8. Concepts of pain and the surgical patient

Sharon Kitcatt

CHAPTER CONTENTS

Classification of pain104

General principles in the management of acute pain104

Methods of administering postoperative analgesia107

Pharmacology in acute pain management114

The Acute Pain Service team118

At the end of the chapter the reader should be able to discuss the following:

• the classification of pain

• general principles in the management of acute pain

• factors that can affect the experience of acute pain

• pain assessment

• the physiological response to pain and the dangers of poorly managed acute pain

• methods of administering postoperative analgesia

• pharmacology in acute postoperative pain management

• the Acute Pain Service team.

Introduction

Pain is a complex, multidimensional experience and it is unique to the person experiencing it. Pain is often seen as a warning sign that something is wrong and is a common reason for people to consult their general practitioner. The International Association for the Study of Pain (1992:2) describes pain as ‘an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage’.

The management of postoperative pain has received much attention in the past few years, particularly since the publication of the Joint Report of the Royal Colleges of Surgeons and Anaesthetists ‘Pain after Surgery’ (Royal College of Surgeons of England, 1990). This report remains a benchmark for much of the acute pain work that has since been developed, as it highlighted the continuing failings in postoperative pain management and made several recommendations for the improvement of the situation. The development of Acute Pain Services in general hospitals undertaking surgery was one of those recommendations.

Postoperative pain should not be expected or seen as being an inevitable part of recovery and it can be assumed that patients should not suffer unnecessarily. Health professionals have an ethical duty to provide pain relief, and this is reinforced in Article 3 of the Human Rights Act (1998), which states: ‘No one shall be subjected to torture or to inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.’

In addition, poorly managed postoperative pain can activate several physiological responses which can be harmful, and may delay recovery from surgery and ultimately the patient’s discharge from hospital. It is difficult to state that good pain relief alone will reduce length of stay, as this is only one part of the patient’s journey, but it is reasonable to expect that a patient who experiences a manageable level of pain is less likely to experience postoperative complications and hence is likely to recover more quickly.

Unfortunately, it is likely that many patients are still being failed in this area of care due to many factors. An extensive review of postoperative pain management by Dolin et al (2002) suggested that one in five patients still report severe pain postoperatively. Scott and Hodson (1997) suggested that many patients have a poor understanding of how postoperative pain is managed and that this is compounded by some patients wishing to maintain a passive role in this part of their care, preferring to leave decisions about pain to be made by health professionals.

Classification of pain

Acute pain is pain of recent onset and limited duration. It usually has an identifiable cause and an identifiable beginning and end. Acute postoperative pain is nociceptive pain. Nociception is the term used to describe the processing of noxious or damaging stimuli, and nociceptive information is transmitted by specific pain fibres called nociceptors. Tissue injury starts the process of inflammation by stimulating the release of inflammatory mediators such as bradykinin, histamine and prostaglandins from the damaged tissue cells (Kidd and Urban, 2001). This process will cause nociceptors to become further sensitized to pain. Acute pain is also associated with the stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system, which can lead to the activation of several potentially harmful physiological responses. Nociceptive pain can be visceral or somatic. Visceral pain arises from internal organs and may be difficult to localize, whereas somatic pain arises from skin, muscle or joints and tends to be localized.

Chronic pain may be defined as that pain which has persisted, either continuously or intermittently, for 3 months or more and does not respond to traditional medical or surgical treatment. Bonica (1990:19) defined chronic pain as ‘pain that persists a month beyond the usual course of an acute disease or a reasonable time for an injury to heal, or that is associated with a chronic pathological process that causes continuous pain or the pain recurs at intervals for months or years’. Chronic pain is unlikely to stimulate the sympathetic nervous system. However, it can totally disrupt normal life by taking over the life of the sufferer and of those close to them. Chronic pain can be complex and multidimensional in nature, which can lead to the sufferer seeking many different treatments. It is important to note that inadequately controlled acute pain can lead to chronic pain. Macrae (2001) suggested that chronic pain after surgery was a frequently neglected yet common problem, often causing disability and distress. Common operations causing chronic pain after surgery were cited as breast surgery, hernia repair, cholecystectomy and thoracotomy.

Neuropathic pain can be described as pain initiated or caused by a primary lesion or dysfunction in the nervous system. This is a very distressing pain and early diagnosis and treatment is crucial, as it may become more difficult to treat over time. Patients will often describe neuropathic pain as burning, shooting or stabbing in nature and the pain may also be associated with abnormal sensations such as numbness and hyperalgesia. Neuropathic pain can occur following a viral infection such as shingles; following surgery such as amputation; or it may be linked to a medical condition such as diabetes (diabetic neuropathy). An important part of postoperative pain management is the recognition of neuropathic pain. Staff should be alerted to signs of an increase in pain, perhaps of a shooting or stabbing nature, particularly when the level had previously started to diminish. If the pain is requiring increasing amounts of opioids with little or no effect, this may be a sign of neuropathic pain, as generally this pain may not respond well to opioids (Bridges et al., 2001 and National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), 2005).

General principles in the management of acute pain

The patient-driven outcome should be for the patient to report that they are comfortable, or that their pain is at a level which is acceptable to them, with minimal side-effects such as nausea and vomiting or oversedation. Pain must be assessed and recorded regularly, and the assessment acted upon. Pain assessment must involve the patient where possible and should be a dynamic pain assessment, measured on moving or coughing, or during procedures which might cause pain. Recording of pain scores has frequently been inconsistent when compared with vital signs such as blood pressure and respiratory function. Campbell (1995) suggested that pain should be considered to be the ‘fifth vital sign’, assessed and recorded at the same time as recording of vital signs such as temperature, blood pressure and respirations.

As part of pain assessment, it is logical that the effects of analgesics must also be evaluated and reviewed regularly. The strongest available analgesic should be used, and opioid analgesics are the mainstay in the management of moderate to severe pain (NHMRC, 2005). The most appropriate route for administering opioids must be used at that time, although local policies will guide this. For example, epidural analgesia and patient-controlled analgesia may be used in all surgical areas, whereas the administration of intravenous opioids by intermittent bolusing may be limited to a postoperative recovery area or a critical care area.

Multimodal analgesia will improve the effectiveness of the analgesia (NHMRC, 2005). Multimodal analgesia involves the use of different types of drugs that each contribute to analgesia in different ways. Paracetamol administered regularly will provide effective analgesia: administered concurrently with an opioid, paracetamol improves the quality of pain relief (Schug et al, 1998).

What can affect the experience of acute pain?

Pain is a complex interaction of both mind and body, and the outcome of postoperative pain management is subject to many contributing factors. For example, staff and patient attitudes, particularly in relation to fears of addiction from the use of opioids, may prevent a patient from receiving adequate analgesics. Education of all staff involved in the management of patients postoperatively is essential, to ensure that unhelpful attitudes are challenged.

It is important to undertake a full assessment of the patient’s pain history. This should include questions about any previous surgery, previous and current analgesic use, and any fears or misunderstandings about analgesics, such as addiction or side-effects. Patients who have an existing opioid requirement or a substance abuse disorder will have a higher opioid requirement if they have surgery. Other factors such as the age of the patient will affect analgesia requirements. The elderly patient may have other ongoing pain problems due to conditions such as arthritis. They may take lots of different medicines in addition to analgesics (polypharmacy) and they may be stoic about pain, perhaps feeling that it is simply to be expected as part of an ageing life.

A patient’s personality can strongly influence the way in which pain is expressed. A patient who appears quiet and comfortable may not necessarily be so. It has been suggested that people with extroverted personality types are more likely to complain and to express their pain than introverted personality types. If this is so, then it could be argued that extroverts will probably receive more analgesics (Bond, 1984). A person’s culture can also strongly influence perception of pain and how pain is expressed, which will affect the outcome of treatment. In addition, the nurse’s own culture can influence how they assess pain and it is important for nurses to recognize how a cultural bias on their part can affect this (Davitz and Davitz, 1985).

Past experience may be reflected in the response of an individual to pain. Many of these responses are learnt during childhood and carried through into adult life, with associated personal beliefs and coping mechanisms.

It has been suggested that comparable stimuli in different people do not necessarily produce the same pain, either in duration or intensity (Melzack and Wall, 1991). This highlights the misconception that a particular operation or injury will produce a predictable level of pain. Interestingly, most people have a fairly uniform pain sensation threshold, which is the lowest intensity at which pain is felt, but pain perception and tolerance are not static. Pain perception and tolerance can be influenced by feelings of exhaustion, boredom, anxiety and isolation.

Wall (1999) anecdotally describes several reports illustrating how the meaning of the pain can influence the experience of the individual. It is also important to consider what the pain means to the patient and how this links in with the meaning of the surgery. For example, a patient undergoing a joint replacement will know that this is likely to improve their quality of life, whereas a patient who has had surgery related to cancer will have many anxieties due to the potential impact of their disease.

Pain assessment

Pain assessment is the core of effective pain management. The patient must be involved in pain assessment where possible (Royal College of Surgeons of England, 1990), as it is the patient who knows how their pain feels (Moore et al, 2003). A study by Seers (1987) found that nurses frequently recorded the patient’s pain to be less severe than the patient’s own assessment, and it is probable that this still occurs.

As previously discussed, pain assessment should not be viewed in isolation to other observations but should be considered as one of the vital signs. It is important to ascertain what words patients use to describe their pain. For example, health professionals may use the term ‘pain’, which the patient may consider to mean only severe or excruciating pain rather than soreness or aching which can also prevent them from carrying out their daily activities.

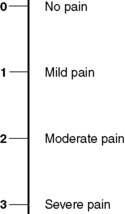

Pain assessment in the acute or postoperative setting tends to focus on pain intensity. Although this may appear to be an overly simplistic measure, it provides a tool to help get treatment as quickly as possible. One of the most common measures in the acute pain setting is the categorical scale (Fig. 8.1) (Moore et al, 2003). This uses words such as ‘no pain’, ‘mild pain’, ‘moderate pain’ and ‘severe pain’ to describe the magnitude of pain. Numbers can be added alongside this verbal description to help the patient to use the tool and also to assist with analysis of data for audit purposes.

|

| Figure 8.1 • Categorical pain scale. |

Pain assessment using the categorical scale may be difficult for some patients, such as the elderly or cognitively impaired. Pain assessment in the elderly must also consider other coexisting pain problems, which must be distinguished from the acute postoperative pain (Moddeman, 2002). Elderly patients may also be cognitively impaired, which can make pain assessment difficult. The use of standard pain tools should not be automatically excluded for these patients because additional simple, specific questioning can still be helpful (Victor, 2001). Victor (2001) also recommended the use of other measurements such as facial expression, sweating, increased heart rate, agitation and guarding. The Abbey Scale is a tool that uses six behavioural indicators to help measure pain in patients with dementia (Abbey et al, 2004).

Despite variation among patients in their ability to use some tools, it is often necessary to standardize pain assessment tools, to avoid uncertainty when staff move between areas in one hospital. Patients undergoing elective surgery should be introduced to a pain assessment tool preoperatively and written information given about how to use the tool and what to do if their pain is not controlled. The preoperative assessment clinic may be an ideal environment for the dissemination of this preoperative information, although it must be recognized that patients are given a great deal of information at that time and this may need revisiting on admission.

The physiological response to pain and the dangers of poorly managed pain

Severe acute pain can be physiologically harmful due to the stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system. The role of the sympathetic nervous system is to protect the body in times of stress, and stimulation causes several physiological responses known as the ‘surgical stress response’. These include the release of hormones such as cortisol and growth hormone; increased levels of blood glucose; and fluid and electrolyte imbalances. Increased metabolism will lead to an increased catabolism, requiring higher levels of oxygen. It has been suggested that the provision of adequate pain relief, utilizing epidural analgesia containing a local anaesthetic, may reduce this automatic response (Kehlet and Holte, 2001).

Poorly managed acute pain may be particularly harmful to the elderly or those with pre-existing cardiac morbidity, because of the resulting increased workload on the heart. More oxygen will be required if the heart is forced to work harder and this could be compounded further if the patient is unable to breath properly due to pain, resulting in lower oxygen availability. The elderly patient will also have an altered response to analgesics due to physiological changes such as a lower circulating blood volume and reduced muscle mass (Cooper, 2002). Reduced hepatic metabolism and renal function will mean that the elderly patient is likely to require smaller doses of opioids (Neal, 2001). In addition, frequent polypharmacy in the elderly patient may make them more susceptible to adverse drug reactions.

Methods of administering postoperative analgesia

The administration of strong opioids is the first-line treatment for pain following surgery. The route of analgesic administration will be dependent on the type of surgery and also on the environment where the patient is being cared for. For example, patients with continuous epidural analgesia may need to be nursed in a high-dependency setting, while patients undergoing day case surgery will require shorter-acting opioids to enable them to go home as planned.

Oral administration

Oral administration of analgesics is the most acceptable route for patients, and it should be the first choice if possible. However, this route is seldom appropriate in the immediate postoperative phase, as gut motility is often reduced or the type of surgery may make this route impossible. If the oral route is used inappropriately, then there can be delayed absorption at an unpredictable time and if the patient is nauseated or is vomiting, there will be very little absorption of the drug.

Rectal administration

Analgesics such as paracetamol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be administered rectally, although this method may not be acceptable to patients and it is therefore essential that verbal consent is obtained and recorded prior to administering drugs rectally. Absorption may be unpredictable and some NSAID suppositories can directly irritate the rectal tissues. The wide availability of intravenous forms of paracetamol and NSAIDs should reduce the need to use the rectal route in the postoperative setting.

The intravenous route

The intravenous route is a rapid way of administering analgesics, including opioids, paracetamol and some NSAIDs. The administration of opioids by this route is often limited to clinical areas where there are high staff:patient ratios. The intravenous route is fast acting and easy to titrate to pain levels, but it requires the nurse to stay with the patient during administration and for some time afterwards. This close level of supervision may not be possible in a busy general ward; hence, this method is frequently reserved for use in more specialist areas or by an Acute Pain Service in general wards. Goodman and Gilman (1996) suggested that respiratory depression following the administration of intravenous opioids was most likely to occur within 7–10 minutes of administration; hence, it could be argued that the nurse would need to stay with the patient for at least 10 minutes following the last bolus injection. Best practice would also suggest that naloxone should be immediately available during administration, and that the nurse administering the opioid would remain responsible for the safekeeping of any unused portion of the drug until no more was required and any remainder could be discarded.

The use of a continuous intravenous opioid infusion is another method of administering opioids. However, this may lead to accumulation of the analgesic, so patients should be nursed in an area where they can be closely observed for the whole time that they are receiving opioids by this route (Dodds and Hutton, 2002).

The intramuscular route

The intramuscular route can be used for the intermittent ‘as required’ dosing of opioids and remains the traditional method of administering analgesics postoperatively. However, this method is rarely used, due to the wider use of more effective methods of analgesia. The intramuscular route commonly fails for several reasons. Most patients do not like injections, because they are painful. The nurse has control of the analgesia instead of the patient, and many patients worry about bothering the nurses if they are in pain, especially if the nurses look busy. Additionally, the prescribing and administration of intramuscular opioids may be inadequate and the pharmacokinetics are unpredictable, which may lead to intermittent analgesia and sedation, identified by Lovett et al (1994) as a bolus comfort sedation cycle.

However, the intramuscular route of administering opioids may be the most appropriate route of administration for a particular clinical setting, perhaps if that area has no staff trained in the management of epidurals or intravenous patient-controlled analgesia. It would seem reasonable therefore to make some effort to make this a more reliable and effective method of analgesia. One recommendation of the Joint Report of the Royal Colleges of Surgeons and Anaesthetists ‘Pain after Surgery’ (1990) was to utilize existing methods of analgesia more effectively and challenge traditional beliefs and attitudes. Harmer and Davies (1998) demonstrated that the introduction of a management algorithm allowing the hourly administration of opioids via an indwelling intramuscular cannula could improve patient experience whilst enabling staff to work within a much more flexible but safe system. Hourly administration of intramuscular opioids was also recommended by Dodds and Hutton (2002), who felt that this would be advantageous not only because patients would be less likely to experience peaks and troughs of analgesia but also because the dose could be more easily titrated and patients would have their pain assessed more frequently along with other vital signs. However, it was also recognized that such a change in practice may increase the workload for nursing staff if two nurses were required to check the analgesics. The subcutaneous route can also be used for the intermittent administration of opioids. This route requires no alterations to dosage or frequency of dosing as the absorption of the drug is similar to when given intramuscularly (Macintyre and Ready, 1997) and an indwelling cannula can also be used, as described above.

Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA)

PCA is a common method of administering postoperative analgesia and many patients have benefited from using it. PCA empowers the patient to self-administer analgesics quickly within set parameters. Patients may also prefer PCA to other methods of analgesia as they may feel that they are less bother to the nurses (Seymour 1996). The aim of PCA is to keep plasma levels of opioid at a consistent, effective level without causing peaks and troughs of analgesia.

PCA is frequently used for both adults and children postoperatively. The most obvious criteria for its use are that the patient is physically able to use the chosen device and that they have the ability to understand the concept. Some patients may not feel that PCA is appropriate for them, as they may not wish to take control of this part of their care or they may associate the use of an opioid with drug addiction.

To help ensure best practice in the use of PCA, every step must be taken to reduce risk, such as the standardization of equipment and the use of prescribing guidelines or protocols. Any changes made within these to allow for individual patient need must be made absolutely clear by the prescriber and observation parameters may need to be altered as well. Administration lines used must be designed for PCA use, incorporating a one-way valve port for the safe attachment of intravenous infusions plus an anti-siphon valve to prevent gravity-induced siphoning which could occur if the PCA pump is placed too high. All staff using PCA equipment must be trained in its use, and this training must be provided as an ongoing programme.

It is important that all staff caring for patients using PCA can confidently manage the equipment. This must include being able to check the pump settings against the prescription chart, and monitor and confirm the amount of drug administered and the number of bolus demands, including unsuccessful demands. This information should be recorded with each set of observations, and each time a different nurse takes over the care of the patient. Staff must also be able to troubleshoot potential problems with the equipment and replace PCA syringes or infusion bags as needed, to ensure that the patient does not have a break in analgesia.

Description of terms used in patient-controlled analgesia

It is important to understand the terminology used for PCA. The bolus dose is the amount of analgesic drug that the patient will self-administer on a successful demand with PCA. The bolus should be enough to provide good analgesia with minimal side-effects. Morphine is frequently used for PCA and a 1 mg dose every 5 minutes, if required, appears to be a fairly standard dose for most adult patients. This would appear to go against the argument that we should be providing analgesia which is tailored to the individual, but consistency in prescribing is necessary to help reduce risk.

The lockout time is the time during which the PCA pump will not deliver any dose of analgesic. The patient must be reassured that the PCA will not give a dose of analgesic during this time, no matter how many times the demand button is pressed. Lockout times of between 5 and 10 minutes are commonly used, although it is accepted that this may not be long enough for the full effect of some drugs to be seen (Macintyre, 2001).

When setting up a PCA, initial analgesia in the form of an intravenous loading dose may be needed as the small amount of drug given with each patient bolus may not be adequate for a patient who is in severe pain. The loading dose will help to establish an effective level of analgesia which the patient can then maintain with PCA. The loading dose is given by a doctor or a nurse who has received the appropriate training. The amount of analgesic given as a loading dose will depend on the individual analgesic requirement for each patient. The loading dose can be given as a separate injection but ideally it should be given by utilizing the ‘clinician’ override facility on an electronic PCA pump.

Patient education

Patients must have a clear understanding of how to use the PCA equipment prior to using it. This may be difficult if the patient is undergoing emergency surgery or if they are given information too far in advance and their understanding of how to use the PCA is not rechecked. A study of patients using PCA suggested that structured teaching may make a difference as to how patients managed their pain with this method (Timmons and Bower, 1993). However, Chumbley et al (2004) found that although the use of an information leaflet appeared to be more effective in informing patients about PCA than was verbal information from a pain nurse, there was little effect on pain relief.

Common problems with patient-controlled analgesia

If the patient is not receiving adequate analgesia, the nurse should check that the patient is using the PCA equipment correctly. The pump history must be checked, as the patient may not be using the pump enough due to a lack of understanding. If the patient is not using the PCA appropriately, then further advice and support can be given to help the patient to get the greatest benefit.

The nurse should also ensure that the patient has simple analgesics such as paracetamol prescribed alongside the PCA and ensure that these are given, as these will improve the quality of analgesia (Schug et al, 1998). If no regular, simple analgesics are prescribed, then it is the responsibility of the nurse to get the analgesic prescription reviewed. If the patient has used the PCA to the maximum and has received other analgesics but the level of pain remains unacceptable to them, then their drug regimen must be reviewed. An intravenous ‘rescue’ dose may be required to reinstate analgesia or the bolus dose may need to be increased for that patient. Some patients may be known to have a higher opioid requirement, such as those with a known or suspected substance abuse history. Postoperative care of this client group must encompass effective pain management while preventing physical withdrawal symptoms (Jage and Bey, 2000). Maintenance of their usual opioid requirement in addition to postoperative analgesics can be provided with a background infusion plus PCA or by prescribing a higher PCA dose. This approach may also be appropriate for other patients who take regular opioid-based analgesics, including patients with cancer or chronic non-malignant pain problems.

