INTRODUCTION

The ways in which people communicate have profound effects on those around them. It is over 50 years since Peplau (1952) took the first steps in redefining nursing as an interpersonal, interpretive process (Tilley 1999), providing one of the first manifestos for the study of nursing as a communicative process:

nurses – like other human beings – act on the basis of the meaning of events to them, that is, on the basis of their immediate interpretation of the climate and performances that transpire in a particular relationship. At the same time, the patient will act on the basis of the meaning of his illness to him. The interaction between nurse and patient is fruitful when a method of communication that identifies and uses common meanings is at work in the situation.

(Peplau 1952: 283–284)

The impact of this view of the nursing encounter has been profound and there has been an explosion of research and theory on communication processes in health care. Indeed, a recent search of the CINAHL® (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health) database yielded nearly 5000 citations in response to the terms ‘nursing’ and ‘communication’. Consequently, it is important for practitioners to understand the major trends and topics in the study of communication, and to incorporate this knowledge within professional practice. It is clear that communication is a life-changing activity and very different results can emerge from the process of caring for others depending on how it is performed. Inadequate inter- and intraprofessional communication, as well as poor communication between staff and patients, has been consistently cited as a cause for concern by Ombudsman reports on the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK (Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman 2006). ‘Communication is a cornerstone of the nurse–patient relationship. The power of effective nursing care is strengthened and enriched by good communication’ (Sheldon et al 2006: 141).

This chapter addresses a variety of facets of the communication process in health care. The study of communication is a lifetime’s work; the examples presented here demonstrate its importance in the life of an effective and compassionate practitioner.

OVERVIEW

Subject knowledge

In this section the theory and modes of communication are introduced. The biological basis of communication is outlined through describing the sensory organs and the interpretation of language and non-verbal signals in the brain. Insight into ideas about how and why human beings come to be language users is an important area to understand. Knowledge of the rich and versatile range of gestures, sounds and facial expressions which go to make up face-to-face communications is important for nurses. Finally, modes of communication that are used by health professionals to both care for, and control, clients are discussed.

Care delivery knowledge

There are various aspects to communication in care delivery, from questioning, interviewing and assessing patients to information giving, teaching and promoting health. At the heart of all communication should be general counselling skills and the means of developing a therapeutic relationship. In addition, care professionals need to keep accurate and appropriate records and need to be able to deal with a variety of communication difficulties. In performing these activities, however, it is important to consider how language can be used to comfort, socialize and establish roles as well as to restrict and punish individuals.

Professional and ethical knowledge

In this section, legal and ethical issues concerning record keeping are considered. The implications of good and bad record keeping are contrasted and the implications for service users, care workers and professionals are discussed. The quality of care that clients receive can depend on adequate communication so in the final section of this chapter, the nurse’s role in client advocacy within this context is examined.

Personal and reflective knowledge

This chapter will enhance awareness of the importance of language in nursing and provide a basic understanding of what it takes to be a critical and sensitive communicator. This section helps you to reflect on the implications of issues raised within this chapter for your day-to-day practice. On pages 39–41 are four case studies, each one relating to one of the branch programmes. You may find it helpful to read one of them before you start the chapter and use it as a focus for your reflections while reading.

SUBJECT KNOWLEDGE

CONCEPTUALIZING COMMUNICATION: MODELS AND THEORIES

Communication is at the heart of all individuals’ interpersonal lives – that is how they relate to others – and also their internal worlds of thoughts and feelings. Most people move freely in and out of these two realms of dialogue throughout their waking hours. Indeed, humans are always communicating – to themselves or to others. If they are not speaking, writing or gesticulating, then they are likely to be receiving messages from others. Thus, it is impossible to switch off communication since everything individuals do, even silence, sends out messages.

Sit quietly for a few minutes and think about all the different kinds of communication going on around you.

• What do you hear, see, think and feel? As you do this, you will be experiencing the internal monologue of your own thoughts, and external verbal and non-verbal exchanges of other people. You will remind yourself that communication is the most important or central human activity.

• Extend this exercise by spending 5 or 10 minutes observing the kinds of communication that take place in your practice area. You may wish to repeat this activity at different times of the day or in different clinical situations. If applicable, record your findings in your portfolio.

In considering communication, the first task is to consider ways in which scholars have attempted to define and model the communication process. How people send and receive messages and the kinds of messages involved is complex. A number of scholars have tried to build models or metaphors of the communication process.

GENERAL MODELS OF COMMUNICATION

Early beginnings: the one-way flow

One of the oldest ‘folk models’ of communication sees it as a kind of conduit, where thoughts are translated into words and language transfers the thoughts bodily from one person to another. This began with Shannon & Weaver’s (1949) model of communication, where an information source passes the message to a transmitter and the message then passes down a channel (originally, a telephone wire) and reaches the destination or recipient. This kind of thinking is also found in Lasswell’s (1948) classic formula ‘Who says what to whom in what channel with what effects’. These metaphors of communication tend to see communication as being rather like the transport of goods, services and people (Carey 1989). Examples of communication conceived upon this model include information sheets about drugs or illnesses, leaflets, pamphlets books and latterly websites where information is, hopefully, transmitted to the reader.

Communicating as a transaction: the two-way flow

In contrast to the one-way flow model, some researchers and theorists have proposed two-way or transactional models of communication (Ratzan et al 1996). Two-way communications are the preferred model in nurse–patient exchanges because they involve dialogue between sender and receiver where shared meaning and mutual understanding can be more easily developed. In other words, they involve a feedback loop (Kreps 2001). In health care, feedback is sometimes invited through questionnaires or given as part of teaching or supervision, but equally influential are the nods, smiles and ‘uh-huh’ sounds that people use during conversations.

Cognitivist models

These models of language emphasize how we process and interpret the information and explore how communication may be subject to psychological factors, hence the term ‘cognitivist models’. Language is believed to be shaped by the individual speaker’s intentions, mental representations, the neurological basis or ‘hard-wiring’ of their language faculties, and decoded in terms of the receiver’s interpretative frameworks to make sense of any message (Chomsky, 1993 and Fodor, 1998). Thus, in this model, any communication can be influenced by beliefs, values, assumptions and prejudices. Additionally, perceptual differences and distortions among individuals can affect communication. Any social event or situation will yield a variety of interpretations depending upon who perceives it. In this view the language is a window into the mind and what we say or write reflects a variety of preceding cognitive, emotional and neurological states. For example Reilly & Lambrecht (2001) argue that nurse–patient communication will improve if nurses develop an appreciation of patients’ thoughts, feelings, situations and behaviour.

Contexts and intentions of communication

Another way of making sense of communication is to consider the context and purpose for sender and message, following the Russian linguist Roman Jakobson (1960). In this tradition, theorists are also interested in how the context or circumstances in which individuals find themselves determines the meaning of any message. People are believed to engage in a good deal of ‘recipient tailoring’ to make the speech suit the situation (Brown & Fraser 1979).

Language as action: the theory of speech acts

All communication is a kind of action, that is, it has a purpose – promising, warning, threatening, praising, apologizing and so on (Searle 1979). Communication is fundamentally an activity; it is a way of doing things and getting others to do them. In Habermas’s (1995) theory of communicative action, humans establish their persona or identity through communication with others. Sumner (2001) notes that these communicative actions in nursing can, if successful, lead to a sense of fulfilment and validation for client and carer. Hyde et al (2005) agree with Habermas that effective communicative action can make social processes such as nursing more empowering and democratic.

Language as a construction yard: co-constructing realities through language

In contrast to the above humanistic models of communication, there are other ways of conceptualizing the process of communication. To some students of communication in health care, language is a way of constructing reality in healthcare encounters. In this sense language is a kind of construction yard where versions of reality can be created (Potter 1996). As Fox (1993) demonstrated, a patient who has just undergone an operation may be in a great deal more pain than before the intervention, yet it is the job of the medical team to put a favourable gloss on this often unhappy situation. They do this by focusing on upbeat topics like the number of days until discharge, or until the stitches can come out.

This construction yard model of communication may sound abstract, but it is a useful way to think about the process of communication in nursing. For example, Bricher (1999: 453) describes how trust can be constructed between nurses and sick children. As one of her respondents said: ‘I show them a photo of my dog and they realize … that you’ve got a backyard and a dog too, … not just this person that sticks suppositories up’. Within children’s nursing, this focus can be particularly valuable. Trust is important in healthcare relationships (Sellman 2007); it enables treatments to be undertaken with a minimum of distress, and even when a distressing procedure is undertaken, the relationship can be quickly re-established.

Think of a recent communication that you have made. The task in this exercise is to think about it in relation to the various models we have presented.

1 The transmission model – what did you transmit to the other person or people? What did they transmit to you? What were you thinking at the time? What do you suppose they were thinking? To what extent was it a transaction?

2 The contextual model – how did the context influence the communication?

3 Communication as action – what were you trying to achieve in the interaction? What were you trying to get the other people to do? What were they trying to get you to do?

4 Language as a construction yard – did the communicative event construct or formulate reality in a particular way? Why? What alternative formulations of reality might there have been?

5 Write an account and analysis of an episode of communication you had with a patient and/or a colleague.

So far this chapter has presented a variety of theories related to communication, and sketched out a number of different research approaches, demonstrating what language may do in health care. But how did human beings become technically competent as communicators in the first place?

THE BIOLOGICAL BASIS OF COMMUNICATION

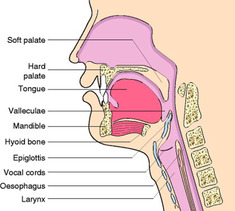

Communication is founded in human anatomy and physiology. In speech, several parts of anatomy are involved: mouth, nose, pharynx, epiglottis, trachea and lungs (Fig. 2.1). These combine and relate to produce particular kinds of sound that make up the medium for conveying messages to others. But beyond direct speaking mechanisms, other parts of the body support and bring about communication. From the ears and eyes to complexes of muscles and the nervous system, individuals are able to do such things as type on a keyboard, write, or produce and receive a vast range of verbal and non-verbal messages. Moreover, this activity is facilitated by a variety of neurological processes. The next section examines these in more detail, beginning with a summary of mechanisms of speech.

|

| Figure 2.1 (after Kristen Wienandt Marzejon, with kind permission; kristen@medartdesign.com). |

Mechanisms of speech

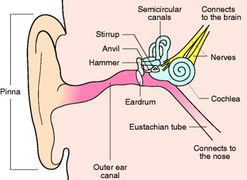

To speak is to articulate sound by pushing air out of the lungs, through the trachea and into the larynx where vocal cords take up one of two positions. When the vocal cords are drawn together like a stiff pair of curtains, the air from the lungs has to push them apart, and this causes a vibration which can be experienced by placing a finger on the top of the larynx and producing sounds like [z]. Sounds made this way are described as ‘voiced’. When the vocal cords are left apart, however, air passes silently to make ‘voiceless’ sounds such as [s] or [f]. In its journey onwards, the air passing through the larynx moves into the mouth and/or nose where sounds are formed by changing the shape of the oral cavity, notably with the tongue. Many of the sounds produced in this way form words, but a significant proportion form what have been termed ‘guggles’ or paralinguistic cues – expressions of surprise, support, ‘um hmm’, ‘ah ha’ and so forth which may be used to support and encourage a speaker or to indicate that a person wishes to interrupt. They are an informative part of the ‘music’ of conversation (Scherer et al 2002). Once sounds have been made, they must be perceived for communication to take place. In the ear, sound waves – a kind of ‘compression wave’ in the air – are converted into nervous impulses and enter the brain via the cochlear nerve. The basic anatomy of the ear is shown in Figure 2.2. Sound waves enter the ear via the pinna and outer ear canal and vibrate the eardrum or tympanum. This transmits vibration via the bones of the ear (the hammer, anvil and stirrup) to the cochlea, which is rich in nerve endings that are able to detect the minute deformations in the tissues caused by the vibrations and turn them into nerve impulses. These impulses then pass along the auditory nerve to the midbrain and then to the auditory cortex of the temporal lobes. The processing of sound into meaningful units of communication is not well understood, but it is possible that different brain cells or groups of cells specialize in the recognition of certain sounds.

|

| Figure 2.2 |

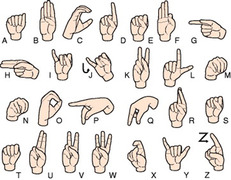

Communication difficulties and disabilities

If the sensory processes themselves are impaired, this can lead to communication difficulties. There are a variety of techniques which can be used to compensate for these impairments. For example, as well as mechanical aids such as implants and hearing aids, deaf and hearing impaired people can use a number of strategies to communicating which rely on the hands. A variety of techniques such as sign language (Fig. 2.3) and finger spelling may be employed (http://www.british-sign.co.uk) to convey meaning. There are also a variety of aids to help visually impaired people communicate, including: glasses, Braille, large print, books and magazines on tape, dark lined writing paper or even a grooved writing board, through to electronic aids such as label readers or voice recognition phone diallers. One critical aspect of non-verbal communication is the interpretation of facial expressions of emotion, and children with learning difficulties have been found to be less accurate than non-disabled children in making such interpretations. As Bandura (1986) has pointed out, the ability to read the signs of emotions in social interaction has important adaptive value in guiding actions toward others.

|

| Figure 2.3 |

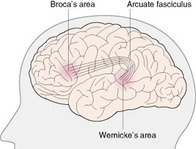

Message interpretation in the brain

The ability to use language is located in the brain, and debate has ensued about the locality for this specific function. The role of Broca’s area in the human brain in the production of speech and Wernicke’s area in understanding the significance of content words in speech has been appreciated since the 19th century (Dronkers 2000; Fig. 2.4). These two areas are linked by a bundle of nerve fibres called the arcuate fasciculus. These two main areas have been studied closely in relation to various forms of brain damage and how such lesions affect language production. Damage to Broca’s area is related to difficulty in producing speech, while damage to Wernicke’s area is related to speech comprehension difficulties. In addition, a part of the motor cortex, close to Broca’s area, controls the muscles that articulate the face, tongue and larynx – all key to language production – which when damaged also affect communication.

|

| Figure 2.4 |

If a client were to hear a word and repeat it, this suggests a simple transmission of a word being heard and understood in Wernicke’s area; this area transfers a signal via the arcuate fasciculus to Broca’s area, where production of the word is set up with a signal being sent to the motor cortex to put it out in a physical form by moving particular muscles, etc. Yet there is evidence that a large number of different areas of the brain are used for the production of spoken utterances (Posner & Raichle 1997) and that different areas of the brain are activated for different aspects of speech. Hence, a rich variety of anatomical and physiological mechanisms and senses lie behind human communication, and scientists are still examining this complex phenomenon, just as they still have much to understand about consciousness itself. Thus, in contrast to a localized view of language functioning in particular parts of the brain, it appears that this human skill is wrapped up with interdependent aspects of brain function.

Sometimes people’s predispositions may make them less likely to interpret cues in a particular way. For example those who are apt to be cynical or hostile are likely to misattribute happiness (Larkin et al 2002). Research has also revealed gender differences in the accuracy of decoding facial expressions of emotion, with males being less accurate than females (Pell 2002).

Language acquisition

It is extraordinary how children acquire language. As well as becoming competent users of a complex syntax, on average English-speaking children acquire a vocabulary of about 60 000 words by the age of 18. The early stages of children’s communicative learning are outlined in Table 2.1. During peak vocabulary development periods during childhood this means learning a new word approximately every 2 hours. This has led some theorists, such as Chomsky, 1976 and Pinker, 1994, to suggest that there are somehow inbuilt – or as cognitive scientists sometimes say, ‘hard-wired’ – cognitive and neural structures that enable the grammar and lexicon to be learned so readily: in Chomsky’s phrase, a ‘language acquisition device’. This is debatable, however, and critics charge Chomsky and Pinker with paying insufficient attention to the sheer diversity of the world’s languages, or with not considering how difficult it is to explain language in evolutionary terms (Allott 2001). At the present state of knowledge, communication is far more than biology alone can explain, and to make sense of how communication has come to be employed we need to make sense of the evolution of cultural themes too (Oudeyer & Kaplan 2007).

| Child’s age | Communication development |

|---|---|

| 0–4 months | Babies start to coo and produce vowel sounds. Will make sounds back when spoken to |

| 6 months | Laughing. Will start to make consonant sounds like d, p and m |

| 6–12 months | Laughing, smiling babbling. Multisyllable speech such as uh-oh, da-da. Points to objects of interest |

| 12–24 months | Development of vocabulary – about 50 words by 18 months, or 100 by 24 months |

| 2–3 years | Builds sentences such as ‘doggy go home’. Acquires concepts such as ‘in’, ‘under’ or ‘behind’ |

| 3–5 years | Development of vocabulary and syntactic ability (the grammatical arrangement of words). Can phrase requests. Sentences get longer. Working vocabulary of about 2300 words by the age of 5 and ability to comprehend 8000 words |

Non-verbal communication

Much human communication is delivered through non-verbal channels or ‘body language’, and is not dependent on sound. Through gestures, postures and facial expressions, people convey rich vocabularies to others. Early attempts to study these phenomena identified about 20 000 different facial expressions (Birdwhistell 1970), which, when combined with gestures and movements yield about 700 000 different possibilities, which may or may not be meaningful (Pei 1997). Non-verbal communication involves a variety of issues (Patterson 1983). Some functions concern how an individual feels towards another person. That is, non-verbal communication may express feelings such as like or dislike; it can establish dominance or control; or it can be used to express intimacy, perhaps by touching and mutual eye contact. Non-verbal signals can be used to regulate interactions, for example by signalling the approaching end of an utterance or the desire to speak, or they may facilitate goal attainment, for example by pointing. Facial expressions add to this visual richness, especially through changes to the eyes and mouth. In interaction in contemporary Western cultures participants typically spend about 60% of the time gazing at one another and these gazes typically last about 3 seconds (Argyle & Ingham 1972). Mutual gazes take up 30% of the time, with the actual gaze lasting about 1 second (Kleineke 1986). The eyes often signal that a person is ready to speak or to end communication. The use of body space – how close people position themselves to others (proximity) – and the shape or posture they adopt affect how messages are sent and received. Whether individuals touch others, and how they do this, and what clothes they choose to wear signal messages such as status and bring yet more dynamics to communication. The issue of how well-attuned a healthcare professional is to the client’s communicative preferences is therefore important. If healthcare professionals make decisions or communicate in a way that fails to account for clients’ cultural beliefs and preferences, then the client’s self-care, adherence to advice and overall outcome may well be poorer (Stewart et al 1999).

Think of different styles of communication associated with different kinds of emotional tone. How would you speak and act if you were:

• Bullying?

• Nervous?

• Confident?

• Humorous?

Evidence suggests that people who are being abused would often like to talk to a health professional about it, but are unsure of how to broach the subject (McAfee 2001). Imagine that you had a client whose physical symptoms suggested that she came from an abusive family situation.

• How could you make it easier for her to disclose the problem? (Bear in mind that people in such a situation might not necessarily disclose this in response to a direct question.)

• Think about how you could use style of speech, vocabulary, delivery, facial expressions and gestures, or even the seating arrangements in the room to make it easier for the client.

• What systems should be in place to support you in dealing with this client?

Graphical communication

Drawing and graphical communication can be an important tool in the hands of nurses and their clients. Indeed, it may be especially useful when communicating with people from different language groups or with people who suffer sensory or communicative impairments. For example, there are cases of people who have been severely communication-impaired following a stroke but who have become functional communicators once more through drawing (Rao 1995). Some authors have also noted the way that drawings provide a useful window into the emotional lives of children who have suffered a traumatic event such as bereavement (Clements et al., 2001 and Wellings, 2001).

PSYCHOSOCIAL FACTORS INFLUENCING COMMUNICATION

Communication takes place in a whole range of environments, involving people with a variety of identities and outlooks. Communication is affected by variables such as age, gender, social class, culture and ethnicity that can influence its content and style. Although this makes sense intuitively, it has been difficult reliably to identify specific markers or interpersonal differences in speech style (Hogg & Vaughan 2002), perhaps because people are extremely flexible and usually competent in several different speech styles. A person may be able to speak some version of the ‘received pronunciation’ (RP) or formal, official language in which a good deal of institutional business is done, yet at the same time, socially, may use a dialect or less formal language such as slang. The kind of language used, rules or laws of social behaviour, the social status and power relations of participants and the roles or life scripts that they have adopted may equally affect communication.

Observe some interaction between consultant and nurse or nurse and patient. Look at the way they communicate. Observe who is in charge and note how this is manifested.

• How could you use this observation in your practice?

• For example, a patient adopting a ‘sick role’ may communicate in a very passive, dependent way. How would you counteract this tendency?

• If a consultant dominates a multidisciplinary team meeting, what might you as a nurse do to change the balance of power?

The speech style of a person in a powerless position tends to involve the use of features such as:

• ‘intensifiers’, e.g. ‘very’, ‘really’ and ‘so’

• ‘hedges’, e.g. ‘kind of’, ‘sort of’, ‘you know’

• rising intonation, which makes a declaration sound like a question

• polite forms of address (Lakoff 1975).

Power can be associated with the ability to interrupt and take control of the ‘floor’ in conversation (Reid & Ng 1999). Nearly 30 years ago, Zimmerman & West (1975) noted that 98% of interruptions were by men. More recently, although the situation has become more equitable, men are still more likely to interrupt, especially when interaction is studied in field settings and when there are more than three people present (Anderson & Leaper 1998).

Interruptions can be considerably more than a nuisance. Individuals who interrupt a good deal may be doing this as part of the ‘Type A’ behaviour pattern, characterized by loud speech and frequent interruptions, as well as a rapid speech rate, hard-driving hurried behaviour, impatience and hostility. The Type A behaviour pattern has been associated with an increased likelihood of heart disease, originally by Friedman & Rosenman (1959), with the interest in speech styles being pursued by other researchers more recently (de Pino-Perez et al., 1999 and Zwaal et al., 2003). Indeed, Ekman & Rosenberg (1997) note that as well as rapid and aggressive speech, Type A behaviour is associated with more facial expressions of glare and disgust. Thus, communicative style can be a valuable clue that a person’s lifestyle may be making them more vulnerable to illness (Zwaal et al 2003) and increasing their social isolation (Chen et al 2005). Friedman & Rosenman were cardiologists and their initial ideas were stimulated by noting that the edges of the seats in their consulting rooms wore away. Eventually they deduced that this was to do with the ‘edge of the seat’ stance of their impatient patients.

Gender differences in speech styles are not innate in any obvious sense, but reflect status differences in situations. We may anticipate changes in the pattern of gender differences as greater social, economic and occupational equality is achieved. In the meantime, Fairclough (1989) argues that nurses, among others, should be aware of ‘how language contributes to the domination of some people by others’ and suggests that being conscious of this ‘is the first step towards emancipation’ (Fairclough 1989: 1).

Awareness of language and communication thus involves an awareness of the diverse range of biological, personal and social factors that have an impact on the speech styles in use in health care. Becoming aware of these factors can enable nurses to work to change the situation to the benefit of clients and nurses themselves.

USING LANGUAGE IN HEALTH CARE

An individual’s capacity for communication does not remain static, but changes over the lifespan, and adult communicators will be concerned with how to be efficient and effective communicators and avoid the pitfalls of communicating in limited, negative or harmful ways. The notion that language might be harmful is of particular importance in the context of health care, where the overriding premise is to promote human well-being (Crawford et al 1998).

Language, ideology and power

Nursing communication takes place in a context informed by wider political and economic directives, and involves communication with other healthcare professionals and patients. As such, it is caught in a web of powerful conceptions and ideologies of what society should be like, how it is constructed and what is important. According to Fairclough (1989), nursing is shaped by powerful ideologies of bureaucratic ‘cost-effectiveness’ and ‘efficiency’, and nurses’ training tends to promote acquisition of communication or social skills ‘whose primary motivation is efficient people-handling’ (Fairclough 1989: 235). This may tempt nurses to communicate in a way which has more to do with economics, politics and the public image of the institution for which they work than with their profession’s or their own value systems. The increasing conviction on the part of policymakers in the UK that there has been a power imbalance between patients and health care providers has led to a number of initiatives to try to ensure that patients’ voices are heard. Of particular interest in the UK is the Commission for Patient and Public Involvement in Health (http://www.cppih.org), established in January 2003 as an independent public body, sponsored by the Department of Health, to ensure public involvement in decision making about health services. Across England there are over 400 Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) forums comprising volunteers in local communities who are involved in helping patients and members of the public to influence local healthcare delivery (Commission for Patient and Public Involvement in Health 2006). In an effort to strengthen the ‘local voice’ further, the UK government plans to replace these with Local Involvement Networks (LINks) (Department of Health 2006a). This reflects a belief on the part of policymakers that:

NHS organisations, with their social care colleagues, need to have more effective and systematic ways of finding out what people want and need from their services. They need to reach out to those people whose needs are the greatest, to people who do not normally get involved and to people who find it hard to give their views.

To ensure that voices are heard at an individual level, within the NHS there is the Patient Advice and Liaison Service (PALS; http://www.pals.nhs.uk/), which was introduced to ‘ensure that the NHS listens to patients, their relatives, carers and friends, and answers their questions and resolves their concerns as quickly as possible’ (Patient Advice and Liaison Service 2007). While the bodies involved and their jobs are dynamic and the sketch presented here simply represents the current situation at the time of writing, the focus on getting patients’ needs taken seriously in the health services remains at the heart of policy and practice for the foreseeable future, and communication will play a central role in this process.

Telehealth and nursing

The American Telemedicine Association (2006) defines telemedicine as ‘the use of medical information exchanged from one site to another via electronic communications to improve patients’ health status’. Telehealth covers a variety of activities in which information and communication technologies play a part. The term:

is often used to encompass a broader definition of remote health care that may not involve clinical services. Video conferencing, transmission of still images, e-health including patient portals, remote monitoring of vital signs, continuing medical education, and nursing call centers are all considered part of telemedicine and telehealth.

This can involve activities as simple as the use of the telephone to real-time monitoring of vital signs and online consultations. In the case of videolinks, a nurse can, for example, conduct an examination of a patient while at the same time being in audiovisual communication with other specialists who may assess the patient’s problems remotely. In the UK, there is acknowledgement of the benefits of so called e-medicine, especially in rural areas where there may be isolated or elderly clients. However, barriers can be encountered, especially where there is limited training, or where providers baulk at the initial cost of setting up facilities and associated increases in workload (Richards et al 2005).

Kinds of talk in healthcare settings

Language can be a means of socializing a client into a particular kind of role, as a patient, a victim, as someone who is in pain or as someone who is incapable. There has been considerable research about the role of language styles and plot structures in enabling the roles of healthcare professionals and patients to be performed. Proctor et al (1996) studied how nurses in a trauma centre in a US hospital talked to injured patients. By video-taping interactions between nurses and patients in pain, the ‘Comfort talk register’ was identified, which included the following functions:

• Holding on was conducted through the use of phrases like ‘Big girl’, ‘You’re doing great’, ‘Count to three’. This served to praise, to let the patient know they can get through, to support, to instruct or distract the patient.

• Assessing involved ‘How are you?’ questions or giving the patient information – ‘You’re in the emergency room’. These involved getting information, explaining the situation or validating and confirming the patient’s input.

• Informing were statements like ‘It’s gonna hurt’ or ‘We’ll be inserting a catheter’, i.e. warning the patient or explaining procedures.

• Caring included statements like ‘Relax’ or ‘OK sweetie’ or ‘It does hurt, doesn’t it?’, i.e. reassuring, empathic or caring comments (Proctor et al 1996: 1673).

The authors suggest that because comfort talk is regularly used, it has a rhythmical, sing-song quality aimed at getting patients to endure the situation for longer. This highlights the importance of the style and content of communication in managing treatment.

The negative use of communication

As nurses deal with clients, some features of their language can be a source of complaint. Caregivers interacting with elderly clients have been observed using high-pitched baby talk, controlling institutional talk, short utterances, simple grammatical structures, interrogatives (questions) and imperatives (commands) (Ambady et al 2002). Moreover, there is some evidence to suggest that use of patronizing speech styles does not depend on the status of the patient – the confused are no more likely to be patronized than those who are alert and oriented. Rather, the speech style seemed to depend on the attitudes of the caregiver (Caporael et al 1983). The features of speech and non-verbal behaviour – for example high pitch, pats on the shoulder and expressions like ‘That’s a good girl’ – are perceived by the elderly patients themselves as patronizing, and are seen as unfavourable by observers (Ryan et al 1994). It is important that those working with elderly people are aware of such behaviour and that instruction is incorporated into the education of caregivers (Ryan et al 1994).

Anger in healthcare settings is a major problem. In the Healthcare Commission’s NHS survey for 2006 (Healthcare Commission 2007a) 11% of staff had experienced physical violence and 26% had experienced bullying, harassment or abuse from patients or their relatives. Hollinworth et al (2005) note that there are many things that nurses can do to avert potentially angry responses.

To illustrate this let us consider a classic example from Albert Robillard (1996), a sociologist who suffers multiple disabilities arising from motor neurone disease, movingly describing the effects of patronizing talk. He illustrates people’s responses to his anger at this kind of mistreatment thus:

The response of my interlocutors to my visible anger ranges from ‘I did not know you could hear’, ‘I didn’t know you could think!’, ‘Most of my patients are stroke victims and have trouble understanding me’ to ‘Oh, I am sorry, I won’t do it again.’ Most react to my outburst by ignoring me, leading me to see the ignoral as a further documentary reading of my symptomatology by my interlocutor.

It is a toss-up if my harsh reaction will change the course of interaction. Frequently those who say ‘I did not know you could …’, or ‘I am sorry, I will not do it again’ go back to exclusionary practices in a few moments.

(Robillard 1996: 19)

Hollinworth et al (2005) note fragmentary care from a variety of practitioners who may each seem ill prepared to deal with patients’ problems. Also, practitioners who talk down to patients or who talk among themselves can contribute to feelings of exclusion on the part of patients and carers and may prompt an angry response. Equally, fear, physical illness and disability, confusion and pain may all present as anger.

Institutional care encourages dependency, by means of both open (overt) and secret or disguised (covert) strategies on the part of care staff (Ryan & Scullion 2000). Although the situation is changing slowly, being a ‘good patient’ traditionally involved being passive, compliant and docile. The language of the institution is thought to be more important in producing dependency than the disability itself. Moreover, despite the ethic of care in such institutions, the experience of being cared for is often profoundly dehumanizing:

Older residents must adapt to a new set of routines, expectations and rules, frequently compromising or abandoning their own lifetime preferences, habits and needs. Further, they must make these adaptations from the socially inferior or less powerful role of resident or patient.

(Ryan et al 1994: 238)

The role of language may be to offer comfort and to enlist clients in the rituals of health care in a way that will ultimately benefit them. It is important, however, to be aware of how language might just as easily patronize or incapacitate clients and place them in a position where they are disadvantaged.

THE ROLE OF CULTURE IN NARRATIVES OF HEALTH AND ILLNESS

Fundamental ideas about medicine are embedded in culture and language. Within the UK in the 21st century, most people think that they know what a sick person is. Everyday complaints like the common cold and gastrointestinal upsets have a set of symptoms that are expected to co-occur. However, history suggests that the way illness is defined depends a great deal on recent changes in patterns of sickness and health. Contemporary illnesses are different from those described in the 18th century – people no longer claim to suffer from ‘seizures of the bowels’ or ‘rising of the lights’. Nevertheless, in all centuries, the coherence of an illness is an important part of the sufferer’s experience of it. Concern with narrative emerges from the everyday observation that when we find out about someone, we usually do so by means of a story that they tell or which someone else tells about them. These stories are important because they do not merely describe experience but constitute or make it. Nurses narrate both their own stories of care and the stories told to them by clients. This does not mean that the stories nurses tell are pure fictions, but much of what happens between nurses and patients is to do with narration. This idea has been developed in psychology, sociology, anthropology and in the study of medical and nursing activities and the experiences of clients.

Consider how much of your work depends on the stories you tell about yourself and about those for whom you care. To make this exercise a little more concrete, you might like to think about the following examples: physical problems – broken femur, appendicitis; psychological problems – depression, anxiety; life course changes – birth, hospice care.

• What kinds of events are these problems likely to involve?

• What might one encounter as a nurse?

• How do these ‘stories’ about clients’ problems influence the kind of care we make available?

• Write up your experiences for your portfolio and discuss with your peer group or personal tutor.

Narratives also reflect the interests of the teller. For example, Hyden (1995) describes how in cases of domestic violence, male perpetrators favour words that emphasize purpose (why they acted as they did) whereas female partners emphasize agency (how they were beaten) and the physical and emotional consequences. This kind of storytelling reveals another important feature – the communicators are often at pains to manage their ‘stake’ and ‘interest’ in the piece. A critical comment about a patient may be prefaced with the claim ‘I usually try to be on the patient’s side, but …’. Everyday speech is littered with similar examples. Homophobic comments are often accompanied by statements like ‘Some of my best friends are gay’ or potential accusations of ethnic prejudice are headed off with ‘I’m not racist but …’. In narratives of illness encountered by nurses, it is important to consider the role that culture has in helping to make sense of these phenomena. In European or North American white majority cultures, the degree of correspondence between the stories told by clients and professionals makes it easy to take signs, symptoms, syndromes and illnesses for granted. However, it is important to realize that if this cultural frame of reference is moved, the problems people express may seem at odds with dominant Western medical notions of health and illness.

Consider the comments of a woman of South Asian parentage speaking after her nephew had died in an accident: ‘My heart is weak. I am ill with too much thinking … the blood becomes weaker with worry … I have the illness of sorrows’ (Fenton & Sadiq-Sangster 1996).

• Can this account be repackaged by the interviewer as depression, or does labelling what she is suffering as depression lose some of the culturally important information which could lead to her being helped?

• Do existing forms, records and checklists that you use in your practice allow for the inclusion of such accounts? If not, why not?

• How could healthcare practice be broadened to include more of the experience of other cultures?

CARE DELIVERY KNOWLEDGE

Much of nursing care delivery is about communicating in day-to-day spoken and written interactions with members of the healthcare team, patients and relatives. This might take place in such activities as assessment and care planning, information giving, teaching and health promotion, record keeping, dealing with communication difficulties and challenging communication, and in counselling and building therapeutic relationships. These areas will be explored further, but first, we must introduce models for communication approaches.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree