CHAPTER 5 Community action for social and environmental change

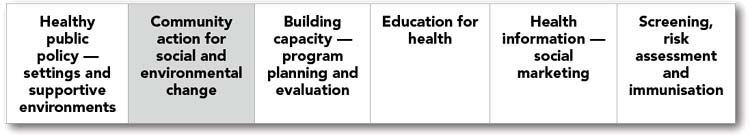

In Chapter 1 the continuum of health promotion approaches was introduced. In this chapter we will move along the health promotion continuum from developing healthy public policy to create supportive environments, to ‘community action for social and environmental change’.

CHANGE IN COMMUNITIES

In community-level work the environment, rather than the individual, is the focus of change (Labonté 1986: 347). Working with communities to bring about a desired change to improve health in the community can be achieved using ‘bottom-up’ or ‘top-down’ approaches or a mixture of both. There are many theories that guide health workers in understanding how change occurs in communities. We have selected three that are generally familiar to health promotion workers: diffusion of innovation; community organisation; and community building or development. Put simply, diffusion of innovation theory provides us with an understanding of how new ideas are introduced and adopted in a community. The change process can be introduced from the community (‘bottom-up’) or from institutions (‘top-down’). Community organisation theory provides understanding about how organisations and health workers bring about change in local communities. This is a ‘top-down’ approach where organisations with power to direct policy and implement change identify priorities outside the context of the community. Workers with expertise and knowledge about a population develop policies and programs aimed at improving the lives of vulnerable groups without necessarily including members of those groups in the decision-making processes. Community development approaches help us to understand the ‘bottom-up’ approaches to change where communities are central in the identification of priorities and decision-making about their future. This ‘bottom-up’ approach is driven from the grass roots of the community. These theories are contested and each continues to evolve.

Working with the community has the potential to address some of the structural issues, specifically at the local level, that lead to poor health. As we have said in Chapters 1 and 2, there are many factors that lead to poor health. The conditions in which people are born, live, work and age have a powerful influence on their health. Social factors create the life experiences and opportunities which in turn make it easier or more difficult for people to achieve optimal health. Equity of access to social and health resources is an important factor in determining health outcomes.

Using community development theory

The terms ‘community development’ and ‘community organisation’ are both defined variously and often overlap in their definition. While Minkler’s definition (1991) refers to community organisation, it actually describes community development. Rothman and Tropman (1987) described community development as one form of community organisation. Egger et al (2005: 134) have described the difference between the two terms as one of ‘directiveness’, because they regard community organisation as being a process more directed by workers, while community development is more directed by members of the community.

In Chapter 2 we noted that the term ‘community’ has different meanings. In community development, emphasis is placed on community as a social system, bound by geographical location or common interest, recognising that community is ‘a “living” organism with interactive webs of ties among organisations, neighbourhoods, families, and friends’ (Eng et al 1992: 1). Definitions of community commonly encompass elements of geography, culture and social stratification (Naidoo & Wills 2000). These three factors are viewed as bringing together people into a positive and desirable common entity (Naidoo & Wills 2000). However we also noted in Chapter 2 that communities are not necessarily homogenous entities; they often include groups with conflicting interests, and that this fact is often hidden behind the romantic connotations of the term ‘community’.

The notion of a ‘sense of community’ was also discussed in Chapter 2. This feeling is an ideal state in which everyone affected by the life of the community participates in community life. The community as a whole takes responsibility for its members and respect for the individuality of the members is maintained (Daly & Cobb 1989: 172). There is a ‘sense of solidarity and a sense of significance’ (Clark 1973: 409). This sense of community can be an important component of people feeling as though they belong to a community, and it also has implications for the process of community development (Falk & Kilpatrick 2000). Two further points are worth making here. Firstly, we need to take care not to oversimplify the consequences of human beings living in communities. Secondly, we must be careful not to assume that this sense of community is an ideal state for everyone, because some people may not choose living in a community as their ideal. These issues are of particular importance in considering community development, as these aspects of community may really come to the fore in the community development process. Indeed, workers using the community development process may have to regularly consider the implications of these issues in their work. Box 5.1 provides some ideals to work toward. Ife and Tesoriero (2006: 100) suggest that community is a subjective experience that means different things to different people; that communities evolve over time with ongoing dialogue, consciousness-raising and action.

BOX 5.1 Some principles of community

• A community is a group of people who share equal responsibility for and commitment to maintaining its spirit.

• A community is a highly effective working group.

• A community is the ideal consensual decision-making body.

• In community, a wide range of gifts and talents is celebrated.

• Individual differences are celebrated.

• Community facilitates healing.

(Source: Johnson K. In: Hoff M D 1998 Sustainable Community Development: Studies in Economic, Environmental, and Cultural Revitalization. Lewis Publishers, Boca Raton, Florida, pp 175–6)

Using diffusion of innovation theory

The diffusion of innovation theory provides us with a way of understanding how new ideas are taken up (or not); that is, how change takes place in a community (Rogers 1995). Diffusion is defined as the process by which an innovation is communicated through certain channels over time among members of a social system. An innovation is defined as an idea, practice, or object perceived as new by an individual or other unit of adoption (Rogers 1995). The process works in a group as clarity to a few, then gradual and later rapid uptake by the rest of the group. Five general factors that influence the speed and success with which new ideas are taken up have been identified: relative advantage; compatibility; complexity; trialability; and observability (Rogers 1995).

In theory the success or otherwise of innovation depends on how it is seen by various groups — whether the innovation is seen as compatible with the established culture, for example, or the perceived relative advantage of the innovation. The simplicity and flexibility of innovation together with its reversibility and the perceived risk of its adoption will affect the extent to which innovation is taken up by the community. Finally, the observability of results will influence whether others take up the change (Rogers 1995). An in-depth study of these factors and other theories may provide useful information for agents of change. The important thing is to know the community and what is likely to influence its response. Insight 5.1 demonstrates how this theory has been used to understand and track change in one community.

GOALS OF COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT

The concept of community development is complex, perhaps because the skills and activities that are required vary with the situation, and also because the outcome will be defined by the community and known only after the activity has commenced. It is difficult to bring ideal global visions of capable communities deciding their own courses of action down to practical, day-to-day achievable goals. However, it is important to have visions broader than meeting local objectives if real empowerment of the community is to be achieved and sustained.

INSIGHT 5.1 Community-wide education — Mount Alexander Sustainability Group

(Source: Mount Alexander Sustainability Group. Online. Available: http://masg.org.au/)

Community development work changes according to the needs of the community; it builds people’s skills for current issues and for the future. In the process it enhances their feelings of competence and personal self-esteem. It means their community is competent to adapt to future changes and that policy-makers will be more likely to consider their perspective in the future, and more accountable for their actions in the future.

1. Improvement of the quality of life through the resolution of shared problems. This may sound far too grand for a small community activity, but it may be as seemingly simple as having a local by-law changed so that trucks are prevented from carrying their uncovered loads of dusty mine tailings contaminated with arsenic, through residential areas. The potential for health enhancement by this action is clear.

2. Reduction in the level of social inequities caused by the social determinants of illness such as poverty. Actions may entail provision of transport for local people to attend community activities, but in order to make sustained change for a community, provision of access to services needs to be enshrined in the operational plans of service providers, rather than being provided on an ad hoc basis.

3. Exercise and enhance democratic principles, through peoples’ shared roles in decisions that affect them in their communities. Maintaining democratic principles, when it is easier and quicker to get on and do it oneself is one of the biggest challenges to health workers. The processes and skills outlined in the next sections provide more specific guidance for this goal.

4. Enabling people to achieve their potential as individuals. The involvement in community activity brings its own personal and non-tangible rewards, as well as the development of new knowledge and skills. At the outset of a program, these gains need to be acknowledged and documented in the objectives of the activity or project.

5. Creation of a sense of community. A strong cohesive and successful community will be powerful in creating the sense of belonging and ownership for its members. It is a means for people to achieve their vision.

A CONTINUUM OF COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT APPROACHES OR PRACTICE MODES

Community development is not one form of health promotion, or one style of activity or practice mode. The tasks involved in community development can be diverse, depending on the existing strengths, vulnerabilities and culture of the community of interest. What is consistent, and is set out in the definition of community development provided above, is the way of working; community development is a ‘bottom-up’ approach, that always involves working with a community, as they ‘steer’ the activity in their community. The worker must choose the way of working that best suits the needs and realities of the community they are working with.

1. the community’s identification of its own needs

2. the importance of the process as well as the outcome of the participation by community members in the community development process.

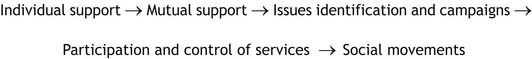

The community development continuum

People in times of crisis will have different needs for support than those who feel strong enough to take on policy-makers to bring about social change; therefore the role of the worker will differ accordingly. The continuum in Figure 5.1 gives some guidance to the role most suitable at the time.

FIGURE 5.1 The community development continuum

(Source: Adapted from Jackson T, Mitchell S, Wright M 1989 Community Health Studies, 13(1):66–73)

Individual support

In crisis situations community development workers assist families with everyday survival issues, because suffering is paralysing and incapacitating. Sometimes people are not in the position to think any more broadly than their day-to-day survival needs and it would be unethical not to address these as a first priority. However, in community development, workers need to nurture people’s abilities to take control over decisions rather than fostering their dependence on health workers. In Chapter 2 we refer to the ‘strengths perspective’ when working with individuals, and in Chapter 6 we refer to asset-based assessments when working in communities. These are conceptual models which enable us to describe the strengths of individuals and communities. Those working in the field of positive psychology, for example, advocate a change from focusing solely on repairing damage in individuals and families to one which includes ‘building the best qualities in life’ (Seligman 2002 in Jimerson et al 2004: 9).The role of the health worker, therefore, also involves supporting individuals with a ‘good’ idea; an idea that may benefit the wider community. Insight 5.3, the story of social transformation in Bromley-by-Bow in inner-city London (presented later in the chapter), provides a clear example of this principle being successfully implemented (Mawson 2008).

Participation and control of services

The key role at this stage on the continuum is one of empowerment of community members. Refer back to earlier discussions of empowerment and participation and to the discussion of Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation (1971) in Chapter 2, which emphasises the importance of true participation in decision-making and control of services rather than degrees of tokenism. At the beginning people tend to become involved in decision-making at a localised level to ensure that service provision meets their needs in activities such as neighbourhood houses or school councils. Community members are encouraged to view this local participation as a means of getting involved in wider social issues, not as an end in itself.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree