Chapter 29 COMMUNICATION

Communication involves the ability to interact with people at a variety of levels and in a range of situations. Effective communication is important in all areas of everyday life; the quality of relationships between people depends on it. Nurses need to communicate effectively with everyone in the health care environment, and therapeutically with clients. The ability of nurses to communicate therapeutically is a critical factor in how clients experience illness. Nurses need to be skilful in what they do for clients but at the same time they need to be communicating with them in ways that are supportive and helpful and promote feelings of trust. While the focus of this chapter is on therapeutic nurse–client interactions, the skills involved will enhance communication in all relationships between people.

The nurse who has effective communication skills:

All communication is a two-way process in which messages are conveyed by verbal and/or non-verbal means by one person, and received by another. All behaviour conveys some message and is therefore a form of communication. For example, even a client refusing to speak or acknowledge the presence of a nurse conveys a message that the nurse will attempt to interpret (decode). Non-verbal communication includes the messages sent by facial expression, gestures, body posture and appearance, and those that are written (see Chapter 20 for information concerning written communication in nursing).

ELEMENTS OF THE COMMUNICATION PROCESS

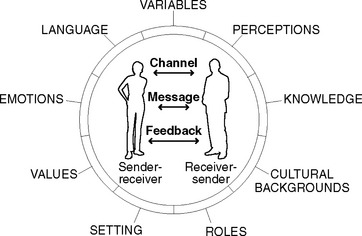

Communication is a multidimensional and complex process in which ideas, thoughts, values, knowledge or feelings are shared and interpreted. During the process people simultaneously send and receive numerous messages at many different levels. To simplify understanding of this complex process, models of communication have been developed. Figure 29.1 is an example of one such model. It depicts the basic elements of communication and shows that communication is an active process between sender and receiver. The process of communication involves:

When communication is occurring and information is being transmitted from one person to another, two processes must take place: encoding and decoding. Encoding refers to the cognitive processes that occur in the mind of the person who is to send the message. These thoughts must be translated into a code, such as verbal language, to be transmitted to the person who is to receive the message. Decoding refers to the cognitive processes used by the receiver of the message to make sense of what is seen or heard. Generally the sender and the receiver encode and decode messages in a cyclic pattern while communication is taking place. Clinical Interest Box 29.1 illustrates the communication process in action.

FACTORS THAT INFLUENCE THE COMMUNICATION PROCESS

Even during a simple act of interpersonal communication between two people, many factors can influence how effectively messages are conveyed and understood. These factors are frequently referred to as the variables (Figure 29.1); they relate to anything that influences or interferes with how the sender transmits a message, how the recipient perceives (interprets) the meaning of the message and the route or channel of communication.

PERCEPTION

Perception is a process by which the meanings of messages are interpreted. The way messages are perceived is related to a combination of a person’s social and cultural influences, gender, educational background and knowledge, and past experiences. This complex mix of influences means that no two people are likely to perceive the same message in exactly the same way. Some of the strongest influences on the way messages are sent and their meanings perceived are the attitudes, values and beliefs that individuals hold (Stein-Parbury 2005; Williams 2007).

ATTITUDES, VALUES AND BELIEFS

Attitude towards others is also related to the values and beliefs that a person holds about the ideas or practices of other people in society, and they are not always consciously recognised. For example, cultural values commonly lie outside conscious awareness and are often simply taken for granted as being the right values (Stein-Parbury 2005). It is natural for people’s values and beliefs to differ within and across social and cultural groups. Nurses will encounter many situations in which their own cultural values and beliefs differ from those of clients (see Chapter 9). Tolerance and understanding of differences in views and cultural practices helps to facilitate therapeutic relationships between nurses and their clients. For example, a nurse who holds strong values and beliefs about no sex without marriage will need to demonstrate acceptance that personal views are not shared when caring for a pregnant, single, female client. If the nurse is unable to accept this and put personal views to one side, it will be difficult to communicate with the client in a therapeutic manner.

While a nurse’s personal values can create interference in therapeutic relationships if they are imposed on clients or used in judgment, they can also serve to enhance therapeutic effects. For example, a nurse who holds beliefs that all people have positive qualities and that every individual is a worthwhile person will find that such beliefs enhance the establishment of effective therapeutic relationships (Antai-Otong 2007; Stein-Parbury 2005).

EMOTIONS

Emotions strongly influence how a person relates to other people, and the power of emotion in communication should not be underestimated. Nurses must also be aware that if they become too emotionally involved with the suffering experienced by a client, they may be unable to effectively meet that client’s needs. This aspect is one of the most difficult situations faced by nurses, as on the one hand nurses must become emotionally involved to assist clients, while on the other hand personal emotions cannot be allowed to adversely affect client care. All nurses need to be aware of their emotions, and many find it helpful to talk with other experienced nurses about what they are feeling and experiencing.

RELATIONSHIPS AND ROLES

The nurse–client relationship is unique: trust in the nurse needs to develop quickly and trust is essential if the relationship is to be therapeutic. Clients in hospital may not say what they are thinking or feeling if there is a lack of trust in the nurse; often this means that the client has a fear of being judged. A therapeutic relationship means demonstrating unconditional acceptance of all clients, without judging (Stein-Parbury 2005; Williams 2007). The nurse accepts the client as a worthwhile person even if the client’s behaviour is challenging. As a nurse’s communication skills develop they become increasingly effective and therapeutic, but even when they have been learned and practised they may still be difficult to apply in some particularly challenging situations. Clinical Interest Box 29.2 provides examples of situations where communicating effectively with clients can be challenging.

ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING

Effective communication is more likely to occur if it takes place within a setting that is conducive to listening and concentrating. An area that is at a comfortable temperature, private and free from noise and other distractions is suitable, whereas an area where there is noise or a lack of comfort or privacy may create tension and confusion, making effective communication difficult. For example, background noise and the movements of other people in the environment may distract the listener, and even missing one or two vital words in a sentence can result in the meaning of a whole sentence being lost.

FORMS OF COMMUNICATION

VOCAL COMMUNICATION

Tone and pitch

The tone and pitch of the voice can have a powerful effect, sometimes more so than words. No matter what words are being said, a loud aggressive voice will send a strong message. A nurse’s tone and pitch of voice and the inflections used add meaning to words. Tone and pitch of voice can display anger, apathy, disgust, enthusiasm, excitement and other emotions. An individual can often determine more about another person from the way in which the words are spoken than from the actual words used. Loud, rapid, forcefully spoken words can intimidate and communicate aggression, a patronising tone can communicate condescension or contempt, and expressionless speech can communicate lack of interest. A client and nurse can discern much about each other from their respective voices. Of particular importance, the tone and pitch of clients’ voices can convey messages about their emotional feelings and energy levels.

The use of pauses

NON-VERBAL COMMUNICATION

It is generally accepted that non-verbal messages form the most significant component of communication. Research conducted by Professor Albert Mehrabian (1972) first identified that in conversations messages transmitted and received are about 7% words, 38% tone and pitch of voice and 55% non-verbal clues. These percentages have not been contradicted by any other research, neither has the proposition, identified by Mehrabian (1972), that most non-verbal messages are about emotions and that they are mostly automatic, and so more reliable than words because they are not as easy to fake (Mehrabian 1972). Perhaps that is why there is a saying that ‘actions speak louder than words’.

Facial expressions

Facial expressions convey emotional states, and so a great deal of information can be obtained about clients’ feelings by observing their facial expressions. For example, a frown or an eyebrow raised in disbelief reveals something of how a client is reacting to what is being said. Some specific facial expressions of emotion seem to be universal across cultures. They are those that convey surprise, fear, disgust, anger, happiness and sadness (Ekman 1997). Facial expressions provide the nurse with continual non-verbal feedback from most clients, but some people have expressionless mask-like faces that reveal little or nothing of what they are thinking or feeling. This may be a client’s usual demeanour but sometimes it is due to the effects of an illness such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s dementia or severe depression. In such cases the nurse must detect the client’s mood from other clues such as body posture, activity level, appetite or simply by asking how the client is feeling.

Facial expressions can attempt to mask true emotions, for example, a client may smile to hide feelings of sadness, anxiety or boredom. This may be so as to not worry loved ones, not to concern the nurse, or to keep feelings private. Facial expression may be incongruent with what a person is saying; for example, a client may be smiling while talking about a very sad event, such as the death of their child. In such cases the client would be described as having ‘an inappropriate affect’ (Varcarolis 2006).

Body movements and gestures (body language)

Conversely, a specific gesture may be meaningless or assume a different meaning in another culture. For example, the ‘V’ sign made with two fingers may mean victory, the number two, or something rather rude. Even within one culture the meaning may be different according to whether the gesture is made with the palm facing out or facing in. In most European countries the V sign means victory when gestured with the palm facing away from the body and a rude ‘shove it’ when the palm is facing towards the body of the person gesticulating (Haynes 2002). It is not uncommon for an acceptable gesture in one culture to be considered rude in another. For example, pointing at an object with the index finger is considered impolite in the Middle and Far East. In Indonesia it is common and more acceptable to use an open hand or thumb (Haynes 2002). (See Chapter 9 for more information on cultural difference.)

When a person’s actions or gestures do not match spoken words, the messages are said to be incongruent. This means that the body movements or gestures are conveying one message, while the verbal words are conveying a different message. When a client conveys incongruent messages it is important that the nurse tries to clarify what is happening even though it may at first feel awkward doing so. Clinical Interest Box 29.3 provides an example of how a nurse can explore incongruence between verbal and non-verbal messages.

Eye behaviour

In some cultures the norms about what eye contact means, how often it should occur and with whom, are quite different to those of the white Anglo Saxon population. According to their cultural norms, people try to balance their eye contact somewhere between staring and avoiding all contact. Some of the differences in eye behaviour include that Japanese people tend to gaze at the neck rather than at the face when conversing; Southern Europeans tend to have a high frequency of gaze that may be offensive to others; people from Arab countries tend to use prolonged eye contact to gauge trustworthiness; in Asia, Africa and Latin America people avoid eye contact as a sign of respect (Stern 2004), and eye contact can make Aboriginal people feel awkward, so they may look the other way during conversations (Kimberley Interpreting Service 2003). Nurses therefore need to consider cultural differences when using eye contact with clients.

Looking down on a client from a higher position can be intimidating. When clients are in bed it is preferable for the nurse, or any other health professional, to sit down and make eye contact at eye level because communicating at eye level indicates equality in a relationship. Conversely, rising to the same eye level as a person who is angry, bossy or intimidating in any way may reduce feelings of vulnerability because it helps to establish a more equal sense of power (Crisp & Taylor 2005).

Touch

Touch (tactile communication) is one of the most powerful and personal forms of expression. A person’s first comfort in life comes from touch, and so, frequently, does their last, as touch may communicate with a dying person when words cannot. There is no way to practise nursing without touching and, in nursing, touch may be the most important of all non-verbal communications. Touch occurs in everyday procedures such as taking vital signs and assisting clients with showers or baths. It also occurs at times of joy, fear, stress and loss (see Chapter 14 concerning loss and grief). How nurses use touch in client care conveys a great deal about the way they feel towards their clients and their illnesses.

Some people, including nurses, appreciate the significance of touch as a therapeutic act so much that they perform the techniques of relaxation massage or the ‘laying on of hands’. Massage, performed skilfully and sensitively, can produce relaxation and can communicate caring. Laying on of hands involves placing the hands on or near the body of an ill person in an attempt to heal (Rankin-Box 2001). In nursing, touch can be used therapeutically to transmit positive feelings of understanding, compassion or reassurance. To be effective, tactile communication must be used at the appropriate time and place. Not all people like to be touched and all individuals consider a certain amount of space around them as private. Touch can be seen as an invasion of that privacy unless it is desired. Touch must be used at the right time and in the right way, otherwise the message may be misinterpreted. Nurses always need to assess and be sensitive to how comfortable the client is with being touched.

Space

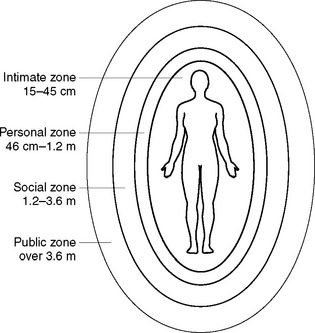

The concept of ‘space’ is important in communication, as it determines the distance a person usually keeps between themself and other people. The individuals involved and the context or situation dictate acceptable distance zones. People surround themselves with their own ‘informal’ personal space, which is invisible and mobile. There are four categories of space or zone (Figure 29.2).

Individuals have their own personal tolerance for touch, closeness and distance, which is often also influenced by cultural conditioning. For example, some Asian people may feel very uncomfortable if they are touched on the head because the head is the repository of the soul in the Buddhist religion (Haynes 2002). When two people are communicating, each person makes personal space decisions and attempts to maintain an ‘acceptable’ boundary of personal space. Sometimes the personal space expectations of each person conflict and the result is spatial invasion. Spatial invasion makes people very uncomfortable and precipitates a communication reaction of either fight or flight, neither of which is helpful in promoting communication. Most people have experienced a situation when, during a conversation with another person, that person moves in uncomfortably close to make a point. The first person often feels this as an invasion of personal space and responds first by pulling the head away. If this first non-verbal cue is not received, the person may even step back and move away.