Web Resource 9.1: Pre-Test Questions

Before starting this chapter, it is recommended that you visit the accompanying website and complete the pre-test questions. This will help you to identify any gaps in your knowledge and reinforce the elements that you already know.

Learning outcomes

By the end of the chapter the mentor should be able to:

- Analyse the rationale behind the development of career frameworks and policies

- Critically appraise the frameworks and policies for career progression

- Examine the various career pathways open to healthcare professionals

- Describe how mentorship skills can act as a springboard for career progression

Pre-Registration Career Pathways

The number of students admitted to universities and colleges to study medicine, dentistry, and nursing and midwifery are limited by financial restrictions. This is not the case for other healthcare professions and healthcare support workers, including allied health professionals, psychologists, healthcare scientists and pharmacists. Although there are exceptions, the demand for entry onto these courses are high due to the expectation that everyone who successfully passes the course will achieve a career in their chosen profession (most dental students qualify and become dentists). However, this is not always the case; many physiotherapists and medical graduates who have successfully passed the course have been unable to find work in their chosen profession. The reason for the mismatch in supply and demand was clearly defined by the fourth report of the House of Commons Health Committee on Workforce Planning 2006–2007:

Workforce planning should be simple: decide what workforce is needed in the future and recruit and train it. In reality the task is difficult and complex. The future workforce is difficult to predict: technology and social changes mean some skills become quickly redundant. … Even basic numbers are difficult to forecast: we may for example require fewer nurses and more doctors in 10 years – a problem which is exacerbated by the length of time it takes to train staff: 3 years for a nurse, 3 years for a physiotherapist, about 15 years for a surgeon. In addition, workforce planning has to be co-ordinated with financial and service plans.

The Skills Escalator aims at growing current healthcare staff (vertically and horizontally) and attracts a variety of entrants, such as the long-term unemployed, or socially excluded members of the population, into a career in healthcare, thereby filling the void in healthcare staff and complementing the current workforce.

The Skills Escalator claims to amalgamate pay modernisation, career frameworks and the Changing Workforce agenda. It promotes lifelong learning and continuous professional development, enhances equality, diversity and standards, and overall endeavours to improve recruitment and retention.

The Lifelong Learning Framework for the NHS, Working Together, Learning Together (Department of Health or DH 2001), underpins the Skills Escalator strategy by promoting healthcare workers’ skills and knowledge.

Under Agenda for Change (DH 2004a) the knowledge and skills framework demonstrates various levels of knowledge and skills that are required for specific roles. This system promotes a systematic approach to promoting staff via a gateway for career progression. It financially rewards lifelong learning and challenges staff to achieve their aspirations.

Entrants seeking to qualify as nurses, midwives or allied health professionals come from a diverse range of backgrounds and commence training from a variety of starting points. The traditional entry routes for registered health professionals are being complemented by offering a range of lower access routes on which entrants can climb up the career ladder. In theory, this wide access to healthcare training could enable a porter or cleaner to become a consultant.

In order to meet changing health needs, the role of many traditional health professionals is changing. These changes are all set within the context of regulation.

In medicine and nursing, new roles such as anaesthesia practitioners, physician assistants, nurse endoscopists and out-of-hours care practitioners are being developed, and GPs and other health professionals with a special interest are being trained in most areas of Scotland. In addition, the unregistered clinical workforce is being upskilled in a range of procedures.

Work is currently under way to develop an education and training framework for healthcare support workers and assistant practitioners who will deliver protocol-based clinical care under the direction and supervision of a registered practitioner. More specifically, education is currently being delivered to prepare maternity care assistants to support midwives, women and babies, and to promote breastfeeding and good parenting skills.

Pharmacists are being given additional training to help them manage common conditions such as asthma and epilepsy and undertake supplementary prescribing. Pharmacist assistants are able to perform a range of tasks once restricted to pharmacists.

A key development in the provision of dental treatment is the upgrading of the professions allied to dentistry (now known as dental care professionals or DCPs). These include dental therapists and dental hygienists whose role is now combined into the new role of oral health therapist. The oral therapist is able to treat both adults and children and undertake clinical procedures in primary care. This was prohibited previously. In addition, the role of dental nurses is being augmented, so that some simple clinical procedures can be delivered by this group of staff.

In addition, academic medicine is becoming more specialised as research is increasingly undertaken in multidisciplinary groups. The contribution that clinically trained scientists make to research in new therapies and drugs is increasing. We need to consider any changes to the role of doctors within the wider UK context and how the recommendations included in the Tooke Report (Tooke 2008) will impact on postgraduate medical education.

These developments require changes to the training provision at pre-registration level and upskilling of existing staff. It may also require the recognition of prior learning and a greater understanding of how this, and the learning required to address any skills gaps, align with the Scottish Credit Qualification Framework (SCQF). The SCQF is the national credit transfer system for all levels of qualifications in Scotland (Scottish Credit Qualification Framework Partnership 2007). England, Wales and Northern Ireland have a similar framework that integrates with the European credit transfer system.

Web Resources

Web Resources

9.2a: The Clinical Education Career Framework (NHS Education for Scotland)

9.2b: Useful Websites

These frameworks can be found on the accompanying website and at www.nes.scot.nhs.uk/media/5840/nmahp-careers-poster.pdf .

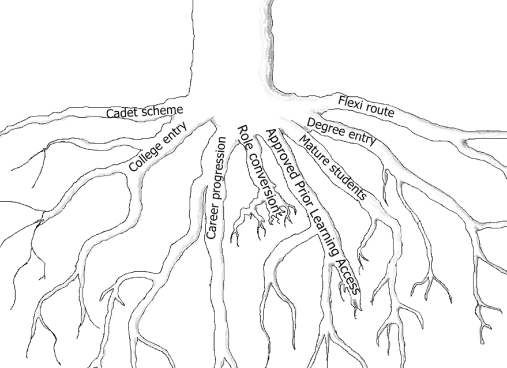

Career Entry Routes (Figure 9.1)

- Pre-registration programme

- Cadet schemes

- Career progression – porters, cleaners, GP receptionist’s progress to healthcare assistants

- Role conversion – healthcare assistants to nurses, midwives or allied health professionals

- Mature students with previous careers

- Those with limited formal education: the long-term unemployed and older people looking for a second chance

- Those with a wide range of transferable knowledge and skills (approved prior learning)

- Full- and part-time university access

The post-qualification careers of health professionals has traditionally followed fairly predictable paths: qualifying → junior post → senior post → management or education. This trajectory relied on the traditional structures and roles that were part of healthcare systems defined by inflexibility and predictability. Career development was not necessarily thought to be important or even an appropriate ambition. Often, career progression happened by accident or by individuals drifting into particular roles rather than by design and planning.

Web Resource 9.3: Case Study: Demonstrating a Career Pathway

Web Resource 9.3: Case Study: Demonstrating a Career Pathway

Visit the attached web page and view a case study that demonstrates one traditional career pathway.

There has been and continues to be considerable redesign in the provision of healthcare due to political changes, economic constraints, social and demographic changes, an ageing workforce, and the expansion and devolvement of nurses and allied health professional roles. These changes require health professionals to become self-directed learners who actively seek to escalate their skill and knowledge acquisition, and readily embrace change, so that they are equipped to work with a conglomerate of private companies with boundaries that are not constrained. The sheer diversity of where, how and when care is delivered has led to an explosion of new roles, reshaping and challenging of older roles and traditional stereotypes.

Activity 9.1

Consider the following

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of following the traditional career pathway?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the new multiple access routes to working in healthcare?

- Do you feel equipped to support the diverse range of students entering the healthcare profession?

- What could you do to improve your ability to equip new students with knowledge and skills required for this diverse range of roles?

Front Line Care (DH 2010a) suggests a number of recommendations:

- Improving the quality of patient care

- Improved health and wellbeing for nurses and midwives

- Recognition of the nurse’s role in caring for patients with long-term conditions

- Promoting innovation and leadership

- Promotion of an all-graduate profession

- Provision of a career framework to support nurses through clinical practice, education and research

- Nurses and midwives educated to care

It is not clear how these ambitious plans can be achieved when set against the backdrop of financial cutbacks. The promotion of lifelong learning, training, education and the continual develop of skills and knowledge required by professionals in today’s healthcare environment will cost money. Many existing staff are not educated to degree level and will need their skills and knowledge to be increased in order that they can mentor future healthcare staff to the appropriate level.

Generic Frameworks and Policies for Career Progression

The NHS Next Stage Review carried out by Lord Darzi on behalf of the labour government (Darzi 2008) put the emphasis on practitioners being ‘practitioners, partners and leaders’ during their career. This report came during a time of unprecedented change and remodelling of the healthcare economy, with the move from acute to community care and the emphasis on patient involvement and empowerment as well as increased innovation and efficiency, skill mix within teams and a need for patient safety. The need for practitioners to take part in other areas of the healthcare economy as well as clinical care was seen as a safeguard to ensure that the patient would always be at the forefront of service delivery and that the clinical staff were more likely to have the clearest focus on what was best for patients. A growing mistrust of managers and the medical professions has become evident with the separation of general practice from primary care and the drive towards target-driven results. Darzi attempted to adjust this by putting clinical staff at the forefront of the decision-making processes. This was already something that was taking place within practice and clinical staff were often tasked with taking on management and leadership roles, not necessarily willingly. However, the acknowledgement of this as being important and that other avenues might enable staff to contribute significantly to patient care, as well as just a clinical career pathway, was a refreshing change for many professions. For the first time it was acknowledged that clinical staff could take on other and often dual roles that would not take them away from influencing positive outcomes for patient care.

The ever-growing need for safety, governance and efficiency became an attractive avenue for experience practitioners to be able to travel in their career development. This enhanced the clinical side of their roles, if the clinical aspects of their role had been maintained or allowed the practitioner to contribute to practice from their very considerable ‘on the ground’ experience. A long hard look at the nature of healthcare by the government resulted in the question of whether healthcare practitioners are being given the opportunity and motivation for developing, retaining and practising the skills that are required for such a complex healthcare economy. The training of nurses had come under the spotlight in comparison to the training of nurses elsewhere in the European community, who exited their programmes as graduates, and to other health professions in the UK such as occupational therapists and physiotherapists. More allied health professionals were gaining Masters level qualifications and PhDs, professions such as paramedics and operating department practitioners were starting to get the recognition that they deserved and to be able to access undergraduate degrees after doing the initial diploma training. Although training and education for healthcare professionals moved on it became evident that higher skills, greater knowledge and specialisation within their field might also allow practitioners to transfer from one setting to another, e.g. from a leadership setting in a clinical environment to an academic or research setting.

This was previously seen as a rather derogatory move with a feeling often articulated by clinical staff that the skills of the clinical environment would be wasted in an educational one. The recognition that skills were transferable from one setting to the other was strengthened with the Agenda for Change (AfC) system that allowed for better links between pay and career progression using the Knowledge and Skills Framework (DH 2004). This Framework mapped skills against job roles and set levels of expectation for the skills of those who were in those roles. There followed a plethora of advice, guidance and policy documents on ‘career development’ of all kinds. including the report of the Prime Minister’s Commission on Nursing (DH 2010b) which attempted to set the agenda for the development of the profession as an all-graduate profession. This looked solely at nursing and made recommendations for the focus and development of the professions to meet the needs of healthcare in the future. The following provides a brief overview of the other major document to which we refer in the discussion on professional development for healthcare practitioners. These documents can also be used as a resource for planning your own future career and skills development, in addition to the Knowledge and Skills Framework, role-specific frameworks such as the Interprofessional Capability Framework (see Chapter 7 for more information), and any professional competency and skills development frameworks.

General Frameworks

The Clinical Career Educational Framework was developed by NHS Education Scotland in 2009 after publication of the Modernising Nursing Careers document (DH 2006). The Framework endeavours to highlight the possibility of transferability of skills, especially those that are related to educational delivery and to demonstrate how clinical and educational roles can be integrated and utilised to enhance career development. A number of interesting exemplars are used to show how others have used their skills to move between roles in similar and different organisations, to move between clinical and education roles, or to hold roles where elements of both of these have been a feature. It is hoped that this will allow greater flexibility for practitioners in an environment that is becoming increasingly demanding and where multi-tasking is the norm.

The following are the key features of the Framework:

- The Framework adopts a principles based approach for transforming and embedding clinical education careers.

- The Framework relates to strategic drivers and national frameworks.

- The Framework recommends educational preparation to support career planning, and regulatory and educational quality assurance mechanisms.

- The Framework describes broad capabilities and spheres of responsibility.

- The Framework recognises roles with a specific remit for education as well as those where education is integral to another role.

- The Framework supports both horizontal and vertical career progression including movement between service and educational organisations.

Although this framework has been developed for NHS Education Scotland, it is a useful and relevant tool for those working throughout the UK. Predominantly developed for nurses to enable them to consider the possibilities that their particular skills give them, it does give some good examples of roles that could be filled by allied health professionals in similar education or clinical roles. The Framework demonstrates horizontal and vertical development of practitioners.

Modernising Nursing Careers (DH 2006) is also based on nursing roles and considers the professional development and future direction of the nursing professions. Unlike the Clinical Career Educational Framework, there is no development framework that this document is based on; it is more of a strategic acknowledgement that nursing careers must be flexible and innovative enough to respond to the needs of modern healthcare and patient choice. The document focuses on the change in education, healthcare and public perception of nursing that is required to bring nursing into the twenty-first century.

The following are the key features of Modernising Nursing Careers:

- Development of a competent and flexible workforce

- To update career pathways and career choices

- To prepare nurses to lead in a changing health system

- Modernising the image of nursing and nursing careers.

It is envisaged that these goals and aspirations would be done not through one or two major initiatives, but as themes that run through policy and practice development, both strategically at a high level and percolating down to local levels. This would be expected to reach service delivery areas, educational institutions, commissioning arrangements, financial planning and workforce design. Within the document, as the Clinical Careers Educational Framework, are a number of exemplars that demonstrate career development of practitioners and the range of different pathways travelled by them. These exemplars are useful in allowing practitioners to think creatively about career trajectories.

Modernising Allied Health Professional Careers: A competency based career framework (DH 2008b) is exactly that. The same drivers that encouraged the previous two documents led to this framework that consisted of a strategically led document commissioned by the Department of Health and a web-based tool researched and developed by Skills for Health (2008). The framework is for allied health professions, excluding paramedics whose competencies are included in the curriculum and competence document for emergency care practitioners. Although the need for flexibility is championed to ensure patient-centred and responsive healthcare delivery, there is no recognition of the need for a culture change which mirrors that required in nursing to bring the professions up to date. This may be due to the fact that many allied health professions (AHPs) are already all-graduate professions and those that are not, such as operating department practitioners and paramedics, are young professions in terms of their members being registered professionals. These two professions have developed significantly over the last few years and have responded to service change while evolving as an emerging profession. Basic qualifications for these professions have rapidly evolved from City and Guilds qualifications to diplomas and foundation degrees. Work continues to offer undergraduate degrees as entry to the profession and to develop higher degrees for qualified practitioners. The flexibility of AHP careers is as essential as nursing careers, but new professions seem less held back than nurses by ‘tradition’ as public perception. Whether the development of paramedic BSc undergraduate degrees as the only entry to the professions will attract the ferocity associated with the development of nursing as an all-graduate profession remains to be seen.

The key feature of the document is that the framework is designed to maximise the contribution that the AHP can make to transforming healthcare for the benefit of patients, by providing a patient-centred approach to:

- role and service development

- career development

- education planning, commissioning and delivery.

The Skills for Health web-based tools can be used by the following.

Service managers and planners to define the competences that services, teams and individuals must have in order to meet patient needs, and to develop roles, teams and services that reflect these needs.

Clinicians and support staff to define their current competences and skills, and to identify areas for development and potential career pathways.

Education planners and education commissioners to identify the development needs of allied health professionals, and to plan and provide training and development that meet these needs.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree