Chapter 33 Completing the midwife–woman partnership

Learning outcomes for this chapter are:

1. To explain the importance of a thorough physical, mental and social assessment of the woman and baby before transfer from the maternity carer to well woman/well child carers

2. To establish what constitutes normal six-week developments for the woman/family and for the baby

3. To identify what should be conveyed in referral notes to well woman/well child carers and what may require earlier referral

4. To discuss the methods of family planning appropriate for the woman and her partner, and the provision of information and advice, and ordering/prescribing for a method within the norms and legislation of New Zealand and/or Australia, according to the woman’s informed choice

5. To explain the requirements for documentation of the completion of care and safe, comfortable closure of the professional friendship and partnership with the woman and her family

6. To highlight the important aim of care in the puerperium, which is to affirm the woman’s parenting decisions, build self-esteem and boost confidence in parenting independently.

This chapter outlines a model final assessment by the midwife, of the woman and her baby. This assessment ordinarily includes: modified physical assessments of both mother and baby; a final review of the mother’s mental wellbeing; contraception needs/choices; cervical screening; referral to well child and well woman providers; and a final debriefing of the maternity experience and reflection on care. The chapter concludes with final documentation requirements and an indication of the role of the subsequent Midwifery Standards Review process.

THE WOMAN’S HEALTH

In New Zealand under Section 88 of the New Zealand Public Health and Disability Act 2000, the Lead Maternity Carer (LMC) is responsible for, in addition to a detailed clinical examination of the baby prior to transfer to a well child provider (WCP), a postnatal examination of the mother at a clinically appropriate time, prior to discharge from the LMC’s services (New Zealand Government 2007). At this time there is no such requirement for midwives in Australia. Nevertheless, Australian midwives do provide assesments of women and babies prior to discharge from maternity service.

The midwife’s approach to the final assessment should be a holistic one, seeking information on the woman’s current health status and following up on issues that have arisen in the previous six weeks (e.g. with regard to the woman’s physical health). There is literature that draws attention to the following physical symptoms at six weeks that are typically played down by postpartum women: backache, perineal pain (whether or not there is a healing wound), urinary incontinence, sexual problems, haemorrhoids, constipation, faecal incontinence, headaches, fatigue and recovery from infection (of, as examples, a caesarean wound or episiotomy wound) (Glazener et al 1995, cited in Symon et al 2003; MacArthur 1999).

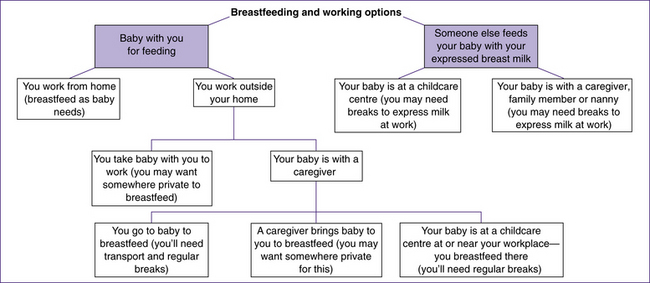

Those mothers who plan to return to work or study, prior to their baby reaching six months, may well need advice and support to continue exclusively or fully breastfeeding. Hopefully, this issue will have arisen in discussion much earlier in your care than at the discharge check. Among the information the woman will require is an explanation of why it is important to continue breastfeeding until six months, and how to inform and gain the support of her employer—for example, the advantages of a family-friendly workplace include happier workers who take less time off due to baby illness. Figure 33.1 shows some options to discuss with women who intend to work and breastfeed. It is recommended that you discuss and leave clear written instructions regarding expressing milk, storage and hygiene. The woman will also require local information on organisations specialising in breastfeeding support; for example, the Australian Breastfeeding Association runs a 24-hour telephone help line.

Emotional health

This is nicely described in the context of postnatal care in general, and concluding the partnership at the six-week discharge visit in particular, by this consumer’s urging to New Zealand LMC midwives: ‘write the ending of the story with each woman’ (Anon 2009, p 24). Aside from assessing the woman’s emotional health for anything that is concerning, the midwife contributes so much to the emotional health of all her clients by concluding the partnership in a timely, respectful, expectation-checking, and mutually satisfying way.

The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPNDS) questionnaire has not been universally applauded as effective (Forman et al 2000; Shakespeare et al 2003). However, Barclay and Lie (2004), after a chart review conducted by investigators from the University of Rochester School of Medicine in New York, reported that ‘the EPNDS should be considered for use in screening for post partum depression (PPD) in the first year well-child visit setting’. ‘Adequate quality control measures need to be in place for consistent implementation’; they also stated that ‘the EPNDS results in higher rates of detection of maternal depression during the postpartum year’ (Barclay & Lie 2004). This screening device is used by some New Zealand midwife LMCs to assess the need to refer with possible pathological postnatal distress/depression.

Dr Gillian White compared the EPNDS with the Postpartum Depression Screening Scale (PDSS) (White 2008). She concluded that in the specific group of women tested, both had satisfactory reliability and validity. One caution related to the use of EPNDS with women who are highly anxious. The PDSS short form is available for download; see Online resources.

Kabir and his colleagues promote three key questions of the 10, questions 3, 4 and 5, which may result in better compliance with screening (Kabir et al 2008).

Box 33.1 Edinburgh postnatal Depression questions

1. I have been able to laugh and see the funny side of things

2. I have looked farward with enjoyment to things

3. I have blamed myself unnecessarily when things went wrong

4. I have been anxious or worried for no good reason

5. I have felt scared or panicky for no very good reason

6. Things have been getting on top of me

7. I have been so unhappy that I have had difficulty sleeping

8. I have felt sad or miserable

9. I have been so unhappy that I have been crying

Box 33.2 Support groups

Does the woman know what resources are available for support for postnatal distress? For example, the following website provides contact details of consumer mental health support groups in New Zealand and Australia: www.beyondblue.org.au/index.aspx?link_id=94

In considering the use of either tool for screening by LMCs at six weeks, White concludes that the EPNDS ‘may be an efficient method of screening for normal adjustment versus symptoms of PND’ (White 2008, p 19). White conceded that both tools are developed for the ‘western’ paradigm and that Indigenous peoples (Pacific Islanders, Māori, Australian Aborigines) need to develop screening tools of their own (White 2008).

It is expected that the issue of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) would be on the midwife’s agenda, in appropriate cases, long before the six-week discharge. However, should the midwife believe that the woman may have consequences at a later time but at six weeks responds blankly, neutrally or negatively to professionally sensitive probing, the ‘Troubled by your birth experience’ pamphlet issued by the Trauma and Birth Stress Organisation (TABS; see Online resources) may be accepted on the basis of it being a useful future reference and self-help/monitor check. The organisation Beyond Blue in Australia provides a number of resources for women suffering from postnatal depression, as do all state and territory health departments, many of which also provide help lines. (See also Chapter 40.)

Spiritual health

Supporting the woman’s spiritual needs requires a carefully accrued knowledge of the woman and her pregnancy, childbirth and early parenting journey, and actively listening to her reflections. Some women can articulate these clearly; others require gentle, persistent delving if the midwife detects spiritual pain. You might not feel qualified to support the woman in spiritual difficulty. Rather, your role might be to involve the woman’s own spiritual guides through her family.

Sexual health

it. Sensitive questioning may help elicit other sexual-health-related concerns and lead to a discussion about lack of desire. Several factors, such as a difficult birth, lochial discharge, tender secreting breasts, sore nipples, lowered levels of androgen and oestrogen, particularly in the first six weeks, are associated with vaginal dryness and lowered libido, altered physical appearance (some women may never have considered that the appearance of their genitals might be permanently changed), or fear of becoming pregnant again, and these can combine to depress the woman’s interest in intercourse. Breastfeeding also has an effect: ‘Although there are some physiological similarities between sexual arousal and breastfeeding, erotic stimulation and/or orgasm do not usually accompany breastfeeding. The hormonal basis of breastfeeding usually causes the woman to “fall in love” with her baby, thereby ensuring that she will respond to its needs’ (Auckland Homebirth Association 1993, p 139). Exhaustion, changes in libido, deterioration in general understanding and communication between the couple can all develop, whether or not there is discomfort. It is beginning to be understood that such difficulties are common. A wide range of feelings is normal (Dixon et al 2000; Force 2000). The woman may need advice about a lubricant; she may need support to foster open, frank communication with her partner.

Cultural health

Like spiritual health, cultural health is often less than ideally attended to by healthcare professionals in both Australia and New Zealand. In New Zealand, healthcare professionals are expected to develop and meet standards of cultural competence (Health Practitioners Competence Assurance Act 2003) and midwifery has embraced the frameworks of cultural safety, midwifery partnership und Tūranga Kaupapa as outlined in Chapter 16. The capacity of the midwife to acknowledge a culture that may be different from the dominant culture yet clearly potentially influential on the health status of her client is to be carefully nurtured. Australia and New Zealand both claim multicultural communities. However, in both, the dominant ethnic group has been Anglo-Saxon. This power imbalance between the groups requires constant vigilance in order not to abuse it.

At six weeks it is late in the day to begin assessment. Ideally the midwife will already have incorporated, within her holistic approach, attention to the language, customs, culturally sensitive aspects and safety measures relevant to her client and the family. These efforts will enable her now to seek valid feedback from her client. A midwifery ‘wisdom’ developing in New Zealand, at least, is the importance of regarding each pregnant woman as having her own unique culture. This approach is inherent in both cultural safety and midwifery partnership as described in Chapter 16. If this approach were adopted as standard within midwifery practice, then the woman’s safety, with regard to her wider ethnic cultural needs, would be assured of the necessary attention and respect.

Box 33.3 Breastfeeding resources

Is the woman aware of all the community-based breastfeeding resources available to her, such as:

Physical assessment

The six-week check is so-timed as it is known that the endometrium is fully healed by six weeks (Fraser & Cooper 2003; Henderson & Macdonald 2004). Ideally, your timing management of this physical check for the mother will ensure that this is attended to prior to the baby waking/being woken. Much can be discussed during this one-to-one opportunity with the woman. Wider personal and public health information can be passed on (diet, exercise, smoking, cervical screening), and final questions asked, such as:

• Does she have any concerns regarding her breasts and nipples?

• If there is a caesarean scar and if she chooses midwife discharge assessment (as opposed to returning for an obstetrician clinic appointment), how well healed is this scar?

• You should find the uterus completely involuted and not palpable abdominally.

• Has her bleeding stopped? In New Zealand, funding for a scan of the uterus to detect retained products is part of the LMC budget only until six weeks postpartum. Ongoing lochial discharge, suggestive of non-involuted uterus and some retention of

Clinical point

Continuity and perineal care

In her recent review of midwives’ approaches to care of the perineum, Wickham noted (while commenting on another study) that: ‘midwives were able to reflect upon their practice in relation to the woman’s experience, something which midwives working in systems without continuity of partnership are not often given the opportunity to do’ (Wickham 2001, p S26). Those midwives were then able to alter their practice significantly.

membrane or other placental fragment, could be assessed at five weeks and an appropriate scan ordered with consent, to avoid the woman/couple sustaining the cost. However, studies suggest that ongoing loss up to 42 days is not unusual (Marchant et al 2002; Wickham 2001), and a decision regarding a scan may best be held over until 8 or 10 weeks and require general practitioner (GP) referral. Obviously the budget issue does not affect Australian midwives, and advice by them to see their GP at the more reasonable time of eight weeks with ongoing, non-period bleeding would suffice.

• If there is bleeding, is it lochial or menstrual? (See Chapter 28 for physiology of the puerperium.)

• If there has been any perineal, vaginal wall or labial damage (sutured or not), the area should be assessed for degree of healing. Use a good light, and gloved hands. If she has not done so already, the woman should be encouraged to look in a mirror herself to know how differently her genital area now appears.

Box 33.4 Family violence prevention

Do you know the process of documenting your concerns and conveying them to the appropriate agency?

Does your College of Midwives have best practice guidelines for your response in these situations?

New Zealand midwives can view the NZCOM Consensus Statement on family violence screening at: www.midwife.org.nz/content/documents/93/family%20violence.2002.doc.

The question of dyspareunia is a natural one to arise now (see Ch 27). The appropriateness of pelvic examination, cervical smear and vaginal swabbing to take place during this examination is dealt with elsewhere in this book (Ch 27). Do not overlook the state of the anus and the

Critical thinking exercise

Research and plan approaches to the following topics as part of your discharge visits:

presence of haemorrhoids. Ask directly about urinary, faecal and flatus incontinence (O’Connell 1997). It is most appropriate to follow up now on your earlier explanation of pelvic floor exercises (see Ch 27). Does she understand how, why and when?

Family violence screening

Family or domestic violence is a complex issue that spans all socioeconomic strata. Questions regarding abuse should be included in all clinical assessments and by all practitioners (Hedin 2000, cited in MIDIRS 2000). New Zealand LMCs and Australian midwives, who are trained to screen for family violence, screen women at booking, again in the second and third trimesters, and at discharge (see Ch 7).

Indicators of possible family violence are:

THE BABY’S HEALTH

As you assess baby, note her or his social development and how the mother/parents relate to the baby—that is, continue your assessment of the holistic health of the mother as you interact with the baby. You should also seek and flag any ongoing information needs, including what developments would cause the mother to seek medical attention (see Ch 30).

Feeding and behaviour patterns

Breastfeeding

• Is breastfeeding going as well as the woman expects?

• Is the baby having yellow, paste-consistency stools?

• How many wet napkins are there in 24 hours?

There might be no discernible pattern yet to the baby’s sleeping and feeding behaviour. This may or may not be a concern for the mother/parents. Stress how normal it is for there to be no pattern despite popular expectations of babies quickly establishing a routine of sleeping and feeding (Gainsford 1999; St James-Roberts 2006). Fatigue will generally be the outstanding physical symptom for the mother, and it is not too late to discuss ways in which she can manage her sleep/rest needs, alongside co-sleeping information (see Ch 30).