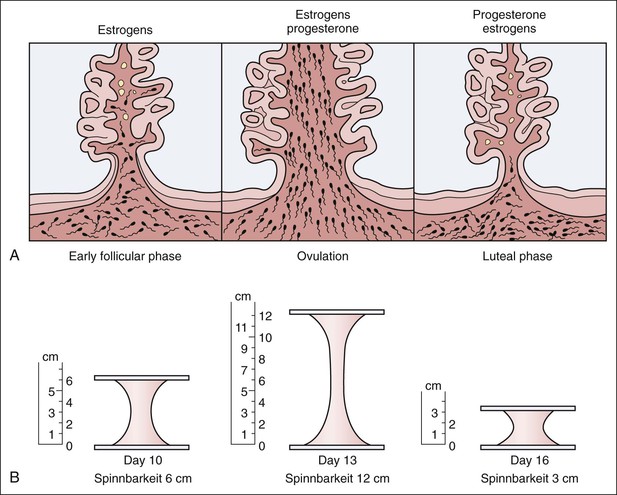

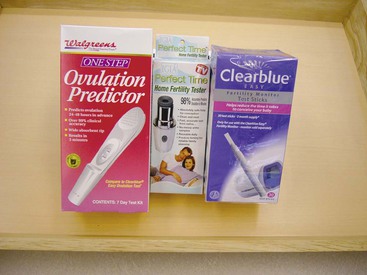

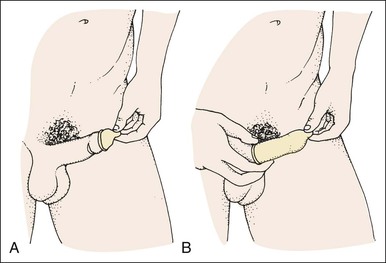

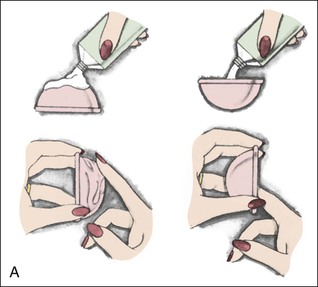

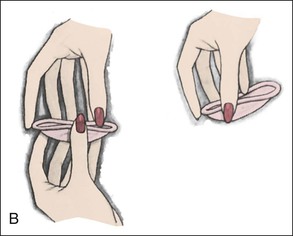

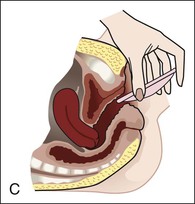

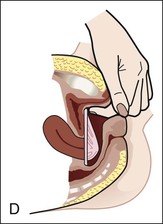

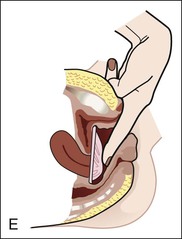

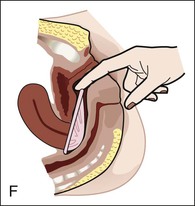

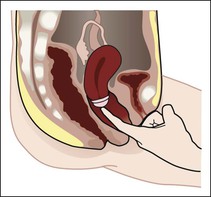

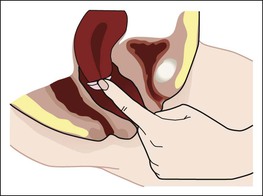

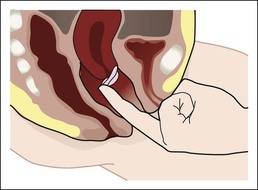

• Compare the various methods of contraception. • State the advantages and disadvantages of commonly used methods of contraception. • Explain the common nursing interventions that facilitate contraceptive use. • Recognize the various ethical, legal, cultural, and religious considerations of contraception. • Describe the techniques used for medical and surgical interruption of pregnancy. • Recognize the various ethical and legal considerations of elective abortion. • List the common causes of infertility. • Discuss the psychologic impact of infertility. • Identify common diagnoses and treatments for infertility. • Examine the various ethical and legal considerations of assisted reproductive therapies for infertility. Additional related content can be found on the companion website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Lowdermilk/Maternity/ • Critical Thinking Exercise: Patient Teaching: Contraception • Nursing Care Plan: Infertility • Nursing Care Plan: Sexual Activity/Contraception Family, friends, media, partner or partners, religious affiliation, and health care professionals all influence a woman’s perception of contraceptive choices. These external influences form a woman’s unique view. The nurse assists in supporting the woman’s decision based on the woman’s individual situation (see Nursing Process box: Contraception). Informed consent is a vital part in the education of the patient concerning contraception or sterilization. The nurse has the responsibility of documenting information provided and the understanding of that information by the patient. The acronym BRAIDED is often useful (see Legal Tip). To foster a safe environment for consultation, provide a private setting in which the woman can openly interact. Minimize any distractions, and have samples of birth control devices available for interactive teaching (Fig. 4-1). The ideal contraceptive is safe, easily available, economical, simple to use, and promptly reversible. Although no method may ever achieve all these objectives, significant advances in the development of new contraceptive technologies have occurred over the past 30 years (World Health Organization [WHO], 2004). The contraceptive failure rate refers to the percentage of contraceptive users expected to have an unintended pregnancy during the first year, even when they use a method consistently and correctly. Contraceptive effectiveness varies from couple to couple and depends on both the properties of the method and the characteristics of the user (WHO, 2004). Failure rates decrease over time, either because a user gains experience by using a method more appropriately or because those for whom a method is less effective stop using it. Coitus interruptus (withdrawal or “pulling out”) involves the male partner withdrawing the entire penis from the woman’s vagina and moving away from her external genitalia before he ejaculates. In theory, the spermatozoa are unlikely to reach the ovum to cause fertilization. Although the effectiveness of coitus interruptus depends mostly on the man’s disciplined capability to consistently ignore the powerful urge to continue thrusting, it has some concrete advantages over using no method. Adolescents and men with premature ejaculation often find this method difficult to use. This method is immediately available, costs nothing, and involves no hormonal alterations or chemicals. The effectiveness of this birth control technique is similar to that of barrier methods (Kowal, 2007). The percentage of women who will experience an unintended pregnancy within the first year of typical use (failure rate) of withdrawal is approximately 27% (Trussell, 2007). Some religions and cultures prohibit this technique. Coitus interruptus does not adequately protect against STIs or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. 1. Infertile phase: before ovulation 2. Fertile phase: approximately 5 to 7 days around the middle of the cycle, including several days before, during, and the day after ovulation Although ovulation is often unpredictable in many women, teaching the woman how to directly observe fertility patterns is empowering. FAMs consist of nearly a dozen categories. Each one uses a combination of charts, records, calculations, tools, observations, and either abstinence (natural family planning) or barrier methods of birth control during the fertile period in the menstrual cycle to prevent pregnancy (Jennings & Arevalo, 2007). Women can also use the charts and calculations associated with these methods to increase the likelihood of detecting the optimal timing of intercourse to achieve conception. FAMs have many advantages, including low to no cost, absence of chemicals and hormones, and lack of alteration in the menstrual flow pattern. However, some disadvantages to using FAMs exist. For some people, keeping strict records and attending time-consuming training sessions to learn about the method may be difficult. FAMs also decrease the spontaneity of coitus. In addition, external influences such as illness can alter a woman’s core body temperature and vaginal secretions. FAMs have decreased effectiveness in women with irregular cycles (particularly adolescents who have not established regular ovulatory patterns) (Jennings & Arevalo, 2007) (Box 4-1). FAMs do not protect against STIs or HIV infection. The typical failure rate for most FAMs is 25% during the first year of use (Trussell, 2007). Natural family planning (NFP) provides contraception by using methods that rely on avoidance of intercourse during fertile periods. NFP methods are the only contraceptive practices acceptable to the Roman Catholic Church. NFP methods combine charting signs and symptoms of the menstrual cycle with the use of abstinence during fertile periods. Signs and symptoms most commonly used are menstrual bleeding, cervical mucus, and basal body temperature (see later discussions) (Jennings & Arevalo, 2007). Practice of the calendar rhythm method is based on the number of days in each cycle counting from the first day of menses. With this method, the woman determines the fertile period after accurately recording the lengths of menstrual cycles for 6 months. The beginning of the fertile period is estimated by subtracting 18 days from the length of the shortest cycle. The end of the fertile period is determined by subtracting 11 days from the length of the longest cycle (Jennings & Arevalo, 2007). If the shortest cycle is 24 days and longest is 30 days, you apply the formula as follows: The Standard Days Method (SDM) is essentially a modified form of the calendar rhythm method that has a fixed number of days of fertility for each cycle—that is, days 8 to 19. The woman can purchase a CycleBeads necklace—a color-coded string of beads—as a concrete tool to track fertility (Fig. 4-2). Day 1 of the menstrual flow is the first day to begin the counting. Women who use this device avoid unprotected intercourse on days 8 to 19 (white beads on CycleBeads necklace). Although this method is useful to women whose cycles are 26 to 32 days long, it is unreliable to those who have longer or shorter cycles (CycleBeads, 2007). The typical failure rate for the SDM is 14% during the first year of use (Jennings & Arevalo, 2007). Based on monitoring and the recording of cervical secretions, the TwoDay Algorithm is used to identify the fertile window (Jennings & Arevalo, 2007). It appears to be simpler to teach, learn, and use than current natural methods. The woman needs to ask two questions each day: (1) “Did I note secretions today?” and (2) “Did I note secretions yesterday?” If the answer is yes to either question, she should avoid coitus or use a backup method of birth control. If the answer is no to both questions, her probability of getting pregnant is very low (Germano & Jennings, 2006). The cervical mucus ovulation-detection method (also called the Billings method and the Creighton model ovulation method) requires that the woman recognize and interpret the cyclic changes in the amount and consistency of cervical mucus that characterize her own unique pattern of changes (see Patient Instructions for Self-Management box). The cervical mucus that accompanies ovulation is necessary for viability and motility of sperm. It alters the pH environment, neutralizing the acidity, to be more compatible for sperm survival. Without adequate cervical mucus, coitus does not result in conception. Women check the quantity and character of mucus on the vulva or introitus with fingers or tissue paper each day for several months to learn the cycle. To ensure an accurate assessment of changes the cervical mucus should be free from semen, contraceptive gels or foams, and blood or discharge from vaginal infections for at least one full cycle. Other factors that create difficulty in identifying mucus changes include douches and vaginal deodorants, being in the sexually aroused state (which thins the mucus), and taking medications such as antihistamines (which dry up the mucus). Intercourse is considered safe without restriction beginning 4 days after the last day of wet, clear, slippery mucus (postovulation) (Jennings & Arevalo, 2007). The symptothermal method is a tool that the woman uses to gain fertility awareness as she tracks the physiologic and psychologic symptoms that mark the phases of her cycle. This method combines at least two methods, usually cervical mucus changes with basal body temperature (BBT), in addition to heightened awareness of secondary, cycle phase-related symptoms. Secondary symptoms include increased libido, midcycle spotting, mittelschmerz, pelvic fullness or tenderness, and vulvar fullness. The woman learns to palpate her cervix to assess for changes in texture, position, and dilation, which indicate ovulation. During the preovulatory and ovulatory periods the cervix softens, opens, rises in the vagina, and is more moist. During the postovulatory period the cervix drops, becomes firm, and closes. The woman notes the days on which coitus, changes in routine, illness, and so on have occurred (Fig. 4-3). Calendar calculations and cervical mucus changes help to estimate the onset of the fertile period, and changes in cervical mucus or the BBT help to estimate its end (see Patient Instructions for Self-Management: Assessing Basal Body Temperature). All of the preceding methods discussed estimate the occurrence and approximate timing of ovulation, but none of these methods can prove ovulation is occurring (Fig. 4-4). The urine predictor test for ovulation detects the sudden surge of luteinizing hormone (LH) that occurs approximately 12 to 24 hours before ovulation. Unlike BBT, illness, emotional upset, or physical activity do not affect the test. For home use, a test kit contains sufficient material for several days of testing during each cycle. An easy-to-read color change indicates a positive response or an LH surge. Directions for use of urine predictor test kits vary with the manufacturer. Saliva predictor tests for ovulation use dried, nonfoamy saliva as a tool to show fertility patterns. More research is needed to determine the efficacy of use of these tests for pregnancy prevention. An electronic hormonal fertility-monitoring device, the ClearBlue Early Fertility Monitor (CEFM), is a handheld device that uses test strips to measure urinary metabolites of estrogen and LH. The monitor provides the user with low, high, and peak fertility readings. The CEFM method incorporates the use of the monitor as an aid to learning NFP and fertility awareness. It continues to be investigated for its effectiveness in helping couples prevent pregnancy (Fehring, Schneider, Raviele, & Barron, 2007). Barrier contraceptives have gained in popularity not only as a contraceptive method, but also as a protective measure against the spread of STIs, such as human papillomavirus and herpes simplex virus (HSV). Some male condoms and female vaginal methods provide a physical barrier to several STIs, and some male condoms provide protection against HIV (Cates & Raymond, 2007; Warner, & Steiner, 2007). Spermicides serve as chemical barriers against the sperm. Spermicides work by reducing the sperm’s mobility; the chemicals attack the sperm flagella and body, thereby preventing the sperm from reaching the cervical os. Nonoxynol-9 (N-9), the most commonly used spermicidal chemical in the United States, is a surfactant that destroys the sperm cell membrane. However, data suggest that frequent use (more than two times a day) of N-9, or use as a lubricant during anal intercourse, may increase the transmission of HIV and can cause lesions (Cates & Raymond, 2007). Women with high risk behaviors that increase their likelihood of contracting HIV and other STIs need to avoid the use of spermicidal products containing N-9, including lubricated condoms, diaphragms, and cervical caps to which N-9 is added (WHO, 2004). Intravaginal spermicides are marketed and sold without a prescription as foams, tablets, suppositories, creams, films, and gels (Fig. 4-5). Preloaded, single-dose applicators small enough to be carried in a small purse are available. Effectiveness of spermicides depends on consistent and accurate use. Caution patients against misunderstanding terms: Contraceptive gel differs from fruit jelly, and cosmetics or hair products containing the nonspermicidal forms of nonoxynol are not adequate substitutes. The spermicide should be inserted high into the vagina so that it makes contact with the cervix. Some spermicides should be inserted at least 15 minutes before, but no longer than 1 hour before, sexual intercourse. Spermicide needs to be reapplied for each additional act of intercourse, even if using a barrier method. Studies have shown varying effectiveness rates for spermicidal use alone. The typical failure rate for spermicide use alone is 29% (Trussell, 2007). The male condom is a thin, stretchable sheath that covers the penis before genital, oral, or anal contact and is removed after the penis is withdrawn from the partner’s orifice after ejaculation (Fig. 4-6, A). Condoms are made of latex rubber, polyurethane (strong, thin plastic), or natural membranes (animal tissue). In addition to providing a physical barrier for sperm, nonspermicidal latex condoms also provide a barrier for STIs (particularly gonorrhea, chlamydia, and trichomoniasis) and HIV transmission. Condoms lubricated with N-9 are not recommended for preventing STIs or HIV (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006). Latex condoms will break down with oil-based lubricants and should be used only with water-based or silicone lubricants (Warner, & Steiner, 2007). Because of the growing number of people with latex allergies, condom manufacturers have begun using polyurethane, which is thinner and stronger than latex. Research is ongoing to determine the effectiveness of polyurethane condoms to protect against STIs and HIV. A functional difference in condom shape is the presence or absence of a sperm-reservoir tip (see Fig. 4-6, A). To enhance vaginal stimulation, some condoms are contoured and rippled or have ribbed or roughened surfaces. Thinner construction increases heat transmission and sensitivity; a variety of colors and flavors increases condoms’ acceptability and attractiveness (Trussell, 2007). A wet jelly or dry powder lubricates some condoms. Typical failure rate in the first year of male condom use is 15% (Trussell). To prevent unintended pregnancy and the spread of STIs, individuals must use condoms consistently and correctly. You can use instructions, such as those listed in Box 4-2, for patient teaching. The female condom is a lubricated vaginal sheath made of polyurethane and has flexible rings at both ends (see Fig. 4-6, A). The closed end of the pouch is inserted into the vagina and is anchored around the cervix, and the open ring covers the labia. Women whose partner will not wear a male condom can use this as a protective mechanical barrier. Rewetting drops or oil- or water-based lubricants help decrease the distracting noise that is produced while penile thrusting occurs. The female condom is available in one size, intended for single use only, and is sold over the counter. Individuals should not use male condoms with the female condom, because the friction from both sheaths can increase the likelihood of either or both tearing (Female Health Company, 2008). Typical failure rate in the first year of female condom use is 21% (Trussell, 2007). The contraceptive diaphragm is a shallow, dome-shaped latex or silicone device with a flexible rim that covers the cervix (see Fig. 4-6, A). Three types of diaphragms are available: coil spring, arcing spring, and wide seal rim. Available in many sizes, the diaphragm should be the largest size the woman can wear without her being aware of its presence. All diaphragms require a prescription, but over-the-counter products are being researched (Cates & Raymond, 2007). Typical failure rate of the diaphragm combined with spermicide is 16% in the first year of use (Trussell, 2007). Effectiveness of the diaphragm is less when used without spermicide (Trussell). Women at high risk for HIV should avoid use of N-9 spermicides with the diaphragm (Cates & Raymond). Inform the woman that she needs an annual gynecologic examination to assess the fit of the diaphragm. The woman should inspect the device before every use and replace it at least every 2 years. It will need to be refitted for a 20% weight fluctuation, after any abdominal or pelvic surgery, and after every term pregnancy and miscarriage or abortion that occurs after 14 weeks of gestation (Planned Parenthood, 2008). Because various types of diaphragms are on the market, use the package insert for teaching the woman how to use and care for the diaphragm (see Patient Instructions for Self-Management). Toxic shock syndrome (TSS), although reported in very small numbers, can occur in association with the use of the contraceptive diaphragm and cervical caps (Cates & Raymond, 2007). Instruct the woman about ways to reduce her risk for TSS. These measures include prompt removal of the diaphragm 6 to 8 hours after intercourse, not using the diaphragm or cervical caps during menses, and learning and watching for danger signs of TSS. Three types of cervical caps are available. Two types come in varying sizes and one type is one size fits all. They are made of rubber or latex-free silicone and have soft domes and firm brims (see Fig. 4-6, A). The cap fits snugly around the base of the cervix close to the junction of the cervix and vaginal fornices. The cap should remain in place no less than 6 hours and not more than 48 hours at a time. It is left in place at least 6 hours after the last act of intercourse. The seal provides a physical barrier to sperm; spermicide inside the cap adds a chemical barrier. The extended period of wear may be an added convenience for women. Instructions for the actual insertion and use of the cervical cap closely resemble the instructions for the use of the contraceptive diaphragm. However, the cervical cap can be inserted hours before sexual intercourse without a need for additional spermicide later, and no additional spermicide is required for repeated acts of intercourse when the cap is used. In addition, the cervical cap requires less spermicide than the diaphragm when initially inserted. The angle of the uterus, the vaginal muscle tone, and the shape of the cervix may interfere with the cervical cap’s ease of fitting and use. Correct fitting requires time, effort, and skill from both the woman and the clinician. The woman must check the cap’s position before and after each act of intercourse (see Patient Instructions for Self-Management box). The vaginal sponge is a small, round, polyurethane sponge that contains N-9 spermicide (see Fig. 4-6, B). It is designed to fit over the cervix (one size fits all). The side that is placed next to the cervix is concave for better fit. The opposite side has a woven polyester loop to be used for removal of the sponge. The woman moistens the sponge with water before insertion. It provides protection for up to 24 hours and for repeated instances of sexual intercourse. The sponge should be left in place for at least 6 hours after the last act of intercourse. Wearing longer than 24 to 30 hours may put the woman at risk for TSS (Cates & Raymond, 2007). Failure rates for these barriers in the first year of use are 16% in nulliparas and 32% in multiparous women (Trussell, 2007). More than 70 different contraceptive formulations are available in the United States today. Table 4-1 describes the general classes. Because of the wide variety of preparations available, the woman and nurse must read the package insert for information about specific products prescribed. Formulations include combined estrogen-progestin medications and progestational agents. The formulations are administered orally, transdermally, vaginally, by implantation, by injection, or via the intrauterine route. TABLE 4-1 Combined steroids induce other contraceptive effects. These substances alter maturation of the endometrium, making it a less favorable site for implantation. COCs also have a direct effect on the endometrium such that from 1 to 4 days after the last COC is taken the endometrium sloughs and bleeds as a result of hormone withdrawal. The withdrawal bleeding is usually less profuse than that of normal menstruation and may last only 2 to 3 days. Some women have no bleeding at all. The cervical mucus remains thick from the effect of the progestin (Nelson, 2007). Monophasic pills provide fixed doses of estrogen and progestin. Multiphasic pills (e.g., biphasic and triphasic oral contraceptives) alter the amount of progestin and sometimes the amount of estrogen within each cycle. These preparations reduce the total dose of hormones in a single cycle without sacrificing contraceptive efficacy (Nelson, 2007). To maintain adequate hormonal levels for contraception and enhance compliance, women should take COCs at the same time each day. Evidence of noncontraceptive benefits of oral contraceptives is based on studies of high-dose pills (50 mg of estrogen). Few data exist on noncontraceptive benefits of low-dose oral contraceptives (less than 35 mg of estrogen) (Nelson, 2007). The noncontraceptive health benefits of COCs include decreased menstrual blood loss and decreased iron-deficiency anemia, regulation of menorrhagia and irregular cycles, and reduced incidence of dysmenorrhea and premenstrual syndrome (PMS). Oral contraceptives also offer protection against endometrial cancer and ovarian cancer, reduce the incidence of benign breast disease, and improve acne. They also protect against the development of functional ovarian cysts and salpingitis and decrease the risk of ectopic pregnancy. Oral contraceptives are considered a safe option for nonsmoking women until menopause. Perimenopausal women can benefit from regular bleeding cycles, a regular hormonal pattern, and the noncontraceptive health benefits of oral contraceptives (Nelson). Oral hormonal contraceptives are initiated in three ways: (1) quick start—taking the first pill the same day as the clinic appointment and using a back-up method for 7 days, (2) first day start—taking the first pill on the first day of the menstrual cycle (menses), and (3) Sunday start—taking the first pill on the first Sunday after the start of their menstrual period (Nelson, 2007). Taken exactly as directed, COCs prevent ovulation, and pregnancy cannot occur; the overall effectiveness rate is almost 100%. Almost all failures (i.e., occurrence of pregnancy) are caused by omission of one or more pills during the regimen. The typical failure rate of COCs resulting from omission is 8% (Trussell, 2007). COCs also can be taken using different patterns. Most are taken on a monthly cycle of 3 weeks of active pills followed by seven placebo pills. Some regimens now come with fewer placebo pills and more active pills, although research is still needed on the efficacy and safety of these regimens. Another pattern of use is the extended cycle—taking pills for longer times, which lessens the frequency of menstrual periods (i.e., withdrawal bleeding). The extended period can be short, such as for a special event like a vacation or honeymoon, or for more extended times. For example, a woman can take 2 months of active pills followed by seven placebo pills at the end of the second package or take a U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved extended-use pill. One such pill is levonorgestrel–ethinyl estradiol (Seasonale) that contains both estrogen and progestin, taken in 3-month cycles of 12 weeks of active pills followed by 1 week of inactive pills. Menstrual periods occur during the thirteenth week of the cycle. This active pill provides no protection from STIs, and risks are similar to those of COCs. Available only by prescription, women must take Seasonale on a daily schedule, regardless of the frequency of intercourse. Because users will have fewer menstrual flows, they should consider the possibility of pregnancy if they do not experience their thirteenth-week flow. Typical failure rate in the first year of Seasonale use is less than 5% (U.S. FDA, 2009). Disadvantages and side effects. You need to screen women for medical conditions that preclude the use of oral contraceptives. Contraindications for COC use include a history or presence of thromboembolic disorders, cerebrovascular or coronary artery disease, valvular heart disease, breast cancer or other estrogen-dependent tumors, impaired liver function, and liver tumor. Women older than 35 years of age who smoke (more than 15 cigarettes per day), or those with severe hypertension or who have headaches with focal neurologic symptoms should not use COCs. Surgery with prolonged immobilization or any surgery on the legs and diabetes mellitus (of more than 20 years’ duration) with vascular disease also contraindicate COC use (Nelson, 2007). Certain side effects of COCs are attributable to estrogen, progestin, or both. Serious adverse effects documented with high doses of estrogen and progesterone include stroke, myocardial infarction, thromboembolism, hypertension, gallbladder disease, and liver tumors. Common side effects of estrogen excess include nausea, breast tenderness, fluid retention, and chloasma. Side effects of estrogen deficiency include early spotting (days 1 to 14), hypomenorrhea, nervousness, and atrophic vaginitis leading to painful intercourse (dyspareunia). Side effects of progestin excess include increased appetite, tiredness, depression, breast tenderness, vaginal yeast infection, oily skin and scalp, hirsutism, and postpill amenorrhea. Side effects of progestin deficiency include late spotting and breakthrough bleeding (days 15 to 21), heavy flow with clots, and decreased breast size. One of the most common side effects of combined COCs is bleeding irregularities (Nelson, 2007). In the presence of side effects, especially those that are bothersome to the woman, a different product, different drug content, or another method of contraception may be required. The “right” product for a woman contains the lowest dose of hormones that prevents ovulation and that has the fewest and least harmful side effects. Predicting the right dose for any particular woman is impossible. Issues to consider in prescribing oral contraceptives include history of oral contraceptive use, side effects during past use, menstrual history, and drug interactions (Nelson, 2007). The following medications, when taken simultaneously with oral contraceptives, can reduce the effectiveness of contraceptives (Nelson, 2007).

Contraception, Abortion, and Infertility

Web Resources

![]()

Care Management

Methods of Contraception

Coitus interruptus

Fertility awareness methods

Calendar rhythm method.

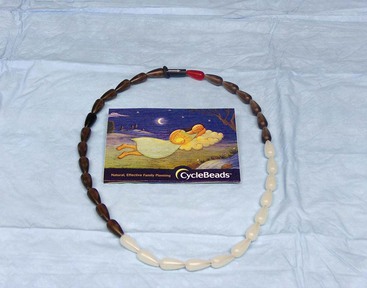

Standard days method.

TwoDay method of family planning.

Ovulation method.

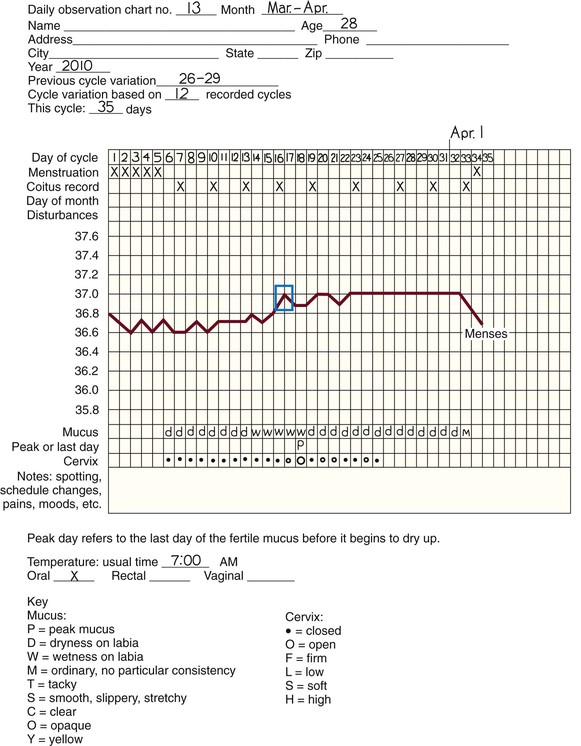

Symptothermal method.

Home predictor test kits for ovulation.

Barrier methods

Spermicides.

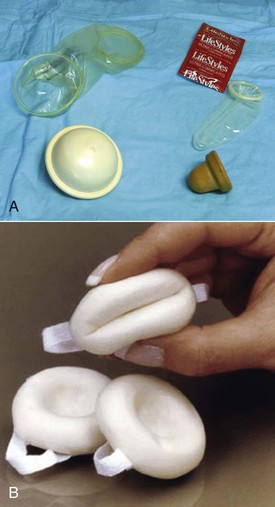

Condoms.

Diaphragms, cervical caps, and sponges.

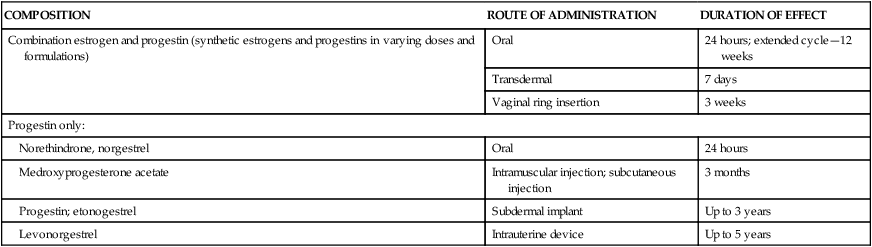

Hormonal methods

COMPOSITION

ROUTE OF ADMINISTRATION

DURATION OF EFFECT

Combination estrogen and progestin (synthetic estrogens and progestins in varying doses and formulations)

Oral

24 hours; extended cycle—12 weeks

Transdermal

7 days

Vaginal ring insertion

3 weeks

Progestin only:

Norethindrone, norgestrel

Oral

24 hours

Medroxyprogesterone acetate

Intramuscular injection; subcutaneous injection

3 months

Progestin; etonogestrel

Subdermal implant

Up to 3 years

Levonorgestrel

Intrauterine device

Up to 5 years

Combined estrogen-progestin contraceptives

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Contraception, Abortion, and Infertility

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access