It is not appropriate to give an opioid intramuscularly as an addition to PCA, as the effect of this may be unpredictable and could lead to oversedation and respiratory depression.

Patients using PCA may also report pain on waking from sleep. It could be argued that a solution to this problem is to give the patient a continuous background infusion of opioid in addition to PCA, but this may simply lead to a higher incidence of side-effects such as respiratory depression rather than an improvement in analgesia (Macintyre, 2001).

Morphine is the most common drug used for PCA but other drugs are also used, including diamorphine, fentanyl and oxycodone. Pethidine is not recommended for PCA use, as the potentially high dose that could be used may lead to the accumulation of the toxic metabolite norpethidine, particularly during the first 24 hours of use (Macintyre, 2001). PCA is commonly administered intravenously, but the subcutaneous route can be used.

All opioids administered by any route have the potential to cause oversedation and respiratory depression (see p. 114). Whenever PCA is prescribed and used, the staff caring for the patient must be able to recognize these problems early on, and follow clear guidelines for subsequent management of the patient. Patients using PCA must only be nursed throughout the 24-hour period in clinical areas where the staff have received the appropriate training. This must be understood by and strictly adhered to by all staff, including the prescribing doctor. It is considered good practice to prescribe oxygen therapy for all patients who are receiving PCA for the duration of PCA use (Dodds and Hutton, 2002).

It could be argued that if the patient is using the PCA unaided, then the natural control would be that they would stop using it if oversedation occurred. However, oversedation is a possibility, particularly if another person is pressing the demand button on behalf of the patient. The basic principle of PCA requires only the patient to press the button and if they became too drowsy to press the demand button, then they would not do so. However, if another person such as a family member or a healthcare professional presses the button, this would override the natural control loop and the patient could easily become overdosed. Visitors are to be actively discouraged from pressing the PCA demand for a patient and must be informed of the potential dangers of doing so. If the patient is unable to understand how to use the PCA or is unable to press the demand for themselves without prompting, then the PCA must be discontinued and an alternative method of analgesia prescribed.

Oversedation may be a more accurate early indicator of opioid-induced respiratory depression (NHMRC, 2005). If a patient becomes sedated at a level such that they are difficult to rouse or they are unrousable, then the PCA handset must be removed from the patient and the patient closely observed until they become less sedated. Close observation means direct observation by a trained nurse who is also constantly monitoring sedation, respiratory rate and oxygen saturations, because a reduced level of sedation such as this is likely to be accompanied by a reduction in respiratory function such as reduced oxygen saturations and respiratory rate. If the nurse is concerned about the patient’s respiratory function and level of sedation, then the nurse should communicate this to medical staff immediately and ensure that naloxone is available and ready for rapid use if required to reverse the action of the opioid. Local policies will dictate at which point naloxone should be used and whether nursing staff are able to administer it.

The patient may show other signs of opioid overdose such as constricted pupils (myosis) and cyanosis. Other potential side-effects of opioids such as pruritus, nausea and vomiting, hypotension and constipation are discussed in the pharmacology section of this chapter.

Regional analgesia

Spinal injections

Drugs injected below the dura, directly into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), are called ‘spinal’ or ‘intraspinal/intrathecal’ injections. Injection of a local anaesthetic is called ‘spinal anaesthesia’, whereas injection of an opioid is called ‘spinal analgesia’. Some patients will have their surgery carried out under spinal anaesthesia (instead of or in addition to a general anaesthetic) and the effect of the drugs may last for several hours. Some patients may have a combined spinal epidural (CSE); this is a spinal injection followed by an epidural using the same catheter.

Spinal anaesthesia will provide a dense motor block which can last for several hours. Staff may be concerned about sitting patients up or allowing them to mobilize following this procedure. Patients can sit up as their general condition allows, but they should not mobilize until they have full motor power in their legs and, even then, initial mobilization must be under the supervision of two members of the clinical staff. Motor power is tested by asking patients to bend their knees and to perform a straight leg raise, which will demonstrate quadriceps strength. Patients may also experience urinary retention due to blocking of the sacral autonomic fibres. Opioids administered spinally without a local anaesthetic will not cause a motor block.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access