INTRODUCTION

People have the right to be continent whenever that is achievable. When true continence is not achievable, people have the right to the highest standards of continence care and incontinence management.

Urinary incontinence is a worldwide problem. A prevalence of 32% was found in the UK and over 30% in four European countries (Hunskar et al 2002). Good Practice in Continence Services (Department of Health 2000) suggests that urinary incontinence may, in the general population, be as high as 1 in 10 to 1 in 5 women over 65 years and 1 in 14 to 1 in 10 males over 65 years, and this may rise to 1 in 2 in homes caring for the infirm elderly. The Children’s NSF (Department of Health 2004 section 10:17, p. 32) states ‘there are at least 500,000 children who suffer from nocturnal enuresis and a significant number with daytime wetting and faecal incontinence’.

The presence of symptoms of leaking urine have an impact on the quality of life and pyschological well-being of an individual (Shaw 2001), and bowel problems remain a taboo topic in western societies (Norton 2005). However, incontinence is a treatable condition, where provision of appropriate physiological and psychological intervention can help a client achieve continence. Education of the general public to dispel negative and misguided attitudes is of prime importance.

This chapter aims to explain the reasons elimination problems occur and to introduce you to the knowledge and skills you will need to assess clients with continence difficulties and to plan their care. It also discusses the impact of national policies to ensure this care is of a high standard.

OVERVIEW

Subject knowledge

This section covers the normal anatomy and physiology of micturition and defaecation, how continence is gained, and then describes how alterations from the normal can give rise to incontinence. It explores how continence is affected when ability to cope with activities of daily living change, and examines how society and its attitudes can affect elimination behaviour.

Care delivery knowledge

This section outlines the skills needed to assess clients’ problems, ways of promoting continence, how to manage incontinence and additional treatments that can be offered by referring clients to the continence advisor and the multidisciplinary team.

Professional and ethical knowledge

Policy issues around promoting and managing continence are highlighted. The responsibilities of the continence advisor, the nurse and the multidisciplinary team, and the vision for integrated services are outlined. Educational needs and ethical issues of continence care are discussed.

Personal and reflective knowledge

The aim of the exercises is to help you use the knowledge gained and develop them for your portfolio.

On pages 434–435 there are four case studies, each one relating to one of the branch programmes. You may find it helpful to read one of them before you start the chapter and use it as a focus for your reflections while reading as part of your portfolio development.

SUBJECT KNOWLEDGE

BIOLOGICAL

Continence is a skill gained when a person learns to recognize the need to pass urine and/or bowel motion, has the ability to reach an acceptable place to void, is able to hold on until they reach there and is able to void/eliminate effectively on reaching that place (Getliffe & Dolman 2007).

The first section examines the physiological mechanism used to achieve continence and then how it may fail and cause urinary and faecal incontinence. Other types of physiological failures that can cause problems with elimination are also considered.

ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE LOWER URINARY TRACT

The urinary system consists of two kidneys, two ureters, a bladder and a urethra. Urine is made in the kidneys when the blood is filtrated to remove waste products and keep water and electrolytes balanced in the body. Antidiuretic hormone (ADH) will decrease urine production, and will normally rise at night to decrease the amount of urine produced. Urine passes down the ureters from the kidneys. It is important that it does not reflux back to the kidneys, causing renal damage. This is prevented by; the angle at which the ureters enter the bladder; peristalsis in the ureters causing urine to flow towards the bladder; and the narrowing along the ureter.

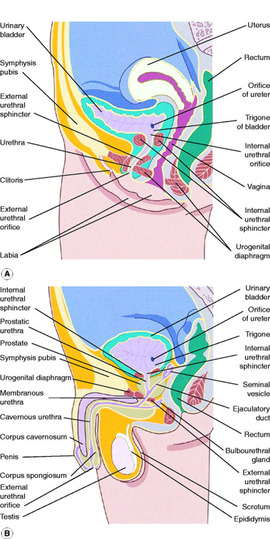

To understand continence fully it is important to know about the organs involved in storage and evacuation (bladder and urethra) and how they relate to the lower bowel and the male and female reproductive organs (Fig. 18.1).

|

| Figure 18.1 |

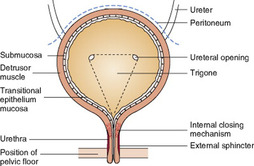

The bladder is made of four layers of tissue:

• an inner layer of transitional epithelium

• a connective tissue layer

• smooth muscle

• an outer coating covering the upper surface, the peritoneum (Fig. 18.2).

|

| Figure 18.2 (after Cheater 1992b). |

The epithelial layer has the ability to stretch and it also produces mucus to protect the tissues from the acidity of the urine. The smooth muscle is known as the detrusor muscle and is made up of layers of longitudinal and circular muscle to allow it to both stretch and contract. Stretch receptors monitor the fullness of the bladder and are found throughout this muscle, but are concentrated in the sensitive trigone, a triangular area between the ureters and the urethra. Urine enters the bladder through the ureters and leaves through the urethra (see Fig. 18.2) (Getliffe & Dolman 2007).

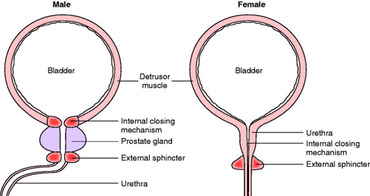

The urethra is a tube running from the bladder and is 3–5 cm long in the female and 18–22 cm long in the male. It has a thick mucosal lining containing mucus-producing cells, and is folded to enhance the watertight seal of the bladder. At the bladder neck the smooth muscle passes from the bladder to the urethra, forming the internal closing mechanism. This is more distinct in men than women, being found just above the prostate gland (Fig. 18.3). (Getliffe & Dolman 2007).

|

| Figure 18.3 |

The external sphincter is made of voluntary muscle and in men it is a separate ring just below the prostate gland. This allows the sphincters to work independently so during ejaculation the bladder is closed but the urethra can be open. In women the internal closing mechanism is less distinct and the external sphincter surrounds this. It is also sensitive to oestrogen levels. These factors may give rise to an incompetent sphincter (discussed later in the chapter).

The pelvic floor is a muscular sling supporting the abdominal organs. It is pierced by the rectum posteriorly and the vagina and urethra anteriorly. It is very important in continence, contracting to maintain urinary and faecal continence, but relaxing to allow expulsion of urine and faeces (Emmanuel 2004). The bladder and the proximal urethra sit well supported above the pelvic floor, a position needed to maintain continence (see Fig. 18.2).

The coordination of bladder emptying is controlled by nerve pathways. Damage to these pathways can upset their balance and cause incontinence.

• How will damage in the following areas affect the micturition process?

– the frontal lobe of the brain

– the midbrain or pons

– the cervical spine

– the lumbar spine

– the sacrum

– the nerves forming the spinal reflex arc.

• Compare your answers with the problems described in the following discussion of altered physiology.

• As you gain nursing experience, list the conditions caused by damage to the central nervous system or spinal cord and look at the patient’s subsequent continence.

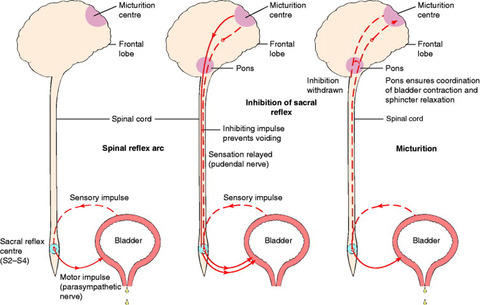

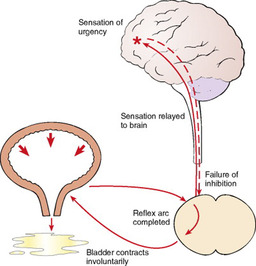

The bladder is controlled by both the somatic and the autonomic nervous system, which allows it to store urine and expel it at a suitable time. The parasympathetic system innervates the detrusor muscle of the bladder, allowing the bladder to relax during its filling phase while the sphincters remain closed. It allows filling up to approximately 300 mL without registering changes of pressure. This is known as compliance. Once this volume is reached the sensory parasympathetic nerves transmit impulses to the sacral area of the spinal cord (S2–S4). A spinal reflex arc is completed allowing impulses to pass back to the bladder through the parasympathetic motor nerves, causing the muscle to contract and the sphincter to open, resulting in micturition (Fig. 18.4).

The voluntary control works in an inhibitory manner: sensory impulses are sent through the pudendal nerve to the cortical micturition centre in the frontal lobe of the brain saying bladder is full. Inhibitory impulses are passed back to the sacrum to prevent the sacral reflex arc initiating micturition. When the individual is ready to pass urine, the inhibition is lifted (see Fig. 18.4). These voluntary nerve pathways pass through the pons in the brainstem and it is thought that this area ensures that the sphincters’ opening and the bladder’s contraction are coordinated (Fader & Craggs 2003). The reflex arc action occurs in babies, and the inhibitory process begins to develop in infants from the age of 18 months as the central nervous system matures.

ALTERED PHYSIOLOGY OF THE LOWER URINARY TRACT

The conditions will be discussed separately so that you can understand the different symptoms of each type. This is important when you assess patients as some clients may have more than one condition causing their continence difficulties.

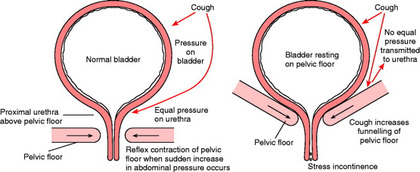

Stress incontinence

Stress incontinence is more common than diabetes or asthma (Bishop 2005). It is defined as an involuntary loss of urine during increase in intra-abdominal pressure caused by laughing, sneezing or lifting. It occurs during the filling phase of the bladder causing leakage of urine. When the bladder is held in the correct position by the pelvic floor the inner closing mechanism and the external sphincter of the bladder prevent leakage (Fig. 18.5). If the pelvic floor is weak the bladder prolapses downwards and there is no compensatory pressure helping to counteract the pressure on the bladder and leakage may occur (see Fig. 18.5); this is made worse if the urethral closing mechanism is also weak, for example when oestrogen levels are low (Dolman 2007). Table 18.1 lists the common causes of stress incontinence.

| Mechanism | Cause | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Weakness of pelvic floor muscles (due to muscle or nerve damage) | Pregnancy | Eason et al(2004) |

| Childbirth | ||

| Trauma during childbirth (vaginal delivery) | ||

| Forceps delivery | Klein et al (1997) | |

| Obesity | ||

| Increased abdominal pressure | Chronic cough Prolonged lifting of heavy weights Childbirth | |

| Oestrogen deficiency (oestrogen receptors are found in pelvic floor, bladder and bladder neck, thus there is good muscle tone in the presence of oestrogen) | Pregnancy Last part of menstrual cycle Menopause | Dolman (2007) |

Overactive bladder

Overactive bladder is characterized by involuntary bladder contractions during its filling phase and produces symptoms of urgency, frequency, urge incontinence, nocturia and nocturnal enuresis (see Table 18.2 for definitions of terms) (Wein et al 2002). The inhibition impulse from the cortical micturition centre of the cortex is not sufficient to prevent the sacral reflex action occurring, so the bladder starts to contract and voiding begins. This may be due to damage to the central nervous system, for example a cerebrovascular accident (stroke), tumours, spinal cord injuries or malfunction of the conduction of the nerve impulses, as seen in multiple sclerosis (MS) and Parkinsonism. Local bladder factors may be responsible for causing spasm that overrides cortical inhibition, for example caffeine (Bryant et al 2002), urinary tract infections, concentrated urine or external factors such as prostatic enlargement or constipation. Overactive bladder may occur in the absence of any detectable pathology (Fig. 18.6) (Getliffe & Dolman 2007).

| Urgency | The need to pass urine in a great hurry |

| Sensory urgency | Urgency in the absence of unstable bladder contractions; the bladder is hypersensitive |

| Frequency | Visiting the toilet to pass urine more often than is acceptable to the patient; this usually means more than seven times during the day and more than once at night |

| Urge incontinence | While experiencing urgency the patient may not be able to get to the toilet in time and is therefore incontinent |

| Reflex incontinence | Urine loss due to detrusor hyperreflexia (or involuntary urethral relaxation) when there is aneuropathic absence of sensation |

| Hesitancy | Difficulty in initiating voiding |

| Dribbling | Dribbling of urine after voiding, due to pooling of urine in the urethra between internal and external sphincter |

| Nocturnal enuresis | Bed-wetting while asleep |

| Passive incontinence | Wetting at rest without any coincident activity or sensation |

| Dysuria | Pain or burning while actually passing urine |

| Haematuria | Blood in the urine |

|

| Figure 18.6 (reproduced with kind permission of Coloplast Ltd). |

Voiding difficulties

There are two reasons for voiding difficulties and each is described in the following section.

Bladder outflow obstruction

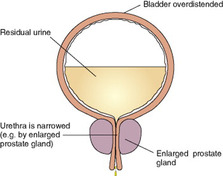

This condition can occur when the outlet to the bladder becomes obstructed (Fig 18.7). The most common cause in males is prostatic enlargement. It is estimated that approximately 2.5 million men in the UK may have symptoms of this type of obstruction (Brown & Das 2002). The condition may also occur in both males and females with urethral narrowing or stricture, and more rarely with urethral cancers and stones.

|

| Figure 18.7 (reproduced with kind permission of Coloplast Ltd). |

Symptoms of this problem could include bladder filling problems, such as frequency and urgency of micturition, and bladder voiding symptoms, such as hesitancy, poor stream and varying degrees of retention of urine. Urinary tract infection and longer term damage to the upper renal tract and detrusor muscle of the bladder may occur.

Detrusor hypoactivity (atonic bladder)

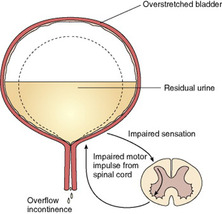

In some cases, if the detrusor muscle of the bladder fails to contract fully it will not completely empty and the bladder will retain urine (Fig 18.8). To some degree, these symptoms may mimic those of outflow obstruction, such as repeated urinary tract infection. Where bladder sensation is present, the patient will know their bladder is not empty and experience frequency and urgency of micturition.

|

| Figure 18.8 (reproduced with kind permission of Coloplast Ltd). |

The causes of this condition may be due to muscle weakness seen more commonly in elderly clients (Norton 2005). They include underlying neuropathy such as stroke (Brittain et al 1998) and peripheral neuropathy in diabetes. Spinal cord damage may also be a contributory factor either as a result of trauma or disease. Approximately 1 in 10 patients suffering with multiple sclerosis exhibit this type of voiding dysfunction (Kobashi & Leach 1999). Also clients with multiple sclerosis or stroke may experience a condition termed detrusor sphincter dyssynergia. Here the detrusor muscle does contract but the sphincter fails to relax leading to a non-emptying bladder.

If the nervous control is completely damaged, as seen in some children with spina bifida, the bladder cannot empty at all and this is known as atonic bladder.

Influences on bladder function

There are other influences on the normal functioning bladder that may cause incontinence: these are fluid intake, urinary tract infection, drugs and constipation. The last two will be discussed later.

Many clients will cut down their fluid intake mistakenly believing it will reduce their incontinence. Concentrated urine will encourage bladder spasm and thus cause urgency and frequency (Getliff & Dolman 2007). This problem is also found in young children especially when starting school, unless encouraged to drink. They may drink minimal amounts, which may cause some girls to exhibit daytime wetting and may also be a factor in children who wet the bed (Butler et al 2005). The opposite problem sometimes occur in clients with learning disabilities who drink excessive amounts of water and produce large volumes of urine, causing frequency. Urinary tract infection will also cause bladder spasm giving urgency and frequency and may exacerbate urinary problems.

Wein et al (2002), reviewing the literature on nocturia, found that it increases with age and that less than 1 in 5 people over 80 years have no reported symptoms. They identified three areas that may cause this problem. Firstly, storage problems due to decreased bladder capacity, bladder overactivity and the effects of reduced oestrogen levels. Secondly, polyuria, either at night because of daytime fluid retention, venous insufficiency, hypoalbuminaemia, diuretic therapy, and congested heart failure or throughout the day due to disease, e.g. diabetes mellitus, diabetes insipidus. And finally, sleep related issues such as sleep disturbance, sleep apnoea and length of time in bed can also be a cause.

ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE LOWER BOWEL

‘Faecal incontinence is the most embarrassing, socially unacceptable and demoralizing of symptoms’ (Irvine 1996: 226). Looking after a person with faecal incontinence is poorly tolerated by carers and frequently leads to the discontinuation of community care. Faecal incontinence is not as widespread as urinary incontinence. The Department of Health (2000) estimates a prevalence of faecal incontinence of 1% among total population of adults, rising to 17% in the very elderly.

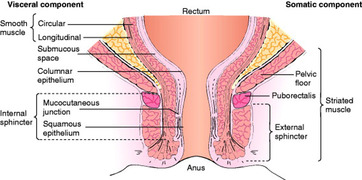

The large intestine consists of the caecum and colon and terminates with the rectum and anal canal. It receives 600 mL of chyme from the small intestine daily and reduces it to 150–200 mL of faeces by reabsorbing water from the chyme as it travels through the colon. Faeces are stored in the rectum and eliminated though the anal canal (Norton & Chelvanayagam 2004). The rectum has a mucosal lining (i.e. columnar epithelial), which produces mucus to lubricate the passage of stool. The anal canal has a squamous epithelial lining, which is dry and very sensitive and can distinguish between flatus and stool, allowing flatulence to escape to relieve gaseous distension, but retaining faeces. The muscle layer of the rectum is smooth involuntary muscle and contains specialized stretch receptors, which monitor the fullness of the rectum. In the anal canal the smooth involuntary muscle thickens to form the internal sphincter, which is surrounded by a layer of voluntary muscle, the anal sphincter (Fig. 18.9) (Emmanuel 2004). Vascular projections (anal cushions) are found in the anus; these help to reduce feacal leaking and may give rise to haemorrhoids (Barrett 2002).

|

| Figure 18.9 (from Bendall 1989). |

Faeces formed by the large bowel enter the rectum by a series of peristaltic movements known as the gastrocolic reflex, which is stimulated by physical activity and ingestion of food (Emmanuel 2004). Once 150 mL or more of stool is in the rectum, the individual gets a feeling of fullness and impending defaecation and the internal anal sphincter relaxes and allows the stool to enter the anal canal. If defaecation is not convenient, the external sphincter remains closed and the faeces return to the rectum (Edwards et al 2003). However, if it is appropriate, the external sphincter relaxes and defaecation occurs. This is most efficiently achieved in a squatting position as pressure from the abdominal muscles will cause the external and internal anal sphincters to relax, the pelvic floor will drop down to form a funnel, and the bowel will empty easily (Horton 2004).

The nervous control is a reflex action involving the myenteric plexus and stimulated by a full rectum. The internal anal sphincter is controlled by the autonomic nervous system and the external sphincter is controlled by the somatic nervous system (pudendal nerve).

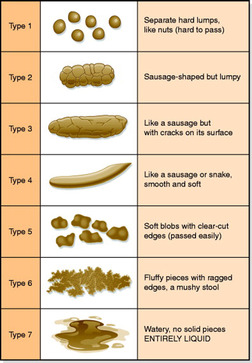

If the defaecation mechanism is working properly the individual should be able to pass 150–200 mL of formed but soft stool regularly. However, the frequency of defaecation varies between individuals, ranging from three times a day to once in three days (Emmanuel 2004). The consistency of the stool may show individual differences; these can be assessed using the Bristol Stool Scale, 3 and 4 on this scale being considered to be preferable (Fig. 18.10).

|

| Figure 18.10 (reproduced with kind permission of Norgine Ltd). |

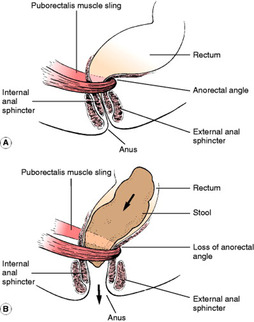

The pelvic floor is responsible for keeping the rectum in the correct position. The muscle of the pelvic floor, which anchors the rectum to the pubis (i.e. the puborectalis), is of great importance in maintaining faecal continence. The puborectalis maintains an angle of 60–105 ° between the rectum and the anal canal. This angle acts as a flap valve, which closes when abdominal pressures rise, for example due to sneezing or lifting, preventing leakage through the canal (Fig. 18.11). During defaecation the pelvic floor relaxes increasing this angle allowing easy passing of stool (see Fig. 18.11). The nerve supply of the pelvic floor is innervated by the same nerve as the external sphincter, the pudendal nerve. This nerve synapses with the autonomic system at S2–S4 (Edwards et al 2003).

|

| Figure 18.11 |

ALTERED PHYSIOLOGY OF THE LOWER BOWEL

Faecal incontinence is defined as involuntary and/or inappropriate passing of liquid or solid stool. Norton & Chelvanayagam (2004) classify the causes of faecal incontinence under the following headings:

• anal sphincter or pelvic floor damage

• gut motility/stool consistency

• anorectal pathology (e.g. haemorrhoids, anal fistula, rectal prolapse)

• neurological disease

• secondary to degenerative neurological disease

• impaction with overflow

• lifestyle (discussed in management of constipation).

Anal sphincter or pelvic floor damage and/or anorectal pathology

Faecal incontinence may occur when abdominal pressure increases for example when sneezing or lifting (see Fig. 18.11). It may be due to the following: damage of the anal sphincters, the pudendal nerve, weakness of the pelvic floor, (the puborectalis muscle) and increase of the anorectal angle (Norton & Chelvanayagam 2004). Damage to the internal or external anal sphincters (or both) due to forceps delivery or perineal tears during childbirth are often responsible for faecal incontinence in younger women (Porrett 2006). If the external sphincter is damaged, women may experience urgency, while damage to the internal sphincter may cause faecal seeping. Reduced muscle tone and nerve degeneration cause anorectal abnormality (Harari 2004).

Gut motility/stool consistency

A bad attack of diarrhoea may cause faecal incontinence, especially in those who are very ill, bed bound or have mobility problems. This may be due to infection or gastro-intestinal disease. Severe and prolonged attacks of diarrhoea should have a medical referral as should rectal bleeding (Norton & Chelvanayagam 2004).

Neurological causes

Neurogenic bowel refers to constipation or faecal incontinence that occurs in patients with major neurological disease or injury, for example stroke or multiple sclerosis (Wiesel & Bell 2004). Spinal cord injury also leads to bowel dysfunction of varying types depending on the level and the degree of neurological completeness of the lesion (Ash 2005). The differences in the areas and seriousness of the neurological damage mean that management of this group must be individualized as there is a fine line between relieving constipation and causing faecal incontinence.

Secondary to degenerative neurological disease

Elderly patients with dementia may be faecally incontinent due to decreased intellectual function, loss of social awareness and neurological sensation and an inability to control their bowels (Norton & Chelvanayagam 2004).

Faecal impaction

Constipation affects up to 27% of the population of the Western world (Lembo & Camilleri 2003). Faecal impaction can be the result of chronic constipation (Table 18.3) and may give rise to faecal incontinence of either solid or liquid stool (Norton & Chelvanayagam 2004). The latter is seepage from above the obstruction, and slime as a result of bacterial breaking down hard faeces and extra mucus. It is foul smelling and known as spurious diarrhoea. Thompson et al (1999) defined constipation as demonstrating two of the following symptoms: straining at stool; lumpy hard stools; sensation of incomplete emptying; and fewer than two bowel movements a week (ROME II criteria).

| Mechanism | Causes |

|---|---|

| Insufficient material in the bowel | Lack of fibre in the diet Poor fluid intake |

| Abnormal neurological control | Spinal or nerve injury affecting autonomic nervous system Hirschsprung disease (a condition where there is an absence of nerves in the wall of bowel) Psychological factors, by an inhibitory effect on autonomic innervation (Dykes et al 2001) |

| Obstruction | Tumours Diverticular disease Haemorrhoids Congenital abnormalities |

| Pregnancy | High progesterone levels causing decrease in motility of the gastrointestinal tract |

| Metabolic causes | Diabetes mellitus Hypothyroidism Dehydration |

| Drugs | Aluminium (antacids) Anticholinergics Diuretics Iron Analgesia opiates Verapamil |

| Laxative abuse | Overuse of laxatives can cause damage to the nerves in the colon, resulting in atonic bowel |

| Environmental | Anything preventing defaecation, e.g. lack of privacy, dirty toilets, insufficient toilets |

| Immobility | Lack of exercise means the bowel itself is less active. The client may have difficulty reaching the toilet |

Faecal impaction may not always be due to large amounts of small hard stool but large amounts of soft faeces, when the client may be unable to completely empty from their bowel despite regular bowel movement. This can also cause faecal incontinence. The term ‘faecal loading’ may be the best term for this type of bowel problem (Barrett 2002). Impaction is often found in the frail elderly who may have impaired rectal sensation and thus do not initiate defaecation effectively (Harari 2002).

GENERAL ALTERED PHYSIOLOGY CAUSING CONTINENCE PROBLEMS

Returning to the original definition of continence, we can see that physiological changes in other systems of the body can affect the continence state of the client. For example when identifying the place for elimination the client needs to be orientated. Clients with dementia, confusion or disorientation may become incontinent simply because they are unable to locate the toilet (Eustice 2007). Finding the correct receptacle may also be a problem: the demented patient may confuse washbasins with urinals. To locate a toilet, a person needs to be able to follow a signed route, which can be difficult in dim corridors or if the person is blind or partially sighted. The sign also needs to be recognizable, because notices in small print or the modern stylized pictures may not be obvious to the disorientated. A sign only saying ‘toilets’ is also unsuitable, causing discomfort to people who fear sharing facilities with the opposite sex. People may have to ask for the toilet, which can be embarrassing for some, but very difficult for clients with communication problems due to physical illness (e.g. stroke) or mental illness (e.g. depression).

The ability to reach the toilet is essential and clients with problems like stiff joints or poor balance can find this difficult. In addition this effort may tire them, resulting in an incontinent episode before they reach the toilet. Obstacles en route such as stairs, narrow passages, sharp corners, loose mats and heavy doors can also hamper the journey. Memory loss causes problems as the client may forget what their goal is after setting out to go to the toilet and wander around until it is too late (Stokes 2002). On reaching the toilet itself the client needs dexterity to remove clothing before eliminating; inappropriate clothing may slow the client so much that they may begin to void or defaecate too soon. To complete the toileting sequence a person must be able to squat, or for men have the stability to stand to urinate, and this may cause problems for the disabled. This type of incontinence is often known as functional incontinence (see Evolve 18.1).

Ageing

Any of the general physiological factors discussed above can be a problem for the elderly, but they are not inevitable. The ageing process may affect continence in many other ways and the following factors should be considered

• Circulatory changes and kidney deterioration mean that urine production is less efficient; this results in larger amounts of urine being produced during the night – 35% of the 24-hour volume as opposed to 20% in younger adults (Weiss & Blaivas 2000).

• Hormonal change in the amount of oestrogen circulating in a woman’s body decreases. As a result, the soft convoluted tissue of the vagina and urethra become less elastic with less pronounced folds, resulting in the loss of the watertight seal in the urethra. This deficiency also causes the pelvic floor muscle tone to become lax, and may lead to stress incontinence (Cardosa et al 2000).

• The elderly man has a tendency towards prostatic enlargement and therefore overflow incontinence.

• There is a deterioration of detrusor contractility (Pfisterer et al 2006). The bladder may not empty completely so that a residual volume builds up in the bladder.

• Deterioration of nerves occurs so that the sensation of bladder fullness becomes less acute, and the older person will feel the urge to urinate when the bladder is 90% full, and not 50%, as in the younger person. There is also a tendency towards an overactive bladder in the elderly due to neural changes (Pfisterer et al 2006).

• The immunological system becomes less efficient thus increasing the incidence of infections. This, coupled with a residual volume of urine in the bladder, increases the likelihood of urinary tract infections. Raz et al (2000) list infections as one of the factors that can cause transient incontinence in the elderly.

In summary, often continence difficulties in the elderly are multifactorial; for example, nocturia may be due to less efficient urine production, decreased antidiuretic hormone, bladder storage problems and sleep related issues (Wein et al 2002).

PSYCHOSOCIAL

DEVELOPMENT OF CONTROL

To acquire continence the child needs to develop physically, mentally and socially. During the first 18 months of life bladder emptying is purely a reflex action. The bladder is stable and empties completely, and Yeung et al (1995) found there is cerebral arousal during emptying. During the first 3 years of life the bladder capacity increases and the frequency of voiding decreases (Jansson et al 2000). Eventually the child then becomes aware of the urge sensation of passing urine and wanting to defaecate, associating this with feeling wet or soiled. The ability to control the bladder and anal sphincters and also the pelvic floor is developed. The sequence of developing control of elimination is normally bowel control when asleep, followed by the child being clean during the day, then the child gaining urinary continence during the day and finally becoming dry at night. There are a number of essential skills the child needs to develop before they are ready for toilet training (Schum et al 2002); gross motor skills of sitting and walking, the fine motor skills involved in dressing and undressing, and communication skills to alert their parent or carer that they need to go to the toilet are essential (Harris 2004). For children with special needs, this signal may be a non-verbal cue or a type of behaviour.

All these factors must be mastered to make ‘potty training’ successful. When the child has developed these diverse skills and is interested in using the toilet, they are ready for toilet training. Time should be given by the parent or carer to help the child get used to the potty or toilet, giving praise and encouragement when the child is successful. Toilet training takes time and accidents can occur, especially if the child is engrossed in play. This may upset the child and the parent.

Physical problems (illness) and emotional worries (parents’ divorce, starting school, etc.) may prolong toilet training, or even cause a child already trained to regress and start wetting again.

Nocturnal enuresis can be defined as involuntary voiding during sleep (Butler 2000). Children who have never been dry at night are classed as having primary nocturnal enuresis, whereas those who have been previously dry for 6 months or more are classed as having secondary nocturnal enuresis. Butler et al (2001) suggest that 15–22% of boys and 7–15% of girls wet the bed regularly at the age of 7 years.

Schum et al (2002) identified 27 skills a child needed to develop for toilet training to be successful.

• List the skills you need to go to the toilet.

• Relate these to a child’s developmental steps.

• Work out what the child needs to be doing to be ‘toilet ready’.

• When working with a health visitor or school nurse you may be able to assess children’s developmental steps and relate it to their toilet readiness.

• Record your learning in your portfolio.

It is thought that bed-wetting may be multifactorial (Enuresis Resource and Information Centre 2002), arising from the three following conditions, known as the ‘Three Systems Approach’:

• Lack of antidiuretic hormone production at night resulting in high night-time urine production (Medel et al 1998).

• Lack of arousal from sleep; being unable to wake from sleep when the bladder is full (Neveus et al 1999).

BEHAVIOURAL FACTORS

Incontinence in an individual cannot always be explained by physical factors alone. The emotional and mental state of the individual, along with his or her attitude, will also have a bearing on the problem. In children, regression may occur when a sibling is born, giving secondary nocturnal enuresis. Encopresis is defined as the passage of normal stool in socially inappropriate places and is found in children with emotional and behavioural problems who need psychological support as part of the child treatment (West & Steinhart 2003).

In an adult the beginning of continence problems can sometimes be traced to emotional traumas, for example bereavement, rejection or moving to a new place (Stokes 2002). Many people become incontinent on admission to residential care or soon after, and this may be related to the loss of independence and personal responsibility and a decreasing sense of self-worth. Duggan et al (2000) found clear evidence that urinary incontinence causes depressive symptoms in older clients.

Continence is an acquired habit, and the motivation to be continent can be diminished in the apathetic or confused elderly person; for example, if a toilet is cold, unpleasant or a distance away, the call to micturate or defaecate may be ignored. Confused or demented people are very dependent upon familiar stimuli in order to maintain their activities (Stokes 2002). Most people have a lifetime of conditioned reflexes to pass urine while seated with no clothing over the genital areas on a toilet in privacy and with the sensation of a full bladder. If an individual is taken to the toilet or sat in a chair with a bare bottom on an underpad, confused messages are given as to where and when to pass urine.

Think of the different public toilets you have visited, both pleasant and unpleasant.

• List what makes these toilets acceptable or unacceptable to you.

• During your allocations look at the patient toilet; is it up to your personal standards?

• Reflect on how an ill or frail person must feel using this toilet and how you may improve it if necessary.

• Record your findings in your portfolio.

STIGMA AND INCONTINENCE

Incontinence can be viewed as a great social stigma. Embarrassment and shame may prevent people reporting their problems with maintaining continence to a health professional (Duggan et al 2000). There are many myths, for example having children causes incontinence, and incontinence is an inevitable part of ageing. Acceptance of these myths may prevent clients, especially women, asking for help (Duggan et al 2001).

Expectation that some sectors of society will be incontinent – e.g. the elderly, people with learning difficulties and women who have had children – encourages passive acceptance of the condition. This is compounded by attitudes of some staff in the caring professions who, for example, accept incontinence as the norm for an elderly person within a nursing home environment (Nazarko 2000).

People often cope by adapting their lifestyle to hide their incontinence by reducing their social activities and not playing sport. Outings by bus or car can be an ordeal because of worrying about being able to get to a toilet when needed, and staying overnight with friends can be out of the question in case of wetting beds or furniture. The guilt, shame, frustration and feelings of the hopelessness of a situation that does not seem to have a solution can cause isolation in all those with continence difficulties. Duggan et al (2000) found patients with urinary incontinence reported loneliness as a major problem, particularly in younger patients.

Butler (2002) looked at the impact of nocturnal enuresis on children and suggested that older children with this condition may exhibit psychological symptoms including low self-esteem and behavioural problems; however, if the bed wetting is treated successfully, no long-term effects were apparent.

Wilkinson (2001) found that Pakistani women with these problems had low self-esteem and had feelings of being unclean and sinful. Muslim women found the worst consequence was that it prevented them praying.

This shame can affect the individual’s sexuality and relationship with those closest to them (Roe et al 1999). There is a high correlation with impotence, and it has been shown that stress incontinence is associated with sexual dysfunction among middle-aged women. The feeling of being unclean or smelly, and perhaps wearing incontinent aids, will hamper a person’s self-image and question their sexual attractiveness. Sexual activity is regarded as a private and personal matter and like incontinence is also taboo. Discussing this dual problem needs to be conducted with delicacy. It is important to remember that clients who have to rely on pads or catheters may still wish to have a sex life, and if these are causing problems, help and counselling should be sought from a specialist.

• How do you feel when you are changing a baby?

• How do you feel when you are changing an elderly person’s wet and soiled bed?

• Are your feelings different; if so why?

• List the things that would cause you concern if you were incontinent?

• With your reflections in mind, list ways that you may be able to support people who have problems with continence.

CARE DELIVERY KNOWLEDGE

ASSESSMENT OF URINARY INCONTINENCE

Care pathways are vehicles for planning patient focused care. Accurate assessment of the individual with incontinence is essential to ensure that the reason for incontinence is found so a pathway with suitable interventions for the specific problems is identified (Brown et al 2006). The NICE guidelines for urinary incontinence (2006: 32) provide a good example of a care pathway for the management of urinary incontinence in women. Ideally the assessment will be multidisciplinary, involving doctors, nurses, physiotherapists and occupational therapists (NICE 2006).

When assessing and caring for a client with elimination difficulties nurses need to understand how the client and carer feel, and also to be aware of their own feelings towards the situation, so that negative attitudes are not transferred from the assessor to the client. The environment should be private and provide a relaxed atmosphere. The assessment should not be rushed and mutually understood terminology should be used. A holistic assessment should include the influencing and functional factors of incontinence as well as the urinary symptoms and specific physical examination (see Table 18.4).

| Mobility | Difficulty in walking to or sitting on the toilet |

| Dexterity | Problems with opening doors or removing clothing |

| Communication | Problems with sight or hearing, speaking |

| Diet and fluids | Amount and type of fluid drunk, type of diet especially the amount of fibre eaten (see Ch. 8, ‘Nutrition’) |

| Elimination | The client’s view of the problem, constipation history |

| Sleep | Tiredness may indicate lack of sleep due to nocturia |

| Psychological | Memory loss, confusion making finding the toilet difficult, behaviour associated with wanting to pass urine, any anxiety or depression caused by the incontinence |

| Environmental | Information about the toilet facilities at the client’s home, location of toilet, up or down stairs, height of toilet, handwashing facilities, privacy |

| Recreational | To what extent has the problem affected their lives, socially, at work, their family, sexual relationships |

| Past medical history | Neurological, urological, and gynaecological problems. In women, details of menstrual cycle/menopause, obstetric history: number of children, weight of babies, type of delivery, were forceps used. In men, prostate history |

Assessment of urinary problems

The assessment should cover:

• urinary symptoms

• baseline chart

• urinalysis

• post-void residual volume

• vaginal examination

• rectal examination.

Urinary symptoms

It is important to gain the client’s perspective in order to determine the severity of the problem. Wetting a teaspoonful a day into a panty liner may not seem much, but to certain individuals this loss of control can be devastating, both psychologically and socially.

Assessing the bladder symptoms and questioning should establish what type of urinary symptoms the client has. Firstly, an overall picture is needed, for example:

• How often do you pass urine? (frequency)

• How long can you hold following the desire to pass urine? (urgency)

• Do you wet before you reach the toilet? (urge incontinence)

• Is it painful to pass urine? (dysuria)

• Do you wake at night to pass urine? (nocturia)

• Do you strain to pass urine?

• Do you have to wait to start? (hesitancy)

• Do you gush or dribble? (poor stream)

• Does your bladder empty without warning? (decreased sensation)

• Do you leak when you cough or laugh? (stress incontinence)

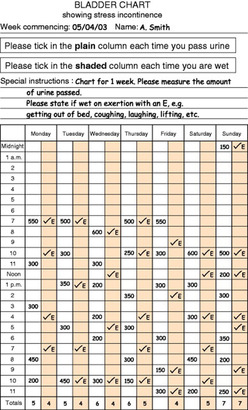

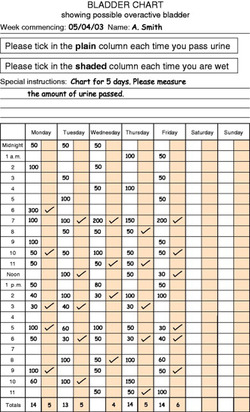

Charting(bladder diary/bladder chart)

To confirm the urinary symptoms, a chart should be filled in, usually by the patient or a carer (Fig. 18.12). The chart should be completed over a minimum of 3 days (Groutz et al 2000). It is the most useful nursing tool in assessing incontinence as part of a baseline assessment and a record of progress during treatment (NICE 2006). A well-kept chart will show times of voiding and episodes of incontinence. If the bladder capacity is needed the volume of urine is also recorded. The fluid intake may also need monitoring if the nurse needs to assess whether the client is drinking enough and has a balanced input and output (see Evolve 18.2).

|

|

| Figure 18.12 |

Urinalysis

A specimen of urine should be taken for testing. The presence of protein or blood will indicate infection and a specimen should be sent to microbiology for culture and sensitivity. If the urine testing sticks are able to identify nitrites then the presence of infection is 90% certain; if no nitrites are present there is no infection (NICE 2006).

Residual volume

A post-void residual volume of urine should be determined on initial assessment using an ultrasound scanner (Goode et al 2000) or by intermittent catheterization. Symptoms of a client with an increased residual volume may mimic the symptoms of detrusor muscle instability. If there is a residual volume and inappropriate treatment is commenced, e.g. drug therapy for bladder spasm, this may cause the volume to become greater and eventually cause hydronephrosis and severe kidney damage.

Physical examination

A nursing assessment should include a physical examination of the client, but the nurse must remember that the patient may find this embarrassing. The perineal area should be examined for signs of infection, prolapse, vaginitis and urethritis. A vaginal examination may need to be done by an experienced nurse if stress incontinence is suspected. The strength of the pelvic floor can be assessed and the ability of the client to identify her pelvic floor muscles (NICE 2006). A digital examination of the rectum may be necessary to diagnose if a man has prostate enlargement; again this should only be done by a nurse specialist or a doctor (Royal College of Nursing 2004).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access