CHAPTER 4 Consent to treatment

Why is consent important?

Assault and battery

Assault can also be, and is most often contemplated as, a criminal offence. However, as far as nurses and other staff working in the health field are concerned, assault as a crime does not have general application. The criminal offence of assault would not only consist of the application of force to another person without his or her consent, but would include the actual intent to cause harm to the person assaulted or a very high degree of reckless indifference to the probability of harm occurring to the person assaulted. It is fortunately rare for such an intention or attitude of mind to prevail among nurses or any other health personnel. Where it does, it would undoubtedly become a professional disciplinary matter as well as a criminal matter.

As far as the civil law is concerned, there is a technical distinction to be made between assault and battery, although for all practical purposes no such distinction is made and the word assault is often used to embrace both actions. To explain the technical distinction, an assault can be committed merely by putting a person in fear for his or her physical wellbeing; for example, shaking a fist in front of a person’s face and threatening to punch the person could well constitute an assault. If such a threat were to be carried out, the actual application of the blow to the person’s body would constitute the technical offence of battery. The offence of battery, it has been said, ‘exists to keep people free from ‘unconsented-to touchings’.1

Any treatment given to a patient without the patient’s consent, or the consent of a person entitled to give such consent on behalf of the patient, constitutes a battery for which the patient is entitled to be compensated by an award of damages. It is a well-established legal principle, which the courts will uphold, that ‘every human being of adult years and sound mind has a right to determine what shall be done with his own body’.2 There are some exceptions to that statement, which have largely been created by statute. Some of these will be dealt with in this chapter and others will be addressed in Chapter 11, Mental Health.

Relevance of consent generally

Clearly, it is the absence of consent which renders an otherwise legitimate act a crime.

Consent as a defence also arises for consideration in relation to civil negligence, where it is otherwise known as the defence of volenti. That defence is explained in Chapter 3, Negligence and Vicarious Liability. Although such a defence has limited application in hospitals and health matters, it is another example of the application of consent as a defence in a variety of legal situations, both criminal and civil.

Negligence must be distinguished

The main reason why patients undergo any form of medical treatment is their belief that their condition will be improved or at least palliated by the treatment given. Reality reveals that normally, if their condition is improved, most patients are happy to let the situation rest even if they did not know the precise details of what had happened to them or even if their treatment was slightly different to that which they had anticipated. An exception to this is where treatment may be given in disregard of a person’s moral or religious convictions; for example, if a Jehovah’s Witness were to receive a blood transfusion. Even if the outcome were successful, the patient may still feel deeply aggrieved.3

Where the two potential causes of action of negligence and battery often overlap, and therefore can confuse the layperson, is what is often described (erroneously) as informed consent. For legal purposes, there are two distinct areas of law in play here. The question of adequately informing a patient in ‘broad terms of the nature of the procedure which is intended’ is critical to the issue of obtaining a valid consent as a defence to an action in battery.4 However, the failure of a medical practitioner to inform a patient adequately about the treatment he or she is to undergo, particularly the material risks involved and likely outcome of any proposed treatment, can and has been determined by the courts to be negligence.5 In other words, such a failure will, more often than not, be deemed to be a breach of the doctor’s duty of disclosure, as part of his or her duty of care to the patient. That important distinction, together with the relevant cases and the views expressed by the courts, is set out in Chapter 3, Negligence and Vicarious Liability.

Remember that, in any allegation of negligence, the patient must prove all the necessary elements, including the fact that they have suffered some form of recognisable damage. As far as any action in battery is concerned, the patient does not have to prove damage, but rather an intentional touching and the absence of consent to the treatment given. The amount of compensation awarded by a court in such a situation may be nominal when compared to the compensation awarded if the patient were damaged and could prove negligence. Nevertheless, it is possible for a patient to bring an action seeking compensation for battery in the absence of any negligence on the part of the person concerned and solely on the basis that consent was not given to the type of touching which occurred. A case precisely on this point was the Canadian case of Malette v Shulman et al. which was decided in 1991.6 Although the decisions of Canadian courts are not binding on Australian courts they would be considered to be persuasive precedent. The case is particularly interesting because it demonstrates the distinction between an action in negligence and battery and at the same time it reinforces the right of a person to withhold consent to treatment — in this case a blood transfusion. The relevant facts of the matter are set out below.

It is important to note here that Dr Shulman was not found liable for any negligence in his treatment of Mrs Malette: he had acted promptly and professionally and was well motivated throughout and his management of the case had been carried out in a competent, careful and conscientious manner in accordance with the requisite standard of care. His decision to administer blood in the circumstances confronting him was found to be an honest exercise of his professional judgment which did not delay Mrs Malette’s recovery, endanger her life or cause her any bodily harm. Indeed, the doctor’s treatment of Mrs Malette may well have been responsible for saving her life.7

Despite the above comments the court upheld Mrs Malette’s claim against Dr Shulman on the basis that he had violated Mrs Malette’s ‘rights over her own body by acting contrary to the Jehovah’s Witness card and administering blood transfusions that were not authorised’.8 The court awarded Mrs Malette $20 000 damages but declined to make any award of costs — in other words, Mrs Malette would have had to pay her own legal costs out of the damages awarded. Compared with the amount of damages awarded by courts today for negligence actions, Mrs Malette’s damages of $20 000 for battery would certainly be considered nominal, particularly as she had to pay her own legal costs. There are a number of more recent cases involving blood transfusions and Jehovah’s Witnesses, and not all the decisions are as clear cut as this one.9 However, Malette v Shulman does provide a clear example of what the tort of battery is intended to do, which is to uphold the right of individuals to control what happens to their own body.

What information is available to help professionals and patients?

Clearly these matters are extremely complex and there are many useful documents available to assist healthcare professionals and consumers alike both to understand the law and to provide the best available information and practices. For healthcare practitioners, there is a range of useful information. For example, the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) has recently updated its General Guidelines for Medical Practitioners on Providing Information to Patients.10 They have also produced a companion document Communicating With Patients: advice for medical practitioners. Although these documents inexplicably only refer to the information and communication practices of medical practitioners, they will be of equal value for nurses and allied health practitioners who provide information about treatment and care for patients. State and territory governments also produce comprehensive policy documents relating to consent for medical treatment. Two recently updated policy examples (NSW, 2005 and WA, 2006) are provided in the endnotes, both of which are extremely comprehensive and a valuable resource for any healthcare professional who wishes to understand not only the law, but also how the law operates in practice.11 In addition, there are many useful consumer information documents — some developed by government and others developed by consumer organisations. The Consumers’ Health Forum of Australia (CHF) recommends a simple decision-making model which identifies that consumers need information about options, outcomes and incidence. These are defined as follows:

How may consent be given?

Implied consent to treatment can be given in a variety of ways and is most often used as the method of giving consent to a simple procedure of common knowledge. For example, a nurse might request a patient to hold out his or her arm for an injection or to roll over preparatory to being given an injection in the thigh and the patient’s compliance with such a request would normally imply consent to that treatment. Even though a patient may appear to be implying consent for the intended procedure by their actions, it is good practice to explain fully to the patient what you are going to do, regardless of any behaviour that may imply consent. In addition, the element of common knowledge means that it is not sufficient to make the claim that a person has given consent to a treatment ‘simply by turning up at the hospital’. In the 1984 deep sleep therapy (DST) case of Hart v Herron, the Supreme Court held that turning up at the hospital was not sufficient to imply consent for treatment, and the defendant in this case was found to be liable in battery for administering the DST.13 DST does not constitute a simple procedure of common knowledge. Quite clearly it is not possible to consent to a procedure about which you have neither knowledge nor understanding, as a person cannot agree to that which they have not contemplated.

What are the elements of a valid consent?

That any consent given is freely and voluntarily given

if a medical practitioner or a nurse advises a patient that he or she must have a particular form of treatment or else he or she will be discharged

if a medical practitioner or a nurse advises a patient that he or she must have a particular form of treatment or else he or she will be discharged the authoritative role of the medical practitioner may introduce an element of coercion into the consent procedure on the basis of ‘I know what’s best for you’

the authoritative role of the medical practitioner may introduce an element of coercion into the consent procedure on the basis of ‘I know what’s best for you’ if it can be established that any coercion or duress was brought to bear on a patient in order to obtain his or her consent, that consent will be invalid.

if it can be established that any coercion or duress was brought to bear on a patient in order to obtain his or her consent, that consent will be invalid.Some who did know, if they refused to sign the consent form, then the instruction was that you gave them some medication to quieten them down; that’s what you would say, ‘I’ll give you this little injection now, it will calm you down. You will feel a lot better after it’. But of course that little injection was Sodium Amytal and I think some Valium as well and then of course they were off on the sedation.15

That the patient is informed ‘in broad terms of the nature of the procedure which is intended’16

It is this element that probably gives the greatest concern to nursing staff, largely because of the problems that arise in relation to written consent forms. From a strict legal perspective the term ‘informed consent’, that can be traced to early American decisions,17 is no longer considered to be appropriate, confusing as it does the requirement for consent in defence to actions in battery and the requirements for information-giving about material risks, the absence of which forms one of the elements of an action in negligence. However, in reality, people need not only to be informed in broad terms, (thus providing a defence against an action in battery) but also to be informed about the material risks (thus providing a defence against a potential action in negligence).

How much information does the patient require to make a decision to consent to treatment?

At this point it is necessary to restate that, invariably, when this issue is considered it is done within the context of negligence, having regard to the perceived duty of the doctor to inform the patient adequately about the material risks inherent in any proposed treatment, and readers should refer to the cases on this issue in Chapter 3, Negligence and Vicarious Liability. That is not to suggest that an action in battery cannot or should not be pursued. It simply reflects the views expressed by the courts in Australia and elsewhere, particularly in England, on this issue. Indeed the decision of the High Court of Australia in Rogers v Whitaker makes it quite clear that actions against medical practitioners alleging inadequacy of information about a proposed treatment should properly be considered as part of the medical practitioner’s duty of care within the context of an action in negligence.18 The facts of Rogers v Whitaker are set out in Chapter 3, and should be referred to. The facts reveal that Mrs Whitaker received precisely the treatment to which she had consented, thus there could be no successful action in battery. In unanimously dismissing Dr Rogers’ appeal the High Court made the following comment on the issue of informed consent:

… In this context nothing is to be gained by reiterating the expressions used in American authorities such as ‘the patient’s right of self-determination’ or even the oft-used and somewhat amorphous phrase ‘informed consent’. The right of self-determination is an expression which is, perhaps, suitable to cases where the issue is whether a person has agreed to the general surgical procedure or treatment, but is of little assistance in the balancing process that is involved in the determination of whether there has been a breach of the duty of disclosure. Likewise, the phrase ‘informed consent’ is apt to mislead as it suggests a test of the validity of the patient’s consent. Moreover consent is relevant to actions framed in trespass, not in negligence. Anglo-Australian law has rightly taken the view that an allegation that the risks inherent in a medical procedure have not been disclosed to the patient can only be found an action of negligence and not in trespass; the consent necessary to negative the offence of battery is satisfied by the patient being advised in broad terms of the nature of the procedure to be performed.19 [emphasis added]

In 2004 the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) updated its General Guidelines for Medical Practitioners on Providing Advice to Patients.20 The advice reads as follows:

the likely consequences of not choosing the proposed diagnostic procedure or treatment, or of not having any procedure or treatment at all;

the likely consequences of not choosing the proposed diagnostic procedure or treatment, or of not having any procedure or treatment at all; any significant long term physical, emotional, mental, social, sexual, or other outcome which may be associated with a proposed intervention;

any significant long term physical, emotional, mental, social, sexual, or other outcome which may be associated with a proposed intervention; the seriousness of the patient’s condition; for example, the manner of giving information might need to be modified if the patient were too ill or badly injured to digest a detailed explanation;

the seriousness of the patient’s condition; for example, the manner of giving information might need to be modified if the patient were too ill or badly injured to digest a detailed explanation; the nature of the intervention; for example, whether it is complex or straightforward, or whether it is necessary or purely discretionary. Complex interventions require more information, as do interventions where the patient has no illness;

the nature of the intervention; for example, whether it is complex or straightforward, or whether it is necessary or purely discretionary. Complex interventions require more information, as do interventions where the patient has no illness; the likelihood of harm and the degree of possible harm — more information is required the greater the risk of harm and the more serious it is likely to be;

the likelihood of harm and the degree of possible harm — more information is required the greater the risk of harm and the more serious it is likely to be; the questions the patient asks; when giving information, doctors should encourage the patient to ask questions and should answer them as fully as possible. Such questions will help the doctor to find out what is important to the patient;

the questions the patient asks; when giving information, doctors should encourage the patient to ask questions and should answer them as fully as possible. Such questions will help the doctor to find out what is important to the patient; the patient’s temperament, attitude and level of understanding; every patient is entitled to information, but these characteristics may provide guidance to the form it takes; and

the patient’s temperament, attitude and level of understanding; every patient is entitled to information, but these characteristics may provide guidance to the form it takes; and allow the patient sufficient time to make a decision. The patient should be encouraged to reflect on opinions, ask more questions, consult with the family, a friend or advisor. The patient should be assisted in seeking other medical opinion where this is requested;

allow the patient sufficient time to make a decision. The patient should be encouraged to reflect on opinions, ask more questions, consult with the family, a friend or advisor. The patient should be assisted in seeking other medical opinion where this is requested; pay careful attention to the patient’s responses to help identify what has or has not been understood; and

pay careful attention to the patient’s responses to help identify what has or has not been understood; and if the doctor judges on reasonable grounds that the patient’s physical or mental health might be seriously harmed by the information; or

if the doctor judges on reasonable grounds that the patient’s physical or mental health might be seriously harmed by the information; orHaving regard to all of the above, the issue of how much information a person requires to decide to consent to treatment can be summarised as follows:

the information element of a valid consent is the gathering together of the information needed to allow a patient to arrive at a decision that the patient believes is in his or her own best interests;

the information element of a valid consent is the gathering together of the information needed to allow a patient to arrive at a decision that the patient believes is in his or her own best interests; if there were to be any statement of general legal propositions applicable in Australia, it would be that, in obtaining a valid consent, a patient must be given sufficient information to be able to understand the nature and consequences of the proposed treatment; and

if there were to be any statement of general legal propositions applicable in Australia, it would be that, in obtaining a valid consent, a patient must be given sufficient information to be able to understand the nature and consequences of the proposed treatment; and failure to advise and inform a patient properly about the nature and consequences of the proposed treatment as well as its material risks would, in most instances, amount to a breach of the doctor’s duty of care, which could, should damage ensue, make the doctor liable in negligence, quite apart from any action in battery.

failure to advise and inform a patient properly about the nature and consequences of the proposed treatment as well as its material risks would, in most instances, amount to a breach of the doctor’s duty of care, which could, should damage ensue, make the doctor liable in negligence, quite apart from any action in battery.Who is responsible for giving sufficient information to a patient?

… authorised nurse practitioners may initiate medications, order diagnostic tests and make referrals only when they are operating under guidelines approved by the Director-General. Nurse practitioners have the same obligations as do medical practitioners, when obtaining consent for the procedures which they are authorised to perform.22

Both of these issues will now be examined.

Written consent forms

For many years hospitals insisted that nurses were responsible for obtaining a patient’s signature on consent forms. It is pleasing to note that key policy documents have now taken that responsibility from nursing staff and placed it where it rightfully belongs — with the medical officer or other treating practitioner concerned.

Always ensure that the consent form is completely filled in. A patient should never be asked to sign a blank consent form.

Always ensure that the consent form is completely filled in. A patient should never be asked to sign a blank consent form. If a patient wishes to alter the consent form in any way by adding or crossing out words, then the nurse must advise the treating doctor as soon as possible.

If a patient wishes to alter the consent form in any way by adding or crossing out words, then the nurse must advise the treating doctor as soon as possible. If a patient starts to ask the nurse questions concerning the nature and extent of the procedure to which the patient is consenting, the nurse should offer to ask the patient’s treating doctor to come and talk to the patient. In contacting the treating doctor, the nurse should make a relevant entry in the patient’s records, as well as noting the doctor’s response to the request.

If a patient starts to ask the nurse questions concerning the nature and extent of the procedure to which the patient is consenting, the nurse should offer to ask the patient’s treating doctor to come and talk to the patient. In contacting the treating doctor, the nurse should make a relevant entry in the patient’s records, as well as noting the doctor’s response to the request. If a patient refuses to sign a consent form, the treating doctor must be advised and a relevant entry made in the patient’s record. In a hospital, the appropriate administrative personnel should also be advised.

If a patient refuses to sign a consent form, the treating doctor must be advised and a relevant entry made in the patient’s record. In a hospital, the appropriate administrative personnel should also be advised.The professional responsibility to inform

Nursing staff do have a professional responsibility to educate patients and to provide secondary information about a particular treatment once the course of treatment has been agreed upon. Nursing staff are often questioned by patients about the treatment they are undergoing. They are the most frequent source of contact and conversation in a hospital and patients often relate more readily to the nursing staff for that reason. It is completely appropriate for nursing staff to provide the best advice and information available and to answer patients’ questions honestly and helpfully in relation to the agreed treatment, and significant advantages are known to attach to the provision of pre-operative information.23 However, there have been occasions where nurses have found themselves in the difficult position of caring for a patient who, they believe, has not received sufficient information concerning the particular treatment he or she is undergoing or the alternative courses of treatment which may be available to the patient. The most frequent problem has been in relation to the treatment of patients for various types of cancer, which quite often involves the administration of large doses of cytotoxic drugs and radiotherapy. This type of treatment sometimes results in physically and mentally distressing side effects for the patient which, if the patient’s life expectancy is quite limited, can cause nurses to question the efficacy of the treatment. In such a situation the nurse must carefully assess his or her professional position before seeking to intrude on the patient–doctor relationship.

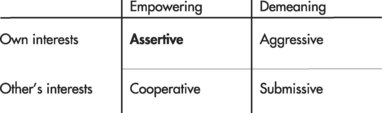

In recent years, there has been a greater emphasis on a systems approach to problems and errors in healthcare. Human beings make mistakes24 and healthcare professionals are no exception.25 The aviation industry has already undertaken a considerable amount of work and has developed the concept of crew resource management, which creates the imperative for each member of the aviation team to speak out forcefully if they believe that there is any problem.26 This work is being replicated in the healthcare sector and there is a prevailing view that all healthcare professionals have a responsibility to speak up (appropriately, as discussed above) to avoid adverse incidents occurring and to report adverse events so that analysis can occur and preventative strategies can be implemented. A strategy for helping those staff who may feel unable to speak out about healthcare concerns is known as graded assertiveness. The Victorian Government has produced a useful presentation to identify how healthcare professionals can use the technique of graded assertiveness to raise questions of concern. They identify a relational matrix (Figure 4.1) and a range of valuable strategies in relation to assessing and implementing assertive behaviours.27