Chapter 10 Crisis and loss

Learning outcomes

What constitutes a crisis?

Most people can recall a crisis situation in their lives that made them feel out of kilter with the world, highly anxious and vulnerable, a sense of life being out of control and unpredictable. The death of a friend or parent, being the victim of a crime, physical assault or rape, being part of natural disaster, are examples of life crises. Some types of crisis are classed as ‘situational’ crisis (Aguilera 1998): abortion, child abuse, rape, divorce, chronic physical or psychiatric illness, alcohol and drug abuse, suicide and attempted suicide. Others may be termed ‘maturational’ crisis and are linked to normal stages of development and ageing across the lifespan (Aguilera 1998). Some life crises can be anticipated (natural death of a partner), while others are unanticipated (sudden death following a road traffic accident).

A crisis can be distinguished from a stressful event that may pass quickly, such as an exam. Parry (1990) summarised the most common defining features of a crisis as follows:

Consequences of a personal crisis

A crisis will have a significant impact on the lives of those involved. It can produce great pain, distress and anguish. It can lead to feelings of unreality, uncertainty and isolation. A person in crisis will want to restore the general sense of balance in their life and feel able to cope with life again. The word ‘crisis’ also implies a sense of urgency, a turning point, a time for major decisions (Parry 1990). People in crisis are often in a state of shock. It is a time when their thinking is muddled and their emotional reactions are characterised by feelings of loss, helplessness and hopelessness. They may try to cope with the situation by denial initially but they need to cope in a more effective way in the long run. The role of helpers is to enable clients to cope with the problem and with the feelings the problem has elicited. The type of support offered may be emotional support, practical help, companionship, advice and information (Parry 1990).

A life crisis will stop people completing daily activities and routines. It causes a huge disruption in their lives and often the lives of those close to them. This usually means that the people involved in a crisis must make behavioural, social and emotional adjustments in their lives. These may be temporary or, in the case of a crisis brought about by the onset of chronic illness, enduring adjustments (Caltabiano et al 2002). A crisis can change a person’s life permanently. It can signal the end of a promising academic career, the end of a close relationship, the inability to get married and have children, or it can heighten personal vulnerability. A crisis brings much uncertainty into people’s lives because they cannot foresee how it will unfold.

At a time of acute crisis the physical environment too, such as an emergency room, may be a frightening place for patients and their relatives. The level of noise, technical equipment and activity may be daunting. In casualty, the patient who failed in their attempted suicide may feel guilty for wasting people’s time. The rape victim may feel further exposed and violated. The abused child may be confused and scared and unsure of who to trust. These reactions are unlikely to be helpful at a time of acute crisis. On the other hand, strong supportive structures (families and friends) have been found to aid coping and adjustment following serious physical illness (Caltabiano et al 2002) and are likely to play a role in adjusting following other types of crisis too.

Helping people in crisis is not about taking over (although on rare occasions this may be appropriate) and making them dependent. It is more effective to help them to use their own resources and to be supportive. It is about enabling, not disabling (Parry 1990).

A framework for coping and adapting to crisis

The coping and adjustment effort required may be significant and people differ in how they respond to these circumstances. The upshot of a crisis will depend on how well the person copes, and the coping process will be influenced by the interaction of ‘event’ factors, background factors, physical and social environmental factors. For example, an illness can elicit new and distressing signs such as lack of interest in personal hygiene and an inability to communicate effectively with others. Feeling angry, depressed or guilty after surviving a suicide attempt can be stigmatising for the patient or client and reinforces their desire to hide away from people. Sometimes the disabling effect of medication side effects (such as drowsiness and drooling mouth) can be very embarrassing (Morrison et al 2000).

Some people just seem to possess an ability to find a sense of purpose or quality in their lives in spite of the awful things they come up against at a time of crisis. They can resist feeling ‘helpless and hopeless’ (Caltabiano et al 2002). Other factors that are important include age, personal beliefs, gender, personal maturity, social class and the level of religious commitment that a person holds (Moos & Schaefer 1986). These factors will shape the way individuals respond to crises (see also Ch 8, Theories on mental health and illness).

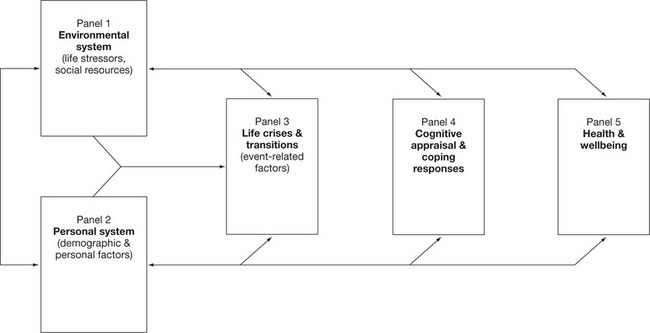

The complexity of issues, responses and settings in which crises and coping occur can be daunting. Holahan, Moos & Schaefer (1996) devised a framework for coping as a process of adaptation by drawing on earlier research and bringing together the need to consider the person and the context in which coping happens. This more general and inclusive model is depicted in Figure 10.1. It takes account of the personal and situational issues that can affect coping. Panel 1 is made up of the constant stressors in life, such as illness, as well as the supports and aids available to the person, while Panel 2 contains the person’s coping strategies and socio-demographic attributes.

These ‘systems’ influence the life crises and transitions that occur to all (Panel 3). The cognitive evaluation of these (Panel 4) has a direct impact on our health and wellbeing (Panel 5). According to Holahan et al (1996), cognitive appraisal and coping responses play a critical role in responses to stress and crisis. It is also notable that the factors in each panel in Figure 10.1 can provide feedback to earlier parts of the framework, giving it a dynamic quality.

Coping strategies have been described within this framework—people typically either ‘approach’ or ‘avoid’ stressful events. This illustrates the person’s orientation. The approach or avoidance domains are also influenced by the methods of coping people can use. These are ‘cognitive’ or ‘behavioural’ methods. When combined, four basic types of coping responses (cognitive approach, behavioural approach, cognitive avoidance, behavioural avoidance) are produced (see Holahan et al 1996 for details).

Of particular importance here is the fact that the research literature indicates that consistent patterns of relationships have been found to occur using this framework. For example: ‘people who rely more on approach coping tend to adapt better to life stressors and experience fewer psychological symptoms. Approach coping strategies such as problem solving and seeking information, can moderate the potential adverse influence of both negative life changes and enduring role stressors on psychological functioning’ (Holahan et al 1996, p 29).

Finally, Holahan et al (1996) also noted that people exposed to crisis events often emerge stronger and with greater levels of competence. Their ability to cope with future crises may be enhanced. They may be more self-assured and assertive, have developed different views of themselves and their abilities, achieved a new sense of purpose in life and become more resilient, in spite of the fact that they have confronted significant life crises. The framework and the findings provide nurses and other care staff with some guideposts for working with people in crisis. They present a structure to ensure that staff consider the wider canvas of events, experiences, resources and coping styles that may be at the client’s disposal with appropriate support and guidance from the nurse.

Events and perceptions that can lead to personal crisis

Slaikeu (1990) described some of the common precipitating events that can spark a personal crisis, including pregnancy and the birth of a child, unmarried motherhood, moving from home to school or from home to university, marriage, bereavement, relocation and migration, retirement, surgery and illness, natural disasters and rapid social and technological change. Other devastating events such as the death of a loved one or rape may elicit a crisis response. Events, even those that most are exposed to, can be interpreted as ‘the last straw’ after a crisis reaction (Slaikeu 1990).

Some time ago Holmes & Rahe (1967) devised a useful way of considering how much stress a person may be exposed to, using the Life Events Scale. The scale lists 41 positive and negative common occurrences that require adjustment and can affect a person’s risk of illness. Each occurrence is given a life-change unit score and these can summed to reflect the level of life-changing events that have occurred in a particular person’s life in the previous twelve months. Some examples include: death of a spouse 100; divorce 73; marriage 50; change in responsibilities at work 29; Christmas 12 and so on. When these are added together a total score can be arrived at; generally the higher the score the greater the risk of illness in the future.

There are no hard and fast rules about what may be deemed a crisis and what may not. A person’s perception of events, their culture and life experience, the consequences and losses associated with these and their ability to manage effectively are primary. Scileppa, Teed & Torres (2000, p 87) commented: ‘Allowing for personal differences in coping styles, it is fair to say that any situation or combination of life occurrence that taxes individuals beyond their typical ability to function can be viewed as a crisis’.

Levine & Perkins (1997) described crisis somewhat differently, as a time when a person’s resources (material, physical, psychological) and those in the person’s social network, are overburdened. The person is unable to deal effectively with the emotions surrounding the event. They may experience feelings of helplessness, anxiety, fear and guilt, and their behaviour is ineffective. Most people cope with crises but sometimes they can lead to other problems such as abuse of alcohol and drugs, or indeed to full-blown psychological or psychiatric illness.

The nature of any nursing intervention at this time may be centred around giving comfort, helping the person to explore their intense feelings, helping to clarify events, options for the future and sources of support—physical, psychological and social—and trying to enhance the person’s coping strategies. If these interventions are helpful then some common outcomes can be expected. The person will feel safe and well supported. Their view of the situation will be couched in reality and they will feel less vulnerable. They will be able to draw on the available sources of support and cope more effectively with the situation.

If the crisis is addressed effectively then this resolution may provide the client with new skills and competencies that can help manage upcoming life crises. If, on the other hand, the crisis is not resolved successfully then this may lead to later problems and issues that have a negative effect on the client’s physical and psychological health. For example, unresolved issues may be the source of later problems in living for many victims of childhood sexual abuse who have been found to suffer from a range of negative consequences later in life, including: depression, guilt, low self-esteem, feelings of inferiority, isolation, loneliness, distrust and poor-quality interpersonal relationships, promiscuity and sexual dysfunction (Johnson 1998).

Intervening at a time of crisis

A crisis can present in many different ways and if it is severe enough, professional helpers may be asked to intervene. Aguilera (1998) described two broad approaches to this process. The generic approach is based on the notion that certain common patterns emerge in most crisis situations and that these must be worked through if the person is to adapt in a healthy way. The intervention is aimed at achieving an adaptive resolution by focusing on the typical patterns of response in crisis rather than the distinctive ways in which individuals react (Aguilera 1998). Hence the approach is a general one focusing on the usual steps and stages that might occur following, for example, the sudden death of a partner.

The individual approach is much more psychological and focuses on the client’s personal history, needs and responses. There is a greater focus on depth and human understanding, and greater levels of specialist training are required to practise in this way (Aguilera 1998). I suspect that practical reality dictates that professional helpers mingle both approaches. The typical steps in a crisis intervention scenario are outlined in Box 10.1 (see also Ch 24).

Box 10.1 Steps in crisis intervention

Source: described by Aguilera 1998.

While these steps may be typical, individuals do not always pass through them in a simple linear fashion. For example, the initial assessment of the problem may be revised as the helper learns more about the client and their life over a period of time. This may change the focus of the intervention, making it more appropriate for the client’s needs. Sometimes the client may set a new direction as they regain a greater sense of personal control over their lives and the coping process. It is notable that a crisis might last between four and six weeks (Aguilera 1998). In addition, many crisis situations are assessed by crisis teams. A fundamental orientation in psychological treatment has been emphasised by Schwartz (2000), who notes that however bizarre the client’s behaviour might appear, they are human beings first and foremost, which demands that they be treated with dignity, respect and compassion. The illness is an important secondary consideration. This orientation is central to all forms of counselling and helping but it is especially important when helping very vulnerable members of society at times of crisis.

Critical thinking challenge 10.1

The first call is from your very good friend. She tells you that she had an abortion this afternoon and can’t stop crying now. You did not know she was pregnant.

The first call is from your very good friend. She tells you that she had an abortion this afternoon and can’t stop crying now. You did not know she was pregnant. The second call comes from the local police, who ask for your immediate attendance at a local hospital where a 22-year-old man is threatening to shoot another resident and then himself.

The second call comes from the local police, who ask for your immediate attendance at a local hospital where a 22-year-old man is threatening to shoot another resident and then himself. The third call is from Joan, a 38-year-old registered nurse who is well-known to the service and has received treatment for depression in the past. She is obviously drunk but says she has taken 30 paracetamol tablets.

The third call is from Joan, a 38-year-old registered nurse who is well-known to the service and has received treatment for depression in the past. She is obviously drunk but says she has taken 30 paracetamol tablets.What course of action would you recommend in each of these cases?

Crisis, loss and grief

Worden (2001) described mourning as the ‘process which occurs after a loss’, while ‘grief refers to the personal experience of the loss’. Grief is an emotional response of distress, pain and disorganisation. Mourning involves unravelling the previous bonds between the person and a deceased person (or object or part of the person). A process of mourning is needed to overcome grief.

Grief may be elicited by many different types of loss, such as a loss of self-esteem, loss of job, loss of financial status, loss of freedom, loss of physical abilities, loss of identity. Grief nearly always involves primary losses (death, job, relationship) and secondary losses or losses that result as a consequence of the primary loss (status, security, self-esteem). Secondary losses may not be apparent to the patient or client, and nurses can assist in the grieving process by helping the client to uncover these.

A number of key tasks of mourning have been described by Worden (2001) and these need to be accomplished if the client is to return to a state of stability. These are:

Grieving is a normal process after loss, and involves emotional (sadness, anger), physical (breathlessness, physical weakness) and cognitive (confusion, disbelief) sensations as well as behavioural changes (social withdrawal, crying). It can be helpful to let the client know that these are normal and that it is helpful to express and share these facets of grieving to promote healing. Remembering and talking about the lost loved one can help people to feel stronger, and Hedtke & Winslade (2004) argue that this type of narrative remembering practice has a healing and inspiring effect on those grieving.

Resources are now widely available to ensure that counsellors, professional carers and clients are better informed about issues surrounding death and dying. People with internet access can now study a wide range of information about death and dying, arguments for and against legislation on euthanasia, and information about cancer, suicide and AIDS. In addition, there is growing recognition of the need for communities to be aware of the diverse ways of grieving that different communities need to undergo and experience. NSW Health and Queensland Health have developed an online catalogue that outlines how different groups (professional and informal) in the community cope with bereavement, in an effort to provide culturally sensitive healthcare. Nurses working with culturally diverse client groups would be well advised to become familiar with some of these resources (see Ch 7).

Suicide and attempted suicide

People who are seriously depressed or who express feelings of worthlessness, guilt, anxiety and anger, and display severe agitation and irritability, may be at risk of suicide. It is important to note here, however, that ‘not all suicides or attempted suicides are by individuals with a clinical diagnosis of depression. Stressful and negative life events can become triggers for suicidal ideation and attempts, such as drug or alcohol abuse’ (Sharkey 1999b, p 92). Mann (2002) notes that alcohol and substance use increase the risk of suicide, as does the existence of a plan and a history of attempted suicide. Other illnesses too, such as schizophrenia or bipolar mood disorder, can be prominent. Suicide is often a complication of psychiatric illness but it is usually accompanied by additional risk factors such as a genetic link with someone who has committed suicide, living in rural areas with access to guns or other lethal means, poverty, unemployment and social isolation (Mann 2002). He also mentions the fact that some of the glossy media portrayals of suicide carry the risk of copycat suicides among young people.

The primary goal of crisis management is to reduce or eliminate the risk to the clients and/or to others (Doyle 1999), whether in a hospital or a community setting. Schulberg et al (2004) found that distressed people often visit primary care staff such as general practitioners in the weeks and months before a successful suicide. In a systematic review of suicide intervention strategies, Mann et al (2005) found that the education of physicians in recognising and treating depression, and removing or restricting access to lethal means, were the most effective interventions in preventing suicide. Professionals and lay people often explain suicide and attempted suicide differently, although there is a common perception that some form of crisis has occurred in the person’s life. Zadravec, Grad & Sočan et al (2006) emphasise the need for health carers to acquire a clear understanding of the beliefs of the suicidal person, which may be incorporated into the treatment and management plan.

A key role here for the nurse is to recognise the potential risk and intervene beforehand. Sharkey (1999b) extracted a number of high-risk indicators from the literature in this area. These are outlined in Box 10.2.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree