Web Resource 7.1: Pre-Test Questions

Before starting this chapter, it is recommended that you visit the accompanying website and complete the pre-test questions. This will help you to identify any gaps in your knowledge and reinforce the elements that you already know.

Learning outcomes

On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

- Differentiate between the concepts of competence and capability

- Explain what is meant by interprofessional learning

- Examine the development of interprofessional capability in terms of student learning

- Analyse the practice of interprofessional capability in the context of safeguarding children

Competence and Capability

For well over a decade literature has argued and debated the relative merits of ‘competence’ and ‘capability’. This discussion has been particularly charged in the context of vocational education, with competence and capability even being described as being in competition with each other, although neither has gained priority over the other (Berman Brown and McCartney 2003). Nevertheless, in the context of health- and social care education, the notion of ‘competence’, and its measurement, appear to have a privileged place. The General Medical Council (GMC 2007, 2009, 2010) refers to undergraduate, pre-registration and practising doctors needing to meet mandatory competencies in order to qualify and continue practising in medicine. The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC 2010) has recently revised the required outcomes for nursing and midwifery pre-registration education. Again, this is couched in terms of the achievement of mandatory competencies which decide whether a student is competent, or not, to practise as a nurse or midwife.

The General Social Care Council (GSCC) does not refer directly to competencies as an outcome of education, but identifies mandatory standards. These standards are, however, explicitly related to competence. In their document Standards for the Award of the Social Work Degree (GSCC 2002, p 9), the specified standards are referred to as forming ‘the basis of the assessment of competence in practice’, and in the Post Qualifying Framework (GSCC 2005) it is indicated at all levels that practitioners are required to demonstrate competence. The Health Professions Council (HPC), into which it is intended the GSCC will be incorporated, also refers to standards of proficiency as an outcome and continuing requirement for qualified practice (HPC 2009). However, there is a clear link to competence. The ability to meet and maintain the specified standards of proficiency is associated with continued competence. Lack of competence raises questions about continued fitness to practise (HPC 2010).

As stated previously, ‘capability’ is frequently mentioned in health- and social care education, particularly in multidisciplinary contexts. Examples of its use can be found in the sphere of mental health in the documents The Capable Practitioner (Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health or SCMH 2001) and The Ten Essential Shared Capabilities (Department of Health or DH 2004c), in interprofessional education in the document The Interprofessional Capability Framework (Gordon and Walsh 2005) and in cancer care in the document Working with Individuals with Cancer, their Families and Carers (NHS Education for Scotland or NES 2005). Capability is also a concept under discussion within social work education developments. However, it is interesting to consider why the demonstration of competence, rather than capability, appears so prevalent.

Activity 7.1

- What do you understand by the term ‘competency’?

- What do you understand by the term ‘capability’?

- What is difference between these two terms?

Competence

‘Competence’ can be seen as an indicator of the end-point of learning and may be one explanation as to why it has such a high profile. It can be defined as ‘the capacity to deal adequately with a subject or task … to be suitable, fit, appropriate and proper’ (Berman Brown and McCartney 2003, p 7). Accepting this definition in the context of health- and social care leads to a natural conclusion that competence is required for individuals to be able to operate effectively within these services. Ensuring that the emerging workforce is ‘fit’ points to notions that this ‘fitness’ needs to be judged and assured – leading to the need for measurement. This is where competency frameworks come into their own. Competencies refer to the behaviours that should be demonstrated to show that a job is being undertaken effectively (Woodruffe 1993). It is this aspect of defining competence that has become prevalent and carries an emphasis on testing and assessing observable behaviours in terms of performing tasks and elements of ‘jobs’.

Perhaps the most illustrative (or extreme) examples of competency-based frameworks are those found in the National Vocational Qualification (NVQ) and Scottish Vocational Qualification (SVQ) frameworks, where each aspect of a job is broken into small elements or tasks. These are referred to as ‘units of competence’ which are couched in observable or measurable terms of skills and knowledge in order to be assessed. The worker is then judged to be ‘competent’ or ‘not yet competent’ when assessed against specific criteria. This is no simple task because many aspects of jobs need to be broken down into assessable components. Even informative material for prospective students acknowledges the detailed, prescriptive nature of these frameworks: ‘SVQ can seem tedious, e.g. writing down in detail the process you take to do a task’ (see Lifetracks.com at www.lifetracks.com/learning/qualifications/types-of-qualification/svq).

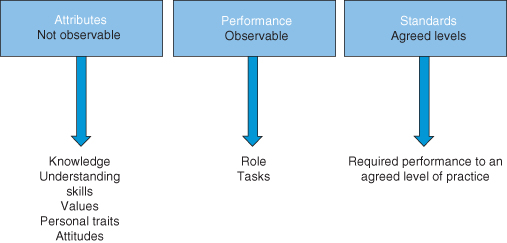

From the discussion above, it can be seen that the competence model can be challenged on the basis that many of its conceptualisations focus on the performance of the task (Heron and Murray 2004). This challenge is particularly apt when referring to work that is argued as being ‘higher order’ (such as healthcare and social work/care professional practice). Working in these areas requires practitioners to draw on abilities such as psychomotor skill performance and professional judgement. Wilson and Holt (2001) have argued that concentrating only on ‘competence’ may not be sufficient to prepare practitioners to respond effectively to the challenge of professional practice. Hagar and Gonczi (1996) agree, stating that care activities will become fragmented and professional practice reduced to a series of observable tasks. Boyastzis (1982) points out that educationalists are measuring the outcome of tasks based on performance alone and this is a cause for concern. Gonczi et al (1993) describe competence as having three components: attributes, performance and standards (Figure 7.1).

Web Resources

Web Resources

7.2a: Case Study

7.2b: Competency and Capability

To gain further understanding visit the accompanying web page which illustrates the three components with a case study.

Capability

Fraser and Greenhalgh (2001) have argued that competence involves what individuals know or are able to do, whereas capability refers to the extent to which a person can apply, adapt and synthesise new knowledge from experience and continue to improve performance. Definitions such as these support claims that capability, rather than competence, better reflects the requirements for professional practice. Wilson and Holt (2001) highlight the differentiations between the two terms, which indicate that capability accommodates the intricacy and ambiguity of professional work more effectively. Earlier definitions of competency are related to definitions of capability. Stephenson (1998), for example, indicates that capability is ‘an integration of knowledge, skills, personal qualities and understanding used appropriately and effectively’. This is similar to Boyastzis’s (1982) ideas of competence, which includes personal characteristics that contribute to a worker’s effectiveness.

Fraser and Greenhalgh (2001) suggest that capability incorporates competence. Their view of capability includes the successful demonstration of tasks, the performance of which evolves as practice changes. This notion of responsiveness to change is reflected in the NHS Education for Scotland and Macmillan Cancer Care’s (NES 2010, p 6) development of a continuing development framework for people working in the context of cancer care. This work indicated that capability frameworks focus on:

- realising individuals’ full potential – Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (see Chapter 9)

- developing the ability to adapt and apply knowledge and skills – mentor’s role (see Chapter 2)

- learning from experience – experiential learning and reflective practice

- envisaging the future and contributing to making it happen – career progression (see Chapter 9).

The notion of the performance of ‘task’ is also seen in the work of the SCMH (2001, p 2) which reports ‘capability’ as having the following dimensions:

- A performance component that identifies ‘what people need to possess’ and ‘what they need to achieve’ in the workplace. (This links to Gonczi et al’s (1993) components of competence, attributes, performance and standards.)

- An ethical component that is concerned with integrating knowledge of culture, values and social awareness into professional practice. (This links to Gonczi et al’s (1993) component of attributes.)

- A component that emphasises reflective practice in action. (This links to Gonczi et al’s (1993) components of competence, attributes and performance.)

- The capability to effectively implement evidence-based interventions in the service configurations of a modern mental health system. (This links to Gonczi et al’s (1993) components of competence, performance and standards.)

- A commitment to working with new models of professional practice and responsibility for life-long learning. (This links to Gonczi et al’s [1993] components of competence, attributes, performance and standards.)

Activity 7.2

From what you have read so far, how do you differentiate between a competence and a capability? In a few sentences, write out what you perceive to be the key difference between these two concepts.

Consider your own practice in supporting students. Which concept assists you best in considering what they need to learn? Identify why you have selected one or other of them.

Berman Brown and McCartney (2003, p 9) offer further differentiations between competence and capability. They claim that issues of ‘potential’ and ‘time’ are important in considering these matters. The demonstration of competence, in their terms, looks back to a successful demonstration. This indicates that the successful performance of a task already mastered indicates competence, whereas a capability ‘looks forward to the fulfilment of potential’. They go on to suggest that capability relates to having the ‘needed capacity, power or fitness for some specified purpose or activity’. The notion of having potential to be able to act in ways that will be required in the future brings in a notion of time. Time, according to Berman Brown and McCartney (2003), is both the strength and the weakness of capability – weakness in terms of the focus on potential to perform rather than proven performance (but once proven becomes competence), but strength in that, rather than being a static, time-bound concept, capability implies possibility, growth and development.

It can be argued, therefore, that capability’s strengths of encompassing complexity and potential are well fitted to guide professional development. Its weakness of ‘future time value’ (Berman Brown and McCartney 2003, p 10) refers to its inability to be predefined and thus assessed. However, this can be accommodated by the notion of when the potential is achieved, becomes concrete and emerges as competence and part of capability. The remainder of this chapter explores capability in terms of interprofessional education and practice – a complex, ambiguous and multifaceted field that it can be argued capability is well placed to address (Barr 2002).

Interprofessional Education and Practice

Interprofessional education is defined by the Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education (CAIPE 2002) as occurring ‘when two or more professions learn with, from and about each other to improve collaboration and the quality of care’. It started to emerge in the UK during the 1960s, developing as the reforms of health- and social care post-World War II illuminated failures in collaboration between professions. These failures threatened the integrity of the new ‘Welfare State’ (Barr 2002). The development of interprofessional education increased during the 1970s to the present day, as successive public enquiries and scandals drew more and more attention to collaborative breakdown within and between services. The finger of blame often pointed towards the lack of cooperation and communication among individuals, professions, agencies and organisations (see Kennedy 2001 and Laming 2003, for example). Later in this chapter we examine this phenomenon through the concept of child protection or safeguarding.

Interprofessional education, despite its adoption into UK higher education policy with respect to the preparation of health- and social care/work professionals, remains a contested concept. This can be explained on several levels, including professional rivalry and dispute (Bechter and Trowler 2001), the perceived lack of evidence that interprofessional education leads to improved collaborative practice, and conceptual muddying of what interprofessional education actually is. However, this sceptiscm has been challenged somewhat by the recent World Health Organization (WHO 2010) report. This report asserts that there is now enough evidence to conclude that the only way workers can effectively engage in collaborative practice is through participating in interprofessional education.

Other difficulties around the delivery and understanding of interprofessional education concern how it is defined. As indicated at the start of this section, interprofessional education should refer to learning events that have the focus and aim of improving collaboration between two or more professions. However, there is frequent misunderstanding on this issue, with assumptions that putting mixed professional groups of students together to learn the same thing equates to interprofessional education. The accepted CAIPE (2002, p 6) definition of multiprofessional education being ‘occasions when two or more professions learn side by side for whatever reason’ helps to discriminate between the two concepts. Similarly shared learning can be understood to be the same as multiprofessional education. Early examples of what was called interprofessional learning often involved interventions based on economic and logistic expediency, e.g. students from several health courses that all had biological science elements could be brought together to learn that topic. These strategies resulted in variable levels of success, but any outcome of students gaining greater understanding of each other’s roles or being able to communicate and collaborate better were more by accident than by design.

Contrasting with the object of learning that one might see with multiprofessional or shared learning sessions that centre on the ‘subject’ or ‘topic’ in question, Barr (1998) suggested over a decade ago that learning outcomes of interprofessional education should focus on collaboration and working effectively with others:

- Describe one’s roles and responsibilities clearly to other professions and discharge them to the satisfaction of those others

- Recognise and observe the constraints of one’s role, responsibilities and competence

- Recognise and respect the roles, responsibilities and competence of other professions in relation to one’s own, knowing when, where and how to involve those others through agreed channels

- Work with other professions to review services, effect change, improve standards, solve problems and resolve conflict in the provision of care and treatment

- Work with other professions to assess, plan, provide and review care for individual patients and support carers

- Tolerate differences, misunderstandings, ambiguities, shortcomings and unilateral change in other professions

- Facilitate interprofessional case conferences, meetings, team working and networking.

Activity 7.3

Think about when you have been involved in teaching/learning situations with learners from more than one profession.

- How would you describe the learning? Was it multiprofessional or interprofessional?

- What were the characteristics of the session that led you to this conclusion?

Interestingly, in light of what has already been discussed in this chapter, Barr referred to competency-based models when devising the aims and outcomes of interprofessional education above. In his later work, however, he began to argue that capability, rather than competence, better recognises the many-layered and multiple processes that professionals are expected to perform (Barr 2002). The next section describes the development of an Interprofessional Capability Framework that aims to guide students and those who support their learning in their development as collaborative workers.

The Interprofessional Capability Framework

The Interprofessional Capability Framework was first devised as part of the work of the Combined Universities Interprofessional Learning Unit (CUILU), a collaborative project between the University of Sheffield and Sheffield Hallam University. The Framework was developed through analysis of the Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA) benchmark statements (QAA 2000, 2001, 2002a) relating to undergraduate programmes of medicine, dentistry and the professions allied to medicine, including nursing, midwifery and social work. It was validated for practical implementation through interviews with students and practitioners who supported and assessed students’ learning in practice (see Gordon et al 2004, Gordon and Walsh 2005 and Walsh et al 2005 for detail). In 2010 a revised version (Sheffield Hallam University or SHU 2010) was developed through further analysis of relevant documents relating to collaborative working published since 2004, and use of a Delphi method (Dalkey and Helmer 1963) to elicit expert opinion on the validity of the Framework.

The revised version, similar to the original version, contains statements of capability in terms of what might be expected in qualified practice, with staged learning levels (that could be thought of as competencies) leading to each capability. The capabilities and their associated competencies are grouped in domains that are aspects of collaborative practice. In the revised version (SHU 2010, p 6), these domains are as follows.

Collaborative working (CW) captures working in partnership with people using services and other members of the community of practice. It emphasises the importance of the collaborative worker utilising interpersonal skills to promote effective communication; this leads to shared decision-making regarding the setting and achieving of mutually agreed goals.

The reflection (R) domain highlights the importance of reflective capability in promoting critical self-awareness in members of the community of practice. It emphasises the process of reflection as a means to inform personal and continuing professional development in individuals, and how this contributes to the development of effective collaborative working between members of the community of practice.

The cultural awareness and ethical practice (CAEP) domain relates to the promotion of cultural awareness in collaborative workers when engaging with people who use services. It reflects the need to take responsibility for personal and professional development of cultural sensitivity in working with people who use services to promote their informed participation in decision-making. It also underlines the importance of members of the community of practice being aware of the demands made in law of the other professions, with regard to their duty of care, and responsive to the underpinning ethos of the different professional groups.

The organisational competence (OC) domain recognises the importance of a critical understanding of the policy context for collaborative working across both professional and organisational boundaries. It focuses on the capabilities required of the collaborative worker to participate and take a lead in promoting effective partnerships – partnerships between people who use services and members of the community of practice, and wider collaborative partnerships across different organisations – to produce the desired outcomes.

The complete framework can be accessed online at: www.cuilu.group.shef.ac.uk/documents.htm.

The PowerPoint presentation ‘Interprofessional Mentorship, what is it and how do we do it?’ by Dr Michelle Marshall can be accessed via www.cuilu.group.shef.ac.uk/Interprofessional_Mentorship.ppt.

Activity 7.4

Consider the domains of collaborative working described above. How far do these descriptions resonate with your own experience of practising, learning and/or teaching collaborative practice?

How might you use the Framework when supporting students’ development as collaborative workers?

In the next section we consider the concept of child safeguarding or protection, an issue that relies on collaborative practice among individuals, organisations and agencies, and how the Interprofessional Capability Framework could be employed to support collaborative learning and working in that context.

An Analysis of the Practice Utility of Interprofessional Capability in the Context of Child Safeguarding or Protection

This section explores the usefulness of interprofessional capability when thinking about effective child protection. We first consider the national policy and practice context of child protection (or safeguarding) and interprofessional collaboration. Second, we explore what a model of capability offers individual professionals, referred to also as members of the community of practice (Wenger 1998), who are responsible for safeguarding children. We also consider what a model of interprofessional capability offers to child protection practitioners working across agency, or organisational boundaries. Finally, we use a case study to illustrate how such a model of capability could impact on the way professionals and agencies, within the community of child protection practice, work together to safeguard children.

The Policy and Practice Context of Child Protection (or Safeguarding) and Interprofessional Collaboration

Research has shown that families of children who suffer serious harm, or die at the hands of their carers, are often characterised as chaotic, with unpredictable behaviour, and presenting varied levels of engagement with agencies (Vincent et al 2007; Brandon et al 2008a; Laming 2009; Ofsted 2009; Munro 2010). Such families present real challenges to professionals, and other members of the community of practice, who are trying to work with them to protect the child, or children, concerned. The term ‘community of practice’ is used by Wenger (2006) to describe the range of individuals, and agencies that may be involved in providing services. It is a useful idea when thinking about interprofessional practice in child protection. Wenger’s idea of a community of practice is a group of professionals from a shared domain of interest (in this example, the domain of child protection), who engage in joint working to develop positive relationships, and learn from each other (e.g. through sharing information). Over time, and through commitment, this group of practitioners develop what Wenger describes as ‘shared practice’, or a ‘repertoire of knowledge’, which enhances the quality of their work together (Wenger 2006). This seems an apt description of what collaborative working should be – certainly what it is intended to achieve.

The ‘community of child protection practice’ consists of a number of different agencies and professionals, involved with vulnerable children and families, from both universal and specialist services, such as social workers, nurses, teachers, general practitioners, hospital consultants and mental health professionals. In safeguarding children, this network of individuals and agencies is required to engage with the child in the context of chaotic and often complex family relationships. The research evidence repeatedly documents how this environment can be mirrored in the thinking and actions of professionals, and interactions between agencies (for a particularly clear account of this, see Brandon et al (2008b, p 39). Such confusion can result in significant failures in communication between individuals, and across agencies, with an attendant increase in the risk to the child, or children. The research evidence identifies a number of consistent themes across the UK in respect of the failings, or shortcomings, in child protection practices; these themes include problems of information sharing and of accountability, with professionals failing to realise their responsibility for child protection (Brandon et al 1999, 2002, 2008a,b; Scottish Executive 2003; Munro 2004, 2010; Vincent et al 2007; Laming 2009).

Child protection, or safeguarding, is an area of practice that requires significant capability in collaborative working between different agencies. It is an aspect of practice that has attracted significant publicity in the media, following reports on a number of high-profile failings in interagency working where children have died, such as in the cases of Victoria Climbié, in 2003, Kennedy Macfarlane, in 2003, and Peter Connelly, in 2007 (‘Baby Peter’). The details of agency failings have been reported in the media, particularly the shortcomings of social workers or Social Services (or Children’s Departments as they are known in England). The publicity surrounding such high-profile child deaths has, predictably, led to calls for more regulation of social work in particular, but also other child welfare agencies, including health and education professionals. It is acknowledged that effective collaboration between individuals and agencies in child protection remains hard to achieve, and the complexity of child safeguarding defies simple solutions (Laming 2009; Munro 2010). However, in detailed evaluations of serious case reviews into child deaths over the past 30 years, there is repeated evidence of system and practice failings, including ‘deficits in inter-agency working, collecting and interpreting information, decision making, and in aspects of relations with families’ (Brandon et al 2008a, p 9). The social work profession is seriously implicated in these findings, and there is evidence from child protection research to show that there is a correlation between the effective engagement of social workers with a family, and improved outcomes for a child:

Where social work performed well outcomes were generally good and when they performed less well outcomes were generally poor. Although good outcomes were assisted by the work of all agencies they were less dependent on other agencies.

Scottish Executive 2003, p 11

The input of social workers is key to effective child protection, but sufficient resources may not be forthcoming: ‘the social worker is always faced with discerning the priority case from among the many which are in need but will have to manage with a lesser service or not at all’ (Haringey Local Safeguarding Children Board 2009a, p 10). However, the role of universal services is also key in child protection, and health, social care and education agencies at both specialist and universal service levels share the responsibility in many cases of child deaths; indeed, more than half non-accidental deaths ‘take place in the care of universal services without referral to the child protection system’ (Haringey Local Safeguarding Children Board 2009a, p 10). Lord Laming’s report into the failings that led to the death of Victoria Climbié (DH 2004a) identified the significance of common processes across all agencies involved with providing social care for vulnerable children and their families, and the importance of effective interagency working to safeguard children. This view has been echoed in subsequent reviews into child deaths in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland (see Hammond 2001; Scottish Executive 2003; DHSSPS 2006; Vincent et al 2007, among others).

Over the past decade the publishing of reports into child deaths (these ‘reports’ are variously termed ‘serious case reviews’ or ‘child death reviews’) has triggered wider reviews of children’s services across the UK (see Scottish Executive 2003; Department of Health or DH 2004a; Brandon et al 2002; DHSSPS 2006; Laming 2009). In Scotland, the report into the death of Kennedy Macfarlane, who was killed by her mother’s partner, concluded that poor practice, both clinical and professional, together with interagency failings in communication had contributed to the death of the child (Hammond 2001). Following a number of serious case review reports into high-profile child abuse cases in Wales, the system of reporting on, and learning lessons from, cases of children suffering serious harm or death is to be reviewed (a child death review pilot study has been set up in 2010), and the Northern Ireland Office initiated a review of child protection services in 2006 (DHSSPS 2006).

A number of key policies, and practice guidance for safeguarding and promoting the welfare of children, emerged in the aftermath of these reviews. In England and Wales, the interagency agenda was taken forward through the Green Paper Every Child Matters (DH 2003), which led to the Every Child Matters ‘Change for Children’ programme (DH 2004b), and via practice guidance such as Guidance Working Together to Safeguard Children (DfCFS 2006), Safeguarding Children: Working together under the Children Act 2004 (Welsh Assembly Government 2005), and All Wales Child Protection Procedures (All Wales Child Protection Procedures Review 2008). In Scotland, following the review of child protection (Scottish Executive 2003) the Children’s Charter has been introduced (Scottish Executive 2006).

National legislation governing the protection of children (such as the Children Act 1998 and the Children (Scotland) Act 1995) has also been reviewed in the light of high-profile child deaths, to emphasise the need for effective multiagency working across children’s services. For example, in England after Lord Laming’s report into the death of Victoria Climbié (DH 2004a), the Children Act 1998 was amended (the Children Act 2004) to require interagency working of health, education and social children’s care services through the setting up of Local Safeguarding Children Boards, and Children and Young People’s Strategic Partnerships (or Trusts). The Partnership agencies with responsibility for services to children have, since 2005, been required by law to implement S11 of the Children Act 2004, thereby becoming safeguarding agencies. A similar revision was made to child protection legislation in Scotland at the same time, to enshrine the importance of multiagency working across local authorities: the Protection of Children (Scotland) Act 2003.

Safeguarding is something that requires a multiagency approach. Identifying and responding to child abuse and neglect are not the preserve of any one agency, but where a child protection issue has been identified, social workers are centrally responsible for assessment and intervention. A significant consequence of the high-profile examples of perceived failures of social workers to safeguard children in the past 5 years has been a full, organisational review of the profession, including redefining the purpose of social work, and revising the structures for training social workers. This review of the social work profession was called for by the then Labour government’s Children’s Minister, Mr Ed Balls, in 2009, after the publication of the first serious case review into Baby Peter’s death. This led to the setting up of a Social Work Task Force to undertake the review, and report back to the government. The Task Force published its findings in 2009 (Social Work Task Force 2009), and on the basis of this report the Social Work Reform Board set out a programme of proposed reforms to social work training and practice. Alongside this, Lord Laming was asked by the Minister to prepare a further report on the state of children’s services in England (Laming 2009) to report back to the Social Work Task Force.

Evidence submitted to Lord Laming’s progress report (Laming 2009) to the Social Work Task Force on child protection services in England has been used to inform a far-reaching review of child protection services under the guidance of Professor Eileen Munro, the first part of which was published in 2010 (Munro 2010). The Munro report is being compiled in the context of a range of reviews of child protection services across the UK (see above), and following calls for wider evidence on child protection from frontline practitioners, leaders, policy-makers and service users in England. Evidence to emerge in the first part of the report indicates inconsistencies and uncertainty among professionals, when working across agency boundaries, over referrals and contacts about vulnerable children and young people. Also the report highlights a significant increase in reliance of frontline professionals on technical solutions to problems of interagency working, to the detriment of the children and families being worked with (Munro 2010).

The Munro review provides evidence of how an emphasis on technical solutions to problems of failures in working together results in an over-reliance on, or compliance with, regulation and procedures, at the expense of social workers spending time with children and families. This shift to more managerial working practices further reduces the scope for professionals to exercise critical judgements on complex matters of risk. The report finds that the performance and inspection regime does not adequately provide information about the quality of direct work with children and families, and professionals such as social workers are required to spend too much time inputting data onto information and communication technology (ICT) systems, as part of the Integrated Children’s System (ICS) (see also Cleaver et al 2008). The ICS is seen as key to the delivery of the Every Child Matters agenda outcomes for the most vulnerable children. The ICS has been implemented across England and Wales, and is intended to improve outcomes for children through provision of a common conceptual framework for assessment, intervention and review of services for vulnerable children and families, to be used by all providers of children’s social care. Munro’s concern is echoed by others, including Lord Laming (2009, p 32).

So, despite the efforts of previous governments to introduce reforms in the protection of vulnerable children, these reforms have not led to the anticipated improvements in practice, but rather have apparently made things more difficult. Munro (2010, p 5) suggests that ‘there is a substantial body of evidence indicating that past reforms are creating new, unforeseen complications’. Whatever the view on previous reforms, there is recognition among policy-makers and practitioners involved in child protection that current practice has become over-standardised and unable to ‘respond adequately to the varied range of children’s needs’ (Munro 2010, p 5). In the context of these challenges we focus on the process of how individuals and agencies can make use of interprofessional capabilities to collaborate effectively in safeguarding children.

Activity 7.5

- Are you aware of the policies and procedures for interagency working to protect children that inform your practice with members of the community of practice?

- Can you identify where reviews of child deaths have led to changes to working practices in your agency?

- In the light of this, how can you facilitate learning opportunities around policy and legislation for interagency working in child protection for the students on placement with your agency?

- What can a model of interprofessional capability offer to child protection practitioners working across agency or organisational boundaries?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree