This chapter examines a variety of communication issues related to healthcare organizations, including communicative characteristics of organizations, types of healthcare organizations, and some of the major influences on communication within healthcare organizations in today’s healthcare system.

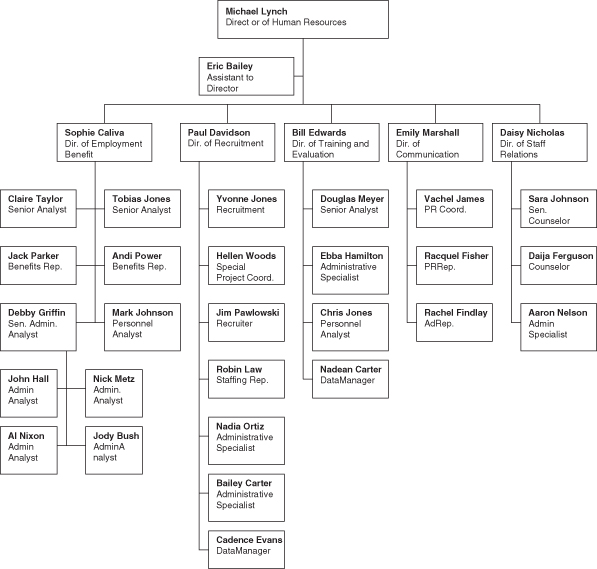

Figure 6.2 Health organizational hierarchy 2: Organizational chart from Oklahoma General Health Care Center.

Source: From the Office of Human Resources at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center: http://hr.ou.edu/. Reprinted with kind permission.

Healthcare Organizations as Systems

One helpful way to examine healthcare organizations is to view them as systems. O’Hair, Friedrich, and Dixon (2010) define a system as an interdependent collection of components that are related to one another and combine their relative strengths to respond to internal changes and external challenges. For example, a hospital can be viewed as a complex system that contains many smaller systems or interrelated units, such as the hospital’s administration, radiology department, and nursing department. In addition, hospitals are typically embedded within larger systems that oversee or influence the daily operations of the hospital (e.g. government agencies) or provide it with necessary resources, such as medical supplies (e.g. pharmaceutical companies).

The ways in which healthcare systems function have important implications for patient care. For example, a few years ago another dear friend of one of the authors was fighting fourth-stage esophageal cancer with a nearly three-inch malignant tumor that had metastasized to the liver. The surgeon at one hospital had told him to have the difficult and aggressive chemotherapy and radiation treatment to shrink the tumor down enough to do surgery. The surgeon said, “We can do it. It will be difficult, but if you do your part I can definitely get the tumor out of the esophageal area, move the stomach up and you will survive. The average survival rate is around five years, but you are younger and stronger than those statistics.” The surgeon continued to explain the ways in which the tumors have to shrink, particularly the ones in the liver, which may be more difficult depending on where they are located and how much they shrink from the chemotherapy and radiation, but he further expressed that “this operation is absolutely doable.” However, the “system” in which a surgeon operates may not be as optimistic about a patient’s prognosis due to the cost of such procedures. For example, the “system” at another hospital where the author’s friend obtained a “second opinion” told him to get his affairs in order, and that no chemotherapy or radiation would help. In fact, after a courageous fight he died about a year after his initial diagnosis. Both systemic opinions were correct, but coming from different perspectives and presenting the information in different ways. Many hospital administrators and other key decision-makers within healthcare systems often find they must focus on the bottom line, while patient care that is tailored to the individual rather than to the system can often take a back seat.

Characteristics of Systems

According to systems theory, systems have certain characteristics that can influence the communication behaviors of individuals within them. Complex systems such as healthcare organizations are more than the sum of their individual parts. Different units of a system are interdependent, and they interact in ways that create outcomes that would not be possible otherwise.

A hospital could not function if it relied only on the services of providers. A physician would have trouble diagnosing and treating a patient’s health problems if he or she did not have medical supplies or support from other units in the organization (e.g. nurses, technicians, laboratory personnel), a patient could not treat his or her health problem without the services of pharmacies and health insurance organizations, and the hospital itself could not exist without proper licensing from government health agencies and an administration that managed the business and legal aspects of the hospital (e.g. managing costs, ordering supplies, handling malpractice lawsuits). Each of these units (as well as many others) must work together and coordinate its actions for the hospital to function, and communication within and between different elements of the organization is vital to the organization’s ability to function effectively.

Systems have other qualities, such as homeostasis, or the ability of a system to self-regulate or achieve a sense of balance when faced with changing conditions. Similar to the thermostat in your home that adjusts to changing temperatures by turning on and off the heater or air conditioner, systems such as healthcare organizations must adapt to changing situations. For example, a normally busy medical clinic that finds itself with fewer patients than average for several months must advertise its services or make other arrangements to attract a suitable number of patients for the business to function. During the cold and flu season, a department of public health may need to take steps to insure a steady supply of flu shots to keep up with the increased demand. In both cases, the organizations are reacting to shifts in the system.

Systemic problems can be costly to health organizations. In fact, during the past decade there has been unprecedented national attention directed toward the safety of patients in hospitals. A “zero tolerance” approach has been put forward for certain healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) deemed preventable. Indeed, a sweeping alliance of professional organizations has fueled a national call to action to eliminate HAIs including the Institute of Medicine, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Infectious Diseases Society of America, Association of Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology, and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (Spellberg et al., 2008). This growing movement to protect patients from preventable infections is consistent with the proverbial adage of medicine, “primum non nocere.”

Generally, there is broad consensus that the burden of HAIs is unacceptably high. An estimated 1.4 million people worldwide have an HAI at any given time (Weinstein, 2008). In the US, there are approximately 2 million annual HAIs among newborns, children and adults that are responsible for nearly 100 000 deaths each year (Klevens, Edwards, & Richards, 2007). This ranks HAIs as the fifth leading cause of death in acute care hospitals (Klevens, Edwards, & Richards, 2007). Data suggest that 5 to 10 percent of hospitalized patients develop an HAI over the course of hospital admission (Weinstein, 2008). If these data are valid estimates today, the number of annual HAIs and attributable deaths may be even higher, given that there are 39.5 million hospitalizations in the US each year (Stewardson et al., 2011).

The financial burden of such systemic problems is staggering. Recent estimates suggest the annual hospital cost of HAIs ranges from $28 billion to $45 billion in the US alone (Kyne, Hamel, Polavaram, & Kelly, 2002). Upwards of 60 percent of HAIs are further due to multi-drug resistant organisms that cannot be treated with most antibiotics and are associated with increased costs, hospital length of stay, and mortality (Spellberg et al., 2008). For example, the excess cost due to HAIs involving methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus is known to be $4,000 per infection, whereas the attributable cost of hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea is $4,500 per patient (Kyne et al., 2002).

In addition, systems exhibit a characteristic known as equifinality, which can be defined as the “many different ways by which a system may reach the same end state” (Infante, Rancer, & Womack, 1997, p. 92). In other words, systems such as healthcare organizations often use many different strategies to achieve a desired goal or outcome. For example, if a hospital is faced with a high nursing turnover rate, it can hire new nurses to replace those who have left the organization or find ways to retain existing nurses in an attempt to improve the situation. Increased medical costs within a healthcare organization can be addressed by laying off staff, finding more efficient ways to provide care, and/or focusing on preventive measures to reduce the number of patients who require costly services to treat certain illnesses.

Communication among members of a system is important to achieving homeostasis and the process of equifinality. In order to achieve a sense of balance or improve the situation when faced with challenging conditions, healthcare organizations rely on input from their members. Individuals and units of an organization are needed to provide solutions to issues that threaten the normal functioning of the organization when they arise. While we have seen that there are often many ways an organization can solve problems or meet goals, healthcare organizations need to find the best strategy for reducing costs and providing quality healthcare. This can be an extremely difficult task for healthcare organizations in today’s dynamic and competitive healthcare environment. We will examine how members of healthcare organizations communicate with one another to adapt to changing conditions later in this chapter.

Types of Healthcare Organizations

There are currently more types of healthcare organizations than at any other time in history, ranging from small clinics and practices to large government agencies. The growth of these organizations in the modern-day healthcare system is due to many factors, including increased specialization, competition in the healthcare marketplace, managed care, changing professional and legal standards, and the diverse health needs of the US population.

Lammers, Barbour, and Duggan (2003) identify some of the many types of healthcare organizations that we see today (see Table 6.1). Some of these organizations are primarily concerned with financing and regulating health services and products, while others are important in terms of accrediting hospitals and other healthcare delivery organizations or influencing healthcare standards and practices, and many are important in terms of healthcare delivery. In addition to these organizations, other organizations are focused on health-related research. It is important to remember that many of these organizations are interdependent or are influenced by one another in other significant ways.

Table 6.1 Types of healthcare organizations

Source: Adapted from Lammers, Barbour, and Duggan (2003).

| Organizations concerned with financing and regulating health services and products |

| Centers for Medicare and Medicaid |

| Insurance and managed care |

| Organizations concerned with healthcare delivery |

| Departments of public health |

| Hospice centers |

| Hospitals |

| Medical groups |

| Nursing homes |

| Parish nurse programs |

| Physicians’ offices |

| Pharmaceutical and biotechnological organizations |

| Professional organizations that influence other healthcare organizations |

| Accreditation organizations |

| Trade and professional associations |

Health insurance organizations are important for helping consumers to access healthcare services, managing the costs of healthcare, and paying providers for their services. The federal government also provides health insurance through Medicaid and Medicare to serve older adults and individuals with lower incomes. We will examine health insurance, Medicare, and Medicaid in more depth later in this chapter.

Healthcare delivery service organizations exist in both the public and private sector, and they can range from small physicians’ offices to large hospitals. While some physicians still work out of private offices, many cannot afford the tremendous costs of running an office, paying staff, and using outside services (such as diagnostic laboratories). These costs have led many doctors to join medical groups where they can share the costs with a small number of other physicians by pooling together resources. Investor-owned and nonprofit hospitals and hospital systems are important healthcare delivery organizations that bring together even more resources than medical groups. Other healthcare organizations include nursing homes, teaching hospitals, hospice services for chronically ill patients, and parish nurse programs in which nurses are hired by churches and other religious organizations to service the needs of their members.

The federal government provides healthcare services for veterans through the Veterans’ Administration Healthcare System and it supports other types of hospitals through federal income tax revenue. Federal government organizations overseen by the Department of Health and Human Services, such as the Center for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Cancer Institute, engage in various types of research that influence healthcare practices within healthcare delivery organizations. State and many local governments have departments of public health or other agencies that provide vital services, such as immunizations, HIV and other sexually transmitted disease screening, prenatal care, and psychological counseling. Pharmaceutical and biotechnology organizations as well as hospital supply companies support all of these healthcare delivery organizations.

Finally, organizations such as JCAHO make sure that hospitals and other healthcare facilities meet certain standards of quality healthcare on a two- to three-year basis. JCAHO assesses and accredits almost 15 000 healthcare organizations in the US in a variety of care delivery functions (JCAHO, 2006). According to Lammers, Barbour, and Duggan (2003), “JCAHO accreditation is important to health organizations because it is required by many third-party payers, state licensing agencies, managed care organizations, and financial institutions” (p. 324). In addition to accreditation, professional associations such as the American Medical Association, the American Hospital Association, and the American Nurses Association influence healthcare organizations by advocating certain standards of practice and lobbying for their interests in Congress.

Communication within Healthcare Organizations

Organizational Information Theory and Healthcare Organizations

Healthcare organizations must confront many challenges on a daily basis at both the macro and micro levels, such as finding ways to cut costs by efficiently managing resources, taking decisions about how to improve healthcare for consumers, making efforts to retain staff, and promoting the organization in an effort to attract consumers and improve business conditions. Communication is central to successfully meeting these and a host of other challenges typically faced by healthcare organizations. Healthcare organizations must use communication to acquire, manage, disseminate, evaluate, and act upon various types of information to function effectively, and communication is a vital component of the interrelationships within an organization (e.g. administrator–provider relationships, provider–provider relationships, and provider–patient relationships) and the interrelationships among healthcare organizations and other organizations within the healthcare system, such as relationships among hospitals, diagnostic laboratories, pharmaceutical companies, and health insurance organizations.

Organizational information theory is a useful framework to assess the various ways in which healthcare organizations use information to function on a daily basis and to meet organizational goals. Karl Weick (1979) developed organizational information theory to describe the process by which organizations collect, manage, and use information they receive. Two important tenets of this theory are that change is a constant within organizations, and that confronting change successfully is necessary for the survival of organizations. For example, in the last 50 years, we have seen hospitals and other healthcare organizations respond to many changes in the health landscape, including provider specialization, the rise of managed care, healthcare legislation (such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act), an increase in the number of female physicians, nursing shortages, an aging population, diseases like HIV and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), and the threat of biological terrorism. Healthcare organizations cannot ignore significant changes and trends such as these in health and healthcare and expect to remain competitive in today’s healthcare market. Organizations must adjust to these types of changes as they occur, and communication plays an important role in the process of adapting to them.

Organizations rely on members within the organization who are skilled in certain areas to interpret information, or the organization can find people outside of the organization (i.e. using affiliations with other organizations or resources) to help interpret the information. Based upon the interpretation of the information, organizations first decide whether the information is relevant or useful to the goals of the organization, then they must decide how to use the information or adapt to it so that organizational goals are met. For example, suppose hospital administrators learn that poor physician handwriting has led to a high percentage of mistakes in filling prescriptions at the hospital pharmacy. While it may be relatively easy to interpret that this information is relevant to the organization and poses a problem to organizational goals (such as providing quality patient care and avoiding lawsuits), finding ways to solve the problem can be somewhat ambiguous. By consulting with a team of experts within the organization, a computer specialist might suggest that physicians use a personal data assistant (PDA) device, where they could select from a list of medications when prescribing for patients, and then the information could be sent by wireless technology from the PDA directly to a computer in the pharmacy. The administrators might conclude that this is the best way to manage the issue, or after consulting with other experts within the organization (such as an accountant) they may feel that this option would be too expensive, and they may continue to seek other information about ways to solve the problem.

According to Weick (1979), organizations engage in communication patterns known as cycles, which include an action, a response, and an adjustment. An action might be a question someone within the organization raises when confronted with an ambiguous problem he or she encounters, such as if a nurse asks why so many children are coming into the clinic with otitus media (an ear infection). A response to this action might be: “I saw this problem last winter during flu season” from a fellow nurse. The first nurse might adjust to this information by alerting physicians that they might expect to see a number of cases in the near future. Of course, when the physicians hear about this problem, it may lead to additional cycles (e.g. more questions, responses, and adjustments). These multiple cycles are known as double interact loops according to Weick (1979).

Most healthcare organizations have formal rules and policies for interpreting and acting upon ambiguous information as it surfaces. In organizations with formal organizational structures, ambiguous information is typically delegated to individuals who specialize in certain areas of knowledge, and many healthcare organizations rely upon hierarchical structures to process information. Hierarchies often have the advantage of processing information quickly and efficiently, but they can be problematic if organizations rely too much on individuals at the top of the hierarchy, such as managers, directors, and administrators, to interpret, process, and disseminate equivocal information. Ambiguous information is often encountered at various levels of organizations. For example, sometimes issues that can affect an entire hospital are first encountered by administrators, while at other times they are first recognized by people on the “front lines” of healthcare, such as nurses and receptionists. Other times pertinent information about an issue that will have a major impact on the organization can come from a particular department within the organization, such as the hospital security department.

O’Hair, O’Rourke, and O’Hair (2001) identify three common forms of message flow within healthcare organizations. When upper managers or administrators identify issues and messages are then communicated to the lower levels of the hierarchy, this is known as downward communication. Conversely, when people at the lower levels of the hierarchy, such as maintenance personnel, encounter information that may be useful to the organization and communicate messages to people at higher levels, this is known as upward communication. When messages are communicated among individuals who share a similar status within the organization, such as information exchanged among nurses, this is known as horizontal communication. Healthcare organizations with traditional hierarchical structures tend to privilege downward communication, and this can be detrimental to the organization since people at lower levels of healthcare organizations often possess important information about day-to-day operations and events that the higher levels of the organization may not be aware of, even though this information can be vital to the organization’s success. For example, charge nurses are some of the most vital members of hospital organizations since they assist other nurses, order medicine, and organize schedules and other duties that appear out of the blue. All too often these important organizational resources are not consulted on the very issues they deal with on a daily basis. Instead, they receive emails and memos dictating policy for the very floors of the hospital they serve.

Messages can also be communicated through formal and informal organizational communication networks (Kreps & Thornton, 1992). Formal communication networks are tied to the structure of the organization, and messages may include emails, memos, handbooks, and other forms of written or oral communication, while informal channels tend to be more interpersonal and are linked to workers’ need for additional information about organizational events and issues. Informal communication networks often consist of relationships that develop within the organization through day-to-day interactions. For example, supervisors make friends with subordinates, employees from different areas of the organization eat lunch and go to happy hour together, and people begin to rely on one another for various types of organizational information, including everyday gossip about personalities and opinions about policy changes and regulations. While a hospital memo might announce that the administration is considering hiring a new director of nursing from within the organization, employees may use friends in different departments or among the administration to find out which individuals might be the best candidates.

Informal leaders can emerge from these networks, and these individuals can sometimes become more powerful than formal leaders, especially when people trust them more than formal leaders. As we will see in the next section, informal networks are an important part of organizational culture, and administrators need to be aware of the influence of informal networks on employee perceptions of the organization and behaviors.

Healthcare Organization Culture

Healthcare organizations use communication for more than processing information and managing uncertainty: communication is central to the development and maintenance of relationships and the creation of organizational culture. A culture can be defined as the beliefs, assumptions, attitudes, and values a group of individuals share about the world based upon common experiences. In other words, when people share similar experiences on a regular basis, they often develop similar ways of seeing the world. All of us are members of many different cultures that are based upon common interests or shared realities due to common experiences (e.g. communication majors, sororities and fraternities, religious organizations, clubs), and like the cultures of these groups, members of healthcare organizations develop unique ways of seeing the organization and their experiences within it through day-to-day interactions.

Communication scholars who take a cultural approach to organizations argue that individuals within organizations create meanings for everyday events that occur in organizations, and they ultimately develop a unique sense of organizational reality (Eisenberg & Riley, 2001; O’Reilly, Chatman, & Caldwell, 1991; Pacanowsky & O’Donnell-Trujillo, 1982). These scholars contend that organizational members constantly create meanings for the behaviors they observe within the organization in an attempt to make sense of their world. The meanings that individual members create are shared with others through different forms of communication within the organization, such as symbols, stories, and rituals. These messages as well as the physical layout of hospitals, clinics, and other healthcare organizations can reflect the beliefs, attitudes, and values of an organization.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree