Chemotherapy

This chapter provides basic concepts and principles related to chemotherapy and the primary mechanisms of action in the treatment goals of oncology patients. In addition, standards related to safe handling, administration, patient/family education, and specific specialty populations are reviewed.

BIOLOGIC AND PHARMACOLOGICAL BASES FOR CANCER CHEMOTHERAPY

• Adjuvant therapy is given after a primary treatment (surgery, radiation); the goal is to reduce chance of recurrence by targeting remaining disease after primary treatment.

• Neoadjuvant therapy is given before another treatment with the goal of shrinking tumor before removal or decrease the likelihood of micrometastasis.

• Chemoprevention is the use of selected agents to prevent cancer from occurring in identified high-risk individuals (e.g., tamoxifen).

Myeloablation is the obliteration of bone marrow as preparation for stem cell or bone marrow transplantation (Kelleher, Polovich, & White, 2005). Chemotherapy is also used as a primary treatment to treat a tumor usually seen with minimal disease. It is very important that patient and family members are informed of treatment goals before the initiation of therapy to allow them to set realistic goals in their personal lives. The information needs to be repeated throughout the course of planned treatments.

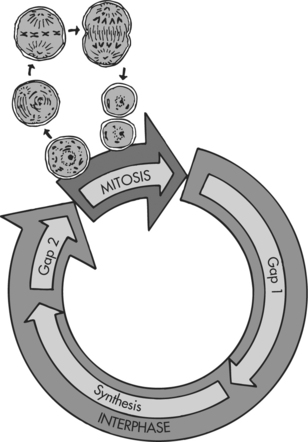

Chemotherapy is usually given as combination therapy using two or more agents together. The combinations of different agents affect the cell at different points in the cell cycle, allowing for maximum cell kill while minimizing toxicities. Principles for selection of chemotherapeutic agents for combination therapy include (1) choose drugs with single-agent activity, (2) avoid drugs with overlapping dose-limiting toxicities, (3) administer drugs at optimal dose and schedule as determined by clinical trials, (4) give chemotherapy at regular intervals, and (5) minimize the time between cycles (Tortorice, 2000). Combination therapy may also increase the range of drug activity resistance of tumor cell to single agents. In addition, combination chemotherapy may prevent or slow the development of resistance by the cancer cells and have a synergistic effect in combination with other agents (Brescia, 2003).

Tumor cells exposed to chemotherapy sometimes develop mechanisms to protect themselves against the drugs effect. Resistance is the term used to describe the process. Resistance may result from alteration in chemotherapeutic agent metabolism, alteration in cytotoxic targets, biochemical cofactor presence or absence, ability of cell to repair deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) lesions, or decreased intracellular drug concentration. The most significant explanation of drug resistance is the P-glycoprotein efflux pump associated with overexpression of the MDR-1 gene (multidrug resistance) (Tortorice, 2000). Drug resistance may have many factors that affect response to therapy. Resistance may be inherent or acquired, single agent or multidrug, temporary or permanent. Prevention of drug resistance is another justification for combination chemotherapy (See the box below).

Biochemical Mechanisms Involved in Drug Resistance

• Impaired transport of the chemotherapeutic drug across the cell membrane

• Decreased intracellular activation of the chemotherapeutic drug

• Altered or increased amounts of the intracellular target for the chemotherapeutic drug

• Increased intracellular detoxification of the chemotherapeutic drug

• Increased efficiency of DNA repair of cellular damage caused by the chemotherapeutic drug

From Miaskowski, C. & Viele, C. (1999). Cancer chemotherapy. In C. Miaskowski & P. Buchsel (Eds): Oncology nursing: Assessment and clinical care. Mosby: St. Louis, MO.

CHEMOTHERAPY CLASSIFICATIONS

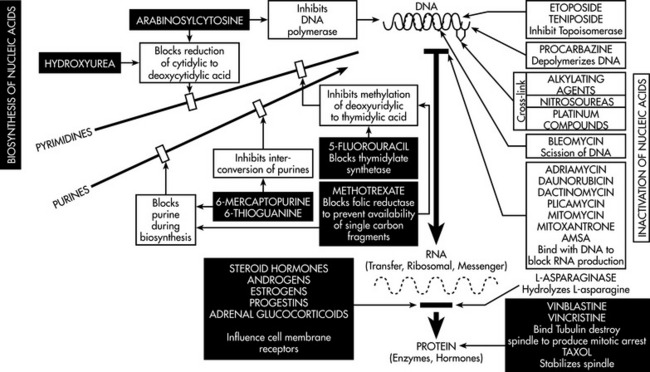

Chemotherapeutic agents are classified by mechanism of action and specificity. The major classifications are listed in the box below. See the figure on page 185 for a diagram of chemotherapeutic agent mechanism of actions. Each classification contains agents that have similar characteristics and side effect profiles. Although the agents are similar, each agent must be addressed on an individual basis or in combination with finalization of a treatment plan.

Major Classification of Chemotherapeutic Drugs

From Miaskowski, C. & Viele, C. (1999). Cancer chemotherapy. In C. Miaskowski & P. Buchsel (Eds): Oncology nursing: Assessment and clinical care. Mosby: St. Louis, MO.

Nitrosoureas

Nitrosoureas are cell cycle–nonspecific agents that have the same mechanism of action and toxicities as alkylating agents with the inclusion of gonadal toxicities. They also have the ability to cross the blood-brain barrier. Nitrosoureas have a high lipid solubility that enables them free passage across membranes; therefore, they rapidly penetrate the blood-brain barrier, whereas most other agents are unable to do so (Calvo & Takimoto, 2005). Blood-brain barrier penetration allows nitrosoureas to be prominently used in the treatment of brain tumor and other central nervous system diseases. Common nitrosourea agents include carmustine, lomustine, and streptozocin.

Antitumor Antibiotics

Antitumor antibiotics are cell cycle–nonspecific agents with variable sites of effect dependent on the agent used. Antitumor antibiotics are also referred to as natural products because they occur naturally or are synthesized from microorganisms and have both antimicrobial and cytotoxic activity. Antitumor antibiotics have two primary mechanisms of cell kill: free radical formation and the inhibition of topoisomerase II enzyme that results in DNA disruption and eventually cell death. Antitumor antibiotics are also known as anthracyclines. Cardiac tissues, because of a complex drug-iron complex, are especially vulnerable to anthracyclines (Tortorice, 2000). Common toxicities include myelosuppression and GI, cutaneous, and primary organ toxicities (cardiac, pulmonary). Routes of administration include intravenous, intra-arterial, or intravesical (bladder instillation). Common antitumor antibiotics include bleomycin, dactinomycin, daunorubicin, daunorubicin citrate liposomal, doxorubicin, doxorubicin liposomal, epirubicin, idarubicin, mitomycin, mitoxantrone, and valrubicin.

Microtubular Stabilizing Agents

A number of agents are in clinical development that target microtubules. Intact microtubules are needed for the formation of mitotic spindles in the process of cell division. This new class of chemotherapy drugs is called epothilones (Goodin, Kane, & Rubin, 2004; Petrylak & Kelly, 2004). The agents have been isolated from the mycobacterium, Sporangium cellulosum. The drugs work in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle to initiate apoptosis. Epothilones provide an advantage over taxanes by binding to a different site. Therefore, epothilones provide activity in cancers that have developed taxane resistance.

Epothilones have shown activity in several cancers, including breast, lymphoma, renal, prostate, and ovarian. Side effects are similar to those of taxanes. Hypersensitivity reactions have been reported in cremophor-based epothilone agents. Other side effects to monitor for are neutropenia, peripheral neuropathy, fatigue, arthralgia, myalgia, nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, and stomatitis. Several of the current agents in development are ixabepilone and patupilone (Goodin, Kane, & Rubin, 2004; Petrylak & Kelly, 2004).

PATIENT AND FAMILY PREPARATION FOR CHEMOTHERAPY ADMINISTRATION

Patient and Family Assessment

The nurse administrating the chemotherapy should conduct a pretreatment assessment of the patient according to the guidelines listed in the box on page 187. Along with these guidelines, the nurse should keep in mind that patients will come with a lifetime of influences that affect the response to all of the changes involved with a diagnosis of cancer and required treatment. Past experiences affect their current physical presentation at diagnosis and how they will perceive current interactions with the health care team. Preconceived ideas of cancer, cultural and ethnic background, adult learning style, educational background, socioeconomic status, past coping mechanisms, and numerous other influences will affect the needed preparation for chemotherapy. Inclusion of family, significant others, or existing support systems is critical in preparation for chemotherapy initiation.

Patient and Family Education

Formulation of a teaching plan should incorporate knowledge of the patient’s and family’s primary language and level of understanding, ability to read, readiness to learn, anxiety levels, and any other potential barriers to learning (Miaskowski, 1997; Powell, 1996). The nurse should review the topics outlined in the boxes on p. 187 and provide written material to reinforce all verbal instructions.

SAFE HANDLING

One of the most prevailing issues for staff is the inherent potential for harm in the delivery of care to cancer patients. Chemotherapy agents are hazardous drugs. The term “hazardous drugs” leads one to proceed with caution in the administration of these agents. Hazardous drug handling guidelines have been available for 20 years. According to the American Society of Health System Pharmacists (ASHP), any drug that requires special handling is referred to as a hazardous drug (ASHP, 2005). Recommendations for practice have been established by the Oncology Nursing Society (ONS), the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) for safe handling of chemotherapy. The four major goals for safe handling of chemotherapy are listed in the table below.

| Drug Class | Mechanism of Action | Drug Name |

|---|---|---|

| Alkylating agents | Cell cycle nonspecific | |

| Binds with DNA and protein molecules | ||

| Antitumor antibiotic | Cell cycle nonspecific | |

| Antimetabolites | ||

| Nitrosoureas | ||

| Epothilones Ixabepilone Patupilone | ||

| Miscellaneous | Cell cycle non-specific |

Guidelines for the Pretreatment Assessment of the Chemotherapy Patient

OBTAIN A COMPLETE PATIENT AND FAMILY HISTORY

OBTAIN A PSYCHOSOCIAL ASSESSMENT OF THE PATIENT AND FAMILY MEMBERS

Reactions to the diagnosis of cancer

From Miaskowski C & Buchsel P. (1999). Oncology nursing assessment and clinical care. St. Louis: Mosby.

Patient Education Regarding Chemotherapy

1. Review the treatment plan and protocol.

2. Review the purpose or the goals (i.e., cure palliation) of the chemotherapeutic treatment.

3. Review the potential side effects of chemotherapy and self-care activities to prevent or treat the side effects.

4. Review the schedule and rationale for diagnostic tests.

5. Provide the patient and family members with information on when and how to contact the nurse or the physician.

Data from Oncology Nursing Society. (2005). Chemotherapy and biotherapy guidelines and recommendations for practice (2nd ed.). ONS: Pittsburgh, PA.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree