6.1 The hierarchy of research evidence

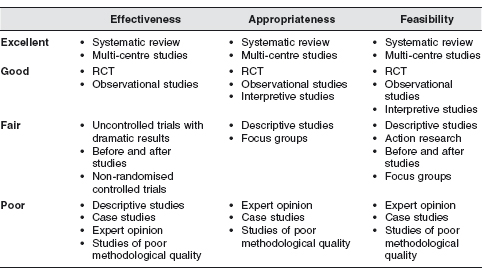

Different research designs offer different levels of certainty about the results of the research and the idea of a hierarchy of evidence has been used widely. Traditionally, hierarchies have focused on the effectiveness of an intervention or treatment and thus the randomised control trial is regarded as the best research design for producing evidence on effectiveness, with systematic reviews of a number of randomised controlled trials at the top of the hierarchy (see Table 6.1).

However, this approach has generated controversy and much discussion about where other research designs fit into the various levels. An excellent review of the topic is given by Evans (2003), who offers a broader view of the evaluation of health care interventions. He argues that the hierarchy for the effectiveness of interventions is well placed to answer such questions as: Does the intervention work? Is it better than the usual treatment? What are the harms? However, it does not include research that can offer insight into the appropriateness and feasibility of an intervention. Clearly for an intervention to be useful it must be effective, but also acceptable to the patient and feasible to incorporate into routine health care. So Evans’ proposed hierarchy may be more useful than the traditional approach if you are aiming to answer questions like:

What is the patient’s experience?

What is the patient’s experience? What outcomes does the patient view as important?

What outcomes does the patient view as important? Will the intervention be accepted by health care workers?

Will the intervention be accepted by health care workers? How can the intervention be best implemented into routine practice?

How can the intervention be best implemented into routine practice?Evans’ hierarchy is shown in Figure 6.1. This includes and shows the value of qualitative interpretive methods, but supports the idea that larger multicentre trials and systematic reviews of whatever methodology will always give the most powerful evidence. As with the traditional hierarchy, case reports, opinion, and poor quality studies are ranked lowest.

Table 6.1 The traditional hierarchy of research designs which will provide the most reliable evidence for the effectiveness of treatments.

| Rank | Methodology | Description |

| 1 | Systematic reviews and meta-analyses | A systematic review combines the results of a number of original studies which have been systematically searched out, judged on pre-defined inclusion criteria, and a synthesis of their results is produced. A meta-analysis is the combination of results from several independent trials to produce an overall result. A systematic review will often include a meta-analysis. Meta-analysis can be done on any selection of results but it is only regarded as level 1 evidence if combined with a systematic review. |

| 2 | Randomised controlled trials | Trial participants are randomly assigned to either a control group or a treatment group who receive a specific intervention. The aim is to control all other factors that may influence the effect of the intervention. |

| 3 | Cohort studies | Two or more groups of people who have a different exposure to a particular agent (like smoking, a vaccine, or type of surgery) are selected and then followed up to see what differences there are between the groups for specific outcomes. |

| 4 | Case-control studies | People with a particular condition (cases) are matched with people without the condition (controls), and differences are then examined in a retrospective analysis. |

| 5 | Cross-sectional studies and surveys | An examination of a sample of the population of interest at one point in time. Surveys often use a questionnaire or interview design. |

| 6 | Case reports | A report based on a single patient which can sometimes be collected together into a short series. |

| 7 | Expert opinion | A consensus from the experts in the field. |

| 8 | Anecdotal | Observations made through clinical practice which link a particular outcome with a particular condition or intervention. |

Figure 6.1 Hierarchy of evidence: ranking of research evidence evaluating health care interventions. David Evans (2003) Hierarchy of evidence. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 12(1), 77–84, Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Given this information you may feel that the only worthwhile research to carry out is a randomised controlled trial. However, randomised trials can be resource intensive and expensive to run and the problem may not be answerable using this design. Thus, it is important to think through carefully what design will best answer your question and aim to undertake the type of research that will provide the strongest evidence possible.

6.2 Types of research

There are two main types of research; quantitative and qualitative. Quantitative research involves the analysis of numerical data in order to explain a pre-defined hypothesis. The researcher aims to remain objective and control the conditions of the research. Qualitative research involves the analysis of words, pictures or objects in order to explore and describe a situation, process or experience. The researcher interprets the data as it unfolds during the collection process and the subjective nature of the process is embraced.

Behind these types of research are different philosophical assumptions and different approaches to examining the research question. It is beyond the scope of this book to examine these differences in detail but I would recommend that you explore them, and the Resources section will guide you to useful text books. Each type of research has its own advantages and disadvantages and will answer different types of question, which I will describe in the next sections. When making your decision, think about what your chosen method will allow you to find out and also what it will not allow you to explain.

6.3 Quantitative research

The main approaches within quantitative research are experimental and observational studies. These approaches test theories and produce numerical data which are statistically analysed. The intention is always to use a sample of a population and then make inferences about the whole population from the results of the smaller samples. Data can be collected prospectively or retrospectively; in other words from the start of the study forwards or searching back through previously collected information. Data can be explored within the study sample longitudinally, to study changes over time, or crosssectionally, to observe an occurrence at one point in time only.

6.3.1 Essential elements of experimental studies

In experimental studies we are trying to establish cause and effect. We want to show that a particular intervention causes particular effects. This is the basis of the evaluation of new therapies or procedures in health care to demonstrate effectiveness. To do this we first need to compare the new therapy (applied to the intervention group) to something else, this could be no therapy at all or the therapy that is in normal use. This is applied to the control group in the experiment.

We next need to decide what piece of information will tell us the therapy is effective and decide exactly how to measure it. This is known as the outcome, and I have discussed this elsewhere in Chapter 7, Section 7.2.6.5.

In order to ensure that the changes in the outcome measurement are due to the experimental therapy we need to consider bias – the main purpose of the experimental design is to minimise bias. Firstly, the control group should be comparable to the experimental group in all ways other than the experimental treatment. This is ideally achieved through randomisation, which ensures that the unmeasured and unmeasurable characteristics are equally distributed between the groups. Randomisation means that each person entering the study has an equal chance of being assigned to either the control or the experimental group. Randomisation is achieved through using random number tables or randomisation schedule generators on the internet (see Resources section). Despite randomisation it is still important to check that both groups are comparable, so we need to collect information about any factors that could potentially alter the response to the experimental treatment.

Another source of bias is through unconscious favouring of the intervention group over the control by both the researcher and the participants. To get round this problem, blinding is used. Single blinding means that either the researcher measuring the outcome (the assessor) does not know which group each participant is in or the participant is unaware of the group they are in. Double blinding means that neither the participant nor the researcher knows which group the participant is in. A placebo is commonly used in drug trials and sometimes in other types of therapy, and is designed so that the control group think they are receiving the same treatment as the experimental group. This allows the psychological effect of simply receiving a treatment to be taken into account. In many therapy trials it is not possible to use a placebo or achieve double blinding and in this circumstance it is crucial that every effort is made to blind the assessor to the treatments, so that the measurement of the outcome that demonstrates the effectiveness of the treatment is subject to the least bias possible.

Bias can also occur if the method of measuring the outcome is difficult and prone to variation, for example blood pressure or ultrasound measurements. This variation can be minimised by taking several measurements and using the mean of the two or three measurements; this is known as replication.

The preceding description describes the components of the randomised controlled trial, which, as I have discussed in Section 6.1, is regarded as the best form of experiment. The absence of any of these essential elements reduces the strength of the evidence produced by the research. For example, the absence of randomisation reduces the design to what is termed a quasiexperimental design, where there is a control group but the treatment is not assigned randomly. In this case it is difficult to argue that the control is similar to the experimental group and there may be differences between the two groups that could account for any effect observed. It is always better to plan a proper experimental trial and if this is not possible you need to be able to justify why a quasi-experimental approach is to be used.

6.3.2 Observational studies

Observational studies do not include a research intervention; instead participants are monitored or observed. Observational studies explore associations between factors to establish the development of a disease or condition. Examples include studies examining smoking and cancer, where people who smoke and those who do not are compared to evaluate the effects of smoking. Often observational studies are essential since the factors involved are not amenable to randomisation. We can not randomly ask people to smoke or not to smoke, or dictate a level of compliance or predict certain complications. Such studies can provide evidence of likely causes of diseases or complications, for which treatments or preventative measures can then be sought. Observational studies include cohort, case control, and cross-sectional studies. Also categorised as observational are descriptive studies such as surveys and case studies or case series. A simple description of each is given in Table 6.1.

As with experimental studies there are important elements that must be considered in each design, particularly the minimisation of bias. Selection of the sample is particularly important since it must represent the larger population as closely as possible, and in case control studies, controls must match the cases closely. Where retrospective data are being used there will be problems with recall bias and the reliability of retrospective data. Recall bias occurs when cases (people with the disease or problem) are more likely than controls to recall the factors they think might have caused the problem or when the controls under-report exposure to possible causative factors. Anyone working in health care will understand the problems with obtaining data retrospectively; often medical notes are not complete or cannot be located, and the data reported in notes are not necessarily consistent between different patients.

In prospective studies it is important to fully follow up all the original patients recruited to the study. Loss to follow up can make the results less reliable. This is a problem for all prospective studies, including experimental studies, but is particularly relevant to cohort studies, which can often involve a large number of participants over a long period of time. A similar problem, low response rate, occurs with surveys, where the validity of the results relies on a large proportion of those being surveyed actually responding.

Sections 6.3.1 and 6.3.2 provide a synopsis of the issues to think about when using particular quantitative designs. I have intentionally kept this to a minimum as research design is a huge topic and you will certainly have to obtain more detailed information on your chosen research design in other specialised texts (see Resources section). Table 6.2 summarises the most common uses of each research design and lists the advantages and disadvantages.

6.4 Qualitative research

I came to qualitative research later in my research career. Qualitative research does suffer an image problem with researchers strongly oriented to the quantitative approach; however, this is slowly changing and the value of qualitative work is being increasingly recognised. Quantitative methods fail to provide information on the context of the studied situation, and is limited by the highly structured format and a high level of control put on the situation of study.

Qualitative research can provide a much more holistic view of the problem under investigation, including information that cannot be reduced to numbers. The approach to the data collection and design of the study is more flexible, as is the subsequent analysis and interpretation of collected information, allowing the researcher to evolve their view of the problem under investigation and adapt to the changing view. The qualitative approach also allows the researcher to interact with the research subjects in their own language and on their own terms. This approach gives a deeper understanding of the problems faced in health care and can help evaluate treatment in terms of appropriateness and feasibility discussed in Section 6.1.

Table 6.2 The advantages and disadvantages of different quantitative research designs.

| Research design | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Randomised controlled trial | Provides the best form of evidence for the effectiveness of interventions. Enables the researcher to control for a variety of variables. Minimises bias. Allows determination of causality. | Needs careful planning to ensure good methodology considering randomisation, blinding, and sample size. In some cases randomisation is not ethical. Can be expensive and requires high levels of researcher input and time. Can be impractical and unfeasible if the sample sizes required are large. |

| Cohort study | Allows comparison of people who are ‘exposed’ to a particular event, procedure or risk factor, with those who are not. Can provide evidence of the factors that influence the cause or the progression of a disease. Can be useful where ethical issues prevent randomisation. | Weaker level of evidence for establishing causation. Bias is inevitably introduced due to the lack of randomisation. The cases may not be similar to the controls in important ways. Often need to be very large and have a long follow-up to allow sufficient cases of the disease of interest to occur during the study. Can be very costly to run due to the need for rigorous follow up and the large sample sizes. |

| Case control study | Allows comparison of patients with a particular disease or condition with those who have not got it. Efficient since they start with the cases and so the sample size can be kept to a minimum to demonstrate an association. Relatively easy to run. Cheaper than randomised controlled trials or cohort studies. No follow up issues. | Weaker level of evidence for establishing causation and association. Prone to bias due to recall, selection, missing retrospective data and use of inappropriate controls. |

| Cross-sectional study | Allows a snap shot of a group of individuals who have a condition and comparison with those who do not. Also useful for validation and reliability studies or screening of diagnostic tools. As data are collected currently this design does not have the issues with bias in case control studies. No follow-up issues. Relatively cheap and easy to run. | Provides weak evidence of associations. Sample selection can be difficult and needs to represent the total population. The associations identified do not allow identification of the time sequence of events. So if a group of malnourished patients were compared to a group of well nourished it is likely the malnourished would be less healthy. But are they malnourished due to ill health or has poor health occurred due to poor nutrition? |

| Survey (type of descriptive crosssectional study) | Can be used to explore a wide variety of issues such as prevalence, characteristics of a population or views and opinions. Provide descriptive data and generate hypotheses, guiding future research. Relatively cheap and easy to run. No follow up issues. It is feasible to use random samples for the total population of interest. | No evidence of associations or causality. Descriptive information only. Low response rates can limit applicability of results. Responders can differ to those who do not respond – volunteer bias. |

| Case report or case series | Provides descriptive data about a single case or several similar cases. Easy to do as part of clinical practice. Can generate hypotheses and guide future research. Can be useful to learn from very rare cases. | No evidence of associations or causality. Descriptive information only. Observation of few cases can be very misleading and due simply to chance. Contributes little to improving clinical practice. |

The philosophy behind qualitative design recognises that there may be more than one world view; different researchers can interpret the same data in different ways. From the view of a quantitative researcher this is a disadvantage, but provided the underlying philosophy is explicitly recognised in the analysis, it can be an advantage to explore problems from a variety of viewpoints. Nevertheless, qualitative research cannot investigate causality and focuses on the content and value of information. Another potential disadvantage is that extensive and high level interviewing and questioning skills are required by a qualitative researcher in order to obtain consistent and reliable data from the respondents.

Since health care provision can be extremely complex a randomised controlled trial may not be able to define the parts of the whole package of care that contribute to the health improvements derived. As an example, implementing a dedicated stroke unit is an extremely complex intervention compared to using a new drug. The randomised controlled trial is ideally suited to assess the drug effectiveness using a comparison with a placebo. However, the stroke unit intervention is made up of a vast range of separate factors, some of which may contribute more than others to efficacy. Thus, there is great value in exploring complex interventions using qualitative methods to obtain a greater understanding of the content, process and benefits. This is only one example of what qualitative methods can offer the researcher, and also an example of where qualitative and quantitative methods can be used together (termed mixed methodology). There are many questions that are better answered using qualitative methods, particularly in areas where there is little knowledge and a greater understanding of the problem is needed.

There are a variety of approaches to qualitative research and these include; phenomenology, grounded theory, discourse analysis, ethnography and narrative research.

6.4.1 Phenomenology

Phenomenology is an approach that aims to explore the ways in which people conceive of and interpret the world. In this view, reality is relative and subjective (Stokes 2003). Phenomenology informs and helps the understanding of a particular phenomenon from a particular view point. An example is an investigation of the ways in which patients report their satisfaction with health care (the phenomenon). The researcher used in-depth interviews to explore the process of reflection that patients went through when asked to appraise their satisfaction with received health care (Edwards, Staniszweska & Crichton 2004). The interviews provided descriptions of a range of experiences from different patients, from which an essence of the phenomenon and a generalised statement about it could be derived. A critical aspect of phenomenology is the need for the researcher to suspend their own personal views or preconceived ideas about the phenomenon (known as bracketing), and seek to understand it through the views of the participants (Cresswell 1998). The aim of this type of inquiry is to show that although the phenomenon is experienced uniquely by each person, there exists an underlying unifying meaning of the experience that is essential and invariant for all people.

6.4.2 Grounded theory

Grounded theory is the systematic inquiry into a problem aiming to develop an overall theory based on personal experiences. The emergence of new data can alter or destroy the theory, so extensive data collection is required. As the theory emerges the researcher must constantly ensure it fits new data. An example is the exploration of the barriers to evidence-based nursing in order to develop a model of what barriers exist and how they relate to each other (Hannes et al. 2007). Hannes et al. used focus groups to collect data from nurses and reduced down the responses to five main themes that helped to formulate, what they called a ‘problem tree’, describing the interrelating issues.

6.4.3 Discourse analysis

Discourse analysis is a research approach that focuses on how talk and text can indicate how the world is understood. Studying conversations or written communications within a particular area can aid the understanding of people’s beliefs, views and attitudes towards something. An example is the analysis of conversations between pharmacists and older patients during consultations for medication review (Salter et al. 2007). The researchers analysed in detail the transcribed conversations to identify how advice was offered and how patients received it, to establish the value of such consultations.

6.4.4 Ethnography

The ethnographic researcher will observe and collect data on a group of people within their usual setting over a prolonged period of time. Ethnography is a form of inquiry that relies particularly on participant observation, focusing on the meanings of individual’s actions in a particular context. The context is important to enable a true understanding of events. For example, studying the decision-making process prior to withholding artificial administration of food and fluids involved two researchers becoming part of the health care teams at two nursing homes for seven and fourteen months (The et al. 2002). They made comprehensive notes on their observations and informal conversations; recorded formal interviews and meetings; studied medical records of the patients; and kept a diary of their own behaviour and attitudes. The latter process is vital in qualitative research and allows the researcher’s own preconceptions and experiences, as well as the effect of their presence, to be taken into account in the interpretation and analysis of events, and is known as reflexivity.

6.4.5 Narrative research

Narrative research is an approach which relies on the stories that people tell. Narratives are structured by the individual telling the story and will be organised in the way they see fit. How someone tells a story reflects how they have chosen to organise their thoughts and could be seen as the basis for how they acted. The order of the narrative will reflect the meaning that the storyteller wants to get across to the researcher. In a study to explore the patients’ experience of living with back pain, participants were asked to tell their own back pain story from when they first encountered such pain up to the current day (Corbett, Foster & Ong 2007). These narratives were analysed to produce themes which represented commonalities between the stories, and used to try to better understand the patients’ experience of this condition.

6.5 How to choose the right research design

Matching the research approach and specific design to your defined research question is the next step in the research process. The preceding sections have provided a broad overview of the available methods you could use and you now need to consider which will provide the answers you are looking for. This is easier when your research question is clear and you may need to think through your question again at this point.

Think about the following:

What type of evidence are you trying to produce? Are you trying to ‘prove’ a point (quantitative) or understand something better (qualitative)?

What type of evidence are you trying to produce? Are you trying to ‘prove’ a point (quantitative) or understand something better (qualitative)?Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree