16 Caring for patients at the end of life

Definition of end of life care

End of life care is often associated with the last days of life. This chapter takes a wider view and considers end of life care as the last ‘phase’ of life. The National Council of Palliative Care (NCPC) suggests ‘end of life care is simply acknowledged to be the provision of supportive and palliative care in response to the assessed needs of the patient and family during the last phase of life’ (NCPC 2006a:3).

The End of Life Care Strategy builds on this working definition from the NCPC by outlining six keys steps needed to be considered as part of the patient’s pathway (DH 2008:48):

1. Discussions as the end of life approaches.

2. Assessment, care planning and review.

3. Coordination of care for individual patients.

4. Delivery of high-quality services in different settings.

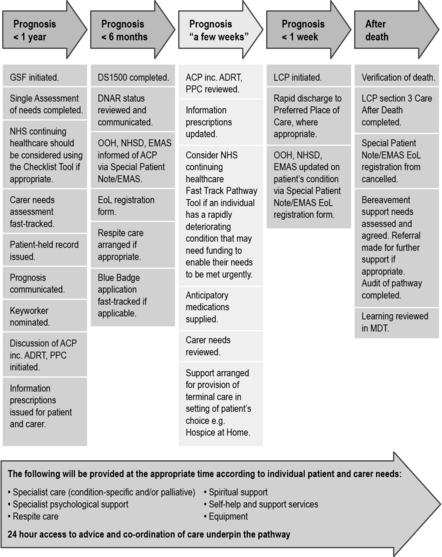

Some parts of the county have developed these six key steps into a structured patient pathway that spans the last year of life. By having a structured pathway, it is possible to start to consider planning care in advance with the patient and their family, with the aim to limit decisions being made in a time of crisis. Figure 16.1 is an example of one of these pathways used within a health community in Nottinghamshire.

Fig 16.1 Last Year of Life Pathway

(From Nottinghamshire End of Life Pathway for All Diagnoses (Next Stage Review Steering Group 2010). Reproduced with permission of NHS Nottingham City)

Consider the pathway in Figure 16.1 and make notes about what challenges might be faced by the patient, family and care team in each of the phases:

Now find out if your local health community has a specified pathway for last phase of life. It they do, how does it compare to the one in Figure 16.1?

The more definitive definition of end of life care used in the End of Life Care Strategy suggests it (DH 2008:47):

Best practice tools in end of life care

In England, there are several tools that have been developed that are considered to be ‘best practice’ tools in end of life care. These tools have been widely distributed through the National End of Life Care Programme Website (http://www.endoflifecareforadults.nhs.uk/, accessed November 2011) and are advocated by the End of Life Care Strategy (DH 2008). We now look at each of these tools and consider how they might be used across a range of practice placements.

Liverpool Care Pathway (LCP)

• The patient does not have pain.

• The patient is not agitated.

• The patient does not have respiratory tract secretions.

• The patent does not have nausea.

• The patient is not vomiting.

• The patient is not breathless.

• The patient does not have urinary problems.

• The patient does not have bowel problems.

• The patient does not have other symptoms. This can be a variety of things, for example an open wound needing dressing or a raised temperature.

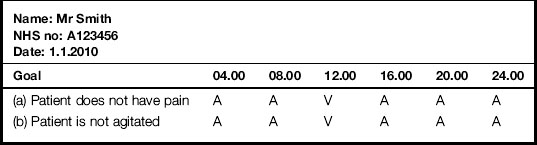

Looking at Mr Smith’s written record in Table 16.1, we see he was pain free and not agitated at 08.00 since it is indicated that these two goals had been achieved (A). However, at 12.00, we see there were signs of a variance (V) away from goals (a) patient does not have pain and (b) patient is not agitated. This means Mr Smith was in some way displaying signs of both pain and agitation.

Gold Standards Framework

1. The ‘surprise question: would you be surprised if this patient died within a week? If yes, then consider: would you be surprised if this patient died in a month? Six months? A year? The answer to this question can help the team consider if the patient is in the last phase of life. While we might be surprised if a patient we are caring for dies in a week, we might not be surprised if they die in 6 months’ time.

2. The patient with advanced disease makes a specific choice for comfort care only.

3. Clinical indicators of advanced disease are present: for example, increased agitation, falls, infections, pain and extreme fatigue. We look at these indictors later on in this chapter.

Preferred Priorities of Care

Understanding what a patient wants is very important when providing holistic care. The Preferred Priorities of Care (PPC) document was originally developed by Marie Curie Cancer Care to help focus attention on what is a priority for the patient; what it is they want and hope for. It is now kept up to date by the Preferred Priorities of Care Review Team (2011) and this latest version is available from the National End of Life Care Programme Website. Very often you will see families speaking out for a patient. They mean well and may say ‘He won’t want to go into hospital’ or ‘He wouldn’t want us upset by him dying in the house’. But how can we be sure this is what the patient wants? Instead, we need to be clear about what the patient wants, as well as understanding what is important to the family. Sometimes families can express their own fears and not the patient’s wishes. So what they may be saying to you is ‘I will feel so guilty if he goes into hospital’ or ‘How will we live in this house if he dies here’. The PPC contains various sections and supports patients in thinking though difficult issues and talking about the future.

Recognising dying and managing the last days of life

We have looked at some tools that can be used to help us care for the dying in their last phase of life. We now consider how we recognise dying in order to be able to use these tools. Recognising dying is not easy, even for the experienced professional (Furst & Doyle 2005). We must not take it for granted that other members of the team find this part of caring for a patient with advanced cancer simple and straightforward. Often the transition from curative cancer to last days of life care is complex. It can be a slow process or a sudden onset of new symptoms. Every patient must be assessed and treated individually. Patients tell us in many ways that they are dying. The challenge for the care team is to be aware of these signs to be able to recognise the dying.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree