5 Caring for the patient with a disorder of the liver, biliary tract and exocrine pancreas

ANATOMY AT A GLANCE

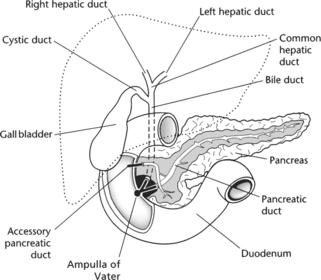

These closely associated structures are located in the upper abdominal cavity immediately below the diaphragm (Figure 5.1). The liver is a large organ weighing approximately 1.4 kg and is situated in the upper right portion of the abdomen. The gall bladder is much smaller (7–10 cm in length) and is located under the liver. Bile is passed from the liver to the gall bladder via the left and right hepatic ducts and subsequently into the duodenum via the bile duct. The pancreas lies across the upper abdomen being 12–15 cm long but only 2.5 cm thick. The head of the pancreas is located by the curve of the duodenum and the body and tail lie to the left of the head. Pancreatic secretions drain via the pancreatic duct into the duodenum. Normally, the pancreatic duct and bile duct enter the duodenum together as a common duct known as the ampulla of Vater.

PHYSIOLOGY YOU NEED TO KNOW

The liver has many vital functions and is metabolically extremely active. Key functions of the liver include:

The liver has many vital functions and is metabolically extremely active. Key functions of the liver include: The gall bladder. The liver secretes up to 1 L per day of strongly alkaline bile. It is stored and concentrated by a factor of up to 10 in the gall bladder before excretion into the small intestine, particularly to help digest the fatty portion of a meal.

The gall bladder. The liver secretes up to 1 L per day of strongly alkaline bile. It is stored and concentrated by a factor of up to 10 in the gall bladder before excretion into the small intestine, particularly to help digest the fatty portion of a meal. The exocrine pancreas constitutes 99% of this organ, the remaining 1% is the endocrine portion concerned with the secretion of hormones such as insulin and glucagon. The exocrine pancreas secretes pancreatic juice which contains a range of digestive enzymes needed in the small intestine. These include:

The exocrine pancreas constitutes 99% of this organ, the remaining 1% is the endocrine portion concerned with the secretion of hormones such as insulin and glucagon. The exocrine pancreas secretes pancreatic juice which contains a range of digestive enzymes needed in the small intestine. These include:CIRRHOSIS OF THE LIVER (P509)

PATHOLOGY: Key facts

Chronic and diffuse degeneration of the liver associated with the formation of scar tissue characterizes cirrhosis. The liver becomes congested, function deteriorates and portal hypertension ensues. Portal hypertension is associated with the development of ascites – the accumulation of large quantities of fluid in the abdomen due to disruption of the normal balance of pressures in the capillary bed impairing the return of fluid to the venous capillaries. The most likely cause is alcohol abuse although many alcoholics do not develop cirrhosis. Cirrhotic changes can also occur after chronic hepatitis, obstruction of bile flow (e.g. due to gallstones) or in response to autoimmune processes.

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT

Once the diagnosis is confirmed, alcohol intake must be eliminated, if that is the cause, to prevent further damage. There is no cure for cirrhosis although liver transplant may be offered if the person is willing to give up drinking. Medical management is usually symptomatic involving fluid restrictions and the cautious use of diuretics to reduce ascites. If the volume of ascites is interfering with respiration, paracentesis is performed using a sterile cannula to tap off the excess fluid from the peritoneal cavity.

PRIORITIES FOR NURSING CARE

Itching can be a major problem so apply anti-pruritic lotions and moisturisers, keep skin cool and change bedding daily. Assist with personal hygiene and keep nails short.

Itching can be a major problem so apply anti-pruritic lotions and moisturisers, keep skin cool and change bedding daily. Assist with personal hygiene and keep nails short. Assist with and encourage nutrition in accordance with dietician’s orders. Typically, this will involve a high-calorie (2500–3000 kcal/day) high-carbohydrate diet with vitamin supplements. Protein content may be limited or excluded completely depending upon the patient’s condition due to the toxic effects of accumulating nitrogenous waste substances which the liver is unable to metabolize.

Assist with and encourage nutrition in accordance with dietician’s orders. Typically, this will involve a high-calorie (2500–3000 kcal/day) high-carbohydrate diet with vitamin supplements. Protein content may be limited or excluded completely depending upon the patient’s condition due to the toxic effects of accumulating nitrogenous waste substances which the liver is unable to metabolize. The problem of alcohol intake will have to be discussed if this is thought to be the cause of the problem (p. 913). Box 5.1 reveals some key facts about alcohol intake, while Box 5.2 shows recommended daily intake limits. A useful tool which assesses whether a patient has an alcohol problem is shown in Box 5.3. If the patient answers yes to more than one of these questions, this indicates a likely problem. This can be used in primary care settings as well as in a hospital.

The problem of alcohol intake will have to be discussed if this is thought to be the cause of the problem (p. 913). Box 5.1 reveals some key facts about alcohol intake, while Box 5.2 shows recommended daily intake limits. A useful tool which assesses whether a patient has an alcohol problem is shown in Box 5.3. If the patient answers yes to more than one of these questions, this indicates a likely problem. This can be used in primary care settings as well as in a hospital. Patient education is crucial as there is no medical cure for cirrhosis, the patient has to learn to live with the disease and adapt their lifestyle accordingly to minimize its impact. Alcohol consumption is clearly contraindicated, however, some patients may be unable or unwilling to abstain leading to major health problems which may be compounded by related social problems such as family break up, unemployment and homelessness.

Patient education is crucial as there is no medical cure for cirrhosis, the patient has to learn to live with the disease and adapt their lifestyle accordingly to minimize its impact. Alcohol consumption is clearly contraindicated, however, some patients may be unable or unwilling to abstain leading to major health problems which may be compounded by related social problems such as family break up, unemployment and homelessness.Box 5.1 Alcohol consumption in the UK

In England in 2002, nearly two-fifths (37%) of men drank more than 4 units of alcohol in one day in the previous week; around one-fifth of women (22%) drank more than three units of alcohol in one day in the previous week.

In England in 2002, nearly two-fifths (37%) of men drank more than 4 units of alcohol in one day in the previous week; around one-fifth of women (22%) drank more than three units of alcohol in one day in the previous week. In England in 2002, 21% of men had drunk more than 8 units of alcohol in a day, at least once in the previous week, compared with 9% of women.

In England in 2002, 21% of men had drunk more than 8 units of alcohol in a day, at least once in the previous week, compared with 9% of women. In England in 2002, 27% of men and 17% of women aged 16 years and over were drinking more than 21 and 14 units a week, respectively. Drinking at these levels amongst men has remained stable at about 27% since 1992; that of women has risen from about 12%.

In England in 2002, 27% of men and 17% of women aged 16 years and over were drinking more than 21 and 14 units a week, respectively. Drinking at these levels amongst men has remained stable at about 27% since 1992; that of women has risen from about 12%. More than one-quarter (27%) of pupils aged 11–15 years drank in the previous week in 2003 in England, compared with one-fifth (20%) in 1988.

More than one-quarter (27%) of pupils aged 11–15 years drank in the previous week in 2003 in England, compared with one-fifth (20%) in 1988.From Department of Health (2004) Statistics on alcohol: England, 2004. Online. Available: www.dh.gov.uk/PublicationsAndStatistics/StatisticalWorkAreas

Box 5.2 Recommended daily alcohol intake limits

| Men: | 3–4 units |

| Women: | 2–3 units |

Department of Health (2006) Alcohol and Health. Online. Available: www.dh.gov.uk/PolicyAndGuidance/HealthAndSocialCareTopics/AlcoholMisuse [Accessed 08.04.2006]

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree