CHAPTER 1 Critical reflection in clinical education

beyond the ‘swampy lowlands’

USING THEORIES TO INFORM CURRICULUM DESIGN AND RESEARCH

When designing health practice curricula that incorporate critical reflection, each of these theories may be used to frame ways to reflect on learning experiences and research. Using reflexivity means the curriculum should provide an opportunity for students to understand how their personal and discipline-specific perspectives impact on their learning or their interaction with others. Using postmodernist perspectives means critical reflection learning tasks should be designed to encourage students to explore and experience alternative views to those of their own health professional discipline. As an underlying theoretical framework, critical theory means the curriculum or research about the curriculum should enhance students’ acknowledgement and understanding of historical and sociocultural views of their own practice and learning experiences within the broader healthcare system.

Introduction

In healthcare practice, thinking reflectively means thinking about and evaluating experiences in order to reach new understandings and perspectives (Schön 1983, 1987, Boud et al 1985). Thinking critically means unearthing deeper assumptions or pre-suppositions about practice (Mezirow 1991, Fook 2004), about power (Brookfield 1995), and about connections between oneself and social contexts (Fook 2004). When these two meanings are combined, ‘critical reflection’ involves a process of both change and challenge to professional practice. Critical reflection, described in this way, also implies that the teaching of critical reflection skills should not be confined to a discrete ‘package’ in health professional education, but rather positioned as relevant and integral to thinking in all aspects of health professional curricula.

Critical reflection, healthcare practice and education

The healthcare context is recognised as an uncertain (Higgs & Titchen 2001), continuously changing (Ryan et al 2003), ‘swampy’ or messy (Schön 1987) working environment. The qualities that health practitioners require to practise in such an environment include being autonomous, confident, self-directed, ethical, flexible, collaborative, inclusive, organised and innovative (Ryan et al 2003). Iedema et al (2004) categorise these personal qualities into three types of abilities. The first is a level of reflexivity about the paradigms of knowledge that underpin specific healthcare practices. The second, an ability to understand and work with other health practitioners, and the third, an ability to articulate complex descriptions of different knowledge domains contributing to health practices.

Higgs and Titchen (2001) similarly outline teaching, learning and practice strategies that are necessary to promote these abilities and to reframe the interface between an uncertain world of professional practice and health professional education. They include:

In recognition of both the clinical practice environment, and the required qualities and abilities that practitioners need to continue to develop as professionals, methods of promoting and teaching skills in critical reflection have received increasing attention in clinical education literature (Higgs & Titchen 2001, Dye 2005, Jensen et al 1990, Maudsley & Strivens 2000, Henderson & Johnson 2002, Trede et al 2003, Cole et al 2004). Teaching skills of critical reflection in health education has been proposed as a means to counter a positivist tendency in health sciences education to present knowledge and clinical skills in terms of measurable mastery and attainment of specific competencies (Kneebone 2002). Thinking critically and reflectively has been identified as one way to counter teaching strategies that rely on uncritical knowledge transfer between teachers and students. This knowledge transfer approach is a feature of experiential learning through an apprenticeship model, where students are exposed to a range of clinical scenarios and conditions through observation initially, and then through supervised clinical practice (McLeod et al 1997, Dornan et al 2007). In this model, there is an emphasis on the learner ‘acquiring knowledge and skills from an expert or master with the goal of emulating their expertise’ (Higgs & Titchen 2001).

Recent critiques of experiential learning and use of apprenticeship models suggest that they focus on building individually based, discipline-specific knowledge, operational competence and outcomes (Rees 2004, Bleakley 2006), and neglect the idea that professional learning and practice involves adaptive, sociocultural and heuristic or interpretive processes (Eraut 1994, Jensen et al 2000, Edwards et al 2004, Talbot 2004, Bleakley 2006). On the basis of these critiques, experiential learning may not be enough to meet the need for health professionals to be flexible, aware and have an understanding of alternative perspectives held by patients, healthcare professionals, hospital administrators and others (Trede et al 2003).

Critical reflection skills are recognised as a response to these critiques because they represent a way of thinking for students and practitioners to analyse the domains of knowledge underpinning their practice and to enable them to learn from, and redevelop, their practice (Kember 2001, Fook 2004). This role has also been reinforced by studies that demonstrate a link between the skills and use of critical reflection and the development of expertise in healthcare practice (Shepard et al 1999, Edwards et al 2004, Dye 2005, Jensen et al 2000).

Critical reflection is therefore seen to have a role in both enhancing the learning process itself and as a means of professional development (Pee et al 2002).

Models of critical reflection

The original proponents of reflection in professional practice refer to a series of steps to follow and an underlying rationale to guide the reflective process. Dewey (1933) described separate phases of problem definition, problem analysis, formulation of a theory of action and then action. The key characteristic of this process is one of careful consideration of actions by delaying initial reactions and developing an understanding of alternative options and perspectives.

Schön (1987) distinguished between different types of reflection by describing the process of reflecting-on-action and reflecting-in-action. The latter category requires practitioners to maintain a sense of curiosity and openness while they practise, to enable them to recognise and challenge their own implicit understanding and interpretation of a clinical situation. Schön’s two types of reflection have been incorporated into various models of reflective practice, designed to provide a structure and process for students to follow.

Baird and Winter (2005) describe three models of reflection to guide teaching and learning strategies that facilitate reflective thinking and practice. The first of these was originally proposed by Boud (1993). In this model, students are encouraged to first identify their personal experiences that act to inform their learning intentions. Second, to describe the clinical learning or practice experience by explicitly building on their own understanding and knowledge. The third and final step involves a re-examination and evaluation of their learning experiences.

The Gibbs (1988) circular model follows six phases. The first two are descriptive. Students are required to describe the learning or clinical event, including their accompanying feelings. This is followed by a two-step evaluative phase, where the value and meaning of the experience is questioned and discussed. The final two steps involve thinking about and articulating alternative actions and planning for future actions in light of the lessons learnt.

Another commonly applied model proposed by Driscoll (2000) is a series of steps. The steps include description, analysis and evaluation. They are similar to the model proposed by Gibbs, with the addition of a seventh step to encourage the student to plan how to put into action the new learning gained from reflecting on the clinical practice experience.

Methods of ‘doing’ critical reflection

Critical reflection has received considerable attention in a range of health professions, including nursing (Howell 1989, Johns 1995), social work (Taylor & White 2000, Gardner 2003, Fook 2004), medicine (Maudsley & Strivens 2000, Henderson & Johnson 2002, Cole et al 2004, Iedema et al 2004), dentistry (Pee et al 2002), occupational therapy (Routledge et al 1997) and physiotherapy (Cross 1993, Larin et al 2005). This body of literature describes two main methods to incorporate reflection into health education curricula.

The most common is via reflective diaries or journals (Larin et al 2005, Dye 2005, Francis 1995, Richardson & Maltby 1995, Routledge et al 1997, Snadden & Thomas 1998, Chirema 2007, Clouder 2000, Cross 1997). One rationale underlying this method is that by setting a structured task of journal writing, students will establish a habit of reflection and be encouraged to develop ongoing skills in critical reflection.

Another common method for encouraging student reflection is through structured verbal feedback sessions between student and educator (Ende et al 1995, Frye et al 1997, Molloy & Clarke 2005). These feedback opportunities are generally integrated into the clinical education curriculum. In these situations, the clinical educator provides feedback about how the student is progressing, and the student is expected to reflect either verbally or via a written self-assessment form about their own learning progress. Within these feedback sessions, clinical educators are expected to facilitate students’ reflective capacity through the skilled use of questions and prompts (see Ch 8). The collaborative generation of insights represents a form of critical reflection of the student’s performance, and is used to guide strategies for improvement, and the setting of new learning goals (Henderson et al 2005).

Studies that describe methods of introducing critical reflection within health professional curricula as either written or verbal tasks, have assessed the outcome and effectiveness of students’ critical reflection on the basis of how critical or analytical the writing is and by how students’ reflections change over time. In the latter category, longitudinally based studies have identified that as students progress through their clinical training, the content of their reflective writing changes from a focus on themselves as learners (Jensen et al 2000, Cross 1993) to a focus and increased insight into the importance of understanding the patient’s perspective (Wessel & Larin 2006). Studies that discuss the outcome of students’ reflective writing in terms of how it demonstrates levels of critique and analysis, focus on the process of reflection (Boenink et al 2004, Pee et al 2002, Henderson & Johnson 2002). Assessment of critical reflection tasks from this ‘process perspective’ measure student reflection on the basis of whether it is (Hatton & Smith 1995):

A further debate about assessment of critical reflection concerns whether or not students’ reflective capacity should be assessed at all (Rose & Best 2005, Cross 1993). The claim against assessment of reflective practice is generally based on the premise that external assessment may constrain honest reflections by students. As a counter to this claim, we suggest that assessment of critical reflection writing provides students with structure for their reflection, feedback on the depth of their reflective capacity, and, most importantly, reinforcement of the integral role that reflection plays in healthcare education and practice. However, students need to be reassured that their reflective writing is not assessed according to the stance or viewpoints they take, but rather their degree of engagement in the process of critical reflection (Driessen et al 2005).

The iterative model of critical reflection

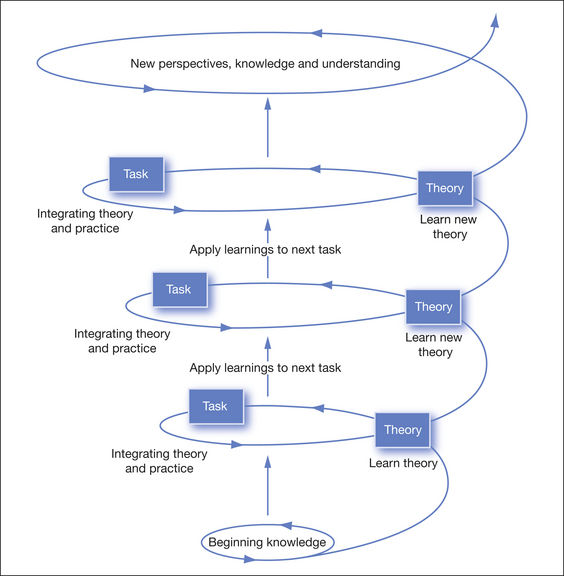

In developing our ‘iterative model of critical reflection’, we aimed to embed the tenets of critical reflection within and across the curriculum. This involved more than setting a series of tasks that facilitated critical reflection. It involved teaching the theories that underpin the steps of critical reflection and promoting the use of these theories as a means for students to individually and personally interpret, apply and develop new knowledge when engaging in new tasks. Using this model, the learning process becomes an iterative one that relies on students going back to underpinning theories to inform their critical reflection tasks in much the same way that they rely on theories of practice to inform their clinical discipline-based knowledge (Fig 1.1).

Our iterative model draws from the work of Fook (2002, 2004) who developed a model of critical reflection in social work practice. Fook (2004) linked ideas of reflective practice with underlying theoretical bases of reflexivity, postmodernism and critical theory. These theoretical perspectives and intellectual traditions provide important underlying explanations for the critical reflection program described in this chapter.

The process of using theoretical principles to inform practice is well established in the science and evidence underpinning healthcare practice (Kneebone 2002, Herbert et al 2005). For example, there is a clear expectation that in order for students to describe the steps involved in assessing an ankle sprain, they need to have an underlying knowledge of theories of the inflammatory cascade, the healing process, and the effect of load on collagen deposition. In the same way, we believe critical reflection tasks that require students to construct, interpret, evaluate and reflect on experiential knowledge, including a range of perspectives, must also be explicated in terms of underlying theories. We contend that this familiarity with, and acceptance of, the theoretical knowledge base that underpins reflective practice, mean that students will more likely develop habits of reflection as an integral component of their professional practice. The model presented in this chapter has been applied and evaluated in a specific critical reflection program for undergraduate physiotherapy students (Delany & Watkin 2008). Student and facilitator evaluation of the program highlighted themes of validation and sharing; a break in clinical performance and a broadening of their spheres of knowledge. These themes resonated with students’ overall experiences of learning in clinical placements, and the research provides some evidence for the inclusion of critical reflection as a valid and worthwhile component of early clinical education.

Theories underpinning critical reflection

Theory one: reflexivity

The idea of reflexivity has traditionally been associated with paradigms of qualitative research (Barry et al 1999, Patton 2002, Hansen 2006) but is increasingly recognised as important in healthcare practice (Taylor & White 2000, Jensen 2005). Guillemin and Gillam (2004, p 269) describe reflexivity in qualitative research as a process involving critical reflection of how the researcher constructs knowledge from the research process. According to Patton (2002, p 65), it reminds the researcher to be attentive to and conscious of ‘the cultural, political, social, linguistic and ideological origins’ of first, their own perspective and voice; second, the perspectives and voices of those they interview; and third, the perspectives of those to whom the research is reported. Reflexivity has clear links with reflective practice because it seeks to increase awareness of how personal values and beliefs interconnect with other perspectives and with social and environmental contexts (Boud et al 1985). Patton (2002, p 66) suggests a number of reflexive questions as a framework to guide ‘reflexive interrogation’ in qualitative research. We have re-labelled (in italics) these questions because they represent questions that are relevant to how reflexivity as a qualitative research construct connects with critical reflection in clinical practice.