22. Care of patients requiring vascular surgery

Shelagh Murray Hall

CHAPTER CONTENTS

Introduction463

Physiology of circulation464

Arterial occlusive disease465

The patient with chronic ischaemia468

Nursing assessment of patients with peripheral vascular disease472

Management of the patient with chronic limb ischaemia474

Acute leg ischaemia483

Management of the patient requiring lower limb amputation485

Management of the patient with an abdominal aortic aneurysm490

Management of the patient requiring carotid endarterectomy494

Management of the patient with varicose veins496

Introduction

Vascular disease is now a leading cause of death in Western societies. Varicose veins are the

commonest disorder presenting to surgeons, and an average of 30% of district nursing time is spent caring for patients with venous leg ulceration (Laing, 1992). Most arterial vascular disease is a consequence of atherosclerosis. Epidemiological findings have shown that the prevalence of peripheral arterial occlusive disease (PAOD) is high and that it also has a high socioeconomic impact (Kannel and McGee, 1985).

On completion of this chapter the reader will be able to:

• describe the basic physiology of circulation

• discuss the process of atherosclerosis as the underlying cause of arterial vascular disease

• describe the nursing assessment of patients with peripheral vascular disease

• list the diagnostic investigations and radiological/surgical interventions required for patients with vascular problems

• describe the care requirements for patients undergoing various types of vascular surgery

• identify the care required for patients following lower limb amputation

• discuss the care required for patients with varicose veins

• describe the challenging and complex care, and education required to help reduce risk factors and progression of peripheral vascular disease.

Peripheral arterial occlusive disease is a debilitating chronic condition which can significantly affect quality of life. Early primary care detection and treatment of the adverse effects of the underlying disease process is essential, as the REACH registry (Bhatt et al, 2006) has shown that vascular disease continues to be poorly controlled and undertreated.

Care of patients with established PAOD is both challenging and complex. It involves early detection, ongoing monitoring, as well as knowledge of new developments in diagnostic, radiological and surgical procedures. A major component of care must include measures to reduce the progression of atherosclerosis, which requires a multidisciplinary team approach to achieve successful outcomes.

Physiology of circulation

Blood flow is essential to human life, and blood is circulated to all areas of the body by the pumping action of the heart. Blood flows through arteries, veins and capillaries which compose the vascular bed. Arteries and veins are composed of three layers:

• tunica intima – inner layer of endothelium which provides a smooth passage for blood to flow

• tunica media – middle layer consisting of muscle and elastic tissue which regulates the diameter of the vessel by dilatation and constriction

• tunica adventitia – outer layer of fibrous tissue which gives the vessel support to maintain its shape.

The arterial system

The arterial system is responsible for carrying oxygenated blood and nutrients to the body tissues. Arteries help to regulate the blood pressure by expanding with each surge of blood ejected from the heart and then resuming their original diameter.

The arteries branch off into smaller arterioles, which subdivide into the capillary network. The arterioles differ from the larger arteries in that the tunica media layer consists almost entirely of smooth muscle. Blood has to pass through precapillary sphincters before entering the capillary network. These sphincters work in conjunction with the autonomic nervous system to regulate the perfused capillary bed. The capillaries form a network to link the smallest arterioles to the smallest venules.

Capillaries are the simplest of the blood vessels; their walls consist of a single layer of endothelial cells, which have a semipermeable membrane. The capillaries make up the microcirculation, which allows the exchange of nutrients and waste products from the surrounding tissues. When the smaller arteries constrict, there is an increase in peripheral vascular resistance. This is a measure of the friction between the molecules of the blood and the radius and length of the blood vessel. The smaller the radius of the vessel, the greater the resistance to the flow of blood, so altering blood flow.

During vasodilatation of the artery, there is a decrease in diastolic blood pressure and in peripheral vascular resistance, so increasing blood flow.

There is increasing evidence of the important function of the inner layer of the endothelial cells and its role in the development of vascular disease. The endothelium provides a cellular lining to all the blood vessels in the circulatory system and acts as an interface between the blood and the vascular wall. There is evidence that the vascular endothelium helps preserve cardiovascular homeostasis. The blood’s fluidity is maintained by the antiplatelet, antithrombotic and antifibrinolytic properties of the endothelium, and damage to the endothelium disturbs its function, leading to vasospasm, thrombosis and atherosclerosis (Jones, 2001).

The venous system

The venous system originates in the capillary beds to form venules, which are responsible for removal of waste products from the capillaries. The venules merge to form veins, which carry deoxygenated blood back to the heart.

Veins

Veins have thinner walls, less muscle and elastic tissue, and lie closer to the skin surface than do arteries. Veins also differ in that some, mostly in the limbs and especially the lower limbs, have endothelial valves. These permit blood flow only towards the heart, preventing reflux. The return of blood to the heart is therefore reliant on three factors: patency of the veins, valve competence and contracting surrounding muscles (muscle pump). During exercise, the veins in the leg are compressed by the contracted leg muscles, which act as a ‘muscle pump’, so allowing blood to be returned towards the heart. Blood is returned from the lower limbs to the right side of the heart via the inferior vena cava by the pumping action of the muscles. This pumping action from the calf and foot muscles compresses the deep veins of the legs, which contain one-way valves, and pushes the blood back to the heart, with backflow being prevented by the valves. These muscular contractions allow emptying of the blood from the superficial veins into the deep veins, via the communicating vessels. The venous system of the leg comprises a superficial system in the skin and subcutaneous fat, and a deep system beneath the fascia. The main superficial leg veins are the long and short saphenous, which form a venous network with other perforating veins, which pass through the fascia to join the deep veins. These deep veins run alongside the arteries and have the same names.

Lymphatic vessels

Lymphatic vessels are thin-walled vessels which arise at the capillaries and also branch into their own circulation. Lymph capillaries, like veins, increase in size and, with the assistance of valves and muscular contractions, transport excess interstitial fluid (lymph) to the venous system via large ducts in the thoracic cavity. Through these ducts, the lymph flows into the inferior vena cava and subclavian vein and finally into the right atrium, where it is recycled into the central circulation. Lymphatic vessels are highly permeable, with large pores which allow the removal of proteins, cellular debris and fat absorption from the intestines. Lymph nodes are situated along the lymphatic system and filter debris from bacteria, viruses and other refuse from lymphatic fluid.

Arterial occlusive disease

Arterial occlusive disease may occur suddenly, following an embolus or thrombus, or insidiously, as in atherosclerosis.

Atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis is the underlying cause of peripheral arterial occlusive disease and affects 5–10% of the population over 55 years of age. It mainly affects the aorta, arteries to the lower limbs, and coronary, carotid and renal arteries. Common sites include the aorto-iliac, femoral, popliteal and tibial arteries.

Atherosclerosis is a process which often begins in childhood and is not, as previously thought, a slowly progressive disease (Libby et al, 1996). Changes within the arterial wall are identified in three stages:

1. Stage of fatty, lipid streak formation within the intima.

2. Stage of fibrous plaque formation in the subintimal layer, which extends along the artery walls and then protrudes and narrows the lumen.

3. Stage of complication – characterized by endothelial ulceration, calcification, and activation of platelets and leucocytes, leading to thrombus formation.

The process of atherosclerosis results in the arterial walls becoming thickened and hardened, with loss of elasticity and decreased blood flow. After the age of 30 years old, the atheromatous plaque formations become more pronounced, causing symptoms when the artery lumen becomes narrowed by more than three-quarters (Shah, 1997). This, in turn, may lead to thrombosis or emboli, causing ischaemia and a risk of gangrene.

Atherosclerosis may play a role in contributing to aneurysm formation, although the true aetiology is thought to be multifactorial. The artery wall becomes weakened, causing a local dilatation of the artery, which can contain thrombus. The aneurysm may rupture as it grows larger and the blood vessel wall becomes thinner, resulting in severe haemorrhage or death. Aneurysms can occur throughout the arterial tree; the most commonly affected vessels are the aorta and iliac arteries, followed by the popliteal arteries.

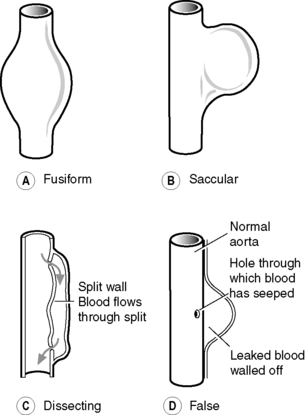

Aneurysms are classified as true or false. A true aneurysm occurs when the artery wall becomes dilated and thin but remains intact (Fig. 22.1A–C). Thrombi can collect between the layers of artery, causing a local dilatation. A false aneurysm occurs due to trauma of the three layers of artery wall, which allows blood to leak extravascularly (Fig. 22.1D). Clot formation occurs, and the clot becomes surrounded by periarterial connective tissue; blood then passes into the sac as it flows along the lumen of the artery (Greenhalgh, 1990).

|

| Figure 22.1 • Types of aneurysm. |

Risk factors

Age and gender

Symptomatic PAOD is commoner in men and also occurs earlier, the incidence being twice as high as than women <60 in men under 60 years old (Kannel et al, 1970). Female sex hormones are thought to account for this difference, as symptomatic disease is more common postmenopause (Sans et al, 1997).

Smoking

It is considered proven that smoking is the most preventable cause of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Nicotine and carbon monoxide have been shown to produce endothelial injury, leading to the development of atherosclerotic plaque in the arteries (Powell, 1991). Quitting smoking will reduce the risk of developing PAOD (Bowlin et al, 1994), and studies have shown evidence of reduction in disease progression within 3 months (Seltzer, 1989). Smoking also enhances the effect of other risk factors such as hypertension and hyperlipidaemia (Pasternak et al, 1996). Smoking should be stopped and patients informed of the harmful effects of nicotine on their condition. The majority of smokers with PAOD are nicotine addicts and require counselling and behavioural support therapy. In addition, nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion or varenicline tartrate can help relieve cravings and withdrawal symptoms in order to successfully quit.

Hyperlipidaemia

Hyperlipidaemia and hypercholesterolaemia are recognized risk factors for atherosclerosis. A high dietary intake of saturated fat is known to contribute to a high blood cholesterol, and hyperlipidaemia is known to have a congenital factor (Oliver, 1991). In addition to a healthy low-fat diet, lipid-lowering therapy (statins) improves endothelial function. Irrespective of cholesterol levels, the Heart Protection Study strongly recommends that all patients with PAOD should be treated with a statin to reduce vascular mortality (Collins, 2002). Weight reduction will also benefit obese patients with intermittent claudication, as this reduces the workload on the lower limbs.

Diabetes

Peripheral arterial occlusive disease is a major complication of both insulin-dependent and non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (Beach et al, 1988). Diabetics are more susceptible to atherosclerosis due to calcification of the medial lining of the arteries (Edmonds and Foster, 2005). Neuropathy is also common, which causes a lack of sensation, making the diabetic prone to trauma, resulting in foot injuries, infections and non-healing ulcers. Diabetic leg ulcers are usually situated on the bony prominences of the feet, resulting in necrotic wounds. Good blood glucose control reduces the risk of small vessel limb disease.

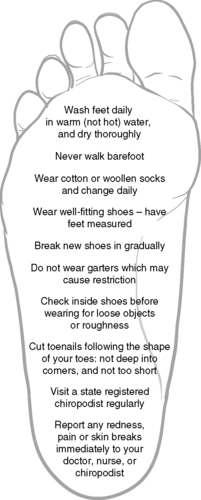

Foot care advice should be given to all patients with arterial occlusive disease, not only diabetics, to help reduce the incidence of injury, and followed up with an information leaflet to aid concordance (Ley, 1993). The nurse can help educate the patient by teaching them how to perform self-assessment and foot care (Fig. 22.2). Patients should be instructed to check their feet daily or, if they are unable to do this for themselves, a relative or carer will need to be taught how to do this. The importance of contacting their nurse, doctor, foot clinic/podiatrist immediately if problems occur should be stressed.

|

| Figure 22.2 • Foot care advice. |

Hypertension

Hypertension has been associated as a risk factor with generalized vascular diseases as well as peripheral occlusive disease (Kannel and McGee, 1985). Increased mechanical stress due to higher blood pressure can result in endothelial damage to the artery wall. Screening, advice and treatment to maintain blood pressure below 140/90 mmHg is recommended by the British Hypertension Society (Williams et al, 2004). Blood pressure should be taken in both arms on initial assessment. If a higher value is noted of between 10 and 15 mmHg, this may indicate an arterial stenosis on the side of the lower reading.

Hyperhomocysteinaemia

Homocysteine is a by-product of protein metabolism, and elevated levels are linked to acceleration of atherosclerosis and increase the risk of thrombosis (Boushey et al, 1995). Elevated homocysteine levels should be checked, particularly in patients under 60 years old. Daily supplements of folic acid may help reduce the risk of developing atherosclerotic vascular disease (Hankey and Elkeboom, 1999).

Alcohol

Binge drinking should be avoided and drinking kept within recommended safe limits: 3–4 units daily for men and 2–3 units daily for women.

Sedentary lifestyle

Physical inactivity is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Regular exercise combined with weight reduction is associated with lowering cholesterol and blood pressure.

Metabolic syndrome

Abdominal obesity in combination with hypertension, dyslipidaemia and glucose intolerance will result in metabolic syndrome. This increases the risk of type 2 diabetes and vascular disease (Grundy et al, 2004).

Socioeconomic factors

Social deprivation also increases risk factors for developing peripheral arterial disease, as patients from lower social classes are more likely to eat an unhealthy diet, exercise less and smoke. Unemployment and high anxiety levels have been found to contribute to development of the disease (Bowlin et al, 1994).

Combination of risk factors

Vascular diseases are generally caused by a combination of risk factors. For reasons unknown, men are more prone than women to all forms of vascular disease, especially aortic aneurysms. However, women’ss protection diminishes with age. Over the age of 70 years old, the risks are similar for both sexes (Kannel and McGee, 1985).

Statins and antiplatelet agents in risk factor modification

Patients with PAOD are high risk for a heart attack or thrombotic stroke. All patients, regardless of their cholesterol levels, should be prescribed statin therapy such as simvastatin, as this significantly reduces disease progression (Collins, 2002). An antiplatelet agent such as aspirin, or clopidogrel if aspirin cannot be tolerated, should also be prescribed for secondary prevention, to reduce viscosity of the blood and platelet aggregation.

The patient with chronic ischaemia

Clinical features

A patient with chronic ischaemia may have minimal symptoms in the early stages or may develop limb pain, ulceration or gangrene. Clinical features of arterial occlusive disease occur when there is partial or complete occlusion of the artery. The primary symptom of PAOD is intermittent claudication. The term ‘claudication’ derives from the Latin ‘claudus’, meaning ‘lame’, which was attributed to the Emperor Claudius who walked with a limp.

Intermittent claudication

Intermittent claudication is pain only induced by exercise, experienced in the foot, calf, thigh or buttock, depending on the level of arterial occlusion, when a certain distance is walked. The pain is caused by inadequate blood supply to the muscles and can vary in severity and walking distance. Walking at a brisk pace or on an incline will produce symptoms earlier. Patients frequently refer to their symptoms as an ache, heaviness or dullness of the leg muscles. Intermittent claudication may affect one or both legs, is more common in the calf and is always relieved by rest.

Patients with intermittent claudication may not experience a major handicap to their lifestyle, or their symptoms may even resolve with regular walking exercise. McAllister (1976) found that a patient with intermittent claudication had a 50% chance of symptoms spontaneously improving, a 30% chance of remaining unchanged, with 20% of patients deteriorating. Although some claudicants may initially fear limb loss, only 7 of 100 patients (6 of whom had diabetes) underwent major amputation. If the condition becomes more severe, it may lead to signs of critical ischaemia such as rest pain, ulcers and possible gangrene. In the 1950s, Fontaine classified the signs and symptoms of chronic leg ischaemia into four stages (Box 22.1). It is therefore important that patients with intermittent claudication modify their risk factors at an early stage to help prevent disease progression and also to reduce their chance of suffering a heart attack or stroke.

Box 22.1

Box 22.1 Fontaine’s classification of ischaemia

• Stage 1: asymptomatic

• Stage 2: intermittent claudication

• Stage 3: severe, persistent rest pain of the foot

• Stage 4: ulceration and/or gangrene

Rest pain

Rest pain is a chronic pain described as ‘associated with a chronic pathological process which causes continuous pain’ (Bonica 1990, cited in Twycross, 1994:17). As the disease progresses, the blood flow to the leg is reduced such that pain occurs while resting rather than induced by exercise. Patients with ischaemic rest pain initially awake at night with pain in the foot and toes. Pain is continually present when the patient is immobile and prevents sleep occurring, causing rapid deterioration in the patient’s morale. Temporary relief may be gained by hanging the limb out of bed or by sleeping in an armchair with the foot down.

Ulceration and/or gangrene

Arterial disease may ultimately result in tissue loss of the toes, foot or leg. Critical leg ischaemia is a condition which endangers the distal part of the limb, and there is a high risk that the patient will require toe or limb amputation. The symptoms and signs specified in the Second European Consensus Document on Critical Leg Ischaemia (European Working Group, 1991) are:

• persistently recurring rest pain requiring regular adequate analgesics for more than 2 weeks or

• ulceration or gangrene of the foot or toes plus

• ankle systolic pressure ≤50 mmHg in non-diabetics

• toe systolic pressure ≤30 mmHg in diabetics.

Investigations

A full medical history is taken, and a clinical examination performed, which will include an electrocardiogram (ECG) to determine cardiac function. An echocardiogram may be undertaken if surgical treatment is necessary. Full blood count, clotting screen, urea and electrolytes, blood glucose, HbA1c in diabetics and lipid screening will also be required, as well as routine urinalysis. Thrombophilia screen and homocysteine levels should also be undertaken in younger (<60 years old) patients. Chest X-ray and lung function tests are performed to identify potential respiratory problems prior to surgical intervention.

The limbs are observed for warmth, colour, sensation, movement, and any ulceration or gangrenous changes (Fig. 22.3A–D). Pallor, dusky erythema or cyanosis may be present, with absent or reduced peripheral pulses. Thin, shiny atrophic skin, thick brittle nails and hair loss on the limb may indicate poor tissue nutrition due to reduced blood supply. Capillary refill in the nails indicates perfusion time in the capillary beds; normal refill should occur within 3 seconds. The skin is prone to breakdown, especially from trauma. Tissue loss or gangrene may also be present over areas of high pressure such as metatarsal heads, dorsum of the foot and particularly the heels.

|

| Figure 22.3 • Features of critical leg ischaemia. (A) Ischaemic pallor of the sole of the foot. (B) Both feet show changes of ischaemic disease, such as hair loss, skin coarsening and ulceration. (C) Thinning and shininess of the skin around the toes, with ulceration at a pressure point. (D) Patient presenting with rest pain in both feet and gangrenous toes. (Reproduced with kind permission from Bettie Walker, on behalf of William F. Walker, from Walker (1988).) |

Peripheral pulses

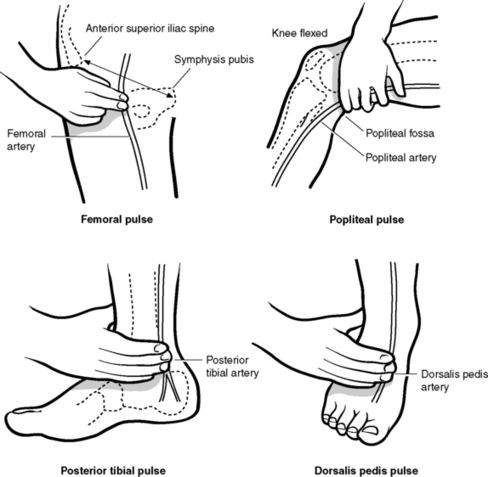

Limb pulses are palpated to assess the adequacy and volume of the blood supply at femoral, popliteal, posterior tibial and pedal pulse sites (Fig. 22.4). The absence of pulses or a weak pulse may determine the presence of arterial disease, and require confirmation by Doppler ultrasound (Moffatt et al, 1994).

|

| Figure 22.4 • Palpation of arterial pulses in lower limb. |

The presence of bruits (abnormal ‘whooshing’ sounds or murmurs) may be heard with a stethoscope. This turbulent flow, heard over major arteries, may be significant in carotid vessels which are narrowed due to atherosclerosis.

Doppler ultrasound

Doppler ultrasound is a practical non-invasive test using ultrasonic high-frequency sounds emitted from a hand-held transducer probe. It is used to assess the arterial blood supply to the lower limb by listening to the arterial sounds, and for measuring the ankle/brachial systolic pressure ratio, to aid diagnosis and detect the degree of arterial insufficiency. Doppler ultrasound can also be used to ascertain the presence of pedal pulses following intervention such as angioplasty, thrombolysis or reconstructive bypass surgery.

The highest systolic pressure in the arm at the brachial artery is compared with the highest systolic pressure in the ankle at the dorsalis pedis and the posterior tibial artery, to give an ankle–brachial pressure index (ABPI):

• normal ABPI ≥1.00

• ABPI for patients with claudication = 0.5–0.9

• ABPI for patients with rest pain and critical leg ischaemia ≤0.5.

The lower the ABPI, the greater the arterial impairment. However, false high readings may be obtained in patients with diabetes, atherosclerosis, and chronic renal disease, as a result of calcification of the arteries, which means the sphygmomanometer cuff cannot fully compress the hardened arteries.

ABPI is also known to be a predictor of survival in vascular patients; the lower the ABPI, the higher the risk of vascular mortality (McDermott et al, 1994).

Toe pressures

Measurement of toe pressures can be performed to assess arterial blood flow in diabetics by using photoplethysmography (PPG). A special small occlusion cuff is usually attached to the first toe, and the PPG sensor uses changes in infrared light to detect blood flow. This technique is feasible because distal pedal vessels in diabetics are less calcified and incompressible than ankle vessels.

Colour duplex scan

Duplex ultrasonic scanning of the arterial tree with colour flow imaging is a non-invasive technique used to provide more accurate diagnosis of stenosis or occlusion from the aorta to the tibial vessels. The scan demonstrates the direction of arterial or venous blood flow using an ultrasonic probe and displays it as a colour. An increase in velocity of the flow and colour change occur where there is a stenosis. It is usually possible to detect whether a lesion is suitable for balloon angioplasty, and, in most centres, duplex scanning has replaced the need for more invasive diagnostic angiography.

Computerized tomography

Computerized tomography (CT) scanning uses a rotating X-ray source which allows individual slices to be obtained. Spiral CT can also be used and allows continuous rotation while the patient moves through the X-ray beam. A CT scan is useful in the diagnosis of aortic aneurysms, but the contrast medium used can cause problems in patients with impaired renal function.

Magnetic resonance angiography

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is a non-invasive scan. This technique is particularly useful to more accurately detect the size and extent of atheromatous lesions and where patients may be at risk from invasive angiography. MRA is also useful to screen patients for an aortic aneurysm.

Angiography

A radio-opaque contrast medium is injected into an appropriate artery, and a series of X-rays is taken of the arteries, demonstrating filling of the vessels and any narrowing or stenosis. A femoral artery approach is normally used to investigate lower limb arteries.

Angiography is usually performed under a local anaesthetic and can be undertaken on a day case basis, depending on the age, social circumstances and clinical condition of the patient. Sedation or general anaesthesia may occasionally be required for very anxious patients. Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) allows greater clarity of the arteries (Belli and Buckenham, 1995). This is a computerized method of angiography without background information, e.g. bones and bowel.

Specific preparation of the patient prior to angiography

• The patient should be fully informed of the length of the procedure and that the injection of dye causes a sensation of heat and some discomfort.

• Fasting is not required prior to angiography. The bladder should be emptied beforehand, as the patient needs to lie very still during angiography.

• Intravenous prophylactic antibiotics will need to be given immediately prior to the procedure in patients with previous synthetic bypass grafts or stents, to prevent infection.

Aftercare

• Patients are at risk from haemorrhage, haematoma formation and development of arterial occlusion. Following the procedure, pressure is applied to the puncture site to prevent haemorrhage when the catheter has been removed.

• The patient should be nursed relatively flat in bed and instructed to keep the affected limb straight for 4–6 hours post-procedure, depending on the catheter size used.

• Observations of pulse and blood pressure are undertaken using an early warning score (EWS) system for vital signs:

– ¼ hourly for 1 hour

– ½ hourly for 2 hours

– hourly for 1 hour

– 4 hourly overnight (non-day care patients).

• Observation of foot pulse, colour, temperature, limb movement and sensation should also be made at these times and the puncture site carefully monitored for haemorrhage or signs of haematoma formation. The patient should be informed to call the nurse immediately if any bleeding occurs at the puncture site.

• The patient should be encouraged to drink at least 2 L of fluid in order to flush out the contrast medium from the kidneys.

Nursing assessment of patients with peripheral vascular disease

Nursing assessments are generally undertaken in a vascular pre-admission clinic for those being admitted for a planned procedure. Patients being admitted to hospital will be experiencing either moderate or severe problems which may interfere with their activities of daily living. The impact of the varying stages of the disease is demonstrated within the framework of the Activities of Living model of nursing of Roper, Logan and Tierney (Roper et al, 1981). A functional assessment to identify the patient’s self-care ability and lifestyle handicap is undertaken. Guidelines for these stages of the nursing process together with planning and implementing care have been included under each activity.

Maintaining a safe environment

There is a potential risk of further deterioration in the blood flow to the limbs following admission. Patients with advanced arterial insufficiency are also at risk of developing breaks/ulceration to the skin’s integrity, especially the sacrum and heels (Fig. 22.5). This risk is significantly increased in patients with severe ischaemic rest pain who have been immobile, and may also have been sleeping in an armchair at night to try to relieve their pain.

|

| Figure 22.5 • Pressure ulceration and gangrene of heel. |

Initial limb assessment should be documented, and regular observations recorded for patients with severe ischaemia:

• the colour, warmth, sensation and movement of both limbs should be compared

• the dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses should be checked with a Doppler and compared with those in the other limb.

A risk assessment of the patient’s skin should be undertaken within 6 hours of admission (RCN, 2004), paying particular attention to the lower limbs. The skin should be observed for dryness, infection, oedema, ulceration and gangrenous changes. Detection of any breaks or abnormalities should be reported and documented on a wound assessment chart. Skin ulceration is more commonly found on the toes, malleoli and heels in patients with advanced disease.

A reliable and valid assessment tool should be used to determine the patient’s risk of developing pressure ulcers, so that an appropriate pressure-relieving mattress, seating and heel protection pads can be provided (Waterlow, 1988). Patients with rest pain may well present with a high risk score on admission. Chair nursing should be kept to a minimum and pain relief regularly reassessed to allow the patient to sleep in bed.

All patients presenting with leg ulcers must undergo a full holistic assessment and Doppler assessment to help determine the underlying aetiology of the ulcers.

Communication

Nursing assessment should consider patients’ psychosocial needs and also take account of their spiritual and ethnic requirements. Any social service requirements for home support on discharge, or advice regarding benefit/mobility allowances should be assessed and communicated to the appropriate members of the multidisciplinary team, ideally prior to admission to hospital.

Patients may have fears and anxieties about forthcoming procedures. They may also experience varying degrees of pain which may not be adequately communicated to the nurse. Patients with severe ischaemia may also fear limb loss as a possible outcome. Social isolation is a common problem in patients with severe disease affecting their quality of life. The nurse should be aware of factors such as poor mobility, pain, and smoking and drinking habits, which can contribute to a patient’s isolation.

Allowing time and privacy for open discussion and providing sufficient information/explanation of proposed procedures will help to allay anxieties. It will also assist patients to make choices about their care and consider any alternatives of treatment. Evaluation of the patient’s understanding of their condition is vital to ensuring informed consent and to facilitate active involvement in care and recovery. Verbal information should be reinforced where possible with leaflets on various aspects of vascular conditions and treatments.

Breathing

Breathing may not be compromised. However, these patients are often lifelong heavy smokers, and this factor, together with restricted mobility in some, will increase the risk of developing chest infections. An increase in respiratory rate and/or production of sputum, as well as any shortness of breath on exertion, should be monitored. Baseline respiratory rate and oxygen saturation levels should be documented.

Eating and drinking

Nutritional and hydration status is a high priority. A baseline admission weight and body mass index (BMI) should be documented. The debilitating effects of severe rest pain and consequent reduced mobility may have resulted in the patient relying on convenience snacks at home. Heavy smokers may also have had appetite suppression, and alcohol intake should be assessed.

Patients with diabetes may require review of their dietary intake, as poorly controlled diabetes will escalate the onset of foot complications and delay postoperative wound healing. Patients who have raised blood cholesterol may also require review of their dietary intake of fat.

A full nutritional assessment by the dietitian will be needed if malnutrition is suspected, as problems such as electrolyte imbalance, delayed wound healing and sepsis can influence the morbidity and mortality of vascular patients.

Eliminating

Poor mobility due to severe ischaemia may prevent the patient from reaching the toilet. Routine urinalysis should be performed to check for glucose, ketones and protein. Urine output should be monitored, as vascular patients frequently have renal impairment. Constipation may arise in patients with ischaemic pain having regular analgesics, particularly morphine; therefore, an aperient should always be prescribed.

Dressing and cleansing

Again, limited mobility and pain may have affected the patient’s ability to wash and dress independently.

Controlling body temperature

Temperature on admission should be checked, as elderly patients living alone who have a critically ischaemic limb may have hypothermia. Pyrexia may be an indication of chest, wound or graft infection, or due to limb ulceration or cellulitis.

Mobilizing

Pain is the main factor in reducing the patient’s mobility; this is affected to a lesser or greater degree by the extent of the arterial occlusion.

Patients experiencing claudication pain on walking may have only minimal inconvenience to their normal mobility and lifestyle, whereas those affected by rest pain due to severe arterial occlusion and/or ulceration may be totally unable to bear weight on the affected leg.

The following information needs to be obtained during assessment:

• Is the pain related to exercise and is it relieved by resting?

• Does the pain occur in the foot, calf, thigh or buttock on walking, and how far can the patient walk before experiencing pain?

• Does the pain occur at rest and prevent the patient from sleeping at night?

• How has the pain been managed and what analgesics are taken?

• Has the patient had any problems with walking, and have walking aids been required?

Visual pain analogue assessment tools are essential to help establish the severity and type of pain, its effect on the patient and the effectiveness of prescribed analgesics.

Ensure that footwear is appropriate and does not cause undue pressure. This is especially important for diabetic patients, where there is an increased risk due to neuropathy. Special surgical shoes are available to help accommodate wound dressings to the foot.

Working and playing

Depending on severity of symptoms, occupation or hobbies will inevitably be affected in patients with intermittent claudication, whereas reading or watching television may become a strain for those with rest pain.

Sexuality

A male patient with claudication may suffer impotence due to internal iliac artery occlusion, and this may also be a complication following surgical repair of an abdominal aortic aneurysm.

Sleeping

Sleep patterns are often disturbed by severe limb pain, either by waking the patient suddenly or by preventing sleep occurring. Hanging the affected limb out of bed, or sleeping in an armchair with feet down may provide temporary pain relief but will increase leg oedema.

Dying

Some patients may express anxieties regarding proposed major surgery which may be necessary to save a critically ischaemic limb, or prevent stroke or rupture of an aortic aneurysm.

Management of the patient with chronic limb ischaemia

There are no immediate plans for a specific National Service Framework for peripheral vascular disease; however, initiatives have been instrumental in targeting priority areas, which include heart attack, stroke prevention and diabetes (Department of Health, 1999, Department of Health, 2000, Department of Health, 2001a, Department of Health, 2001b, Department of Health, 2006 and Royal College of Physicians Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party, 2004). Screening, prevention and reduction of peripheral vascular disease require the same high profile afforded to other conditions which share similar risk factors, such as coronary artery disease and stroke. Likewise, equal emphasis for reducing the incidence of disease progression and limb amputation in patients with arterial disease, as given to diabetics, should be encouraged amongst all healthcare professionals. Variations in patient management still exist as there are no quality outcome frameworks (QOF) to address inadequate care of these patients in primary settings.

Management and treatment of patients with arterial occlusive disease is based on each patient’s overall health condition, age, lifestyle impairment and the severity of the disease. These factors, along with the feasibility of the procedure, will influence the decision for either radiological intervention such as angioplasty or arterial reconstructive surgery to restore blood flow. Arterial occlusive disease rarely presents in isolation, and patients will often have accompanying coronary, cerebrovascular and renal disease which must also be taken into account in their management.

Nursing this patient group is therefore complex, because of their challenging health needs. Patients may have experienced intermittent claudication and walking restrictions for many years and may have high anxiety levels about their health outcomes. Many may still be breadwinners for their family or be carers for dependent relatives. Lifestyle aspects which probably contributed to their present health problems often die hard. Advances in pharmacotherapy, radiological technology and surgical techniques in the last two decades have significantly improved the prognosis for these patients, who would otherwise have faced primary amputation to alleviate rest pain and ulceration. Reconstructive bypass surgery is normally only considered for patients with critical leg ischaemia when the occluded vessel is not amenable to less invasive procedures such as angioplasty.

Management of the patient with intermittent claudication

Patients with intermittent claudication need to adapt their lifestyles to comply with the risk factor modifications previously discussed. Social, environmental and lifestyle factors are known to be significant risk factors, independent of others, for development of the disease in men (Bowlin et al, 1994). Management requires an individualized and holistic approach, focusing on health education, physical and psychosocial needs. Concordance and control may depend upon a patient’s social and cultural situation, which will influence their health behaviour (Ewles and Simnett, 2003).

If claudication is mild or moderate and does not significantly impair the patient’s lifestyle, the first line in management is now exercise and best medical therapy/risk factor modification. Intervention such as angioplasty may be indicated for more moderate to severe claudication; however, the benefits remain controversial where best medical therapy and exercise produce similar outcomes (Perkins et al, 1996).

Lifestyle and risk factor management of intermittent claudication

The role of the nurse in providing holistic care is of vital importance, as promoting a healthy lifestyle will enable patients to make lifestyle choices to try to improve their own health and quality of life. Influencing lifelong health beliefs and smoking, eating and exercise habits in this patient group provides a challenge to the nurse. The nurse, whether a novice ward nurse or an experienced nurse specialist running nurse-led services, will need to gain the patient’s active participation in decision-making and actions in order to bring about change to slow disease progression. Factors affecting adherence and understanding of a patient’s self-motivation are essential in effecting changed behaviour. Control of this chronic condition and prevention of complications will depend on the careful assessment of the patient’s risk factors as discussed earlier, and strategies to manage them, especially smoking.

Medication concordance is vital, and patients should be advised of the importance of taking medications regularly, such as antihypertensives, diabetic drugs, statin and antiplatelet therapy. The latter medication, such as aspirin, reduces the frequency of thrombotic events in peripheral arteries and reduces overall cardiovascular mortality in claudicants by reducing blood viscosity (Antithrombotic Trialists Collaboration, 2002).

Stress management is also important, as the body’s response to life pressures and anxieties is to release adrenaline (epinephrine), which increases the heart rate, blood glucose and cholesterol levels. Consequently, the body becomes stressed, resulting in hypertension, which eventually contributes to the development of atherosclerosis. Teaching the patient stress management strategies, such as relaxation techniques, taking regular exercise and avoiding excessive alcohol or food consumption, is equally important.

Exercise therapy for intermittent claudication

Exercise is the mainstay of treatment for patients with claudication and has been shown to improve pain-free walking distance (Hiatt et al., 1991, Lungren et al., 1988, Patterson et al., 1997 and Perkins et al., 1996). It aids in the development of collateral circulation, which may help prevent ischaemia in the affected leg. A Cochrane Review recommends exercise as a key component of management of intermittent claudication (Leng et al, 2002). However, it has yet to be established what an ideal exercise programme should be, although supervised, structured programmes are more beneficial (Bendermacher et al., 2006 and Cheetham et al., 2004). In addition, walking exercise of 30 minutes at least three times a week, and walking to near-maximal pain, will achieve greatest improvement in patients (Gardner and Poehlman, 1995). The TASC working group (2000) recommends that exercise therapy (preferably supervised) should always be considered as part of the initial management of patients with intermittent claudication. Despite the evidence and recommendations, supervised programmes are not readily available in primary or secondary health settings. Some patients may not be willing to wait for symptom improvement with exercise, or are more likely to not have access to suitable programmes.

Endovascular intervention

Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty

Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) has become an established treatment for moderate to severe claudication, limb-threatening disease with ischaemic rest pain and to help facilitate healing of ischaemic ulcers. Angioplasty is performed under local anaesthesia and therefore carries a lower overall risk than surgery. Recent advances in technique have made day case angioplasties possible in some centres for patients with intermittent claudication (Cleveland et al, 2002).

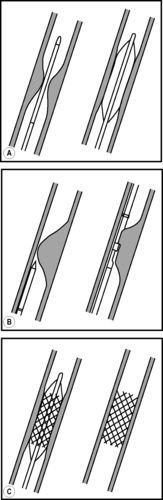

Short stenosis or occlusion of iliac, femoral and popliteal arteries can be effectively treated by angioplasty. The procedure involves the insertion of a balloon catheter, which is passed into the lumen of the vessel, usually via the femoral artery, under local anaesthesia. The catheter is advanced to the site of the atheromatous plaque, and the balloon inflated, dilating the stricture, and hence improving the patency of the lumen of the vessel (Fig. 22.6A).

|

| Figure 22.6 • (A) Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty. (B) Atherectomy. (C) Stent insertion. |

Other techniques such as atherectomy and insertion of stents can be combined with angioplasty. Atherectomy (Fig. 22.6B) uses high-speed revolving cutters to cut and remove an obstructing thrombus, whereas expandable metal stents can be inserted to prevent restenosis at the angioplasty site (Fig. 22.6C).

Preparation of the patient prior to percutaneous transluminal angioplasty

• Nursing care and preparation are similar to that provided prior to angiography, except that the patient should be fasted for 2–3 hours prior to the procedure in case complications arise, such as thrombosis/embolus or rupture of the vessel wall, which will require surgical intervention.

• During angioplasty, patients will be required to lie still for a long period of time and therefore will require pressure-relieving aids to prevent skin breakdown of their sacrum and heels if they have severe limb-threatening disease. Pressure on the heel, even for a short time while lying on the X-ray table, can lead to pressure ulceration and necrosis.

Aftercare

• Aftercare is also similar to that following angiography. However, the nurse must be aware of the increased risk of haemorrhage, haematoma or thrombosis, and should report any such occurrences immediately. Pedal pulses should ideally be located using the Doppler ultrasound probe.

• Continued pressure relief for sacrum and heels will be required throughout the period of bedrest in high-risk patients.

• Health education advice should be reinforced before the patient is discharged, and, if necessary, advice given for self-referral to a Stop Smoking Clinic. Walking exercise should be encouraged to develop collateral circulation.

Reconstructive bypass surgery

Patients with ischaemic rest pain, ulceration or gangrenous lesions will require surgical intervention if less invasive treatment is not possible, since, if left untreated, most patients with critical ischaemia will eventually require amputation.

Arterial reconstructive surgery can enhance the quality of life for patients with limb-threatening disease, although outcomes can be less predictable. It is therefore essential to be aware of the patients’ expectations, because, if surgical revascularization fails, an amputation will be necessary. However, long term results (Bradbury, 2007) from the BASIL trial (Adam et al, 2005) have shown that patients with severe ischaemia who have ‘initial’ (or ‘primary’) bypass without previous angioplasty have an improved amputation-free survival and a lower mortality rate.

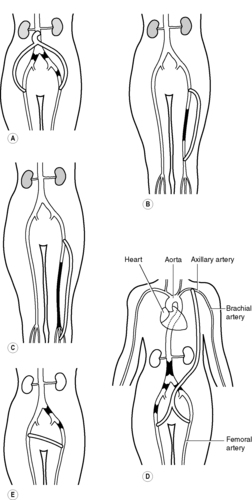

Revascularization methods depend on the location and extent of the stenosis/occlusion (Fig. 22.7). Restoring blood flow entails bypassing the stenosed or occluded artery using synthetic graft material or the patient’s own long saphenous vein. Vein grafts are the preferred conduit as they have a superior patency rate and decrease the risk of infection (Beard and Gaines, 2001). Patency rates for prosthetic grafts used in narrower more distal arteries in the legs are poor. The operative procedure involves anastomosis of the graft from an area above to an area below the diseased vessel. A vein harvested from the arm can also be used if the leg veins are unsuitable. Due to the presence of valves, the vein is either reversed before insertion, to enable correct direction of blood flow, or the valves are destroyed and the vein left in situ. Synthetic grafts made from polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) are now commonly used (Fig. 22.8).

|

| Figure 22.7 • Examples of types of reconstructive surgery and types of occlusions: (A) aorto-bifemoral graft; (B) femoro-popliteal bypass; (C) femoro-distal bypass; (D) axillo-bifemoral graft; (E) femoro-femoral crossover graft. |

|

| Figure 22.8 • Examples of straight and bifurcated axillo-bifemoral PTFE grafts. |

Endarterectomy

This is the coring out of the atheromatous plug using a ring stripper inserted into the artery lumen; it is now more commonly used for common femoral or carotid artery stenosis.

Aorto-bifemoral bypass

This bypass extends from the distal aorta to the common femoral arteries and is performed for stenosis or occlusion of the aorta or iliac vessels, using synthetic graft material. Patients with aorto-iliac disease will often present with bilateral buttock/hip claudication and impotence.

Femoro-popliteal bypass

This bypass is performed for occlusion in the superficial femoral artery.

Femoro-distal artery bypass graft

This bypass is performed for occlusion in distal vessels in patients with severe critical ischaemia who may have accompanying gangrenous lesions in the foot. The graft extends from the femoral artery to either the peroneal or tibial artery in the leg or foot. Distal bypass surgery can be a lengthy and clinically demanding procedure that may also require surgical debridement of gangrenous foot lesions at the end of the arterial reconstruction.

Extra-anatomical bypass graft

Extra-anatomical grafts may be considered for patients who are too unfit for major abdominal surgery and are at risk of limb amputation for critical ischaemia. These synthetic grafts are routed extraperitoneally through subcutaneous tissue to bypass the diseased vessel. The axillary and femoral arteries lie close to the skin surface, making the procedure more rapid and straightforward than more invasive bypassing. Although this type of bypass is less traumatic for patients, the patency rates are much lower than for aorto-iliac reconstructions (Beard, 2000).

Axillo-bifemoral graft

This graft is performed for aorto-iliac occlusion.

Femoro-femoral crossover graft

This graft is performed for iliac artery occlusion.

Preparation of the patient for bypass surgery

Thorough multidisciplinary assessment of the patient is required. The aim of surgery with critical leg ischaemia should be a pain-free patient with a functioning limb. Primary amputation may need considering as an option if there is severe tissue necrosis which prevents weight bearing of the foot, fixed flexion deformity of the limb, or in very frail patients with severe medical problems who could not withstand a lengthy anaesthetic. Acquiring informed consent will require lengthy discussion with the patient and relatives, taking into consideration all these factors.

The patient should be fully informed of the bypass technique and the nurse will need to explain all pre- and postoperative care requirements. Due to the complexity of bypass surgery, the use of diagrams as a teaching aid may be useful for explaining the position of the intended grafts.

• Venous mapping using ultrasound technique is undertaken to determine suitability of the patient’s saphenous vein as bypass material.

• Psychological support for the patient and their relatives is essential (see Ch. 4). Patients with critical limb ischaemia often experience severe pain at rest, impaired mobility, and loss of independence and control. Patients may have concerns about the progression of the disease and may fear the risk of amputation (Treat-Jacobson et al, 2002).

• Relief of ischaemic rest pain by adequate analgesics will be necessary. Pain control should be a priority of care for patients awaiting revascularization to restore blood flow (Ward, 2001). Pain should be regularly assessed and analgesics administered using the WHO (1986) guidelines for pain control: by the mouth, by the clock and by the ladder. Following the ladder of analgesic choice, an oral opioid such as morphine will need to be administered 2–4 hourly, with extra doses given as required for breakthrough pain. Regular aperients will also need to be commenced to prevent constipation. Drowsiness can occur in frail patients, leading to dehydration and malnutrition.

• Nutritional status should be reviewed preoperatively, as a patient with severe ischaemia may be in a malnourished state due to lack of mobility, excessive smoking, severe pain and poor diabetes control. High protein sip feeds should be regularly offered and a dietitian referral made if necessary. Blood glucose levels should be optimized preoperatively in diabetics.

• Reassessment of skin, particularly the heels and sacrum, should be undertaken regularly, and appropriate pressure-relieving mattresses provided (NICE, 2005). The size, location and condition of any ulcerated lesions should be clearly documented.

• The weight of bed linen should be kept off limbs by the use of a bed-cradle, and extreme care taken to avoid accidental trauma to the ischaemic limbs. Unlike venous leg ulcers, patients with arterial leg ulceration should not have compression bandaging applied, as this will cause further impairment to the blood supply (RCN, 2006).

• Infection control measures are essential preoperatively. A culture swab should be obtained from any ulcerated lesions, and appropriate antibiotic therapy given if required, to minimize the risk of graft infection postoperatively, as this can pose a catastrophic risk to the patient. Many vascular patients have prolonged hospital stays prior to surgery, which will increase their risk of surgical site infections (SSIs). Patients should therefore be routinely screened for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and nursed in a low-risk area of the ward wherever possible. Prophylactic intravenous antibiotics are administered immediately prior to surgery, to prevent graft infection. Antiseptic showers/baths are recommended to help reduce skin microbes preoperatively.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access