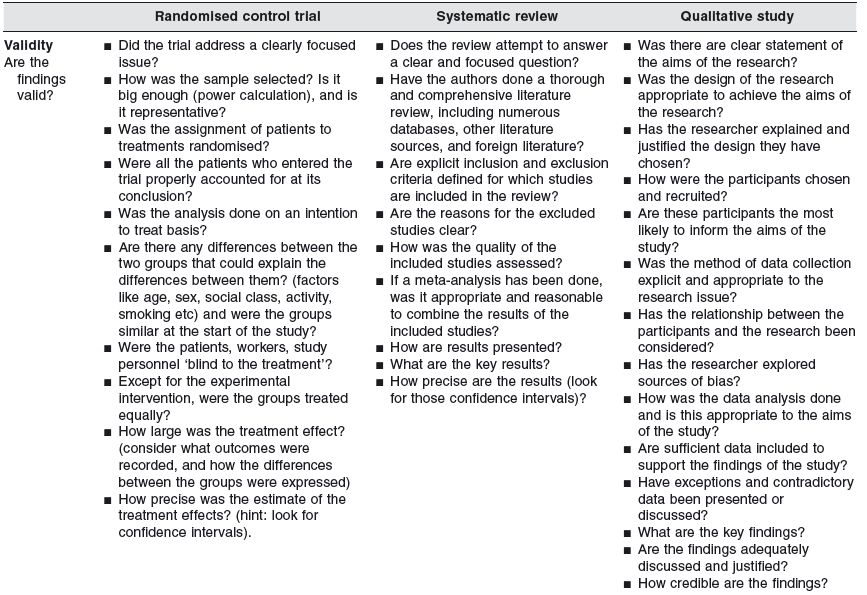

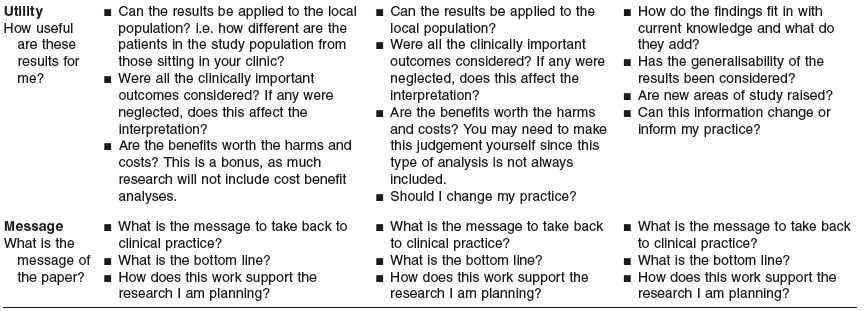

Utility: is the research relevant to the study I am planning? Will the results be applicable to my patients?The specific questions you need to ask yourself about each paper will depend on the design and methodology of study you are appraising. Examples of the sort of questions you need to ask about a randomised control trial, a systematic review and a qualitative study, within each of the three major areas are listed in Table 5.1.

Table 5.1 illustrates that the main area for consideration when assessing the quality of the paper is the methodology. If this is sound the results are also likely to be robust and you can then draw your own conclusions before reading the discussion, to see if you agree with the paper’s authors. The questions to ask about the validity of the paper vary the most between study designs but you should always start by looking for a clear and explicit research question or study aim. Further detail on questions to ask about other study designs (cohort, case control, etc.) can be found by using the resource section at the end of this chapter. The questions to consider about the utility and the message of the paper are fairly similar whatever the study design. More detail on how to identify different study designs is given in Chapter 6.

When you are reading research papers start by looking for the research question (hypothesis or study aim), which is usually at the end of the introductory section. Next work your way through the methods section by looking for the answers to the questions appropriate for the design. At any point, if the answers to these questions are poor, you need to consider whether it is worth continuing – Is this paper really going to tell you anything useful at all? Is it better to leave this paper and read another instead?

You are trying to use critical appraisal as a method to filter through the mass of literature available, so do just that. Be critical and be sceptical. If the information is not there, do not assume the research has been carried out in the best way. If all the results are not reported – perhaps it is because they do not support the hypothesis. Look for inconsistencies. Do not assume that just because it is published in a peer reviewed journal it must be useful. If you think the paper is not useful, leave it and move on.

Having emphasised the need for a healthy dose of scepticism, it is important not to take this strategy to extremes. Almost any human study can be criticised in one way or another, so do try to take a balanced view and think about whether the research could have realistically been done in a better way. Think carefully about whether the flaws you identify are likely to significantly affect the final results before you reach a conclusion on the paper. Ideally, your approach to critical appraisal is one which takes a measured, balanced view. Walk a line between the extremes of assuming that every research paper is written by a pathological liar and must be torn apart, and the opinion that because papers are published they must be good and are beyond reproach.

Table 5.1 Examples of the type of questions you need to ask about three different study designs.

5.3 Other things to think about

There are other aspects of study design and research governance that you may also consider as you review papers. For example, how would you regard the report of a project funded by a company who marketed some of the drugs or equipment involved? There is evidence of publication bias in pharmaceutical and nutrition research so this is worth considering (Bekelman, Li & Gross 2003; Lesser et al. 2007).

What about ethics? Would you use the results of a study where you felt there were ethical problems and no explicit evidence of Ethics Committee approval? Although many biomedical journals now require clear evidence of ethical approval before publication, evidence suggests ethical issues can still arise (Bauchner & Sharfstein 2001) and there is continuing debate in the medical literature about ethics in research.

5.4 Appraising the statistics

Critical appraisal of the statistics used in the research is important but many people find this daunting and have little confidence in their skills in this area. You do not have to be a mathematician to appraise the statistics but you will need an understanding of the fundamental principles of probability and risk assessment. Much of the fear induced by the statistics is due to unfamiliar terminology; tackling a host of incomprehensible jargon is overwhelming and difficult. Nevertheless, you have to start somewhere and take that first step to learning the terms involved. Chapter 8 has been written to get you started with statistics.

When reading and appraising papers start by looking at the description of the statistics used and try to understand why certain tests have been chosen (more on this in Chapter 8). Next focus on the main results (look for the primary outcome measure the researchers have used – see Section 7.2.6.5) and work through what the figures are telling you. See if your interpretation of the figures matches that of the authors. Next, look at the other data presented and see if they help explain or clarify the main results.

Finally, beware of ‘statistically significant’ results that are not ‘clinically significant’. Statistical significance means that we can be confident the result is true, but clinical significance means the result will make a difference to the treated patient. For instance, a new physiotherapy exercise intervention compared to the usual practice may show a ‘very significant’ (p < 0.001) improvement in the ‘timed up and go’ test, but that difference may be only 3 seconds, which is unlikely to make much difference to the patients’ quality of life. You will need to use your clinical expertise within your area to make this judgement.

5.5 Journal clubs

An excellent way to practise and develop your critical appraisal skills is to regularly attend a ‘journal club’. Critical appraisal skills are not easy and take time to develop as you learn about different study designs and statistics, and refine your analytical skills. The more you practise the better you will get and the quicker you will be able to appraise a paper. The strength of a club is that you will learn together; educating each other and sharing the burden of looking up terms or unfamiliar techniques.

The general idea is that a group of people get together (such as your department or your multi-disciplinary team), choose a paper to appraise and then critique it together. A well run journal club that encourages participation from all is a stimulating and educational experience. However, journal clubs do have the potential to be very dull, a platform for some people to extol their expertise, and can be intimidating to quieter or more junior team members. With care this problem can be avoided, and I describe here a successful approach I have used with a number of therapy professions that has received positive feedback (see Boxes 5.1 and 5.2); this is not the only way and others have described a variety of approaches (Gibbons 2002; Gonzalez 2003; Higgins & O’Gorman 2006).

A schedule for the club is agreed and each person in the team is assigned a date to choose a paper they think would be either interesting or may lead to changes in practice. The chosen paper is circulated to the whole team prior to the club (at least one week before) and everyone is expected to read it. The critical appraisal skills programme tools (CASP tools – see Resource section) are used to help with the appraisal process, and each person comes to the journal club with a couple of questions in mind to ask others about the paper. The questions could be those listed in the CASP tool or it could be a specific issue about the paper.

The organiser for that week chooses one of their questions then picks one of the other participants to answer it. This person attempts to answer the question and engages others in the discussion. This person now asks someone else a question, and so the discussion continues encouraging all to participate.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree