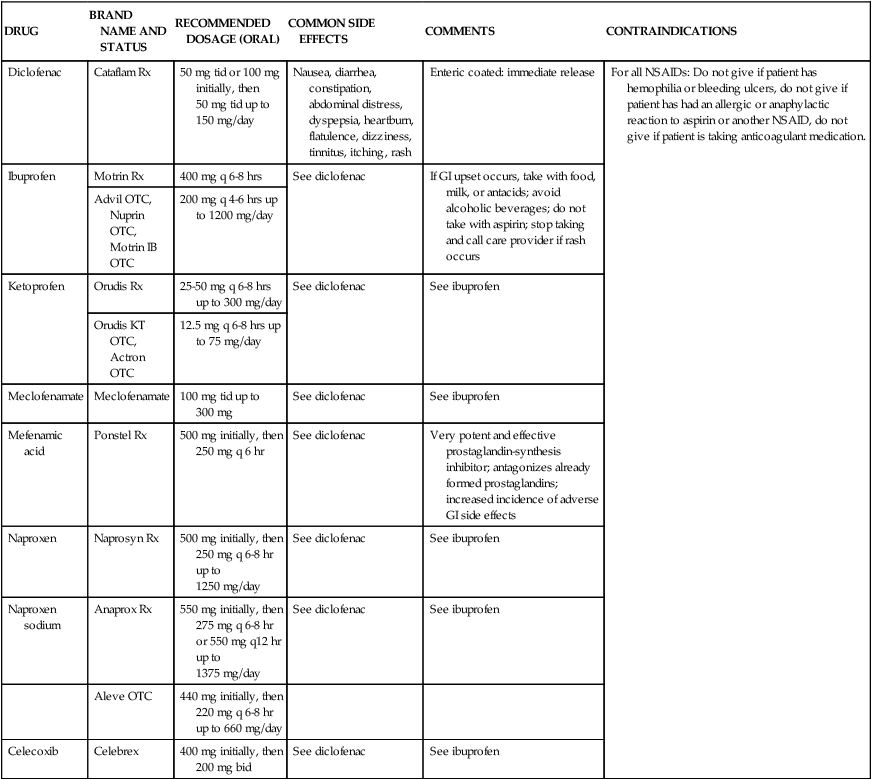

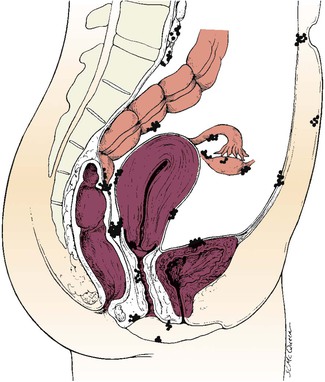

• Differentiate the signs and symptoms among common menstrual disorders. • Develop a nursing care plan for the woman with primary dysmenorrhea. • Outline patient teaching about premenstrual syndrome. • Relate the pathophysiologic aspects of endometriosis to associated symptoms. • Consider the use of alternative therapies for menstrual disorders. • Describe the prevention of sexually transmitted infections in women. • Differentiate the signs, symptoms, diagnoses, and management of women with bacterial and viral sexually transmitted infections. • Differentiate the signs, symptoms, and management of selected vaginal infections. • Explain the effects on and management of pregnant women who have human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. • Review the principles of infection control, including Standard Precautions and precautions for invasive procedures. • Discuss the pathophysiologic features of selected benign breast conditions and malignant neoplasms of the breasts found in women. • Discuss the emotional effects of benign and malignant neoplasms. • Compare alternatives for treatment for the woman with a lump in her breast. Amenorrhea, the absence or cessation of menstrual flow, is a clinical sign of a variety of disorders. Although the criteria used to determine when amenorrhea is a clinical problem are not universal, you should evaluate the following circumstances: (1) the absence of both menarche and secondary sexual characteristics by age 14; (2) the absence of menses by age Amenorrhea is most commonly a result of pregnancy, although it may occur from any defect or interruption in the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian-uterine axis (see Chapter 2). It may also result from anatomic abnormalities; other endocrine disorders, such as hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism; chronic diseases, such as type 1 diabetes; medications, such as phenytoin (Dilantin); eating disorders; strenuous exercise; emotional stress; and oral contraceptive use. Hypogonadotropic amenorrhea reflects a problem in the central hypothalamic-pituitary axis. In rare instances a pituitary lesion or genetic inability to produce FSH and LH is at fault. More commonly, it results from hypothalamic suppression as a result of two principal influences: stress (in the home, school, or workplace) or a body fat-to-lean ratio that is inappropriate for an individual woman, especially during a normal growth period (Lobo, 2007d). Research has demonstrated a biologic basis for the relationship of stress to physiologic processes. Exercise-associated amenorrhea can occur in women undergoing vigorous physical and athletic training and is associated with many factors, including body composition (height, weight, and percentage of body fat); type, intensity, and frequency of exercise; nutritional status; and the presence of emotional or physical stressors (Lobo). Amenorrhea is one of the classic signs of anorexia nervosa, and the interrelatedness of disordered eating, amenorrhea, and altered bone mineral density has been described as the female athlete triad (Lebrun, 2007). Calcium loss from bone, comparable to that seen in postmenopausal women, may occur with this type of amenorrhea. If a woman’s exercise program is contributing to her amenorrhea, several options exist for management. She may decide to decrease the intensity or duration of her training, if possible, or to gain some weight, if appropriate. Accepting this alternative is often difficult for women who are committed to a strenuous exercise regimen. Some young women athletes do not understand the consequences of low bone density or osteoporosis; nurses can point out the connection between low bone density and stress fractures. If the woman continues to have low estrogen levels, instituting estrogen therapy, as well as calcium supplementation for osteoporosis prevention, is sometimes necessary (Lobo, 2007d). Cyclic perimenstrual pain and discomfort (CPPD) is a concept developed by a nurse science team for a research project for the Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses (AWHONN) (AWHONN, 2003; Collins Sharp, Taylor, Thomas, Killeen, & Dawood, 2002). This concept includes dysmenorrhea, premenstrual syndrome, and premenstrual dysphoric disorder, as well as symptom clusters that occur before and after the menstrual flow starts. CPPD is a health problem that can have a significant impact on the quality of life for a woman. The following discussion focuses on the three main conditions of CPPD. Dysmenorrhea, pain during or shortly before menstruation, is one of the most common gynecologic problems in women of all ages. Many adolescents have dysmenorrhea in the first 3 years after menarche. Young adult women ages 17 to 24 years are most likely to report painful menses. Approximately 75% of women report some level of discomfort associated with menses, and approximately 15% report severe dysmenorrhea (Lentz, 2007b); however, the amount of disruption in women’s lives is difficult to determine. Researchers have estimated that up to 10% of women with dysmenorrhea have severe enough pain to interfere with their functioning for 1 to 3 days a month. Menstrual problems, including dysmenorrhea, are relatively more common in women who smoke and who are obese. Severe dysmenorrhea is also associated with early menarche, nulliparity, and stress (Lentz). Traditionally dysmenorrhea is differentiated as primary or secondary. Symptoms usually begin with menstruation, although some women have discomfort several hours before onset of flow. The range and severity of symptoms are different from woman to woman and from cycle to cycle in the same woman. Symptoms of dysmenorrhea may last several hours or several days. Primary dysmenorrhea is a condition associated with ovulatory cycles. Research has shown that primary dysmenorrhea has a biochemical basis and arises from the release of prostaglandins with menses. During the luteal phase and subsequent menstrual flow, prostaglandin F2-alpha (PGF2a) is secreted. Excessive release of PGF2a increases the amplitude and frequency of uterine contractions and causes vasospasm of the uterine arterioles, resulting in ischemia and cyclic lower abdominal cramps. Systemic responses to PGF2a include backache, weakness, sweats, gastrointestinal symptoms (anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea), and central nervous system symptoms (dizziness, syncope, headache, and poor concentration). Pain usually begins at the onset of menstruation and lasts 8 to 48 hours (Lentz, 2007b). Often, you can offer more than one alternative for alleviating menstrual discomfort and dysmenorrhea, which gives women options to try and decide which works best for them. Medications used to treat primary dysmenorrhea include prostaglandin synthesis inhibitors, primarily nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (Lentz, 2007b) (Table 3-1). NSAIDs are most effective if started several days before menses or at least by the onset of bleeding. All NSAIDs have potential gastrointestinal side effects, including nausea, vomiting, and indigestion. Warn all women taking NSAIDs to report dark-colored stool because this may be an indication of gastrointestinal bleeding. TABLE 3-1 Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Agents Used to Treat Dysmenorrhea GI, Gastrointestinal; NSAID, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug; OTC, over the counter. Data from Facts and Comparisons. (2012). Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. www.factsandcomparisons.com; Lentz, G.M. (2012). Primary and secondary dysmenorrhea, premenstrual syndrome, and premenstrual dysphoric disorder: etiology, diagnosis, and management. In Lentz, G.M., Lobo, R.A., Gershenson, D.M., et al. (Eds.). Comprehensive gynecology (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Mosby; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2008). Medication guide for nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). www.fda.gov/CDER/drug/infopage/COX2/NSAIDmedguide.htm. OCPs prevent ovulation and can decrease the amount of menstrual flow, which can decrease the amount of prostaglandin, thus decreasing dysmenorrhea. There is evidence that combined OCPs can effectively treat dysmenorrhea (Lentz, 2007b). OCPs may be used in place of NSAIDs if the woman wants oral contraception and has primary dysmenorrhea. OCPs have side effects, and women who do not need or want them for contraception may not wish to use them for dysmenorrhea. OCPs also may be contraindicated for some women. TABLE 3-2 Herbal Therapies for Menstrual Disorders Sources: Bascom, A. (2002). Incorporating herbal medicine into clinical practice. Philadelphia: FA Davis; Fugh-Berman, A., & Awang, D. (2001). Black cohosh. Alternative Therapies in Women’s Health, 39(11), 81-85; Dog, L. (2001). Conventional and alternative treatments for endometriosis. Alternative Therapies, 7(6), 50-56; Stevinson, C., & Ernst, E. (2001). Complementary/alternative therapies for premenstrual syndrome: A systemic review of randomized controlled trials. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 185(1), 227-235. Approximately 30% to 80% of women experience mood or somatic symptoms (or both) that occur with their menstrual cycles (Lentz, 2007b). Establishing a universal definition of premenstrual syndrome (PMS) is difficult, given that so many symptoms have been associated with the condition, and at least two different syndromes have been recognized: PMS and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). PMDD is a more severe variant of PMS in which 3% to 8% of women have marked irritability, dysphoria, mood lability, anxiety, fatigue, appetite changes, and a sense of feeling overwhelmed (Lentz, 2007b). A diagnosis of PMS is made when the following criteria are met (American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology [ACOG], 2000; AWHONN, 2003): • Symptoms consistent with PMS occur in the luteal phase and resolve within a few days of menses onset. • Symptom-free period occurs in the follicular phase. • Symptoms have a negative impact on some aspect of a woman’s life. • Other diagnoses that better explain the symptoms have been excluded. For a diagnosis of PMDD, the following criteria must be met (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000): • Five or more affective and physical symptoms are present in the week before menses and are absent in the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle. • At least one of the symptoms is irritability, depressed mood, anxiety, or emotional lability. • Symptoms interfere markedly with work or interpersonal relationships. • Symptoms are not caused by an exacerbation of another condition or disorder. • These criteria must be confirmed by prospective daily ratings for at least two menstrual cycles (APA, 2000). The causes of PMS and PMDD are unknown. Researchers have theorized that PMS has a significant psychologic component or may result from cultural beliefs that lead to the menstrual cycle being associated with a variety of negative reactions. In reality, PMS is most likely not a single disorder but is rather a collection of different problems (Lentz, 2007b). Much controversy exists regarding PMS. The existence, diagnosis, and causes of PMS are controversial. Explore current feminist, medical, and social science literature for more information on these topics. Education is an important component of the management of PMS. Nurses can advise women that self-help modalities often result in significant symptom improvement. Women have found a significant number of complementary and alternative therapies to be useful in managing the symptoms of PMS. Diet and exercise changes are a useful way to begin and provide symptom relief for some women. Suggest that women refrain from smoking and limit their consumption of refined sugar (less than 5 tbsp/day), salt (less than 3 g/day), red meat (up to 3 oz/day), alcohol (less than 1 oz/day), and caffeinated beverages. Also, encourage them to include whole grains, legumes, seeds, nuts, vegetables, fruits, and vegetable oils in their diet. Three small-to-moderate-sized meals and three small snacks a day that are rich in complex carbohydrates and fiber help reduce symptoms (Lentz, 2007b). Use of natural diuretics (see section on dysmenorrhea management) also helps reduce fluid retention as well. Nutritional supplements may assist in symptom relief. Calcium (1000-1200 mg daily), magnesium (300-400 mg daily), and vitamin B6 (100-150 mg daily) have been reported to be moderately effective in relieving symptoms, have few side effects, and are safe. Regular exercise (aerobic exercise three to four times a week), especially in the luteal phase, is widely recommended for relief of PMS symptoms (Lentz, 2007b). A monthly program that varies in intensity and type of exercise according to PMS symptoms is best. Women who exercise regularly seem to have less premenstrual anxiety than do nonathletic women. Researchers believe aerobic exercise increases beta-endorphin levels to offset symptoms of depression and elevate mood. Nurses can explain the relationship between cyclic estrogen fluctuation and changes in serotonin levels, that serotonin is one of the brain chemicals that assist in coping with normal life stresses, and how the different management strategies recommended help maintain serotonin levels. Counseling, in the form of support groups or individual or couple counseling, is helpful. Stress-reduction techniques also may assist with symptom management (Lentz, 2007b). If these strategies do not provide significant symptom relief in 1 to 2 months, medication is often begun. Many medications have been used in treatment of PMS, but no single medication alleviates all PMS symptoms. Medications often used in the treatment of PMS include diuretics, prostaglandin inhibitors (NSAIDs), progesterone, and OCPs. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors such as Fluoxetine (Sarafem or Prozac) are U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved agents for PMS. Use of these medications results in a decrease in emotional symptoms, especially depression (Lentz, 2007b). Endometriosis is the presence and growth of endometrial tissue outside of the uterus. The tissue may be implanted on the ovaries, cul-de-sac, uterine ligaments, rectovaginal septum, sigmoid colon, pelvic peritoneum, cervix, or inguinal area (Fig. 3-1). Endometrial lesions have been found in the vagina and in surgical scars; on the vulva, perineum, and bladder; and in sites far from the pelvic area, such as the thoracic cavity, gallbladder, and heart. A chocolate cyst is a cystic area of endometriosis in the ovary. Old blood causes the dark coloring of the cyst’s contents. Endometriosis is a common gynecologic problem, affecting from 6% to 10% of women of reproductive age (Lobo, 2007b). Although the condition usually develops in the third or fourth decade of life, endometriosis occurs in approximately 10% of adolescents with disabling pelvic pain or abnormal vaginal bleeding (ACOG, 2005). The condition is found equally in Caucasian and African-American women, is slightly more prevalent in Asian women, and may have a familial tendency for development (Lobo, 2007b). Endometriosis may worsen with repeated cycles, or it may remain asymptomatic and undiagnosed, eventually disappearing after menopause. Symptoms vary among women, from nonexistent to incapacitating. Severity of symptoms can change over time and may be disconnected from the extent of the disease. The major symptoms of endometriosis are dysmenorrhea, infertility, and deep pelvic dyspareunia (painful intercourse). Women also experience chronic noncyclic pelvic pain, pelvic heaviness, or pain radiating into the thighs. Many women report bowel symptoms such as diarrhea, pain with defecation, and constipation secondary to avoiding defecation because of the pain. Less common symptoms include abnormal bleeding (hypermenorrhea, menorrhagia, or premenstrual staining) and pain during exercise as a result of adhesions (Lobo, 2007b). Hormonal antagonists that suppress ovulation and reduce endogenous estrogen production and subsequent endometrial lesion growth are currently used to treat mild to severe endometriosis in women who wish to become pregnant at a future time. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist therapy (leuprolide, nafarelin [Synarel], goserelin acetate [Zoladex]) acts by suppressing pituitary gonadotropin secretion. FSH and LH stimulation to the ovary declines noticeably, and ovarian function decreases significantly. The hypoestrogenism results in hot flashes in almost all women. In addition, minor bone loss sometimes occurs, most of which is reversible within 12 to 18 months after the medication is stopped. Leuprolide (3.75 mg intramuscular injection given once a month) or nafarelin (200 mcg administered twice daily by nasal spray) are both effective and well tolerated. Both medications reduce endometrial lesions and pelvic pain associated with endometriosis and have posttreatment pregnancy rates similar to that of danazol therapy (Lobo, 2007b). Common side effects of these drugs are similar to those of natural menopause—hot flashes and vaginal dryness. Some women report headaches and muscle aches. These medications are not given to adolescents as the hypoestogenic state that occurs can affect bone mineralization (ACOG, 2005). Danazol (Danocrine), a mildly androgenic synthetic steroid, suppresses FSH and LH secretion, thus producing anovulation with resulting decreased secretion of estrogen and progesterone and regression of endometrial tissue. Bothersome side effects include masculinizing traits in the woman—weight gain, edema, decreased breast size, oily skin, hirsutism, and deepening of the voice—all of which often disappear when treatment is discontinued. Other side effects are amenorrhea, hot flashes, vaginal dryness, insomnia, and decreased libido. Some women report migraine headaches, dizziness, fatigue, and depression. In addition, some women experience decreases in bone density that are only partially reversible. Danazol should never be prescribed when pregnancy is suspected, and contraception should be used with it because ovulation may not be suppressed. Danazol can produce pseudohermaphroditism in female fetuses. The drug is contraindicated in women with liver disease and should be used with caution in women with cardiac and renal disease (Lobo, 2007b). Surgical intervention is often needed for severe, acute, or incapacitating symptoms. A woman’s age, desire for children, and location of the disease influence decisions regarding the extent and type of surgery. For women who do not want to preserve their ability to have children, the only definite cure is hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) (total abdominal hysterectomy [TAH] with BSO). In women who are in their childbearing years and who want children if the disease does not prevent pregnancy, surgery or laser therapy is used to carefully remove as much endometrial tissue as possible to maintain reproductive function (Lobo, 2007b). Short of TAH with BSO, endometriosis recurs in approximately 40% to 50% of women, regardless of the form of treatment. Therefore, for many women, endometriosis is a chronic disease with conditions such as chronic pain or infertility. Counseling and education are critical components of nursing care of women with endometriosis. Women need an honest discussion of treatment options with potential risks and benefits of each option reviewed. Because pelvic pain is a subjective, personal experience that can be frightening, support is important. Sexual dysfunction resulting from dyspareunia may be present and may necessitate referral for counseling. Some locations have support groups for women with endometriosis. The nursing care measures discussed in the section on dysmenorrhea are appropriate for managing chronic pelvic pain associated with endometriosis (see Nursing Care Plan). Uterine leiomyomas (fibroids or myomas) are a common cause of menorrhagia. Fibroids are benign tumors of the smooth muscle of the uterus with an unknown cause. Fibroids occur in approximately one fourth of women of reproductive age; the incidence of fibroids is higher in African-American women than in Caucasian, Asian, or in Hispanic women (Katz, 2007). Other uterine growths ranging from endometrial polyps to adenocarcinoma and endometrial cancer are common causes of heavy menstrual bleeding, as well as intermenstrual bleeding. Treatment for menorrhagia depends on the cause of the bleeding. If the bleeding is related to contraceptive method (e.g., an IUD), provide factual information and reassurance and discuss other contraceptive options. If bleeding is related to the presence of fibroids, the degree of disability and discomfort associated with the fibroids and the woman’s plans for childbearing will influence treatment decisions. Treatment options include medical and surgical management. Most fibroids can be monitored by frequent examinations to judge growth, if any, and correction of anemia, if present. Warn women with metrorrhagia to avoid using aspirin because of its tendency to increase bleeding. Medical treatment is directed toward temporarily reducing symptoms, shrinking the myoma, and reducing its blood supply (Katz, 2007). This reduction is often accomplished with the use of a GnRH agonist. If the woman wishes to retain childbearing potential, a myomectomy may be performed. Myomectomy, or removal of the tumors only, is particularly difficult if multiple myomas must be removed. If the woman does not want to preserve her childbearing function, or if she has severe symptoms (severe anemia, severe pain, considerable disruption of lifestyle), uterine artery embolization (procedure that blocks blood supply to fibroid), endometrial ablation (laser surgery or electrocoagulation), or hysterectomy (removal of uterus) may be performed. Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) is any form of uterine bleeding that is irregular in amount, duration, or timing and is not related to regular menstrual bleeding. Box 3-1 lists possible causes of AUB. Although often used interchangeably, the terms AUB and dysfunctional uterine bleeding (DUB) are not synonymous. DUB is a subset of AUB defined as “excessive uterine bleeding with no demonstrable organic cause (genital or extragenital)” (Lobo, 2007a, p. 915). DUB is most commonly caused by anovulation. When no surge of LH occurs, or if insufficient progesterone is produced by the corpus luteum to support the endometrium, it will begin to involute and shed. This process most often occurs at the extremes of a woman’s reproductive years—when the menstrual cycle is just becoming established at menarche or when it draws to a close at menopause. DUB also occurs with any condition that gives rise to chronic anovulation associated with continuous estrogen production. Such conditions include obesity, hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism, polycystic ovarian syndrome, and any of the endocrine conditions discussed in the sections on amenorrhea and oligomenorrhea. A diagnosis of DUB is made only after ruling out all other causes of abnormal menstrual bleeding (Lentz, 2007a). The most effective medical treatment of acute bleeding episodes of DUB is administration of oral or intravenous estrogen. Dilation and curettage may be done if the bleeding has not stopped in 12 to 24 hours. An oral conjugated estrogen and progestin regimen is usually given for at least 3 months. If the woman wants contraception, she should continue to take OCPs. If she has no need for contraception, the treatment may be stopped to assess the woman’s bleeding pattern. If her menses does not resume, a progestin regimen (e.g., medroxyprogesterone, 10 mg each day for 10 days before the expected date of her menstrual period) may be prescribed after ruling out pregnancy. This is done to prevent persistent anovulation with chronic unopposed endogenous estrogen hyperstimulation of the endometrium, which can result in eventual atypical tissue changes (Lobo, 2007a). If hormonal therapy does not control the recurrent, heavy bleeding, ablation of the endometrium through laser treatment may be performed (Lobo, 2007a). Nursing roles include informing women of their options, counseling and providing education as indicated, and referring to the appropriate specialists and health care services. Infections of the reproductive tract can occur throughout a woman’s life and are often the cause of significant reproductive morbidity, including ectopic pregnancy and tubal factor infertility (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2007a). The direct economic costs of these infections can be substantial, and the indirect cost is equally overwhelming. Some consequences of maternal infection, such as infertility, last a lifetime. The emotional costs may include damaged relationships and lowered self-esteem. Sexually transmitted infections are infections or infectious disease syndromes transmitted primarily by sexual contact (Box 3-2). The term sexually transmitted infection includes more than 25 infectious organisms that are transmitted through sexual activity and the dozens of clinical syndromes that they cause. STIs are among the most common health problems in the United States today, with an estimated 19 million people in the United States being infected with STIs every year (CDC, 2007c). Later, this chapter discusses the most common STIs in women. Chapter 21 discusses effects on pregnancy and the fetus. Chapter 24 discusses neonatal effects.

Common Concerns

Menstrual Problems

Amenorrhea

, regardless of presence of normal growth and development (primary amenorrhea); or (3) a 6- to 12-month cessation of menses after a period of menstruation (secondary amenorrhea) (Speroff & Fritz, 2005).

, regardless of presence of normal growth and development (primary amenorrhea); or (3) a 6- to 12-month cessation of menses after a period of menstruation (secondary amenorrhea) (Speroff & Fritz, 2005).

Management

Cyclic Perimenstrual Pain and Discomfort

Dysmenorrhea

Primary dysmenorrhea

Management.

![]()

![]() Heat (heating pad or hot bath) minimizes cramping by increasing vasodilation and muscle relaxation and minimizing uterine ischemia. Massaging the lower back can reduce pain by relaxing paravertebral muscles and increasing the pelvic blood supply. Soft, rhythmic rubbing of the abdomen (effleurage) is useful because it provides a distraction and an alternative focal point. Biofeedback, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), progressive relaxation, Hatha yoga, acupuncture, and meditation are also used to decrease menstrual discomfort, although evidence is insufficient to determine their effectiveness (Lentz, 2007b).

Heat (heating pad or hot bath) minimizes cramping by increasing vasodilation and muscle relaxation and minimizing uterine ischemia. Massaging the lower back can reduce pain by relaxing paravertebral muscles and increasing the pelvic blood supply. Soft, rhythmic rubbing of the abdomen (effleurage) is useful because it provides a distraction and an alternative focal point. Biofeedback, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), progressive relaxation, Hatha yoga, acupuncture, and meditation are also used to decrease menstrual discomfort, although evidence is insufficient to determine their effectiveness (Lentz, 2007b).

DRUG

BRAND NAME AND STATUS

RECOMMENDED DOSAGE (ORAL)

COMMON SIDE EFFECTS

COMMENTS

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Diclofenac

Cataflam Rx

50 mg tid or 100 mg initially, then 50 mg tid up to 150 mg/day

Nausea, diarrhea, constipation, abdominal distress, dyspepsia, heartburn, flatulence, dizziness, tinnitus, itching, rash

Enteric coated: immediate release

For all NSAIDs: Do not give if patient has hemophilia or bleeding ulcers, do not give if patient has had an allergic or anaphylactic reaction to aspirin or another NSAID, do not give if patient is taking anticoagulant medication.

Ibuprofen

Motrin Rx

400 mg q 6-8 hrs

See diclofenac

If GI upset occurs, take with food, milk, or antacids; avoid alcoholic beverages; do not take with aspirin; stop taking and call care provider if rash occurs

Advil OTC, Nuprin OTC, Motrin IB OTC

200 mg q 4-6 hrs up to 1200 mg/day

Ketoprofen

Orudis Rx

25-50 mg q 6-8 hrs up to 300 mg/day

See diclofenac

See ibuprofen

Orudis KT OTC, Actron OTC

12.5 mg q 6-8 hrs up to 75 mg/day

Meclofenamate

Meclofenamate

100 mg tid up to 300 mg

See diclofenac

See ibuprofen

Mefenamic acid

Ponstel Rx

500 mg initially, then 250 mg q 6 hr

See diclofenac

Very potent and effective prostaglandin-synthesis inhibitor; antagonizes already formed prostaglandins; increased incidence of adverse GI side effects

Naproxen

Naprosyn Rx

500 mg initially, then 250 mg q 6-8 hr up to 1250 mg/day

See diclofenac

See ibuprofen

Naproxen sodium

Anaprox Rx

550 mg initially, then 275 mg q 6-8 hr or 550 mg q12 hr up to 1375 mg/day

See diclofenac

See ibuprofen

Aleve OTC

440 mg initially, then 220 mg q 6-8 hr up to 660 mg/day

Celecoxib

Celebrex

400 mg initially, then 200 mg bid

See diclofenac

See ibuprofen

![]()

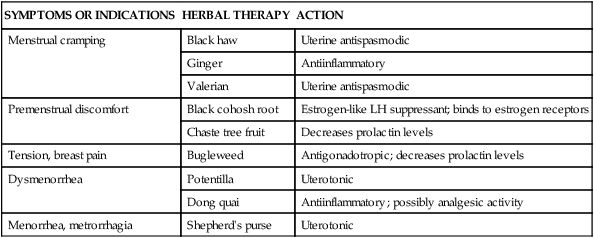

![]() Alternative and complementary therapies are increasingly popular and used in developed countries. Therapies such as acupuncture, acupressure, biofeedback, desensitization, hypnosis, massage, reiki, relaxation exercises, and therapeutic touch have been used to treat pelvic pain (Dehlin & Schuiling, 2006). Herbal preparations have long been used for the management of menstrual problems, including dysmenorrhea (Table 3-2). Herbal medicines can be valuable in treating dysmenorrhea; however, women must understand that these therapies are not without potential toxicity and may cause drug interactions. Women should use herbal preparations from well-established companies. It is also important to know that research is limited about the effectiveness of use (Dehlin & Schuiling, 2006).

Alternative and complementary therapies are increasingly popular and used in developed countries. Therapies such as acupuncture, acupressure, biofeedback, desensitization, hypnosis, massage, reiki, relaxation exercises, and therapeutic touch have been used to treat pelvic pain (Dehlin & Schuiling, 2006). Herbal preparations have long been used for the management of menstrual problems, including dysmenorrhea (Table 3-2). Herbal medicines can be valuable in treating dysmenorrhea; however, women must understand that these therapies are not without potential toxicity and may cause drug interactions. Women should use herbal preparations from well-established companies. It is also important to know that research is limited about the effectiveness of use (Dehlin & Schuiling, 2006).

SYMPTOMS OR INDICATIONS

HERBAL THERAPY

ACTION

Menstrual cramping

Black haw

Uterine antispasmodic

Ginger

Antiinflammatory

Valerian

Uterine antispasmodic

Premenstrual discomfort

Black cohosh root

Estrogen-like LH suppressant; binds to estrogen receptors

Chaste tree fruit

Decreases prolactin levels

Tension, breast pain

Bugleweed

Antigonadotropic; decreases prolactin levels

Dysmenorrhea

Potentilla

Uterotonic

Dong quai

Antiinflammatory; possibly analgesic activity

Menorrhea, metrorrhagia

Shepherd’s purse

Uterotonic

Premenstrual Syndrome and Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder

Management

![]() Daily supplements of evening primrose oil are also useful in relieving breast symptoms with minimal side effects. Other herbal therapies have long been used to treat PMS; Table 3-2 lists specific suggestions.

Daily supplements of evening primrose oil are also useful in relieving breast symptoms with minimal side effects. Other herbal therapies have long been used to treat PMS; Table 3-2 lists specific suggestions.

![]() Yoga, acupuncture, hypnosis, chiropractic therapy, and massage therapy have all been reported to have a beneficial effect on PMS. Further research is needed for all of these suggested therapies.

Yoga, acupuncture, hypnosis, chiropractic therapy, and massage therapy have all been reported to have a beneficial effect on PMS. Further research is needed for all of these suggested therapies.

Endometriosis

Management

Alterations in Cyclic Bleeding

Dysfunctional uterine bleeding

Infections

Sexually Transmitted Infections