14 Caring for the patient undergoing endocrine therapy

Introduction

In Chapter 2, we discussed how some cancer cells grow in the presence of hormones (chemical messengers). Using this knowledge, endocrine or hormone therapy is a way of manipulating a patient’s hormones to reduce the growth of a cancer or prevent it from growing back.

Read Waugh and Grant (2010) (see References) or a similar textbook and make a list of the tissues/organs that are under the control of hormones. What is the role of these hormones and how might they influence cancer growth?

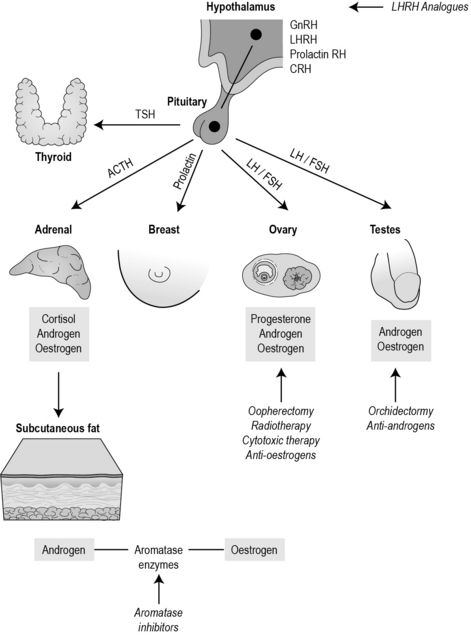

To give an example, the hypothamus produces luteinising hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH), which in turn stimulates the pituitary to release luteinising hormone, which stimulates the ovary to produce oestrogen which then triggers ovulation. Figure 14.1 identifies the hormone pathways particularly significant in cancer.

How endocrine treatments work

Cancers that arise from organs normally under hormonal control may be treated by endocrine therapy, namely breast, prostate, thyroid and endometrial cancers. Endocrine therapy either blocks hormones, increases hormones or inhibits the conversion of hormones. Generally, these treatments are not curative, but are useful neoadjuvantly, adjuvantly, palliatively and possibly as a preventative measure. Sometimes endocrine therapy is used as a sole treatment, where other treatments such as surgery are not recommended or a patient wishes to undergo a less invasive treatment. One of the reasons why endocrine therapy does not get rid of cancer completely is because as the cancer mutates, the cells look and behave differently to one another. Often some of the cells will be responsive to endocrine treatment, while others will not be. Sometimes a cancer will respond initially, but may become less responsive as the cancer mutates further. As stated in Chapter 2, at diagnosis a patient is tested to see if the cancer is sensitive to hormones. Sixty-five per cent of women with breast cancer will be oestrogen positive – these tend to be older women and they are more likely to have a better prognosis.

Remember that oestrogen is not only produced by the ovaries but also by the adipose tissues. After the menopause, a woman will continue to produce oestrogen because aromatase enzymes convert androgens into oestrogen. To stop this, the aromatase inhibitors (such as anastrozole) bind with the enzyme and stop the conversion. These drugs are now recommended by NICE (2006) for postmenopausal women with primary breast disease.

Table 14.1 summarises the main endocrine therapies

Table 14.1 Types of endocrine drugs

| Type of cancer | Type of endocrine therapy | Examples of agents |

|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer (pre- and postmenopausal) | Selective oestrogen receptor modulator (SERM) | Tamoxifen, droloxifene, idoxifene, raloxifene |

| Breast cancer (postmenopausal) | Aromatase inhibitors | Anastrozole, letrozole, exemestane |

| Breast cancer (postmenopausal) | Selective oestrogen receptor downregulator | Fulvestrant |

| Breast cancer (premenopausal) | LHRH analogues | Goserelin (Zoladex) |

| Endometrial cancer Prostate cancer (rarely) | Additive hormonal therapies | Megestrol acetate (Megace) and medroxyprogesterone (Provera) |

| Prostate cancer | LHRH analogues | Goserelin (Zoladex) |

| Prostate cancer | Anti-androgens | Steroidal: cyproterone acetate (Cyprostat) Non-steroidal: (flutamide TDS, nilutamide, bicalutamide/casodex) |

| Prostate cancer | Oestrogens | Stilboestrol |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree