Chapter 36 Challenges in pregnancy

Learning outcomes for this chapter are:

1. To describe the effects that complications in pregnancy have on the woman, her family, the pregnancy and the unborn baby

2. To discuss the pathophysiology of, diagnosis of, evidence for treatment of, and expected outcomes associated with, common complications in childbearing

3. To identify strategies to support women as they are challenged by and deal with the physical and psychological complications of ‘high-risk’ birthing.

The midwife, working in partnership with the woman, manages many of these challenges in a primary setting However, when complications fall outside the scope of midwifery practice, midwives, still working in partnership with the woman, consult colleagues in a timely manner and work collaboratively with them to jointly manage secondary and tertiary levels of care.

INTRODUCTION

This chapter focuses on an exploration of the most common complications arising in pregnancy—some pre-exist pregnancy, others are exacerbated by pregnancy, and a few occur de novo. All pose challenges for the parents and their unborn baby, and the clinicians’ role is to ensure best practice and outcomes. This chapter builds on the philosophy, principles and actions described in Chapter 22, because if a midwife is to understand the ‘abnormal’ she must first know the ‘normal’. ‘High-risk’ maternity care is not just about assessments, investigations, diagnoses, conditions and medical treatment, but is also about women from different ethnic, socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds who, while pregnant, must still face common life stressors while they deal with pregnancy complications and deal with their anxieties and fears about their own and their baby’s health and about the wellbeing of their family. Thus midwifery care is also about supporting women as they make the sometimes uncertain journey towards birth, one sometimes complicated by obstacles that result in actual or potentially life-threatening situations. The complications discussed in this chapter include the specifics of hyperemesis gravidarum, bleeding, preterm labour and birth, medical conditions, hypertension and multiple pregnancy, as well as the social and psychological variables that affect these conditions and their outcomes.

VOMITING IN PREGNANCY

Hyperemesis gravidarum

Hyperemesis gravidarum (HEG) is a debilitating illness, affecting one in 200 pregnant women (Quinlan & Hill 2003), beginning at about the fourth week of pregnancy and usually improving by the 20th week, although some women continue to have recurring bouts throughout the whole pregnancy. It is characterised by: persistent and intractable vomiting leading to fluid and electrolyte depletion and imbalance; marked ketonuria; and nutritional deficiency and rapid weight loss. Severe HEG requires hospital admission in 0.3%–2% of pregnancies. There is scant evidence to suggest that any socioeconomic class, racial or ethnic groups are at increased risk of HEG. One study has noted an increased risk among Pacific Islander (Polynesian) women (Browning et al 1991). Most cases of HEG occur in nulliparous women, although a 2005 study showed a high risk of recurrence in second pregnancies, which was reduced by a change in paternity. Further, a long interval between births slightly increased the risk of hyperemesis in the second pregnancy (Trogstad et al 2005). Conversely, pregnant women older than 35 years of age and smokers seem to be less at risk (Abell & Riely 1992).

The pathophysiology of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy and HEG is poorly understood but is likely to be multifactorial (Hyperemesis Education and Research Foundation 2004; Quinlan & Hill 2003). Related physiological factors are:

• Elevated pregnancy hormones (e.g. human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG), oestrogen and progesterone)—hCG levels are higher than usual in some conditions associated with hyperemesis, nausea and vomiting in pregnancy (molar pregnancy and multiple pregnancy). hCG has been associated with HEG because its peak concentration in pregnancy coincides with the peak of nausea and vomiting, especially in cases of hydatidiform molar pregnancies.

• Gastric dysrhythmias—displacement of the gastrointestinal tract; delayed gastric emptying; lower oesophageal sphincter pressure and increased levels of gastric hydrochloric acid; hyperacuity of the olfactory system; and altered hormone levels. Many pregnant women report that the smell of cooking food, particularly meats, trigger nausea. Striking similarities between HEG and motion sickness suggest that subclinical vestibular disorders may account for some cases of HEG.

• Autonomic nervous system changes —in blood volume, temperature, heart rate and vascular resistance.

• Nutritional deficits (e.g. trace elements—zinc, copper and vitamin B6).

• Liver enzyme abnormalities. Elevated serum bilirubin, aminotransferase and alkaline phosphatase may be secondary to HEG rather than a cause of it.

• A slow adaptation of the liver to the increased levels of hormones in pregnancy may result in abnormal levels of serum lipids and lipoproteins.

• Chronic infection with Helicobacter pylori (Hayakawa et al 2000).

• Psychogenic factors, for example ambivalence or rejection of the pregnancy, and depression.

Women are at higher risk of having HEG if they have a multiple pregnancy, are daughters and sisters of women who also had the condition, are carrying a female fetus, and have a history of HEG in a previous pregnancy. Other risk factors include a history of motion sickness or migraines.

The 5% of women who develop HEG are often offered little sympathy, let alone practical or effective solutions to a debilitating problem that has a major impact on their self-esteem and daily living activities. There have been a number of explanations for this neglect. In one study, Fairweather (1968) administered the Cornell Medical Index to 44 pregnant women with HEG and 49 pregnant women without the condition. Inexplicably, the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) was given only to the HEG group, making the findings meaningless. The study says a great deal about the researchers’ beliefs about women in general and the mental-health state of women with HEG in particular. The authors concluded that women with hyperemesis had hysteria, were overly dependent on their mothers and had infantile personalities. Forty years later, discussion with women with HEG reveals that some clinicians’ behaviour shows they have not moved beyond this way of thinking.

Collaborative support for a woman with hyperemesis

It is important to rule out other pregnancy- and non-pregnancy-related causes such as pyelonephritis, drug toxicity, and biliary tract and liver disease. Pregnancy-related differential diagnoses include multiple pregnancy or a hydatidiform mole. Traditionally the treatment of hyperemesis has been supportive, with reassurance, dietary modifications and lifestyle changes, but there is no evidence of the benefits of any of these interventions (Jewell & Young 2002).

Medications for HEG

A number of published reviews, including a 2002 Cochrane Review (Jewell & Young 2002) have examined

Clinical point

Education for women with severe nausea and vomiting in pregnancy

• Eat a diet high in complex carbohydrates (such as bread, rice, potatoes) and protein, and low in fat.

• Eat five to six small meals a day, including a late-evening snack. Low blood sugar can cause nausea and shakiness. Some women find sucking on hard sweets helpful.

• Try eating a small snack before getting up.

• Eat many small meals each day but avoid lying down immediately after eating.

• Get plenty of rest. Being overly tired can set off nausea.

• Consider taking ginger supplements.

• Avoid noxious odours that trigger vomiting, cigarette smoke and tastes that trigger nausea, such as coffee.

• Consider acupuncture or acupressure to assist in relieving nausea.

a range of pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical treatments for nausea and vomiting in pregnancy (Mazzotta & Magee 2000; Meltzer 2000; Moran & Taylor 2002; Nelson-Piercy et al 2001). In summary, they show that there is no firm evidence that the administration of pyridoxine (vitamin B6) alone or with doxylamine has a clinically significant effect on severe vomiting. However, according to Jewell and Young (2002), it may be the most effective drug with the fewest side-effects.

Concern has been raised recently about a marginally increased risk of congenital malformations associated with using steroid therapy, which may resolve nausea and vomiting in pregnancy (Quinlan & Hill 2003). Since the thalidomide tragedy, anti-emetic therapy is generally reserved for those whose symptoms are so severe that they pose a threat to the safety of the mother and her unborn baby. However anti-emetics such as promethazine and metoclopramide are widely used. Therapy should be stopped two weeks before birth, as withdrawal symptoms in the infant can occur.

No randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have been published to support the effectiveness of metoclopramide as a treatment for nausea and vomiting in pregnancy (Mazzotta & Magee 2000). Extrapyramidal reactions sometimes occur, particularly in young women. Similarly, no RCTs have investigated the effectiveness of domperidone in treating HEG (Mazzotta & Magee 2000). Serotonin antagonists such as ondansetron (Zofran®) decrease stimulation to the vomiting centre in the brain, but as yet there is no evidence that this medication makes a significant difference to outcomes (Mazzotta & Magee 2000).

Non-pharmaceutical treatments

In brief, ginger may reduce nausea and vomiting in pregnancy (Keating & Chez 2002; Mazzotta & Magee 2000; Vutyavanich et al 2001;). According to Meltzer (2000), ginger may have adverse effects on fetal brain development, and in therapeutic quantities could increase bleeding in early pregnancy.

Box 36.1 Support for women with hyperemesis

HER Foundation

The Hyperemesis Education and Research (HER) Foundation is dedicated to those suffering from HEG and those who have survived it. HER can be contacted at: www.hyperemesis.org.

(Source: adapted from Hyperemesis Education and Research Foundation 2005)

beneficial effects for nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. However, data from a large RCT was not included in the review, and this trial showed no benefit from acupressure (Jewell & Young 2002).

Case reports of the efficacy of hypnosis, hypnotherapy, and psychotherapy and behaviour modification on the treatment of hyperemesis have been published but none have reported significant benefits (Jewell & Young 2002; Mazzotta & Magee 2000). Herbal remedies such as red raspberry or wild yam have been used to treat hyperemesis, but again there is no evidence to support their efficacy or safety. Finally, there are no published trials regarding the efficacy of homeopathic remedies as a treatment for HEG.

Ongoing treatments

Left untreated, the woman with HEG may develop renal, neurological or hepatic damage. In severe cases, splenic avulsion, oesophageal rupture, peripheral neuropathy and preeclampsia as well as fetal intrauterine growth restriction and increased mortality can occur (Quinlan & Hill 2003). Termination of pregnancy may be the woman’s choice, especially if severe renal, neurological or hepatic involvement is apparent.

Summary

The following recommendations are based on limited or inconsistent scientific evidence:

• Taking multivitamins may decrease the severity of symptoms.

• Taking Vitamin B6 or Vitamin B6 plus doxylamine (an antihistamine) should be considered a first-line treatment.

• Ginger may be a non-pharmacological option.

• Antihistamine H1-receptor blockers, phenothiazines and benzamines are safe and possibly effective in treating refractory cases.

• Early treatment may prevent progression to severe HEG.

• Methylprednisolone is a treatment of last resort due to its potential risk to the fetus.

BLEEDING IN PREGNANCY

Any bleeding in early pregnancy—that is, the first or second trimester—is considered a threatened or an actual miscarriage (abortion) until proved otherwise. A miscarriage can be an intensely sad and frightening experience for everyone. A pregnancy that seemed normal suddenly ends, leaving the expectant parents devastated. About 20% of women with clinically diagnosed pregnancies will experience bleeding at some time in early pregnancy (Bryan 2003). Overall, up to 50% of all pregnancies end in miscarriage although many more losses occur before a woman realises she is pregnant (ACOG 2001). Of these, about 20% of recognised pregnancies end in miscarriage (Bryan 2003). Most miscarriages occur during the first trimester and are called ‘early miscarriages’. Those occurring between 13 and 20 weeks are ‘late miscarriages’.

Definition and classification

Threatened miscarriage (abortion)

Vaginal bleeding (spotting) before the 20th week of pregnancy and possibly accompanied by low back or abdominal pain are usually the first signs of a threatened miscarriage. The amount of bleeding and the presence of pain have little value in predicting the viability of the pregnancy (Bryan 2003). Women experiencing a threatened miscarriage have an approximately 85% chance that their pregnancy will progress to term. The bleeding is usually self-limiting, and is sometimes attributed to trophoblastic implantation within the endometrium rather than a miscarriage per se. On examination, the cervix remains closed, and the uterus is soft and non-tender and of appropriate size for gestational age.

Inevitable (imminent) miscarriage

When vaginal bleeding persists and is accompanied by dilation of the internal cervical os or rupture of the fetal membranes, a miscarriage is inevitable. Bleeding is usually more severe than with a threatened miscarriage and often associated with uterine contractions. It is not

Box 36.2 Miscarriage support

Miscarriage Support Auckland Inc. (www.miscarriagesupport.org.nz/index.html) is a team of volunteers who have all experienced the loss of a baby. Sharing their experience with others has assisted many women with the grieving progress and set them on the road to recovery.

usually possible to save the pregnancy. In early pregnancy ultrasound can usually detect pregnancies which are destined to miscarry inevitably, including those that are already non-viable (Sawyer et al 2007). Non-viable pregnancies are either a ‘missed miscarriage’ if an embryo or fetus is present but is dead, or an ‘anembryonic pregnancy’ if no embryo has developed within the gestation sac.

Silent or delayed miscarriage (missed abortion, blood mole, carneous mole or stony/fleshy mole)

woman’s story, physical examination, laboratory tests and ultrasonography. Blood and urine tests will show a drop in β-hCG levels. An ultrasound examination shows early evidence of an intrauterine pregnancy but only an empty pregnancy sac.

Management of early pregnancy loss

Early pregnancy assessment units

The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (2001) guidelines recommend that all maternity centres provide an early pregnancy assessment service with direct access for women, midwives and medical personnel. A dedicated early pregnancy assessment unit (EPAU) can streamline the management of women with early pregnancy bleeding or pain and thus improve the quality of care, in the presence of a supportive, multidisciplinary team.

Collaborative care

According to Bryan (2003), the choice of management options depends largely on the clinician’s and woman’s preferences. However, in a partially randomised study comparing surgical and medical treatments, 20% ofwomen expressed a strong preference for medical management (Hinshaw 1997). The main reasons given for their choice was that they wanted to avoid general anaesthesia and felt more in control of the procedure and outcomes.

Until the late 1980s, dilation and curettage (D&C) was the ‘gold standard’ for management of miscarriage because it was quickly performed and it was possible to remove any remaining retained products of conception (Ankum et al 2001). Histological examination of the removed tissues also allowed exclusion of trophoblastic disease. More recently, with the advent of technology such as transvaginal sonography (TVS) (Bryan 2003), clinicians have adopted a more conservative approach to management (Ankum et al 2001; Bryan 2003). A curettage is no longer considered mandatory but may be required if the woman is haemorrhaging, has an infection, or if an ultrasound shows that there is placental tissue remaining in the uterus. Conservative or expectant approaches usually involve making the diagnosis of an incomplete miscarriage with ultrasound followed by drugs such as prostaglandins, for example misoprostol, prostaglandin F2alpha, or other uterotonic drugs (ergometrine, oxytocin) or anti-hormone therapy to expel the tissue (Ankum 2001; Luise et al 2002). The progesterone antagonist mifepristone may also be effective in promoting expulsion of retained products of conception following miscarriage (Tang & Ho 2006).

• be offered the opportunity to attend for follow-up care, possibly with EPAU staff or their lead carer in the community

• have plans for follow-up clearly recorded in the discharge letter from the EPAU to the lead carer

• be informed that they can expect a grief reaction

• be informed that lactation may need to be suppressed

• be given the contact details of local support groups

• understand that it may take months to recover physically and emotionally from a miscarriage

• know that they will probably experience a menstrual period four to six weeks after the miscarriage.

Emotional recovery from early pregnancy loss

The comprehensive management of pregnancy loss is enhanced by psychological support and follow-up counselling (Boyce et al 2002). This could be provided by the woman’s GP or other support services, who can address medical as well as psychological issues. For some couples, a miscarriage causes both severe and protracted distress at a level not appreciated by all professionals involved.

The purpose of follow-up counselling, according to Boyce et al (2002), is to provide:

• open discussion about the loss, monitor progress and counsel the woman about future pregnancies

• an opportunity for the woman to talk about her loss and have her grief acknowledged

• information about the normal grief process

• facilitation of the grief process by enabling the woman to talk about her feelings of guilt and self-blame, particularly when there is no medical explanation for the loss

• an opportunity for the woman and her family to discuss their dissatisfaction, if there is any, with their care.

Often women want to know how long they must wait before attempting another pregnancy. The response to this question is that the couple should not attempt another pregnancy until the woman is physically and emotionally ready and the couple has completed tests aimed at determining the cause of the miscarriage. Clinicians often advise the couple to wait until the woman has had one normal menstrual cycle, but it may take considerably longer before she is ready to attempt another pregnancy, especially if there has been a molar pregnancy. All women who have experienced miscarriage worry that they will miscarry again but the great majority will go on to have a subsequent successful pregnancy.

Recurrent pregnancy loss (habitual abortion)

While miscarriage is usually a one-time occurrence, about 1%–2% of couples have two, three or more consecutive miscarriages (Hogge 2003). If three consecutive pregnancies end in miscarriage, the couple requires referral to an obstetrician and probably a fertility specialist in an effort to determine the cause of the recurrent pregnancy loss. Possible causes are: chromosomal or other genetic abnormality; progesterone deficiency; infection; uterine abnormality; cervical ‘incompetence’; or systemic disease. Any miscarriage is distressing for the parents but recurrent miscarriages are devastating, especially if it is not possible to identify a cause and therefore a ‘cure’. Potential parents need to know that despite the battery of tests usually ordered during investigation of recurrent miscarriage; only 50% of couples will be given an answer for their inability to carry a live baby beyond two trimesters (ACOG 2001).

Implantation bleeding

Many healthcare professionals still believe that as the trophoblast implants into the endometrial layer of the uterus, bleeding can sometimes occur and escape from the uterine cavity into the vagina—hence the term implantation bleeding (Harville et al 2003). However, these authors found no evidence that implantation causes vaginal bleeding. In so-called implantation vaginal bleeding the loss is light and occurs a few days before menstruation would have been due. The bleeding is probably a threatened miscarriage.

Causes of miscarriage

The causes of miscarriage are not thoroughly understood and clinicians are frequently unable to give grieving parents a precise response to questions about why the miscarriage occurred. Up to 70% of first-trimester miscarriages are caused by fetal chromosomal abnormalities (Hogge 2003). These become more common with increased maternal age. There is good evidence that autoimmune diseases play a significant role in miscarriage. Autoantibodies associated with repeated miscarriage include anticardiolipin antibodies, which are associated with thromboembolic disorders. Studies suggest that this and related antiphospholipid antibodies cause between 3% and 15% of repeat miscarriages (ACOG 2001). In addition, a Factor V Leiden mutation, which affects blood clotting, may also play a role in repeat miscarriages (ACOG 2001).

Acute and chronic infectious diseases are well documented as causative factors in miscarriage. Bacterial vaginosis is the most common genital infection among women of reproductive age. The US-based Centers for Disease Control (CDC) estimates that as many as 16% of pregnant women have bacterial vaginosis (CDC 2004). Although having a new sex partner or multiple partners increases the chances of infection, the exact role that sexual activity plays in the infection is unclear. A recent study found that women with bacterial vaginosis were nine times more likely to have a miscarriage than uninfected women (Leitich et al 2003). Younger women of childbearing age are increasingly being infected with Chlamydia trachomatis but as the research box below shows, the precise relationship between genital infection and early and late miscarriage is still unclear. Numerous other microbial organisms blamed for miscarriage include cytomegalovirus (CMV), herpes simplex virus (HSV), rubella, parvovirus, Treponema pallidum and HIV.

Research findings

Association between bacterial vaginosis or chlamydial infection and miscarriage before 16 weeks gestation

The objective of one UK prospective community-based cohurt study (Oakeshott et al 2002) was to assess whether bacterial vaginosis or chlamydial infection is associated with early miscarriage (before 16 weeks). Of the 1201 women in the study, 14.5% had bacterial vaginosis. The infection was more common in participants who were: under 25, of Afro-Caribbean or black African ethnicity, from social classes 3–5, single, and had previously used oral contraception or none, and smoked during pregnancy; and those with a history of termination of pregnancy and who had a concurrent chlamydial infection. Compared with women who were negative for bacterial vaginosis, women who were positive had a relative risk of miscarriage before 16 weeks gestation of 1.2 (0.7–1.9). Only 29 women had a chlamydial infection, one of whom miscarried.

In summary

Many of the above factors are summarised in Box 36.4. However, in many cases there is no obvious cause of early reproductive losses. Pregnancies that proceed following a threatened miscarriage have an increased risk of complications and poor outcome compared with pregnancies where there is no bleeding (Bryan 2003). Miscarriage can sometimes cause profuse haemorrhage and infection, and it remains an important cause of morbidity, and even mortality. Complications from late miscarriage (after 13 weeks), in particular, can be serious if not treated in a timely and appropriate fashion, and are a common cause of maternal mortality in both high-income and low-income countries (Lewis 2007).

Molar pregnancy (gestational trophoblastic disease)

Clinical point

According to Weinberg (2001), approximately 4% of women who have a miscarriage will have a transplacental haemorrhage of >0.2 mL of fetal red blood cells. Since the late 1960s, anti-D immunoglobulin has been used successfully for Rhesus (Rh) prophylaxis. Non-sensitised Rh-negative women should be offered anti-D immunoglobulin in the following situations: ectopic pregnancy; all threatened or diagnosed miscarriages over 12 weeks; all miscarriages; and when the uterus has been surgically evacuated.

Sensitisation can occur after a transplacental haemorrhage of <0.1 mL, and so there is a potential for sensitisation in pregnancies of less than 12 weeks gestation, although research has yet to confirm this suspicion. Currently, the routine administration of anti-D immunoglobulin is not recommended in threatened miscarriages below 12 weeks gestation or if the fetus is viable. However, if the bleeding is heavy or associated with abdominal pain, Rhesus D sensitisation is more likely to occur. Weinberg’s UK study (2001) shows that many women who present to emergency departments with a threatened miscarriage such that there is an increased risk of Rhesus D isoimmunisation were not offered anti-D immunoglobulin. Discharge documentation should always clearly state whether or not anti-D immunoglobulin was offered, given, and by whom.

be related to poor nutrition, particularly a low intake of carotene (vitamin A precursor).

Complete and partial molar pregnancies (hydatidiform moles)

Hydatidiform mole can be subdivided into complete and partial moles based on genetic and histopathological features. Complete moles are diploid and androgenetic in origin, with no evidence of fetal tissue. Complete moles arise from the fertilisation of an ‘empty egg’—one that has lost its maternal genetic material. There is no embryo and no normal placental tissue. However, the placenta continues to grow and produces β-hCG, so the woman thinks and feels that she is pregnant. A complete mole demonstrates a characteristic vesicular pattern (resembling a bunch of grapes).

Medical diagnosis

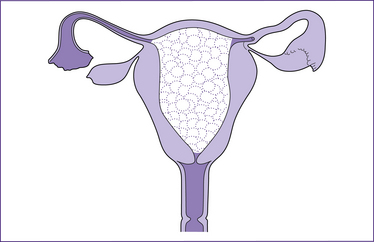

The widespread use of ultrasound has led to earlier diagnosis of pregnancy and has changed the pattern of molar pregnancy. The ‘gold standard’ of diagnosis remains the characteristic vesicular appearance of the placenta on ultrasound scan, typically a ‘cluster of grapes’ or a ‘snowstorm’ appearance (see Fig 36.1). Initially, levels of β-hCG—although not diagnostic—are often higher than normal with a complete mole but lower than normal with a partial mole.

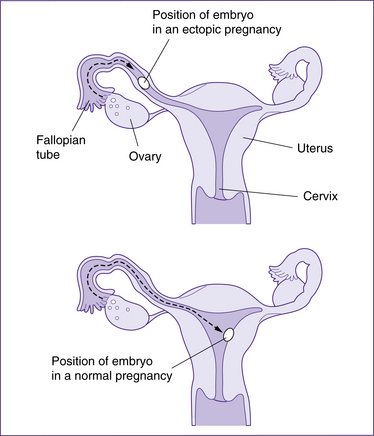

Ectopic pregnancy

An ectopic pregnancy occurs if a fertilised ovum implants at a site other than the endometrial lining of the uterus, most commonly in a fallopian tube, although ovarian, cervical and abdominal pregnancies are also possible. The incidence of ectopic pregnancy is estimated to be 1 in 200–500 pregnancies but is increasing (Tay et al 2000).

The diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy can now be made by non-invasive methods due to sensitive pregnancy tests (in urine and serum) and high-resolution trans-vaginal ultrasound (TVS). Improvements and greater efficiency in diagnosis have resulted in a range of both conservative and radical treatment options. Nevertheless, ectopic pregnancies are still a major cause of maternal morbidity and mortality in the first trimester. In the most recent Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) report Maternal Deaths in Australia (Sullivan et al 2008), one woman who was eight weeks pregnant died following a ruptured ectopic pregnancy. Most deaths result from delayed diagnosis, and inappropriate investigation and treatment.

Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy

A 1997 meta-analysis (Ankum et al 2001) showed that an earlier ectopic pregnancy, previous tubal surgery, documented tubal pathology, and in utero diethylstilbestrol exposure were the factors most frequently associated with the occurrence of ectopic pregnancy. Following assisted reproductive techniques such as in vitro fertilisation (IVF) or gamete intrafallopian transfer (GIFT), the incidence is as high as 1% (Ludwig et al 1999). Previous

genital infections (pelvic inflammatory disease [PID], chlamydia and gonorrhoea) and infertility was associated with a mildly increased risk (Ankum et al 1997).

Ectopic pregnancy is more common in women with a history of:

These last two risks only refer to the tiny proportion of women who become pregnant while using IUCDs or when taking oral contraceptives—they do not refer to all women who have in the past used these methods and later became pregnant. Of note is that the ‘morning after pill’ is associated with a 10-fold increase in ectopic pregnancy, but again this risk refers only to the proportion of women who become pregnant in spite of taking the medication, rather than to women who in the past have used the drugs.

Clinical presentation

In the initial stages of an ectopic pregnancy, although the fertilised ovum embeds into the fallopian tube

Clinical point

Up to 9% of women with an ectopic pregnancy report no pain even if the fallopian tube is close to rupturing, and 36% lack adnexal tenderness (Tay et al 2000).

the uterus still undergoes the normal changes of early pregnancy, and so the woman experiences the normal symptoms of pregnancy. Women who present to hospital in severe shock usually report warning signs that have been overlooked. While the woman typically has experienced nonspecific signs similar to those of a threatened miscarriage, she also complains of lower abdominal pain that precedes bleeding. Immediately prior to rupture, increasing abdominal pain is felt and rigidity and rebound tenderness are palpable. These signs, especially if they are accompanied by vaginal bleeding, which initially may be minimal but may quickly become torrential, together with signs of haemodynamic compromise/shock—hypotension, tachycardia, pallor, cold clammy skin, faintness and vomiting—should always alert the lead carer to the possibility of a ruptured ectopic pregnancy. In addition, shoulder-tip pain may be present, or pain may be referred to an iliac fossa. A mass may be felt to one side of the uterus. Any woman presenting with these signs requires immediate transfer to hospital and specialist consultation. If the clinical diagnosis is still unclear, an ultrasound scan will confirm or exclude the presence of an extrauterine gestational sac and, occasionally, a viable fetus.